Even though studies have consistently demonstrated racial-ethnic disparities in access to and quality of mental health care in the United States, findings about changes in such disparities are mixed. One study found that disparities between whites and Latinos in the use of any mental health care grew from 1993 to 2002 (

1), consistent with another study that found increasing racial-ethnic disparities from 2000–2001 to 2003–2004 (

2). However, another study found that disparities between whites and blacks in the use of mental health care in a primary care setting decreased from 1980–1983 to 1993–1996 (

3). Another study found decreasing racial-ethnic disparities in the use of mental health care in a psychiatric setting from 1995 to 2005 but persisting disparities in a primary care setting (

4).

This study assessed changes in racial-ethnic disparities in care between 1990–1992 and 2001–2003 among people with a 12-month mood or anxiety disorder. Data were from two large nationally representative surveys, the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) and the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Changes in disparities were assessed in the use of any mental health care (by health care sector and in total) and in the use of minimally adequate mental health care (in total only) for non-Latino whites compared with non-Latino blacks and Latinos. This study differs from previous studies that assessed changes in racial-ethnic disparities in mental health care because it is the first to use the NCS and NCS-R to examine changes in these disparities among people who were diagnosed as having a mood or anxiety disorder. In addition, it is the first study to assess changes in disparities in the use of minimally adequate mental health care.

Results

At time 1 (1990–1992), the rates of mood or anxiety disorder were similar for whites (22.9%), blacks (22.4%), and Latinos (25.1%). At time 2 (2001–2003), whites (24.9%) had a significantly higher rate than blacks (20.3%, p=.018) but a rate similar to that for Latinos (21.8%). Between time 1 and time 2, disorder rates increased significantly for whites (p=.040) but not for blacks and Latinos (p=.376 and p=.180, respectively).

