Poor adherence to antipsychotics has been commonly observed among patients with schizophrenia (

1). Poor adherence has been demonstrated to be the best predictor of relapse (

2), as well as a high-risk factor for rehospitalization (

3) and suicide (

4). Second-generation antipsychotics were developed with the hope of broadening efficacy and minimizing side effects, especially extrapyramidal symptoms, which are often associated with the use of first-generation antipsychotics. Consequently, the second-generation medications were also expected to lead to better adherence. Although some research supports this claim (

5), other studies do not (

6,

7).

Patterns of medication prescriptions and adherence are often classified into adherence (or refill), switch, and discontinuation. Studies have shown that second-generation antipsychotics may be associated with a longer duration of adherence (

8,

9) and with less likelihood of switching than found with first-generation antipsychotics (

10). Moreover, Dolder and colleagues (

5) observed a higher rate of adherence among patients receiving second-generation antipsychotics compared with those receiving first-generation antipsychotics.

Adherence to antipsychotics is relatively poor among persons experiencing their first episode of psychosis. One-third of patients with schizophrenia have been estimated to be nonadherent to medication within six months of their first psychotic episode (

6). There are no published reports of antipsychotic adherence in newly diagnosed schizophrenia among Asians, and any pattern for this population remains unclear. In this study, we used the national health insurance research database (NHIRD) in Taiwan to investigate adherence patterns with first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics during patients' first month of treatment for schizophrenia, which is a critical period for treatment engagement.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study based on a large computerized data set, Taiwan's NHIRD (

www.nhri.org.tw/nhird/date_01.htm). The NHIRD has collected registry and claims data on outpatient services, inpatient care, dental care, physical therapy, preventive health care, home care, and rehabilitation for chronic mental illnesses. Taiwan's national health insurance (NHI) program provides comprehensive coverage for 99% of the population of 23 million in Taiwan, with a 98% participation rate. This study used one of the subsets derived from the NHIRD database, containing all original claims data from 1997 to 2006. A total of 200,000 individuals (roughly 1% of the total population) were randomly sampled from the NHI registry for beneficiaries registered in 2000; this sample was representative of all individuals included in NHIRD.

In this study, we defined newly treated schizophrenia on the basis of the following criteria: a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code 295.X); first diagnosis between January 1, 1998, and June 30, 2006, and excluding schizophrenia cases diagnosed in 1997; and prescription of either first-generation antipsychotics or second-generation antipsychotics. First-generation antipsychotics included chlorpromazine, chlorprothixene, clopenthixol, clothiapine, droperidol, flupentixol, fluphenazine, haloperidol, loxapine, penfluridol, perphenazine, pimozide, pipotiazine, sulpiride, thioridazine, thiothixene, triflumethazine, trifluoperazine, and zuclopenthixol; second-generation antipsychotics included amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and zotepine.

In general, when schizophrenia patients in Taiwan are first diagnosed, they receive prescriptions for one or two weeks of antipsychotics and arrange for a follow-up appointment with their physician. Therefore, for most of these patients, the second antipsychotic prescription appears in the NHIRD record within one month of the first visit. Accordingly, patients were classified into the following four early adherence patterns within the first month: refill, the patient stays on the same antipsychotic; switch, the patient switches to an antipsychotic that is different from the initial medication; admission, the patient is hospitalized for treatment of schizophrenia; and discontinuation, where no second antipsychotic prescription is identified in the claims data within one month of the first visit. We also reviewed medical claims data for use of antipsychotics at patients' first visits—whether outpatient or inpatient visits—including names of antipsychotic drugs, days' supply, dosage route of administration, and date of prescription collected in the pharmacy prescription database in NHIRD. For patients in the switch category, we identified whether switches occurred within the same group of antipsychotics or different groups of antipsychotics from both outpatient and inpatient medical claims data collected in the pharmacy prescription database in NHIRD.

We used chi square tests to examine the association between choices of initial antipsychotics and patients' age and gender, as well as the specialties of prescribing physicians. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were applied separately to test for differences between antipsychotics first used and early adherence patterns. In particular, we performed three univariate and three multivariate logistic regression analyses to compare refill with discontinuation, switch with discontinuation, and admission with discontinuation. Covariates adjusted in multivariate logistic regression included age, gender, and prescribers' affiliations. A trend test was performed to examine differences in adherence rates for the first six months between initial choices of antipsychotics. All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 13.0.

