Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based, intensive, outpatient cognitive-behavioral treatment for persons who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder. Borderline personality disorder is characterized by enduring patterns of instability in emotion regulation, impulsivity, self-image, and interpersonal relationships (

1). A standard outpatient DBT package, as tested in randomized controlled trials (

2–

4), includes multiple concurrent components, each mapped to the essential functions of a comprehensive treatment: one year of weekly individual psychotherapy aimed at improving motivational factors, one year of weekly group skills training to enhance capabilities, as-needed phone consultation with the individual therapist to promote generalization of skills to the natural environment, case management to help the patient structure his or her environment, and weekly consultation team meetings for DBT therapists to enhance therapist capabilities and motivation to provide effective treatment (

5).

Many studies of this intensive outpatient model have demonstrated DBT's effectiveness in alleviating mental health problems among women who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder (

4,

6–

9). Multiple studies have supported DBT's effectiveness in significantly reducing the frequency of self-injurious behaviors (

3,

4,

10), the number of days of hospitalization for psychiatric or suicidal reasons (

2,

3,

10), the number of emergency department visits for psychiatric or suicidal reasons (

2,

3), and the expression of intense anger (

3). In controlled studies at 12- and 16-month posttreatment follow-up assessments, patients who received DBT also showed greater increases in global functioning (

11,

12) and social adjustment (

13,

14) than patients who received usual treatment (

2,

9,

12). DBT has been shown to be effective in reducing suicidal behaviors and other target symptoms of borderline personality disorder in several samples, including patients in the Netherlands (

4), female veterans (

7), women with drug dependence (

9), and a small sample of men (

15).

It is common for individuals with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder to be admitted to inpatient psychiatric units. According to Widiger and Weissman (

16), 72% of patients who meet criteria for the disorder will be hospitalized at least once, and many studies have shown that persons with this disorder have more inpatient hospitalizations than those with other mental disorders (

17), along with frequent readmissions (

18). For example, in a sample of 290 inpatients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, 79% reported at least one previous hospitalization (

19). In a longitudinal, multisite study of patients with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses, those who met criteria for borderline personality disorder were nearly four times as likely as those with major depressive disorder to be hospitalized over a three-year period (

20), and the proportion reporting past hospitalizations (72%) was higher than among those with diagnoses of other personality disorders (schizotypal, 51%; avoidant, 36%; and obsessive-compulsive, 23%) (

21). Another study, which followed patients with borderline personality disorder for ten years, found that the frequency of hospitalizations declined over the study period; however, the frequency was significantly higher than among patients with diagnoses of other personality disorders (

22).

Psychiatric hospitalizations are useful for some patients some of the time, but they are undesirable for other patients for a variety of reasons, including stigma and disruption of work, school, or interpersonal relationships (

23,

24). Hospitalizations are also costly; one study found that the mean±SD annual cost of psychiatric inpatient services was $7,948±$4,317 for a person with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder who was already engaged in outpatient care (

25). Although psychiatric hospitalization is known to be a disruptive event, many persons with borderline personality disorder continue to be hospitalized.

Self-injurious behavior, either suicidal or nonsuicidal, is often the primary reason for hospitalization of persons who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder (

26), likely because recurrent suicidal behavior is among the diagnostic criteria for the disorder (

1). This population has a completed suicide rate 50 times greater than that of the general population (

27). Clearly, after a suicide attempt, medical stabilization is essential. However, subsequent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization may not be the best option for reducing the frequency of suicidal behavior among individuals with borderline personality disorder (

28). Some authors have raised concerns about contagion effects of suicide among inpatients, although the data are mixed (

29–

31). Further, Linehan (

5) has suggested that psychiatric hospitalization may reinforce suicidal behaviors, depending on the function of such behaviors for each patient. From a DBT perspective, if the function of suicidal behavior is the communication of distress or the desire for companionship or avoidance of some aversive process in daily life (including solving one's problems independently), then being hospitalized may inadvertently reinforce the suicidal behavior. If a suicidal threat or behavior functions in such a way and is followed by hospitalization, then the individual may be more likely to engage in suicidal threats or behaviors again, which may create a drain on the mental health system and prevent patients from developing functional coping skills to address their underlying problems, leading to a cycle of symptom exacerbation and hospitalization.