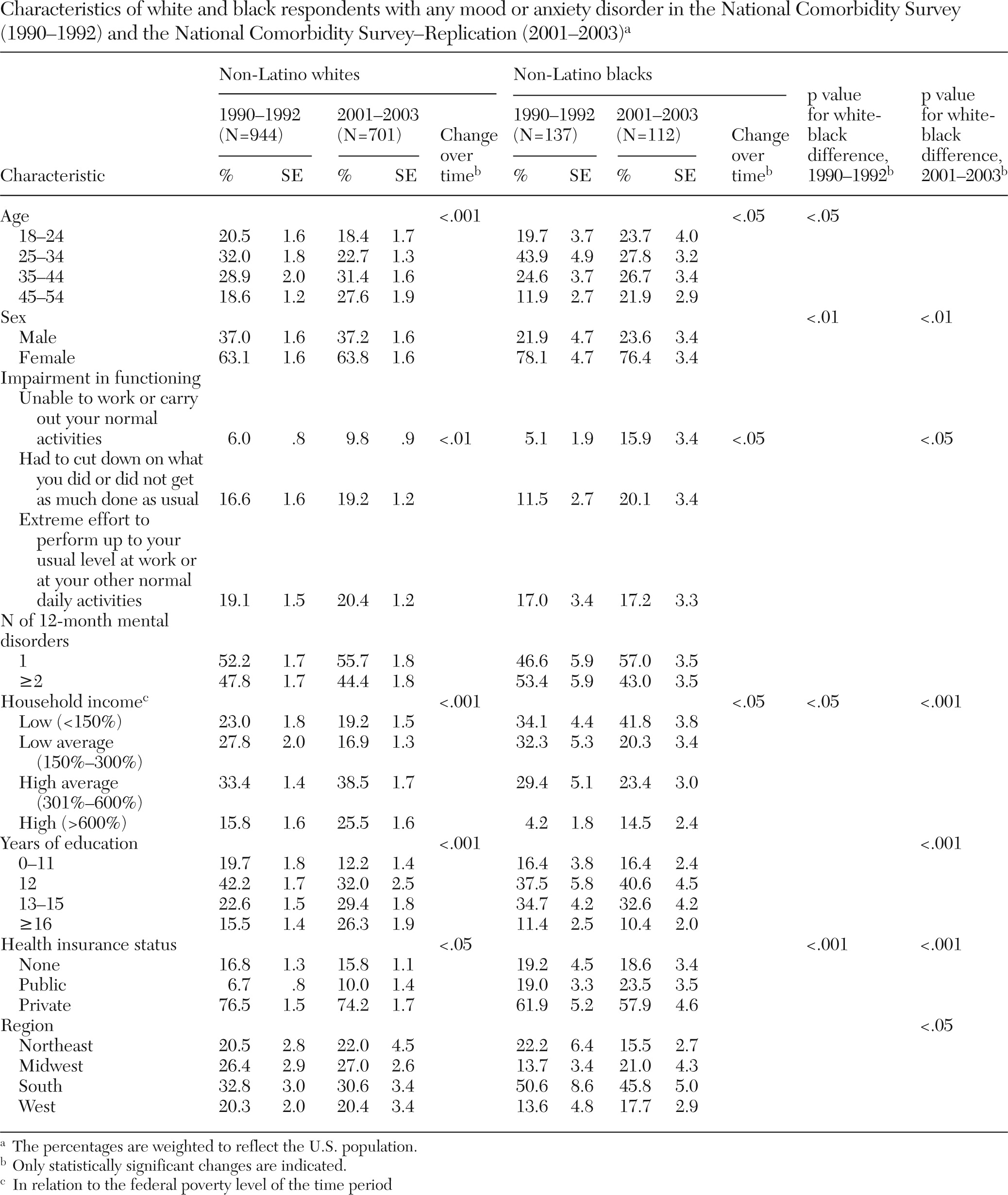

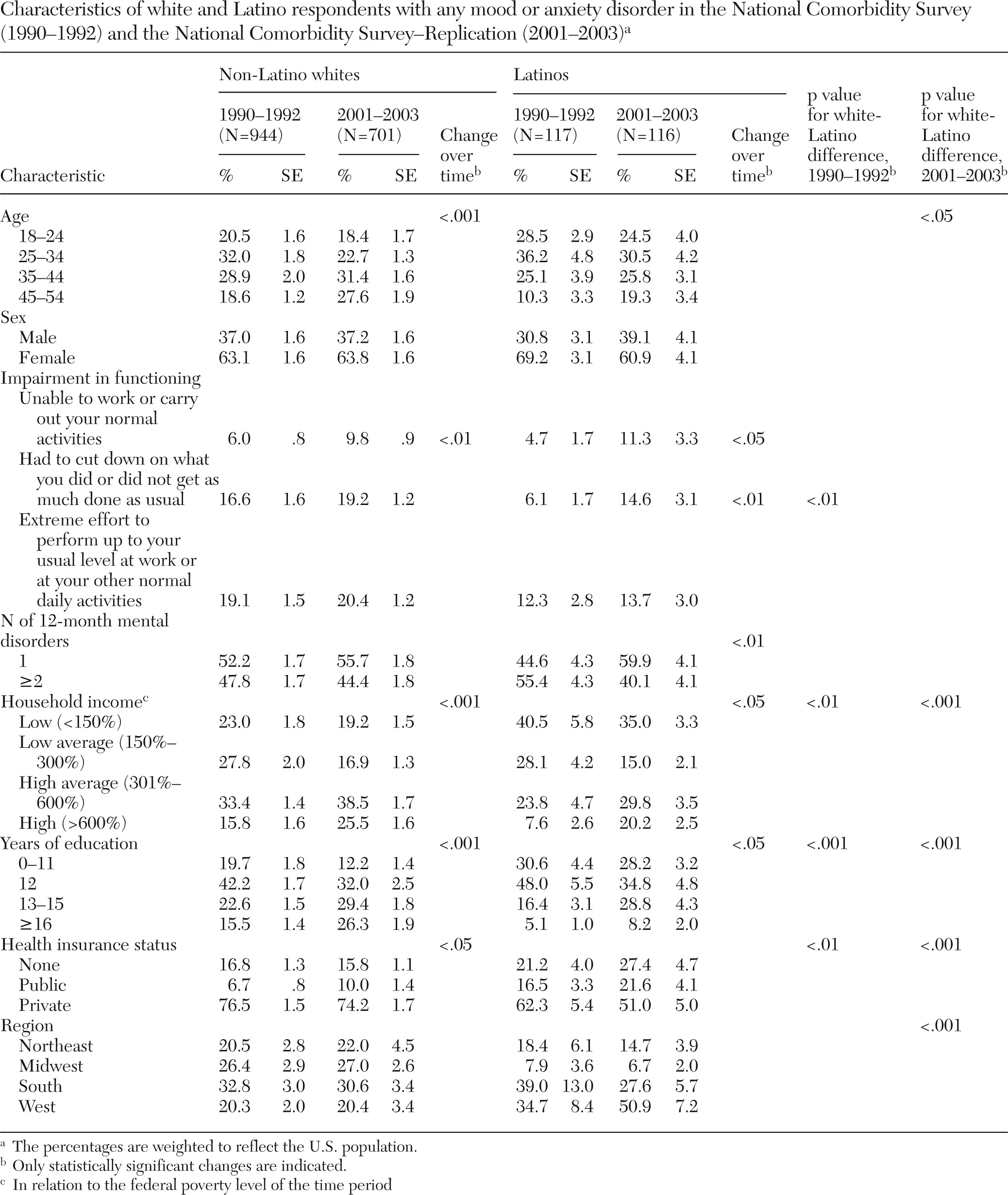

Tables 1 and

2 present data on characteristics of whites and blacks and whites and Latinos, respectively.

At time 1, the adjusted rates of receipt of any mental health care were similar for blacks (19.8%), Latinos (17.0%), and whites (18.8%). At time 2, the rate was significantly higher for whites (36.3%) than for blacks (23.1%, p<.001) and Latinos (25.3%, p<.001). Disparities between whites and blacks in the use of any mental health care increased significantly over time, by 14.2 percentage points (p=.008, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.66–24.67). Disparities between whites and Latinos increased significantly, by 9.2 percentage points (p=.029, CI=.96–17.45).