Results

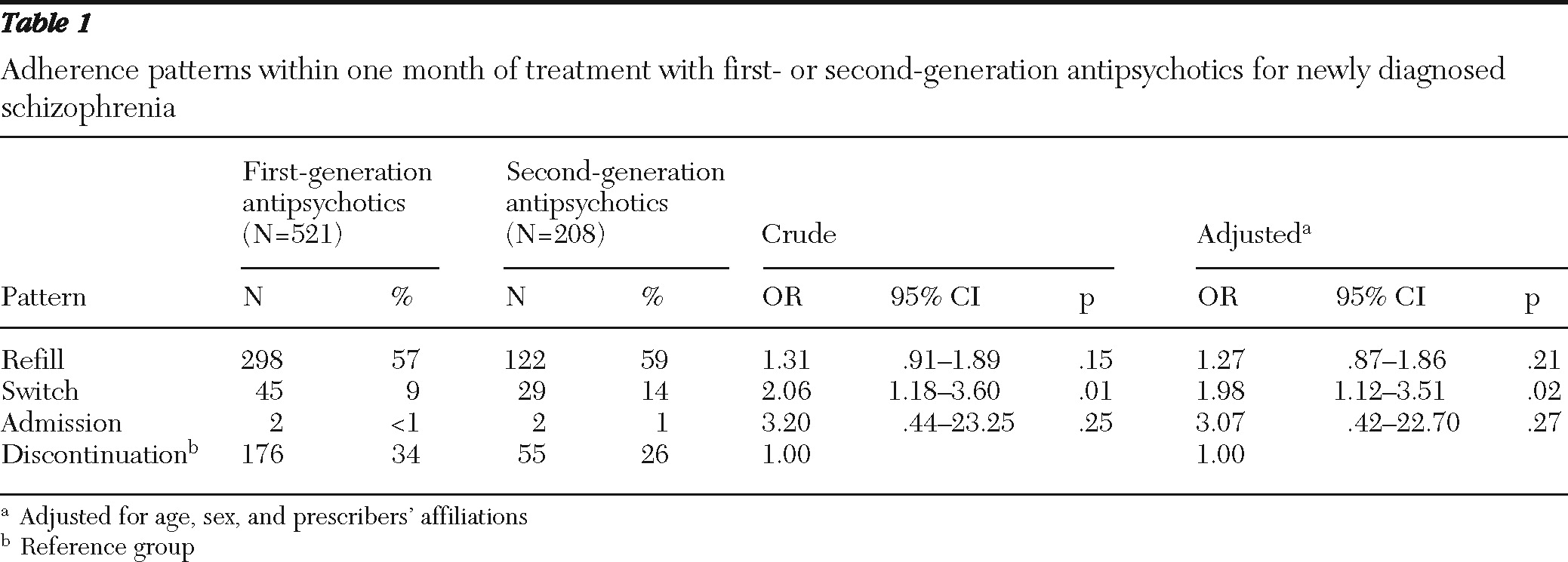

A total of 729 patients with a new diagnosis of schizophrenia were identified from the database. [A table of characteristics of the initial choice of first- and second-generation antipsychotics for newly diagnosed schizophrenia is available online as a data supplement.] A total of 521 (72%) patients were initially treated with first-generation antipsychotics, and 208 (29%) were initially treated with second-generation antipsychotics. When first diagnosed, half of the patients were between 25 and 44 years old (N=357, 49%). More than half of diagnoses were made by psychiatrists in general hospitals (N=430, 59%), followed by psychiatrists in psychiatric hospitals (N=160, 22%) and nonpsychiatrists (N=139, 19%).

Among those initially treated with first-generation antipsychotics, 57% received and refilled the same antipsychotic at their second visits (

Table 1). In comparison, the refill rate for initial treatment with second-generation antipsychotics was 59%, slightly higher than for those initially treated with first-generation antipsychotics. The switch rate was lower among patients initially treated with first-generation antipsychotics than among those prescribed second-generation antipsychotics (9% versus 14%). The discontinuation rate was higher among patients who initially received first-generation antipsychotics than among those who started with second-generation antipsychotics (34% versus 26%). Using the discontinuation group as the reference group, we found that patients who initially received second-generation antipsychotics were nearly twice as likely to switch, a significant difference (p=.02) compared with those who initially received first-generation antipsychotics, even after adjustment for covariates (

Table 1).

In addition, we found better adherence within six months among patients treated first with second-generation antipsychotics compared with first-generation antipsychotics (see figure in online data supplement). After one month, 57% of those starting on first-generation antipsychotics were adherent with the same medication, whereas the rate of adherence was 59% for patients starting on second-generation antipsychotics (

Table 1). After six months, only 17% (N=89) of patients initiated with first-generation antipsychotics and 21% (N=44) of patients initiated with second-generation antipsychotics remained on the same medications. Furthermore, we examined whether the trend in adherence rates over six months differed between patients initiating treatment with first-generation antipsychotics versus second-generation antipsychotics. The trend test showed a between-groups difference of borderline significance (p=.07).

Discussion

Using an insurance claims database, this study aimed to compare the adherence patterns with first-generation versus second-generation antipsychotic medications in newly diagnosed schizophrenia. Our results demonstrated that patients whose treatment began with second-generation antipsychotics were more likely to switch within one month of diagnosis but less likely to discontinue antipsychotics compared with those who began treatment with first-generation antipsychotics.