Such concerns about the effects of hospitalizing a patient, coupled with the high cost of inpatient services, highlight the importance of an evidence-based outpatient treatment for borderline personality disorder, such as DBT, that focuses on providing skills and a support structure to prevent individuals from requiring inpatient services. However, the reality is that many patients with this disorder (as well as other suicidal patients who do not meet criteria for borderline personality disorder) are not sufficiently or actively engaged in outpatient treatment, and others experience periodic exacerbation of symptoms that is greater than their providers feel comfortable managing on an outpatient basis (

22). As the data indicate, many of these patients will likely require temporary inpatient treatment. Thus it is important to develop effective inpatient treatment for stabilizing patients with this disorder, preparing them for engagement in long-term outpatient therapy, and teaching them skills to minimize the likelihood of future hospitalizations and to improve their psychosocial functioning and quality of life.

There is no consensus about what treatment works best for inpatients with borderline personality disorder. However, the success of DBT in outpatient settings suggests that it may be effective in reducing symptoms of the disorder in inpatient settings, especially in terms of teaching patients to prioritize treatment goals and learn crisis survival skills. Several reports document the use of DBT in inpatient settings with a variety of samples, including women (

13,

32) and adolescents (

33,

34). However, we could not identify any reviews or meta-analyses on this topic that systematically compared the effectiveness of inpatient DBT across samples of patients with symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to characterize different modifications of standard DBT that have been delivered in inpatient settings and to report on the effectiveness of the DBT treatment strategies implemented in such settings to reduce target symptoms associated with the disorder. We conducted a systematic review of published empirical studies. Here we report our findings and make recommendations for researchers, regarding DBT implementation and symptom measurement, and for clinicians, regarding best practices for inpatient DBT.

Methods

Data collection and analysis for the review followed the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) outlined by Liberati and colleagues (

35). PsycINFO, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases were searched for any relevant articles published before June 2011. Combinations of the following search terms were used to identify articles for inclusion: dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), borderline personality disorder, inpatient, hospitalization, and short-term treatment. Published, peer-reviewed articles within bibliographic databases, including case studies reporting outcome data, were selected for inclusion if they met three criteria: they reported on implementation of some version of DBT; the treatment was delivered in an inpatient setting; and the purpose of the treatment was to address symptoms related to borderline personality disorder, including but not limited to suicidal behavior, self-injurious behavior, or overtly aggressive behavior, as well as other psychiatric symptoms (for example, symptoms of depression and anxiety). The study samples need not have comprised only patients with borderline personality disorder; however, for inclusion in the review, all patients in the samples needed to endorse recent suicidal or out-of-control behaviors consistent with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder.

Articles were excluded if DBT was used in an inpatient setting to address symptoms not related to borderline personality disorder (for example, disordered eating behaviors), if the inpatient treatment was not adapted specifically from Linehan's published DBT text (

5), or if DBT was administered in any setting other than an inpatient psychiatric unit (for example, a forensic hospital, jail, or residential program). On the basis of the final exclusion criterion, the results of this review can be considered to apply only to DBT treatments administered in a voluntary inpatient unit. A focus on DBT programs operated in forensic or residential programs is beyond the scope of this review, although these are worthy topics for future study.

We examined the references of all included articles to identify other relevant publications. We determined eligibility of each article separately, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. We did not contact study authors to obtain additional information. Rather, we based our review on the descriptions and results provided in the published, peer-reviewed publications.

Two of the authors (JMB and ENW) each independently extracted data from the articles. When this process was completed, a third author (TS) independently repeated the data extraction process conducted by the other two authors and reviewed studies for results about similar variables (for example, if one study reported rates of suicidal ideation, other studies were subsequently double-checked for such rates). Disagreements were resolved by consensus—that is, by closely reading the relevant study material again and discussing the content. One author (TS) completed the final step by checking each study for reported effect sizes.