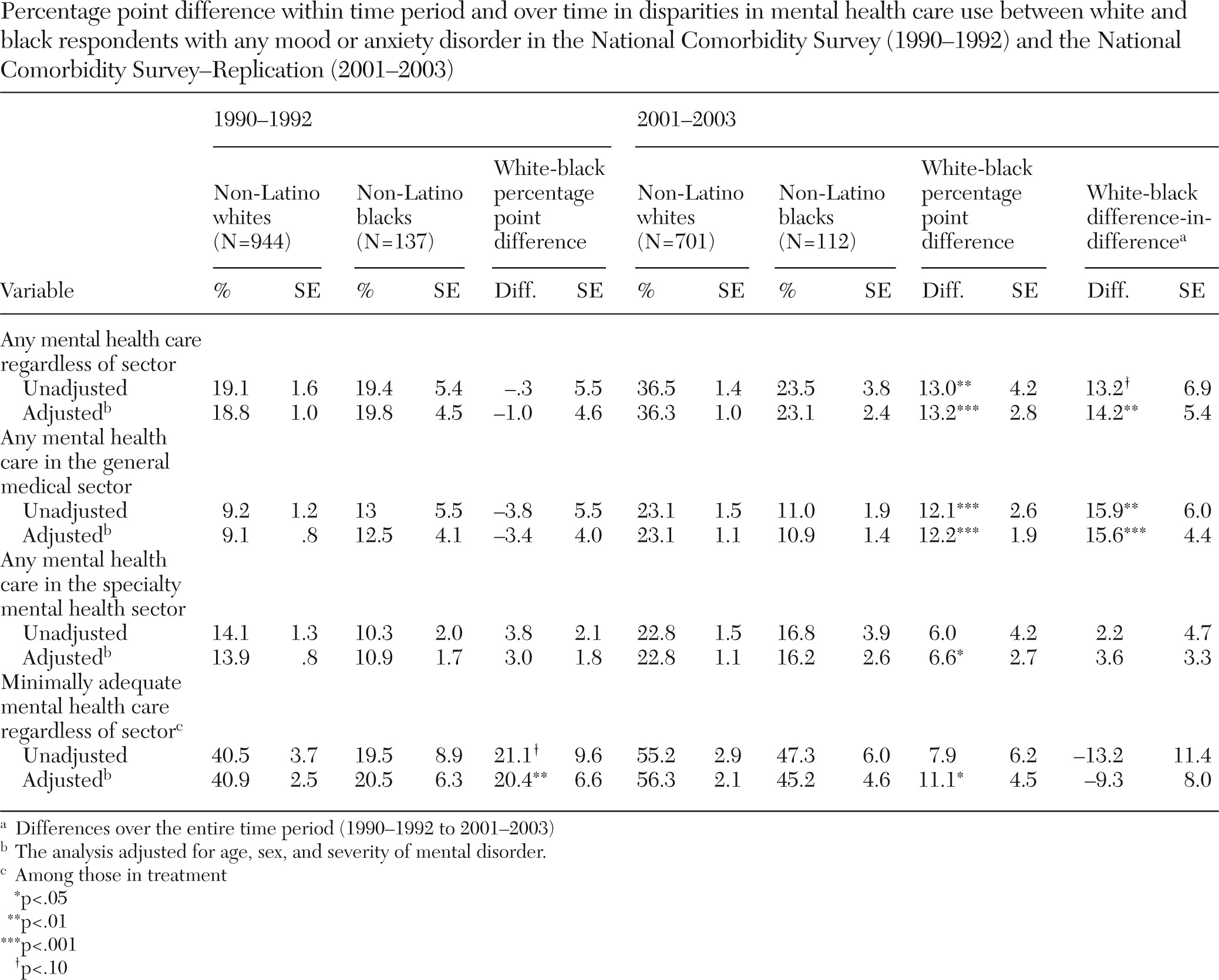

In adjusted analyses, for minimally adequate mental health care at time 1, the rate for whites (40.9%) was significantly higher than the rate for blacks (20.5%, p=.002) but similar to the rate for Latinos (44.1%). At time 2, the rate for whites (56.3%) was significantly higher than the rate for blacks (45.2%, p=.014) but again similar to the rate for Latinos (56.4%) (

