Late-life mood and anxiety disorders are common and often co-occurring among community-dwelling adults (

1). Although these disorders are treatable (

2–

7), it is estimated that over 50% of older adults symptomatic for a clinical diagnosis do not use mental health services (

8–

10). Yet little is known about why, despite symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders, these older adults typically do not seek services. It is commonly held that poor use is due to stigma associated with mental health care and poor coordination of care (

11); however, these assumptions are often made from community-based samples including older adults who do not have a mental illness (

12). With consideration of the current and projected growth of the older segment of the population and because mood and anxiety disorders are highly associated with poor health outcomes (

13–

17), the impact of untreated late-life mood and anxiety disorders has major public health implications. Thus understanding the factors that influence low use of mental health services by those with greatest need is vital.

Most prior research on mental health service use by older adults with psychiatric diagnoses has been with clinical populations (

18,

19). Because these studies are limited to individuals whose mental disorders become known only in the course of seeking care, nonutilizers are often excluded from study. Although population-based studies are important resources for the examination of use and nonuse, few have clinical measures of mood and anxiety disorders and none that we are aware of have determined key predictors among those with psychiatric conditions (

8–

10,

20–

26). In contrast, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) data examined in this study are nationally representative, with clinically based measures of mood and anxiety disorders as well as a broad range of potential predictors of nonuse.

The primary purpose of our study was to determine the prevalence and key factors associated with not using mental health services in a national sample of older Americans meeting criteria for DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders. This study contributes to understanding unmet need and barriers to care in the United States among the most affected older adults.

