Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common chronic childhood psychiatric disorders, affecting an estimated 5.4 million children (

1). Characterized by hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention (

2,

3), children with ADHD are at higher risk for a range of negative outcomes in adolescence and adulthood, including conduct problems, poor peer relationships, and poor school performance (

4). Fortunately, treatments for ADHD, including behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy, have been shown to be effective (

2,

5–

14).

The development of effective treatments and increased public awareness of the disorder has been accompanied by an increase in the number of children identified as having ADHD and being treated for it (

1,

15–

17). Cross-sectional studies that used national surveys and large administrative data sets have described the interventions received by children with ADHD in community treatment settings (

15–

19) and by schoolchildren with ADHD (

20–

22). One study found that among Medicaid-enrolled youths being treated for ADHD, more than half had received medications alone, slightly more than one-third had received both medication and psychosocial interventions, and less than 10% had received psychosocial interventions alone (

19). Another study documented that over a two-year period, more than one-third of children discontinued use of ADHD medications (

23).

Such studies, however, provided limited information about how the care of children with ADHD is initiated and how it evolves over time. Recent qualitative studies suggested that initial treatment of children with ADHD commonly changes (

24). Understanding and characterizing how initial treatment changes are important to improving care in community settings, both to decrease the number of children abandoning potentially efficacious treatments (

25) and to increase the number of children transitioning to more efficacious treatments.

We used administrative data for Medicaid-enrolled children initiating ADHD treatment to examine factors associated with the initial use of medications or psychosocial interventions for ADHD. We also explored factors associated with how quickly use of these treatments changed or was terminated. Specifically, we considered whether treatment was related to factors such as age, gender, and race-ethnicity that may predispose individuals to use health care and factors related to need, such as comorbidities. These factors are associated with access to medical care, according to Andersen's behavioral model (

26,

27) and have been examined in mental health studies that used administrative data sets (

28,

29).