Tables 3 and

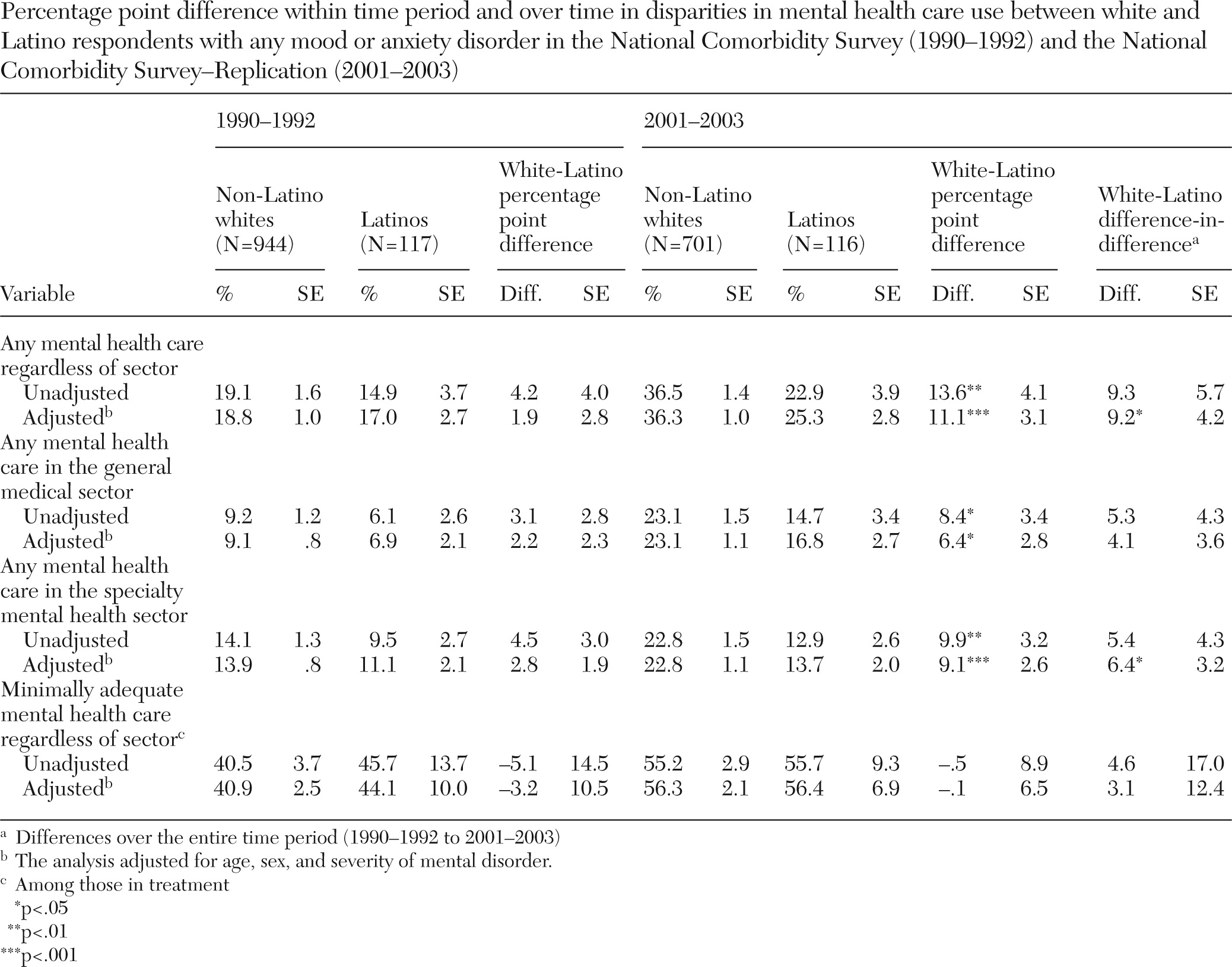

4). Despite the differential increase in the black and white rates, the change in magnitude of the white-black disparity over time was not statistically significant. When the unadjusted rates of medication use among persons in treatment were further examined, a significant white-black difference was found in use of antidepressants at time 1 (whites, 47%; blacks, 20%, p=.004) and a marginal difference was found at time 2 (whites, 66%; blacks, 54%, p=.052); but no significant differences were found between whites and Latinos. No significant white-black and white-Latino differences in the use of antianxiety medications were found for either time period.

In adjusted analyses, at time 1 the rate of use of any mental health care in the general medical sector did not differ significantly for whites (9.1%), blacks (12.5%), and Latinos (6.9%). At time 2, the rate was significantly lower for blacks (10.9%, p<.001) and Latinos (16.8%, p=.021) than for whites (23.1%). The magnitude of the white-black disparity increased significantly over time by 15.6 percentage points (p<.001, CI=6.85–24.29). Although white-Latino disparities emerged at time 2, the change in the white-Latino disparity over time was not statistically significant.