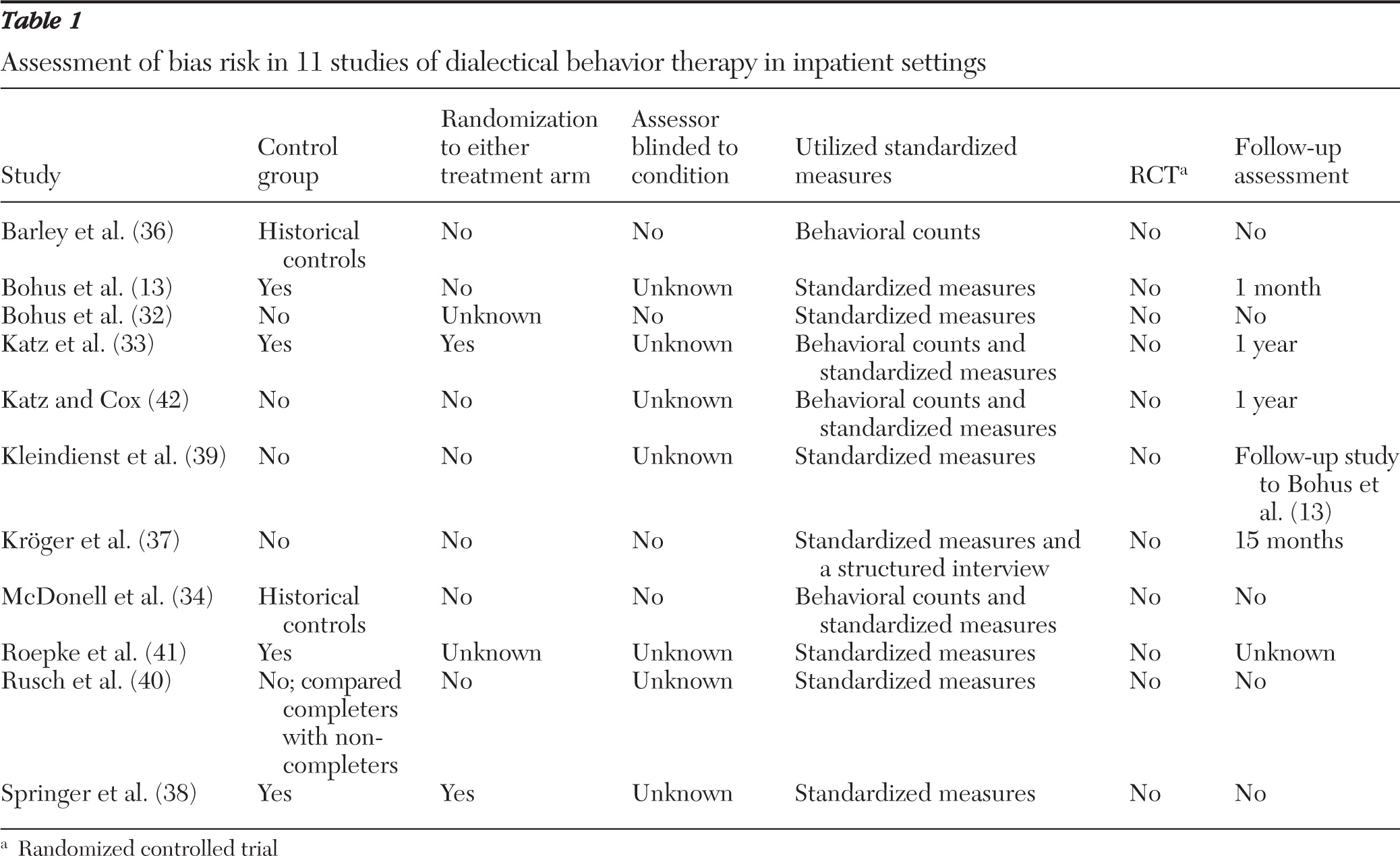

Initially, information was collected from each study on characteristics of the sample receiving DBT (age, race, and gender) and of the comparison sample and on how DBT was implemented or modified. All outcome measures used and any follow-up results were also documented. After the review began, the authors decided to collect any information about treatment as usual for the comparison groups and effect sizes. To determine the risk of bias in each study, one of the authors (ENW) assessed for several methodological factors in each study (

Table 1) in accordance with the published PRISMA guidelines (

35) for the conduct of systematic reviews.

Results

Use of the search terms listed above identified 22 articles. Six were book chapters or descriptive papers, not empirical studies presenting original results. After a thorough review of the remaining 16 articles, we excluded five because a full DBT program was not implemented (two articles) or the study was conducted in a forensic rather than a voluntary inpatient setting (three articles). Our final sample consisted of 11 studies in which DBT was implemented in an inpatient setting with patients who had a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder or who exhibited symptoms consistent with the disorder.