Methods

Sample

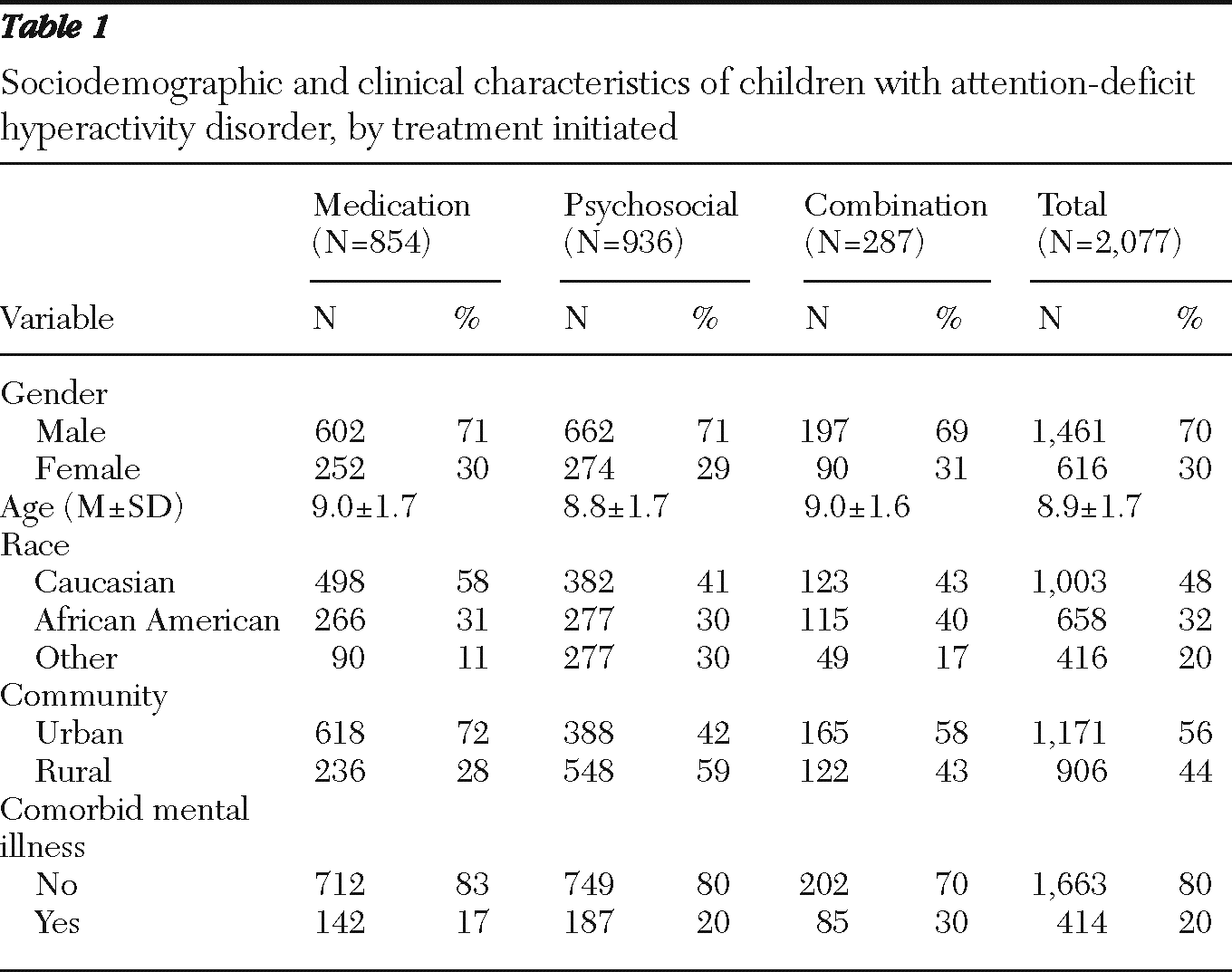

Using administrative state pharmacy data and services claims data from the largest Medicaid-managed behavioral health organization in a large mid-Atlantic state, we identified 2,077 children ages six to 12 who were enrolled in Medicaid and who began treatment for ADHD between October 2006 and December 2007. ADHD treatment initiation was defined as use of ADHD medications—for example, amphetamine, d-amphetamine, atomoxetine, dexmethylphenidate, lisdexamfetamine dimesylate, methamphetamine, and methylphenidate—or as receipt of two mental health specialty treatment services with a diagnosis of ADHD. Children who had received mental health services or psychotropic medications in the 90 days before the first observed ADHD treatment were excluded.

Specialty mental health services included individual, family, and group outpatient therapies (median=one session per week) as well as intensive community-based services such as wraparound services (median=2.3 sessions per week). They excluded nonclinical and nontreatment services such as case management and evaluations. Intensive community-based services are designed to be flexible and could be provided at the child's home or school or in other nonclinical settings, depending on the clinical needs of the child. Consistent with prior research that used administrative data (

30), nonpsychiatric physicians, commonly referred to as primary care physicians, were presumed to prescribe ADHD medication to children who were receiving no specialty mental health care. We selected the first ADHD treatment episode for children with multiple episodes and excluded children with an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis because of their unique treatment needs and service utilization patterns. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt.

Outcome and predictor variables

We defined the period from the initiation of treatment to the first treatment transition as the first-treatment episode, calculated from the initiation of ADHD treatment to either the first transition from initial treatment or to the end of the observation period if the patient did not change initial treatment. Interventions that were received during the first two weeks of the episode were used to categorize the initial type of ADHD treatment. Children who were prescribed medications by a primary care physician but who received no psychosocial interventions were categorized as receiving medication. Children who attended specialty mental health psychosocial intervention sessions and who received no medications were categorized as receiving psychosocial interventions. Children who received a combination of specialty mental health psychosocial interventions and medication were categorized as receiving combination treatment.

A treatment transition occurred when the patient terminated treatment or switched or added a treatment modality. For example, a patient who received medication without psychosocial interventions might add psychosocial interventions, switch to a psychosocial intervention-only regimen, or drop out of treatment. A treatment was considered terminated if there was a 90-day gap in care.

