Despite important initiatives to eliminate racial-ethnic disparities in mental health care (

1), African Americans, compared with white Americans, underutilize traditional mental health services (

2–

5). Discouragingly, the 2009 National Healthcare Disparities Report indicates that the gap for depression treatment between African-American and white adults is increasing (

6). Among the many factors that may contribute to African Americans' underutilization of traditional mental health services are stigma associated with mental illness (

7), distrust of providers (

8), and barriers to access, such as lack of insurance (

9). Given the debilitating nature of mental disorders (

10), especially among African Americans (

11), identifying ways to increase mental health service utilization in the black community is a vital public health concern.

Church-based health promotion programs have received increased attention as a way to reduce health disparities among African Americans (

12,

13). As defined by Ransdell (

14), church-based health promotion consists of “a large-scale effort by the church community to improve the health of its members through any combination of education, screening, referral, treatment, and group support.” The Black Church, which encompasses the seven predominantly African-American denominations of the Christian faith, is a trusted, central institution in many African-American communities that has been used as a setting for the delivery of health, social, civic, and political services (

15). Church-based health promotion programs have been used successfully in African-American churches to address health disparities for numerous medical conditions, such as cancer (

16–

21), diabetes (

22–

25), obesity (

26–

31), cardiovascular disease and hypertension (

32–

35), asthma (

36), and HIV/AIDS (

37,

38).

DeHaven and colleagues (

39) conducted a systematic review of 53 health programs in faith-based organizations from 1990 to 2000 to determine the effectiveness of these programs in providing health care services. Of note, they concluded that faith-based programs can improve health outcomes. However, only two of the articles reviewed identified mental illness as the study's primary focus. In one of these studies (

40), all participants were white, and in the other, the ethnicity of participants was not specified (

41).

The invaluable role of pastoral counseling and of African-American clergy as “gatekeepers” for mental health referrals has been described in detail (

42–

47). The therapeutic function of services in the Black Church has also been reported (

48–

53). However, these studies do not fall under the rubric of church-based health promotion programs, because they either focus exclusively on the activities of clergy or describe in general terms how the church can be a place of healing for members. Given the success of such programs in addressing health disparities for medical conditions among African Americans, we feel that a review of church-based health promotion programs for mental disorders is warranted. Thus we conducted a systematic review of published studies describing church-based programs for mental disorders among African Americans to assess the feasibility of using such programs as a strategy to reduce racial disparities in mental health service utilization.

Methods

We systemically searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ATLA Religion databases for articles that were published in peer-reviewed journals between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 2009. The following search terms, separately or in combination, were used: black/African American, church, church-based, faith-based organization, pastor, clergy, pastoral counseling, minister, mental health resource, mental health service, mental illness, depression, domestic violence, violence, drug use, substance use, treatment, and therapy. Several inclusion criteria were used. To be included in the review, studies had to be conducted in a church, with the primary objective of assessment of DSM-IV mental disorders (including nicotine-related disorders) or their correlates (suicide, trauma, and so forth) or perceptions of and attitudes toward these disorders or conditions. The primary objective could also be education about and prevention of these disorders or conditions or group support for or treatment of them. In addition, the number of participants had to be reported, as well as qualitative or quantitative data, or both. Finally, African Americans had to be the target population.

After duplicate articles were excluded, our initial search produced 1,451 studies for examination. Titles and abstracts were examined to identify studies that met our inclusion criteria. When the race-ethnicity of participants was not reported, we attempted to contact the corresponding author to obtain this information. This search strategy yielded 152 articles for formal review. We also checked bibliographies from articles identified in the search and previous review articles (

39,

54–

56) and found an additional 39 studies. In total, 191 articles were eligible for formal review.

The formal review process involved reading the article. Studies that focused exclusively on pastoral counseling and those in which all participants were pastors or clergy were excluded. Descriptive studies, studies not reported in English, and those not conducted in the United States were also excluded. After these exclusions, eight studies remained for inclusion in this review (

57–

64).