At time 1, the rate of receipt of any mental health care in the specialty mental health sector was similar among whites (13.9%), blacks (10.9%), and Latinos (11.1%). At time 2, the rate was significantly lower for blacks (16.2%, p=.016) and Latinos (13.7%, p<.001) compared with whites (22.8%). The change in the white-black disparity over time was not statistically significant. The change in the white-Latino disparity increased significantly by 6.4 percentage points (p=.048, CI=.06–12.65).

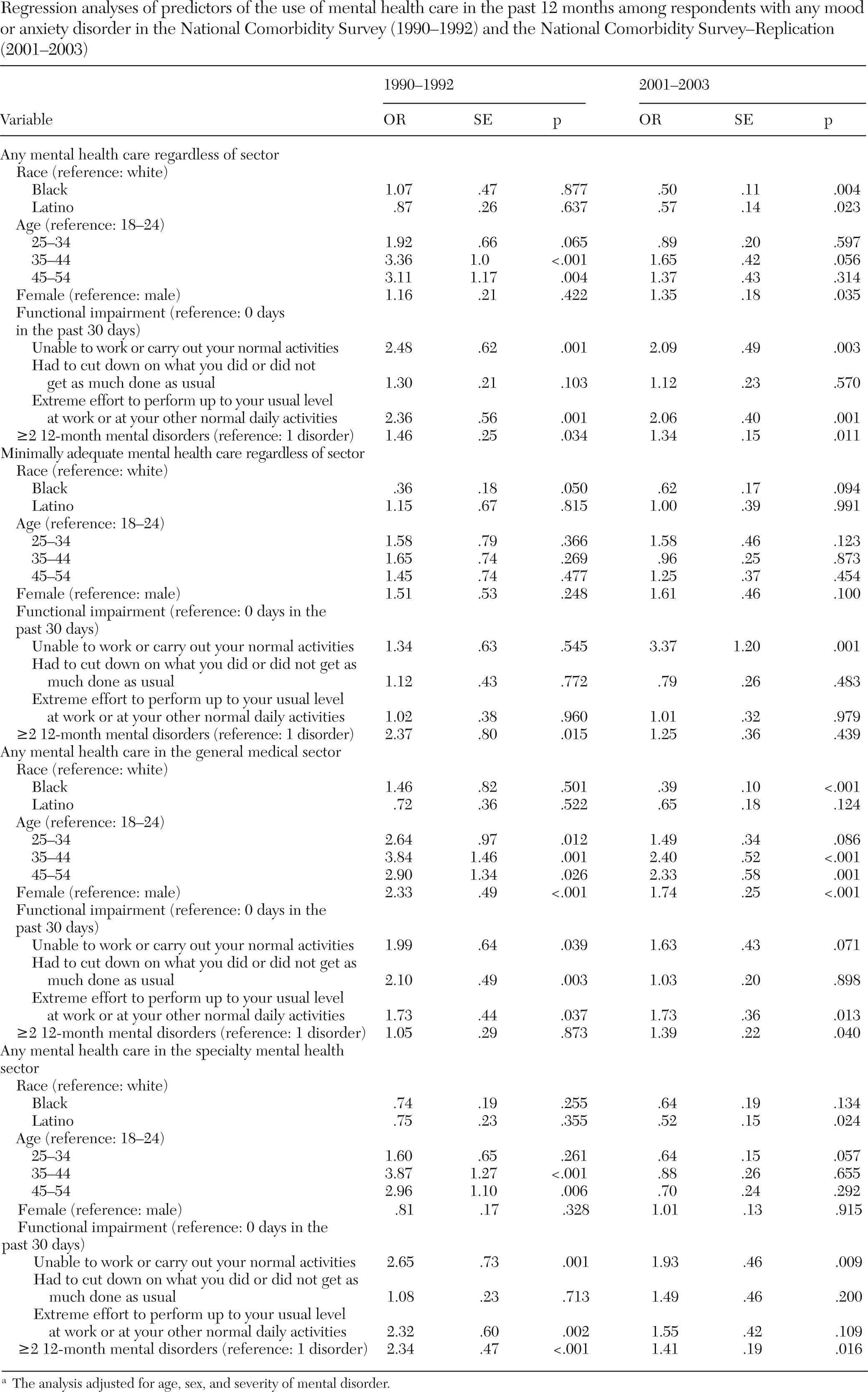

Odds ratios for the results described above are presented in

Table 5.