Sociodemographic variables, such as age, gender, and race-ethnicity, were obtained from state files. Race-ethnicity was categorized as Caucasian, African American, or other. Individuals were identified as having been diagnosed with a comorbid mental disorder if they had at least two claims for an anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, conduct or oppositional defiant disorder, or major depression in the 90 days before or after initiating ADHD treatment. Similar to other studies of Medicaid-enrolled individuals (

31,

32), this study categorized children as living in an urban area if their county of residence had a population density greater than 1,000 individuals per square mile.

Data analysis

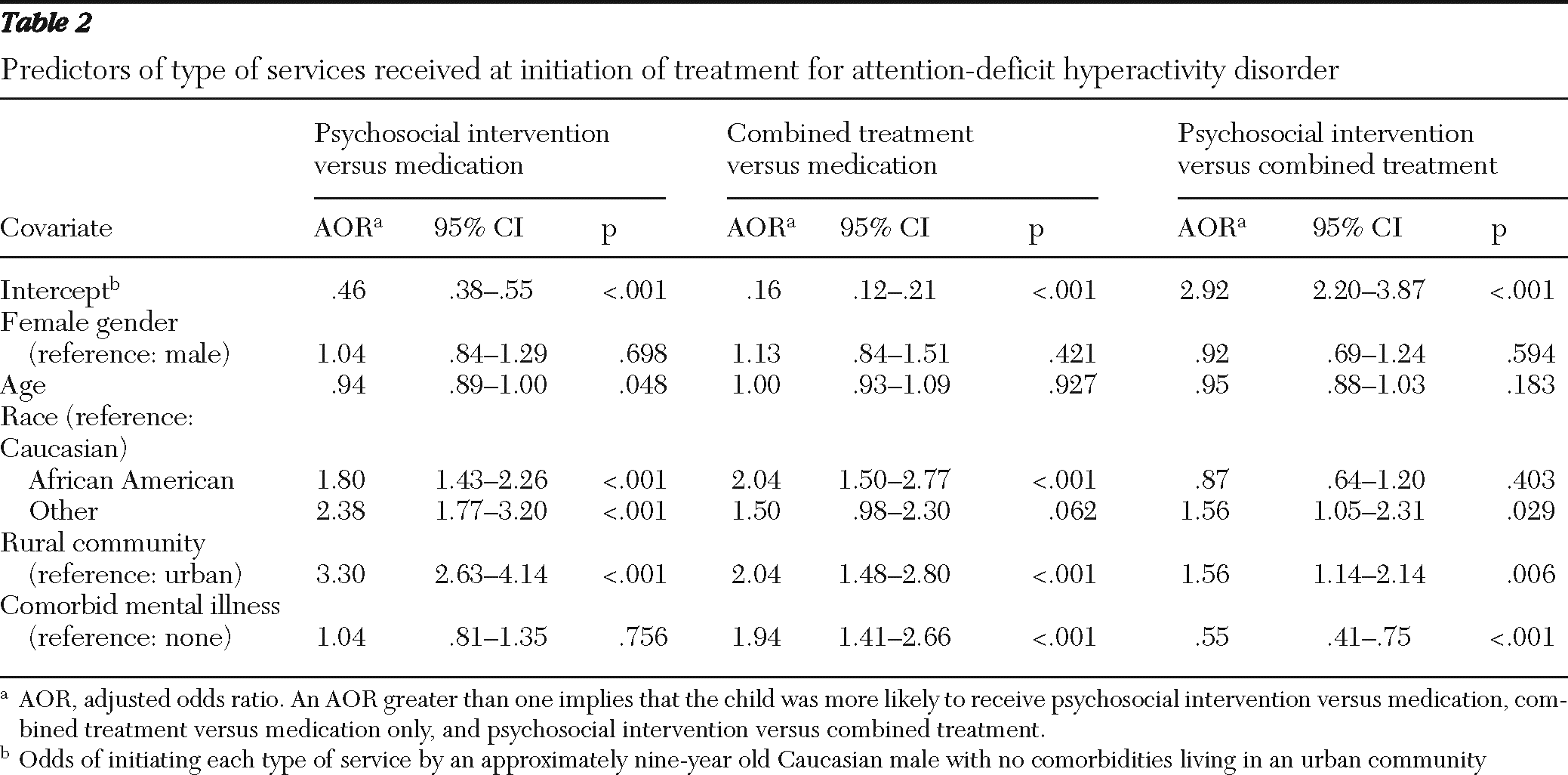

We calculated descriptive statistics for categorical and continuous predictor variables. Multinomial logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with the likelihood of initially receiving psychosocial interventions versus medication; combination treatment versus medication only; and combination treatment versus psychosocial interventions only. We present adjusted odds ratios.