Results

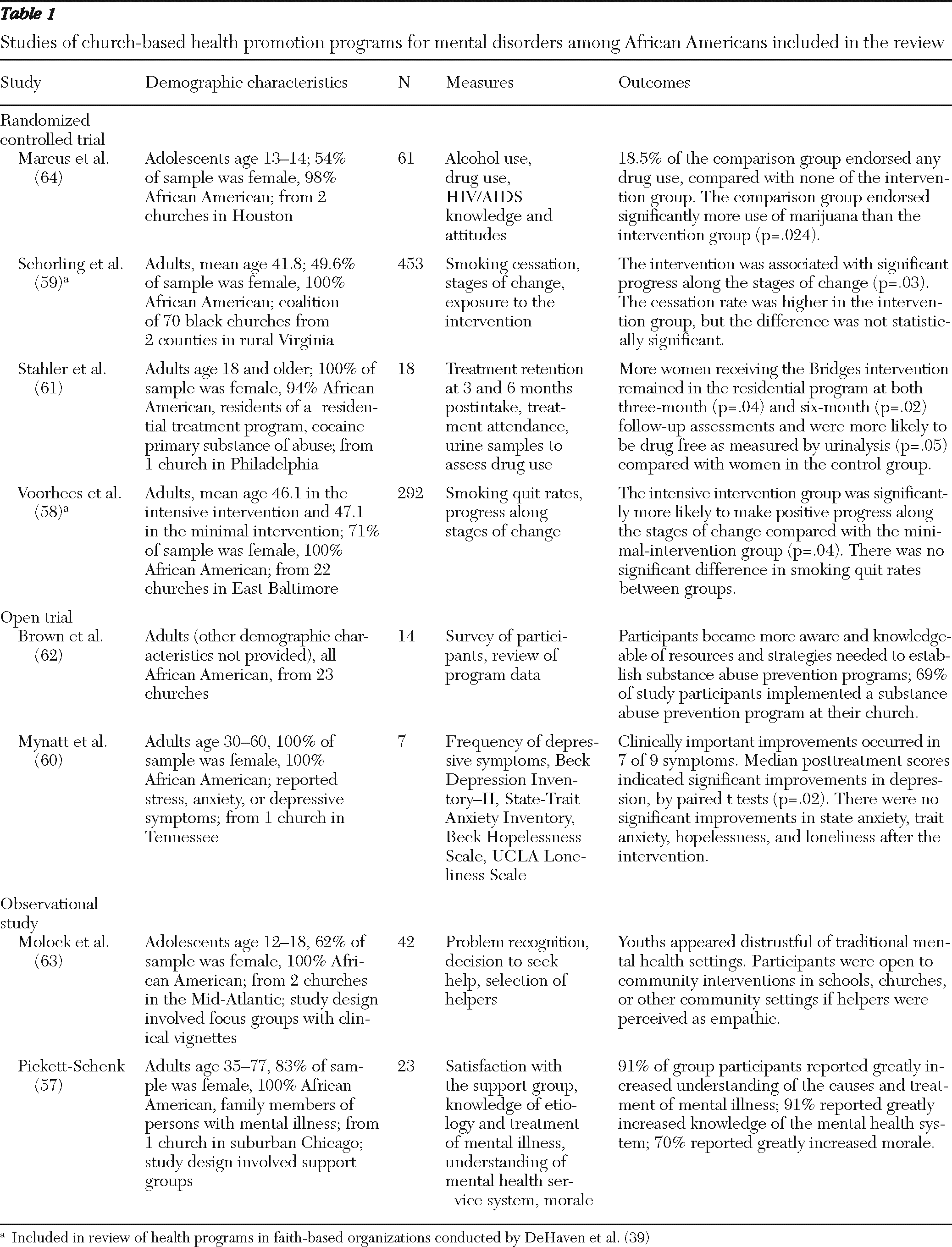

Four of the eight studies were randomized controlled trials, two were open trials, and two were observational studies. Six studies were designed to test the effects of a specific intervention, one involved a support group, and one involved focus groups. Across the eight studies, the total number of participants was 910; however, the number in each study varied considerably, from seven to 453. Six studies targeted adults. The psychiatric disorders addressed most commonly were substance-related disorders (in five studies). Only one study focused on depressive and anxiety symptoms; however, it had only seven participants.