Table 3 presents data on rates of mental health care use for whites and blacks and respective difference-in-difference estimates.

Table 4 presents these data for whites and Latinos. [Figures depicting the change in differences for whites and blacks and for whites and Latinos are available online as a data supplement to this article].

Discussion

White-black and white-Latino disparities in the use of any mental health care increased between 1990 and 2003, particularly between whites and blacks who used care in the general medical sector and between whites and Latinos who used care in the specialty mental health sector. Disparities persisted between whites and blacks in the use of minimally adequate mental health care. No disparities were detected between whites and Latinos in the use of minimally adequate care for either time period. Improved access to higher-quality mental health care (

32) along with improved attitudes toward mental health care among all racial-ethnic groups (

33–

35) help to explain the increase in the use of care among all groups, but potential differential access to these services may offer an explanation for the increase in disparities. Studies have found that blacks and Latinos are less likely than whites to have access to high-quality care due in part to limited availability of high-quality providers and treatments in the neighborhoods in which they reside (

1,

36–

38). More research is needed in this area.

One possible explanation for the emergence of white-black and white-Latino disparities in receipt of mental health care in the general medical sector is the increased use of antidepressants among whites compared with blacks and Latinos (

39). One study found that despite a substantial increase in antidepressant use over the past two decades and a broad acceptance of antidepressant treatments in the general medical sector, blacks and Latinos were less likely than whites to use antidepressants (

39). The study also found that the rate of antidepressant use did not increase over time for blacks, which might explain the increased white-black disparity in the use of mental health care in the general medical sector. Other studies have found that blacks and Latinos are more likely than whites to prefer counseling to prescription medication for a mental disorder, which may be attributable to the greater likelihood of members of racial-ethnic minority groups to believe that these medications are ineffective and addictive (

40,

41). Of note, a recent study found little evidence of racial-ethnic disparities in the use of psychotherapy (

42). More research may be warranted on whether changes in racial-ethnic disparities in antidepressant use in the general medical sector help to explain white-black and white-Latino disparities.

The emergence of white-black and white-Latino disparities in the specialty mental health sector could be due to the lack of psychiatrists and psychologists from racial-ethnic minority groups in this sector (

43,

44). In 2005, only 3% of psychiatrists and 2% of psychologists were black and 5% of psychiatrists and 3% of psychologists were Latino (

43–

45). In addition, a recent study found that a group of psychiatrists, most of whom were white, had little or no familiarity with the literature on racial-ethnic disparities in mental health care (

46). Researchers posit that racial-ethnic disparities in the mental health workforce may account for disparities in care “because of the greater need for cultural sensitivity in dealing with mental health issues, extensive issues of trust, and the increasing language barrier between provider and patients” (

47).

Preference for treatment modality may explain the persistence of white-black disparities in the use of minimally adequate care. As noted, there are persistent white-black disparities in the use of antidepressants. One literature review cited a study that found that blacks were more likely than whites to adhere to psychotherapy but less likely to adhere to a medication regimen (

48). Patients who are in treatment regimens that they prefer have a greater level of adherence than those in regimens that they do not prefer (

49,

50).

This study differs in several ways from previous studies examining changes in disparities in mental health care. As the first study to use the NCS and NCS-R data sets to examine changes in disparities in mental health care, this study was able to assess need for mental health care on the basis of mental disorders that were assessed with detailed diagnostics via the CIDI. Other studies used psychiatric distress (

3), self-reported mental health (

2), mental health scores from the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (

2), and diagnoses from the

International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification to assess mental health (

1,

4).