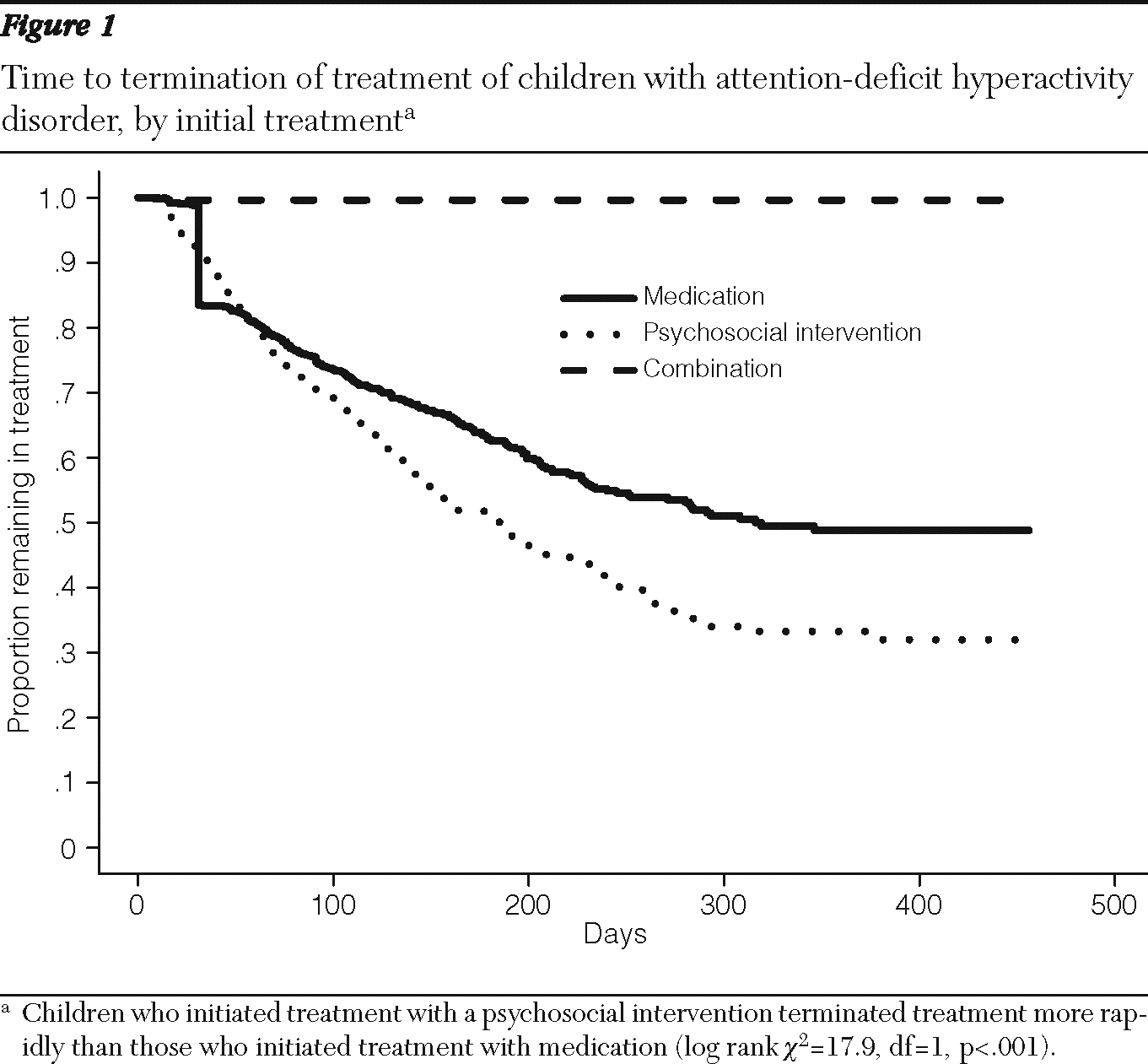

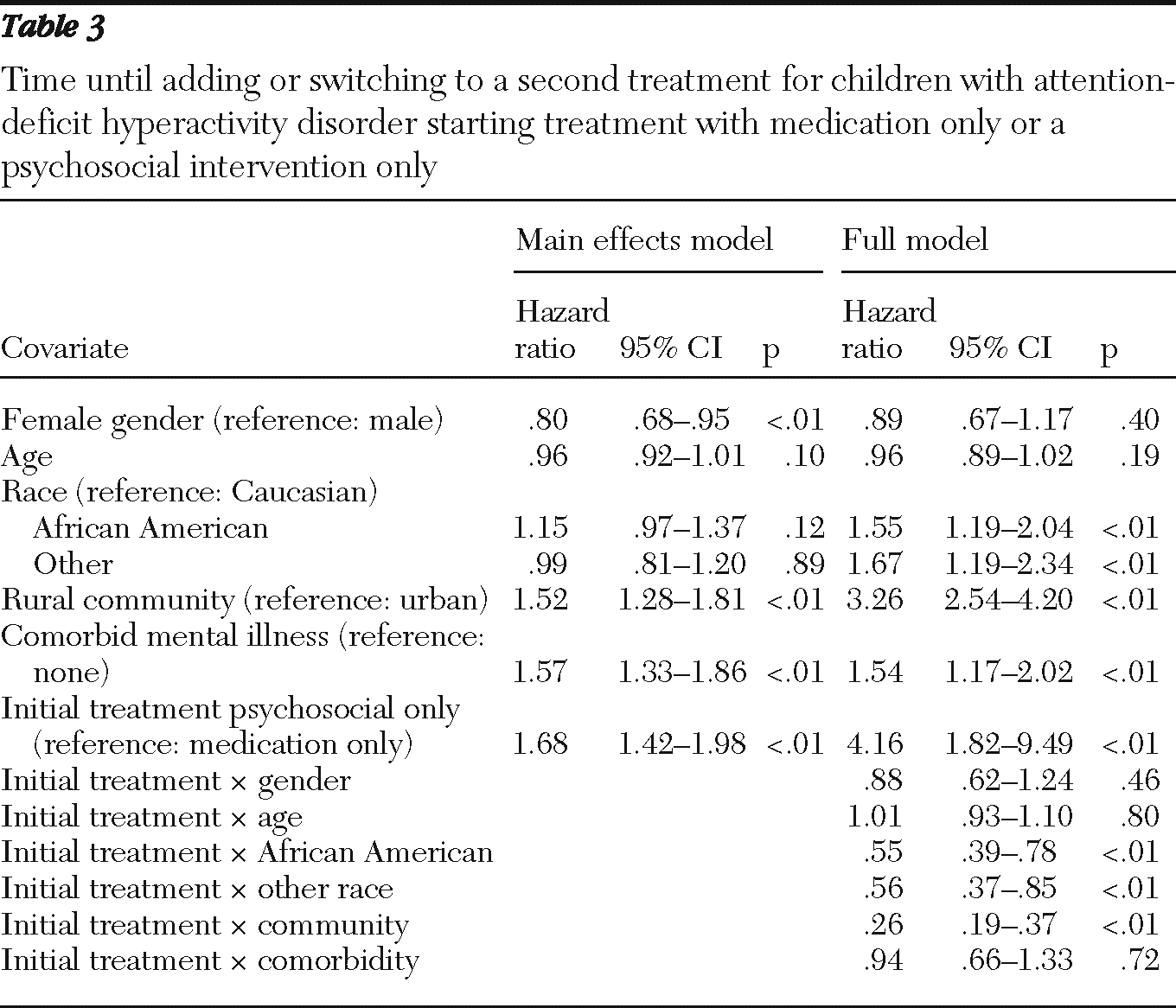

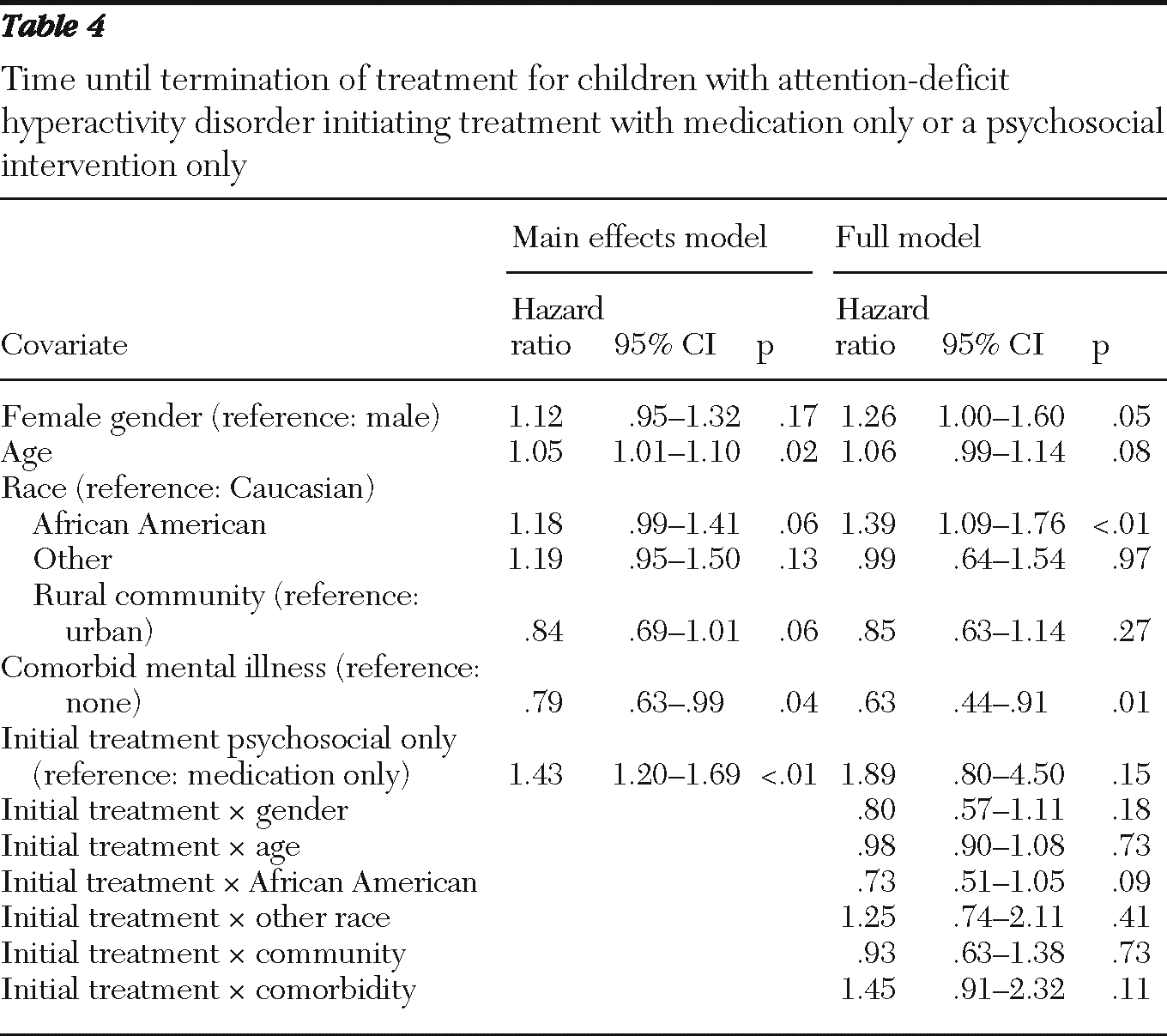

We used Kaplan-Meier survival curves to display the distribution of time until children drop out of treatment, by initial treatment. The log-rank test was used to test for differences in survival curves. Using a Cox proportional hazard model, we investigated the effect of covariates on the time to adding or switching to another treatment modality and the effect of covariates on time to treatment dropout. To assess the sensitivity of the findings when the end of the treatment episode was defined as a gap in care of 90 days, we repeated the analyses by using a 120-day gap in care to identify the end of treatment. We found no substantial change in results. SAS, version 9.2 for Windows, was used for data management and analysis.

Discussion

This examination of Medicaid-enrolled children initiating ADHD treatment found that a vast majority of children began treatment with either a psychosocial intervention alone or medication alone. After initiation of treatment, however, a substantial number either switched to or added another treatment modality.