Table 1 summarizes the studies of church-based health promotion programs included in this review.

Among the randomized controlled clinical trials, Marcus and colleagues (

64) conducted a faith-based intervention to reduce substance abuse among African-American adolescents. The 61 participants (54% females) included adolescents who were recruited from two local churches. The intervention, Project BRIDGE, involved risk prevention alternatives and in-depth information about substance abuse. When outcomes were evaluated, the control group endorsed significantly more use of marijuana (p=.024) and more use of any drugs (p=.011) in the past 30 days than the intervention group. Use of any drugs was reported by 19% of the control group and by none of the BRIDGE participants. The authors concluded that the church-based intervention was successful in preventing illicit drug abuse among youths.

Schorling and colleagues (

59) conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine whether smoking cessation interventions delivered through a coalition of black churches would increase the smoking cessation rate of church members. The 453 participants, half of whom were women, were from two rural Virginia counties and were assigned randomly by county to the intervention or control group. The intervention involved smoking cessation counseling for the participants as well as distribution of devotional booklets at churches. Participants in the intervention group made significantly more progress along the stages of change from baseline to follow-up than participants in the control group (p=.03). The authors concluded that smoking cessation interventions for African Americans can be implemented successfully through a coalition of black churches.

Stahler and colleagues (

61) also utilized a coalition of black churches to provide mentors and settings for a faith-based intervention, Bridges to the Community, to treat African-American women with cocaine abuse or dependence. The 18 female study participants lived at a residential treatment program. The Bridges intervention consisted of interactions with a church mentor and group activities at a nearby church. Compared with women in the control group, significantly more women who received the Bridges intervention remained in the residential program at both three-month (p=.04) and six-month (p=.02) follow-up assessments. Tests of drug use via urinalysis at the six-month follow-up showed that 75% of participants in Bridges and 30% of participants in the control group were drug free (p=.05). The authors concluded that use of black churches to enhance residential drug abuse treatment appears feasible.

Voorhees and colleagues (

58) conducted a randomized controlled trial to study smoking quit rates and progression along the stages of change for smoking cessation. The 292 participants (71% female) were recruited from 22 churches in East Baltimore. On the basis of the church they attended, participants were randomly assigned to either an intensive, culturally sensitive, spiritually based intervention (11 churches) or a minimal self-help intervention (ten churches). At one-year follow-up assessments, positive progress along the stages of change was highest among participants from Baptist churches who received the intensive intervention. Baptists in the intensive intervention were 3.2 times more likely than other participants to make positive change progress (p=.01). The authors concluded that the spiritual nature of the intensive intervention, along with structural factors of specific denominations (that is, Baptist), made the church a feasible setting in which to develop health promotion and disease prevention strategies for underserved African-American populations.

In an open trial, Brown and colleagues (

62) conducted a three-year study to provide training and technical assistance to black churches to develop and implement alcohol and illicit substance abuse prevention programs. The majority of the research activities—quarterly training workshops, cluster meetings, and technical assistance—tookplace in a church setting. Of the 14 participants, for whom no demographic information was provided, pre- and poststudy scores showed a statistically significant increase in participants' knowledge of developing research proposals (p=.003), recruiting and training volunteers (p=.012), and developing substance abuse prevention programming (p=.001). Most participants (69%) surveyed reported that they provided substance abuse prevention programming at their church as a result of the intervention. The authors concluded that churches can effectively implement substance abuse prevention programming.