Discussion

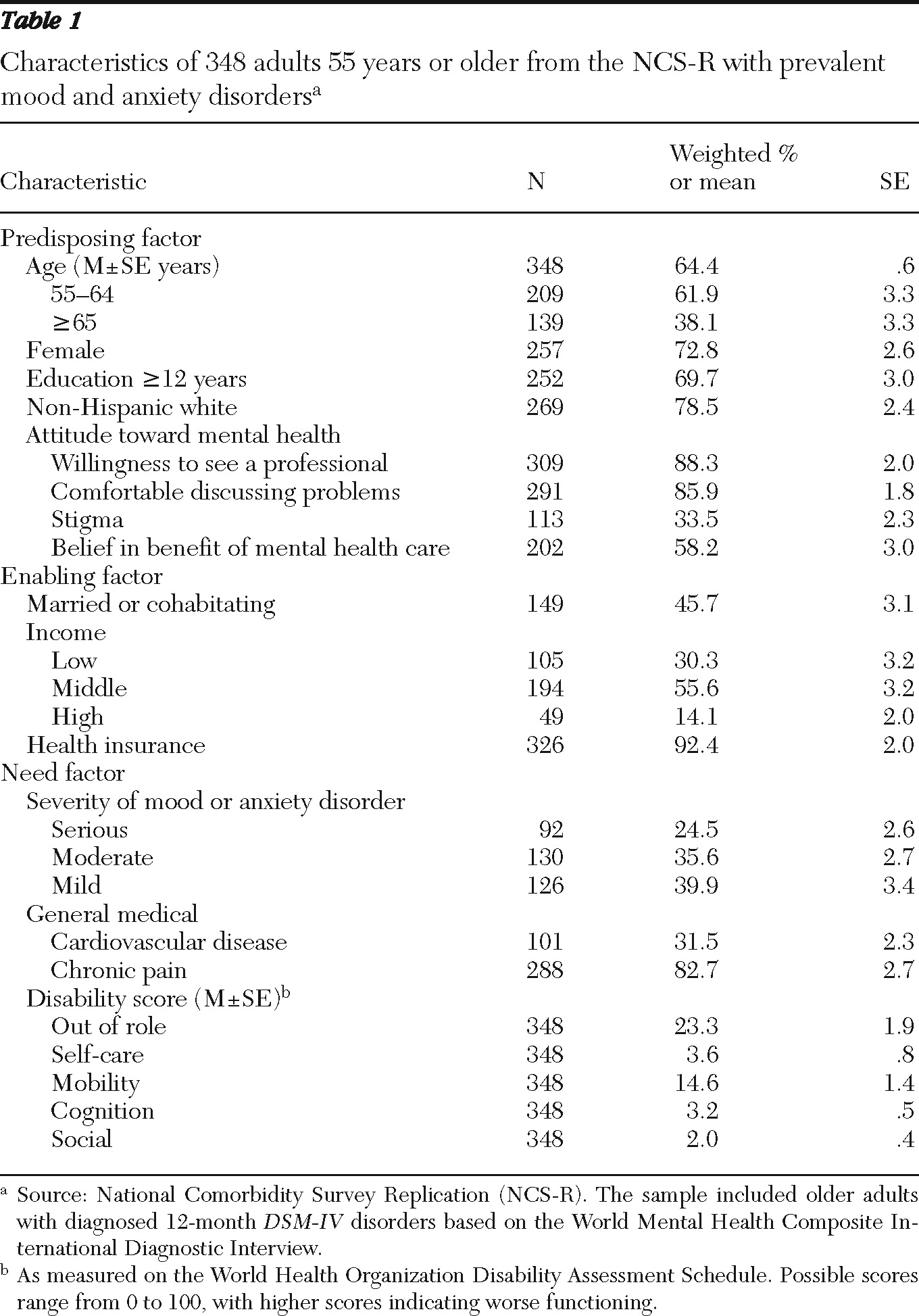

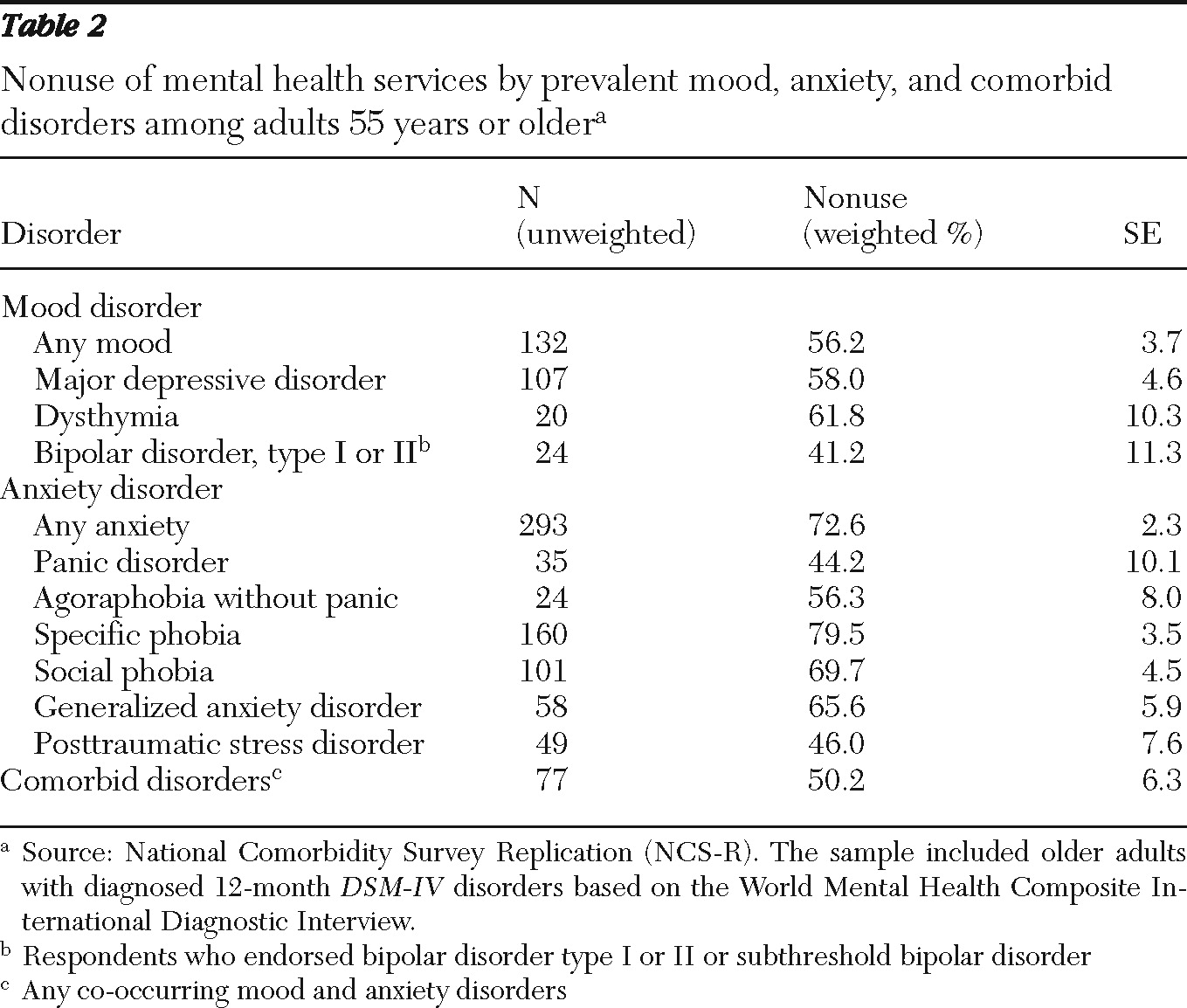

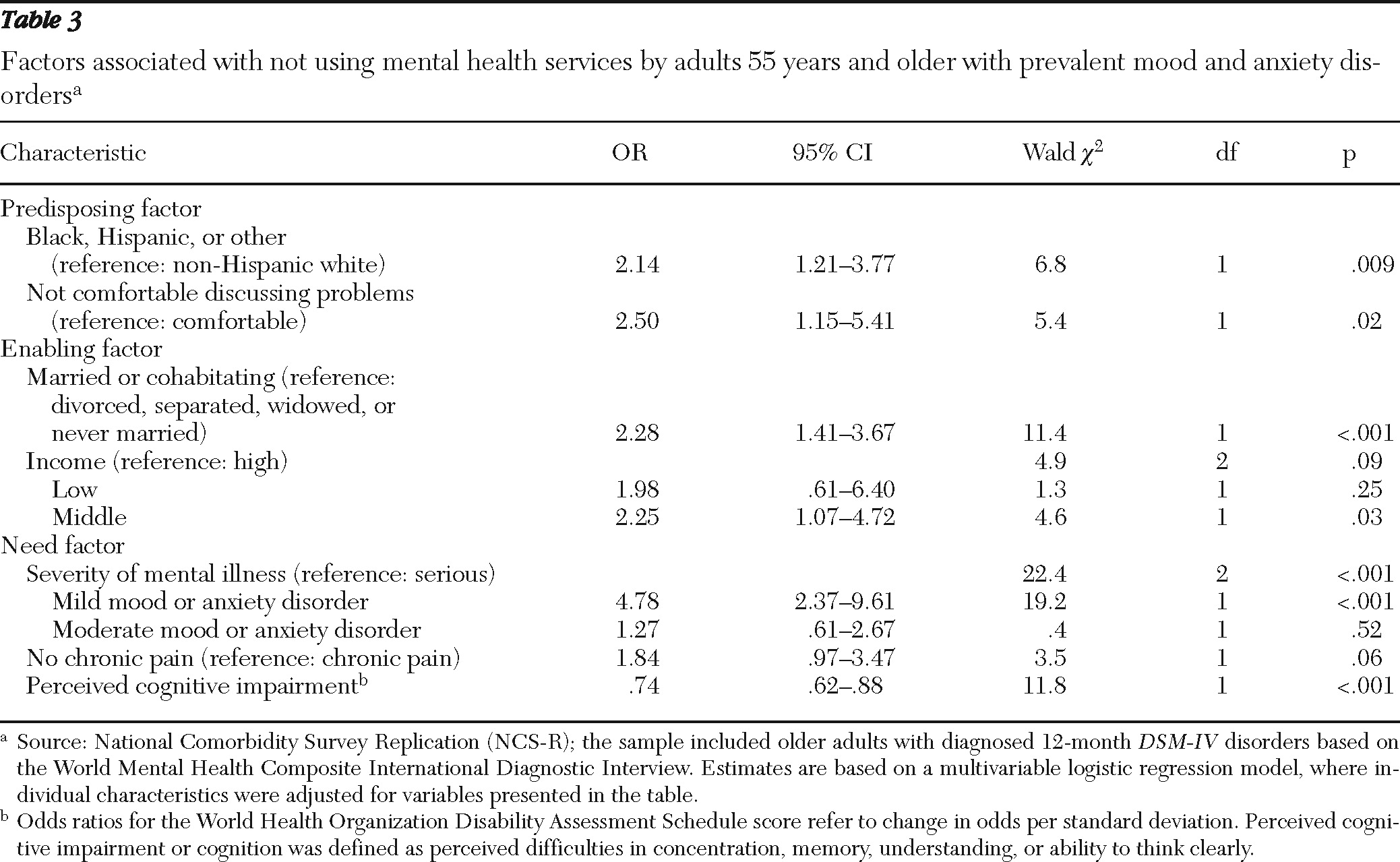

Among older NCS-R respondents with a 12-month anxiety or mood disorder, the vast majority did not use mental health services. Although the prevalence of nonuse was high across all predisposing, enabling, and need factors (>50%), not using services was most strongly related to racial-ethnic minority status, discomfort with seeking mental health care, marriage or cohabitation, middle income, mild mood or anxiety disorder, and no chronic pain or minor cognitive complaints. These findings suggest that low perceived need, moderate resources, and low motivation to use mental health care help to explain why services may not be sought, despite diagnosable mood and anxiety disorders.

Prior epidemiological studies have examined potential predictors of service use in the overall sample, pooling data of those with and without psychiatric disorders (

8–

10,

20–

26). Most of these studies have shown that the strongest predictors of use were recent diagnosis of a mental disorder and other medical conditions associated with need for care. For example, a study from the 2001 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the only variables associated with mental health services use by older adults were having at least one mental health syndrome and poor physical health (

10). Although such studies of pooled samples are informative, they do not explain why the majority of older adults symptomatic for a mental disorder do not seek care.

In this study, we found that low levels of mental and physical complaints were particularly important predictors of nonuse of services. This included mild complaints of mood or anxiety disorders' interrupting daily functioning (severity of disorder) and minor or no complaints about pain or cognition. These findings suggest that such minor complaints should be taken seriously, because they may equate to low perceived need for care among older adults with diagnosable DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders. Moreover, over 80% of respondents had chronic pain complaints, and most (approximately 70%) did not use mental health services, which suggests that many older adults with mood and anxiety disorders may present with somatic symptoms to their primary care physician and yet have little insight into psychological problems. Furthermore, use of mental health services by older adults with mild or moderate mood and anxiety disorders may have been low because these individuals received sufficient informal support and self-help; however, further investigation of this was beyond the scope of our study.