Children who received both medication and a psychosocial intervention stayed in treatment the longest, and those who received a psychosocial intervention alone dropped out soonest. Although we are unaware of empirical studies examining the course of children's initial ADHD treatment in community settings, our findings are consistent with reports that parents explore both pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions for children with ADHD (

24) and suggest that families may feel dissatisfied with the effectiveness of initial treatments.

Studies have documented both the large number of children receiving only stimulants for ADHD (

34) and the limited access to mental health specialty care for patients of pediatricians (

35,

36). Unexpectedly, we found that the proportion of children initiating treatment with a psychosocial intervention alone from mental health specialty providers was nearly the same as the proportion receiving medications alone. However, although only 14% of children initiated treatment with a combination of medication and a psychosocial intervention by a specialty mental health provider, by the end of the first treatment episode, 34% received such care. On one hand this finding was encouraging because according to many practice guidelines, combined care is considered optimal, particularly for children with comorbidities (

9,

10). On the other hand, a minority percentage of children in the sample received optimal care.

Psychosocial interventions alone were more commonly initiated than combined treatment, perhaps because parents preferred such interventions for children with ADHD (

37,

38). Greater access among Medicaid-enrolled populations to mental health specialty care (

39) and the greater severity of emotional and behavioral problems of Medicaid-enrolled children (

40) may also have contributed to the use of psychosocial interventions alone as initial treatments. Further research is needed to better understand factors influencing decisions about initial ADHD treatment and how the initial treatment response subsequently affects ongoing preferences, course of treatment, and clinical outcomes.

We found that many children who initially received a single treatment modality, either medications or psychosocial interventions, added the other treatment relatively quickly. Such a pattern could reflect mental health clinic policies, such as a requirement that children and families begin treatment with a therapist before receiving a psychiatric evaluation. In addition, differences in access to services may allow some children to receive medications from a primary care clinician while they wait for specialty mental health care.

A desire for rapid symptom improvement may also contribute, given that medications are added to treatment more quickly than are psychosocial interventions. Psychosocial interventions' benefits often accrue after a number of visits and require that parents invest more effort and time (

10) than are required to provide medications. Changes in treatment often occur naturally as a result of the child's treatment response and as the preferences of the child and family evolve (

24). Further studies are needed to better understand the extent that child and family preferences and clinical needs, rather than limited access to particular services or provider organization policies, dictate the evolution of appropriate and effective treatments during the treatment episode.