Mynatt and colleagues (

60) conducted an open trial of group psychotherapy at a church to reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms, hopelessness, and loneliness among African-American women. The 12-week intervention, INSIGHT therapy, is a cognitive-behavioral therapy approach designed specifically for women (

65,

66). Seven women were recruited by announcements in the church bulletin. Mean length of depressive symptoms among study participants was ten years. Median posttreatment scores on the Beck Depression Inventory II and the State Anxiety Inventory were lower than pretreatment scores. Significant changes in depression were observed when the data were analyzed with paired t tests (p=.02). The authors concluded that developing culturally acceptable interventions that reduce risk of anxiety and depressive disorders among African-American women is paramount.

In an observational study, Molock and colleagues (

63) utilized clinical vignettes among African-American adolescents to explore their perceptions of hypothetical help-seeking behaviors if they or someone they knew were confronted with a suicide crisis. The 42 participants (62% female) included adolescents (12–18 years) who participated in 90-minute, coeducational focus groups conducted at two local churches. About three-fourths (32 of the 42 participants) knew of at least one peer who had either attempted or completed suicide. Nearly all participants reported that it was important for suicidal individuals to get immediate help. However, very few selected mental health professionals as helpers. Youths were open to community-based programs located in schools, churches, or other community settings. The authors concluded that suicide prevention programs for African Americans should include an educational component and that youths may be distrustful of traditional mental health care providers.

Pickett-Schenk (

57) conducted educational support groups on mental disorders for African-American families. Twenty-three participants (83% female), each of whom had a family member with mental illness, attended support groups held at a metropolitan church. No treatment was provided to participants in the support groups or directly to their family members as part of the study. Prestudy outreach activities conducted at the church included provision of educational booklets on the causes and treatment of mental illness, a telephone hotline for crisis intervention services, and a half-day workshop on mental illness. Nearly all participants (91%) reported that the groups greatly increased their understanding of the causes and treatment of mental illnesses, and 70% felt that support group participation greatly increased their morale. The author concluded that church-based support groups provide families of persons with mental illness with valuable knowledge and emotional support.

Discussion

Research on church-based health programs for

DSM-IV mental disorders and their correlates among African Americans is sparse. Our review covers a 30-year period, and yet we identified only eight studies for inclusion in this review. Most studies included in this review focused on substance-related disorders, making it difficult to make inferences about church-based health programs for other mental disorders. However, the Black Church is a prominent, trusted institution in many African-American communities that already provides “de facto” mental health services for many of its members (

67). Because African Americans have higher reported rates of church attendance and religiosity than members of other racial-ethnic groups (

68,

69), the Black Church may be uniquely positioned to overcome barriers such as stigma, distrust, and limited access that contribute to racial disparities in mental health service utilization. On the basis of our findings, we discuss below themes in church-based health programs for mental disorders and suggest areas of future research.

A common element in many of these studies was that church-based interventions for mental disorders were culturally tailored to emphasize black culture and spirituality. In a study on smoking cessation, Voorhees and colleagues (

58) distributed audiotapes of gospel music and booklets with Biblical scriptures. Stahler and colleagues (

61) developed a faith-based intervention for women with cocaine addiction that stressed black culture and a spiritual worldview. In view of the hypothesis of Jackson and colleagues (

70) that many African Americans may smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, and use drugs to cope with the chronic stressors of racism and harsh living conditions (for example, poverty, poor housing, and crime), utilizing culturally modified interventions in church-based health promotion programs may have a greater impact than traditional interventions on reducing substance-related disorders among African Americans.

Conversely, many churches may struggle with addressing moral issues, such as illicit sexual and criminal activity, that are associated with substance use disorders (

71,

72). Such conflicts may limit the ability of church-based health promotion programs to provide comprehensive services to all participants with substance-related disorders. When potentially controversial issues are the main focus of such programs, Thomas and colleagues (

72) suggested that secular agencies and public health professionals can be utilized to provide appropriate resources. In addition, researchers can collaborate with church leaders to frame the topic in a manner that is congruent with doctrinal tenets of the church (

71,

72). The successful implementation of church-based health promotion programs in the studies described in this review suggests that black churches can be used as a setting in which to address sensitive issues such as substance-related disorders.