This study is similar to those by Cook and colleagues (

2) and Stockdale and colleagues (

4) in that it used the IOM definition of disparities. It is also similar to the study by Cook and colleagues (

2) in that it is the only other study to control for functional status. However, the measures used in this study, unlike those used by the Cook and colleagues, attributed functional limitations to mental illness and thus controlled more appropriately for the effect of limitations on use of care.

The findings are also similar to those in a NCS-NCS-R trend study that found increased inequalities in treatment (

5). However, that study did not specifically describe how inequalities increased. A nontrend NCS study found that blacks and Latinos were significantly less likely than whites to receive specialty mental health care (

19). That study restricted the sample to respondents with any psychiatric disorder in the previous year, whereas our sample included those with a mood or anxiety disorder. A nontrend NCS-R study found a lower overall rate of treatment among racial-ethnic minority groups (

13). However, that study did not find a significant association between race-ethnicity and adequacy of treatment. Its findings are consistent with the white-Latino finding in this study but not with the white-black finding. The differences in findings may be attributable to that study's not restricting the sample to persons with a mood or anxiety disorder and using a stricter definition of adequacy. A broader definition of adequacy needed to be used in our study because of data limitations on processes of care in the NCS that were not limitations in the NCS-R (

5).

This study had other limitations. Power to detect significant differences between racial-ethnic groups and to detect changes in differences over time was limited because of the small samples for blacks and Latinos in the NCS and the NCS-R. The National Latino and Asian American Study and the National Survey on American Life, sister studies to the NCS-R, oversampled for blacks and Latinos, whereas the NCS-R did not do so. Also, the NCS and NCS-R included only English-speaking respondents. Therefore, the findings are not generalizable to non-English-speaking Latinos and blacks. Also, the NCS and NCS-R did not collect data on treatment preferences.

Finally, the IOM definition does not separate out the contributing effect of socioeconomic and access-related factors (such as health insurance status) to racial-ethnic disparities in care. Instead, the definition permits differences in care between racial-ethnic groups that could be mediated, in part, by differences in these factors associated with race-ethnicity to be a part of the disparity (

2,

21,

24). For example, if blacks and Latinos, on average, have lower incomes than non-Latino whites and income is associated with use of health care, then the effect of racial-ethnic differences in income should be counted as a part of the racial-ethnic disparity in care (

2,

24). Some researchers do not agree that the mediating effect of socioeconomic and access-related factors should be included in estimates of racial-ethnic disparities (

51). Given the contrasting views, we have undertaken a study with NCS and NCS-R data to assess the effect of these factors in changes in racial-ethnic disparities in care.

Despite these limitations, the study has notable clinical and policy implications because it estimated changes in disparities by using two of the largest nationally representative epidemiological and service use surveys. The availability of data in the NCS and NCS-R on the number of mental health visits and medication use allowed examination of how disparities in minimally adequate mental health care changed over time. Other strengths of the study are the availability of self-identified race data, independent assessments of mental health status via detailed diagnostic assessment, and data on the type of treatment provider seen by respondents.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, University of Puerto Rico-Cambridge Health Alliance Research Center of Excellence (grant P60-MD-002261); the MacArthur Foundation; Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; and the Advanced Center for Latino and Mental Health Systems Research, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (grant P50-MH-073469). The author receives funding from a Ruth L. Kirschstein-National Service Research Award postdoctoral traineeship sponsored by NIMH and the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School (T32MH019733-17). The author thanks Thomas McGuire, Ph.D., Margarita Alegría, Ph.D., and Alan Zaslavsky, Ph.D., for helpful comments on the manuscript. The author also thanks Benjamin Cook, Ph.D., and Julia Lin, Ph.D., for help with the analysis.

The author reports no competing interests.