Our findings suggest that African-American children with ADHD may be less likely to use medications. They were more likely to initiate ADHD treatment with psychosocial interventions alone and were more likely to transition to psychosocial interventions after initiating treatment with medications. This finding is consistent with studies that have examined decision making by parents from racial and ethnic minority groups about initiating ADHD treatment. Some studies have found greater reluctance by members of minority racial and ethnic groups to initiate treatment with medications and to accept the diagnosis of ADHD (

24,

41,

42). Another study showed that African-American children with ADHD are less likely to receive special education services (

22). In addition, a general population study found that African Americans were more likely than whites to prefer counseling (

43).

Information about which of Andersen's predisposing, enabling, and need factors are associated with differences in treatment initiation and subsequent care can help target efforts to ensure that parents can make informed decisions about the best treatment options for their child and help minimize treatment disparities.

The finding that approximately one-third of children who initiated treatment for ADHD discontinued treatment within six months is concerning, but it is consistent with the lack of treatment continuity documented by others (

44). Fortunately, experts have developed effective interventions to increase engagement of families initiating treatment for children's emotional and behavioral disorders (

45). Our findings, however, are limited to the first treatment episode, and longitudinal studies are needed to better understand how treatment patterns continue to change and differentially affect clinical and functional outcomes.

The results of this study must be viewed in the context of its limitations. We used administrative data that lack rich clinical, social, and environmental information, such as severity of illness, that likely explain a significant amount of the variation in patterns of ADHD care. We had no information regarding children's prior treatment episodes nor about support, such as from a pastoral or school counselor or in a special education classroom, that the child may have received outside the mental health system. We did not have prescribing physician information, and were unable to examine questions associated with physician specialty. We had no information on the quality or clinical appropriateness of services—factors that are related to children's clinical outcomes. We also did not have information about children's Medicaid-eligibility category, which has been associated with variations in children's use of psychotropic medication (

46).

The geographic regions we examined have a relatively robust specialty mental health system and generous Medicaid mental health benefits. All Medicaid-enrolled children are covered by a single managed behavioral health care organization, and there are minimal mental health services funded by a block grant. We do not know how our findings generalize to regions with different Medicaid mental health polices or benefits, to commercially insured children or other populations, or to areas with greater or fewer mental health providers. Finally, the data did not permit us to make causal inferences regarding the associations we observed.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this examination of treatment received by Medicaid-enrolled children initiating treatment for ADHD provides important information that cannot be feasibly obtained from other data sources (

47). We are unaware of other empirical studies that demonstrate the relatively rapid changes in use of treatment modalities for children beginning ADHD treatment in real-world treatment settings. Many of the rapid changes we document involved children transitioning from psychosocial interventions delivered in community settings, which are often thought to be relatively ineffective (

48–

51), to potentially more effective interventions incorporating appropriate medications. This pattern has potential to be encouraging, given that the use of such medications in the treatment of ADHD is consistent with many practice parameters and guidelines.

At the same time, given the large number of children who initiated and continued to receive psychosocial interventions as part of their treatment for ADHD, our findings are supportive of the calls to find ways to increase the use of evidence-based psychosocial interventions and other effective treatment components in the treatment in community settings of children with disruptive disorders such as ADHD (

52,

53).

Equally important is developing a better understanding of what underlies the patterns of care we observe. Optimally, the treatment modalities we observe when a child initiates treatment for ADHD result from the joint decisions of clinicians and informed parents. They could, however, also arise from difficulties in treatment access or misperceptions regarding advantages and disadvantages of different types of treatment modalities. Further research is needed to better understand what underlies the patterns of evolving care that this study has revealed so that all families seeking care for children with ADHD may receive preferred and effective treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support for this study was provided by a Community Care Behavioral Health/WPIC Academic Partnership Award. The authors thank Jennifer Wisdom, Ph.D., Kimberly Hoagwood, Ph.D., and Abigail Schlesinger, M.D., for feedback and comments on the manuscript and Emily Magee, M.P.H., Karen Celedonia, M.P.H., and Amanda Ayers, M.S.P.H., for research assistance.

The authors report no competing interests.