The one study that focused on depressive and anxiety symptoms was an open trial that included only seven participants (

60), which limited the study's power to detect statistically significant differences in outcomes. Participants reported lower depressive and state anxiety symptoms after completing the study. Because only one study with a small sample has been published, it is clear that research on church-based health promotion programs for depression is currently underdeveloped. Acknowledging this limited body of evidence, we suggest that such programs for depression could satisfy cultural preferences for depression treatment among African Americans. For example, in one study African Americans in primary care settings expressed a preference for counseling over taking medications to treat depression (

73); in another study, African Americans were three times more likely than whites to cite intrinsic spirituality (that is, prayer) as an extremely important part of depression care (

74). Future studies should examine African Americans' attitudes about the feasibility and acceptability of providing church-based depression care.

Only two of the studies targeted adolescents (

63). Molock and colleagues (

63) focused on suicidality and help-seeking behavior, and Marcus and colleagues (

64) conducted a church-based intervention for substance-related disorders. Findings of both studies suggested that community-based resources for mental health care may be more acceptable to black adolescents. Although these studies are encouraging, more research is needed to address suicidality and substance use among black teens. From 1980 to 1995, the suicide rate increased by 119% for African Americans age ten to 19 years, driven largely by a 214% increase in completed suicides by males (

63,

75). Because adolescent males have lower rates of church attendance than adolescent females (

76), church-based health promotion programs are likely insufficient by themselves to address the mental health needs of black males and reduce their suicide rates. We propose that future studies should examine the feasibility of utilizing such programs for black teens and explore the feasibility of other community-based venues as resources in which to engage African-American adolescents in mental health care.

Methodological insights from several studies highlighted the importance of collaborating with the church community. In two studies, investigators developed a coalition of black churches in which pastors collaborated with researchers on ways to best engage their congregants as study participants (

59,

62). Marcus and colleagues (

64) explicitly utilized principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR), in which members of the target population are engaged in the entire research process from planning to implementation, analysis, and evaluation (

77). A recent review concluded that CBPR has “great potential for helping reduce mental health treatment disparities among minorities and other underserved populations” (

78). Church-based, collaborative research processes could help build trust and reduce stigma associated with research that is especially strong in the African-American community (

8,

79–

81).

Our study must be assessed in light of several limitations. First, we did not include descriptive articles; only articles that reported qualitative or quantitative data were reviewed. This eliminated articles that described collaborative efforts between mental health professionals and churches (

82). Second, several of the intervention studies had a small number of participants, which limited their ability to detect statistically significant differences between study outcomes. Third, because of the limited number of studies included in this review (N=8) and different types of data, we did not conduct a meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of the studied interventions. Fourth, because all of the studies were conducted in Christian churches, we cannot comment on the presence or absence of health promotion programs in other religious settings, such as synagogues or mosques.

Conclusions

Reducing racial disparities in mental health service utilization is an important and complex issue for which there is no single solution. The current literature on church-based health promotion programs for mental disorders among African Americans is extremely limited. Therefore, any conclusions about the role of the Black Church in mental health care should be interpreted cautiously at present. We recognize that there may be large, vulnerable groups (such as black adolescent males) who may not be reached by church-based health programs. However, given the success of church-based programs to address disparities for numerous medical conditions, we believe that the Black Church is currently being underutilized as a potential mental health resource. More intensive empirical investigation is needed to establish the feasibility of black churches to provide mental health screening, treatment, education, and other services for African Americans.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant T32 MH19126 from the Program for Minority Research Training in Psychiatry, American Psychiatric Association; grant T32 MH015144 from the National Institute of Mental Health; and funding from the Templeton Foundation. The authors thank Diane Brown, Ph.D., David Cross, Ph.D., Jennifer Kunst, Ph.D., and Dennis Morgan, Psy.D., for their assistance in clarifying the race-ethnicity of participants in their respective studies. The authors also thank Nicole Stewart, B.A., for her assistance with the preliminary literature search.

Dr. Weisman receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Perseus Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, and MultiHealth Systems. Dr. Hankerson reports no competing interests.