In comparing our results with those of other studies, some methodological differences should be noted. First, our study sample was based on newly diagnosed and treated schizophrenia. We excluded claims indicating schizophrenia diagnoses or antipsychotic use in the year before the study period. Definitions of diagnosis and antipsychotic usage for our study were similar to those reported by Mirandola and colleagues (

8). Generally, when schizophrenia is first diagnosed, patients may be shocked by their diagnosis and sensitive to and unfamiliar with the side effects of antipsychotic medications. Instability of symptoms may delay establishment of a trusted doctor-patient relationship. All of these factors together may make adherence in these early stages of psychotic illness worse than adherence in chronic schizophrenia. Second, in order to explore early adherence patterns within one month of initial antipsychotic treatment, we defined “initial antipsychotics refilled in the second visit” as “refill,” which might be a narrower definition than was used in other studies. For example, Rijcken and colleagues (

11) defined refill rate as “the number of days that antipsychotics have been dispensed to a patient in a defined period, divided by the total number of days in that time period,” whereas Dolder and colleagues (

5) used cumulative mean gap ratios and compliance refill rates to assess adherence.

Our findings on switching were in accordance with those reported by Rothbard and colleagues (

10). They suggested that patients initially treated with first-generation antipsychotics were less likely to have to switch their medication later. In contrast, another two studies reported that patients starting on second-generation antipsychotics were less likely to switch medications (

12,

13). Among these three studies, two were done in the United States (

10,

12) and one was done in Europe (

13). Our study was the first done in Asia. Whereas the three previous studies followed their study populations for one year, ours compared antipsychotic prescriptions between patients' first and the second visits after they first received a schizophrenia diagnosis and followed patients for one month to determine whether they switched medications. Compared with reports on studies from Western countries, our data suggest that adherence might be more problematic in Taiwan.

There are several possible explanations for poor adherence in Taiwan. First, a previous study reported that high-dosage antipsychotic treatment is not uncommon in East Asian countries (

14). High dosages of antipsychotic drugs may lead to poor adherence because of the adverse effects of these drugs. Second, a study conducted in Vancouver, British Columbia, found that Chinese families had a distinctive way of dealing with family members with mental illness (

15). Outpatient or inpatient treatment from mental health specialists was usually not their first choice. Together, these findings indicate that differences between Asian and non-Asian populations in prescribing patterns, medication tolerance, and cultural attitudes toward illness and medication may explain the poor adherence observed in this study.

Differences in second-generation antipsychotics may exert different effects on adherence. For example, the CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) study (

2) showed that for 74% of study participants, time to treatment discontinuation was significantly longer among patients who received olanzapine compared with those who received quetiapine or risperidone. Similarly, Ren and colleagues (

9) reported better treatment persistence in schizophrenia treated with olanzapine versus risperidone. We did not evaluate the effect of individual antipsychotics on adherence patterns in this study. Further studies are needed to explore adherence patterns with different kinds of antipsychotics in Taiwan.

Similar to other studies using insurance claims databases, this study had a number of limitations. First, a certain proportion of patients included in this study were probably beyond a first episode of schizophrenia because we did not consider patients who received their diagnosis before 1997 and did not seek either inpatient or outpatient medical services in 1997. Similarly, on the basis of our definition of newly treated schizophrenia, this study may have included patients who were newly treated with an antipsychotic or patients who might not have been experiencing their first episode of psychosis. Second, medication records do not directly measure the actual medication intake. Third, because data on efficacy and side effects were not available, we were unable to analyze the relationship between these two factors and early adherence. Finally, a number of other potential confounding factors that might affect adherence such as baseline Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores and education level were not available in the NHIRD, and data therefore were not adjusted for these variables in this study. For these reasons, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Several strengths and unique features of this study are noteworthy. Our study is the first to examine early adherence of patients newly treated for schizophrenia and who were tracked prospectively from when they first entered the medication claims system. Our study was based on national data. As such, it provided a sufficient sample size to address the early adherence issue. In addition, our study is the first in Asia to investigate early adherence to schizophrenia medications. The results of this study provide evidence that poor adherence to antipsychotics is an important problem in newly treated schizophrenia and underscore the importance of developing new therapeutic strategies to solve the early adherence issue.

Conclusions

The study demonstrated that early adherence to antipsychotic treatment for newly diagnosed schizophrenia is alarmingly poor in Taiwan. To improve the treatment outcome of patients newly treated for schizophrenia, the results suggest the urgency in and importance of developing preventive strategies for those at risk of early discontinuation of antipsychotics.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant NSC 94-2314-B-040-040 from the National Science Council. Dr. Tsai is supported in part by grants PH-099-PP-56 and PH-100-PP-14 from the National Health Research Institutes. This study is based in part on data from the national health insurance research database provided by Taiwan's Bureau of National Health Insurance in the Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Bureau of National Health Insurance, the Department of Health, or the National Health Research Institutes.

Dr. Chi-Shin Wu has received speaker's honoraria from Eli Lilly. The other authors report no competing interests.