Even after adjusting for need factors, we found important effects of predisposing and enabling characteristics. However, although we found that respondents who were black or Hispanic or who were of a racial-ethnic background other than non-Hispanic white were more likely not to use mental health services, we did not find a significant effect of gender, age, or education, contrary to utilization studies that examined pooled samples with and without mental health disorders (

9,

20–

26). Yet similar to other studies examining use, in the overall sample we found that respondents who were married or otherwise not living alone were more likely not to use mental health services. This finding suggests that older adults who are symptomatic for a mental disorder and married or cohabitating do not perceive a need for mental health care and may not receive support for seeking care or may view their significant other as a surrogate of care. In contrast, this finding may indicate the power of relationship loss or strife as a motivator for seeking care (

37,

46). In addition, having a middle income was an enabling factor associated with nonuse, suggesting that resources available for treatment are more prominent among older adults with high or low income.

Although most prior research has suggested that stigma is a significant contributing factor to older adults' not using mental health services (

47–

49), we found that discomfort discussing personal problems with a professional was a more predominant predictor among older adults with mood and anxiety disorders. This finding may be attributable to defining stigma as being embarrassed to tell others about seeking help, suggesting the possibility of seeking help but hiding it from others, and defining discomfort as being uncomfortable interacting with a health care professional. Thus the negativity of discomfort implicates difficulty in initial seeking of help and high potential for discontinuation if help is sought. In contrast, when we focused our analyses on those with severe mood or anxiety disorders, we found that it was not stigma or discomfort which predicted nonuse but instead a lack of belief that mental health care will be beneficial.

The strengths of this study include a nationally representative probability sample, current DSM diagnostic assessment, and a comprehensive list of potential predictors selected on the basis of the well-established Andersen behavioral model of health services use. This study helps to describe the low use of mental health services in a nationally representative sample of older Americans with DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders. Our study is the first we are aware of to present key factors associated with not using mental health services among older community-dwelling U.S. adults with a mood or anxiety disorder.

Investigating patterns of nonuse of services among older adults has important implications for both policy and clinical practice, where findings support efforts at local and national levels to improve screening, awareness of need for care, and service availability for treatment of mood and anxiety disorders in late life. In particular, these results resonate with two overarching issues and recommendations identified by the New Freedom Commission: improving access and continuity and improving quality of mental health care (for example, with screening and prevention) (

11). Also, depression screening has been recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force as a preventive service under Medicare (

50). However, Medicare does not cover mental health screening as a benefit for most older adults (

50,

51). Ideally, health care reform will eventually increase such coverage, but currently it only expands payment of services already covered (

52). However, such change is vital, because coverage of preventive services would promote collaborative care and service integration, which would significantly increase access to and quality of care (

4,

50,

53) and improve the quality of life of older adults.

There were several limitations of this study. First, the NCS-R underrepresents homeless, institutionalized, and non-English-speaking older adults. Second, given issues of stigma, older adults with mental illness might have been less inclined to participate in a mental health survey. Third, even though the WMH-CIDI was shown to have good concordance with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

29), it is still a lay-administered interview. Therefore, the WMH-CIDI may not correspond to cases identified in clinical settings despite the use of similar diagnostic criteria. Fourth, some older adults with mood and anxiety disorders who responded to the NCS-R may have been excluded from the study because of difficulty recalling symptoms. Fifth, we cannot validate self-reported use of mental health services. Finally, although less than half of the sample was 65 years or older, which may limit generalizability to elderly adults, the NCS-R was limited in its assessment of mental health disorders considered common among older adults (including depression not otherwise specified, dementia with depression, mood disorders secondary to medical disorders, adjustment disorders with depression, and bereavement). Thus, given the above limitations, the estimates herein are probably conservative.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grants MH079093 and MH074717 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by grant AG031155 from the National Institute on Aging. The NCS-R was supported by grant U01-MH60220 from the National Institute of Mental Health, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, grant 044708 by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the John W. Alden Trust. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed otherwise.

Dr. Yaffe reports being a consultant to Novartis, Inc., for reasons not related to this project and serves on the data safety and monitoring boards for Pfizer, Medivation, Inc., and the Citalopram for Agitation in Alzheimer's Disease trial for the National Institute of Mental Health. The other authors report no competing interests.