Most of the studies included samples of women only. Four included both men and women (

33,

36–

38). For each study, we provide demographic information about the DBT and comparison groups (when available), the treatment setting, and the specific DBT strategies implemented (noting how they compare with the five modes of standard DBT), as well as outcome measures and findings. [A table summarizing this information is available online as a data supplement to this article.]

DBT implementation

Because a single, standard formulation for inpatient DBT has not been developed and empirically supported, the treatment packages described in the articles varied considerably. However, the authors of all the studies claimed to operate from a DBT framework and utilized at least one mode of standard outpatient DBT. Variations in clinical procedures are described in more detail below. Bohus and colleagues (

32) provided information about treatment phases but did not describe specific treatment strategies used. In addition, both Kleindienst and colleagues (

39) and Rusch and colleagues (

40) reported on later follow-up assessments of the cohort that had been described earlier by Bohus and colleagues (

13) and thus did not include a description of the treatment package utilized.

Treatment duration.

Treatment lengths ranged from two weeks (

33,

38) to three months (

13,

36,

37,

41), which was the modal duration of treatment.

Individual therapy.

Standard outpatient DBT includes weekly individual therapy sessions, which generally last 60 minutes (

5). Of the eight studies that described specific treatment strategies, only one did not include individual therapy in the treatment package (

38). Frequency of individual therapy ranged from one 60-minute session per week (

37,

41) to two 60-minute sessions per week (

13,

33,

42). Four studies followed standard DBT practices (

5) for individual therapy (

13,

34,

37,

41). One study utilized psychodynamically trained therapists who adhered to Linehan's (

5) treatment hierarchy, emphasized acceptance and change, and taught behavioral coping strategies (

36). In two studies, weekly individual therapy sessions focused on reviewing the patient's weekly diary of relevant behaviors and use of DBT skills and conducting behavioral analyses of maladaptive behaviors but did not involve teaching of DBT skills (

33,

42).

Group skills training.

Standard outpatient DBT includes a weekly 2.5-hour skills training group that involves teaching skills in four domains—mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness (

43). All of the studies that described a modified DBT treatment package for inpatient use included a variation of the skills training group. Frequency of skills training groups ranged from one 90-minute session weekly (

36) to 45- to 75-minute sessions daily (

33,

38,

42), with most studies including two to five hours of skills training each week (

13,

36,

37,

41).

The content of the groups varied considerably across studies. Four studies followed the standard DBT skills training manual (

43) in the groups (

13,

34,

37,

41). Three studies adapted the standard DBT skills curriculum for daily use (

33,

38,

42). In another study, Kröger and colleagues (

37) added a self-management module to the group. Similarly, Barley and colleagues (

36) reported not following the standard DBT manual but nevertheless focused skills training efforts on the four skills domains presented in Linehan's manual.

Consultation.

In standard DBT (

5), therapists engage in phone consultations outside of sessions to help develop patients' ability to effectively ask for help, to promote generalization of skills to daily life, and to conduct brief skills coaching, especially when a patient is in acute distress. None of the articles reviewed described the use of phone consultation with the individual therapist. However, in five of the studies, patients had the opportunity to consult with milieu staff or skills coaches at any time to promote generalization of skills to their daily lives on the unit (

13,

33,

34,

36,

42).

Therapist consultation groups.

Standard outpatient DBT (

5) also includes weekly therapist consultation group meetings. The purpose of these meetings is to ensure that therapists have the knowledge, skills, and motivation to provide DBT with fidelity to the model and to prevent therapist burnout (

5). Six studies included weekly or biweekly therapist consultation groups in the treatment package (

13,

33,

34,

36,

41,

42). The content of therapist consultation sessions was not described in any of the reports.

Additional treatment components.

Some studies utilized additional treatment components not included in the standard outpatient DBT manual. [These are noted in the online data supplement to this article.]

Comparison groups.

To claim treatment effectiveness, symptom reductions in the treatment group must be significantly greater than those in a comparison group. Single-group designs significantly limit internal validity. Of the 11 studies reviewed, seven conducted analyses in which groups of participants who received some form of DBT were compared with some type of comparison group. Of these seven studies, only two assessed and reported on the specific components of treatment received by the comparison group (

33,

38). This omission is a serious methodological concern in treatment research on inpatient DBT, and thus results on the effectiveness of inpatient DBT from most studies reviewed here should be interpreted with caution. Specifically, omission of information about comparison groups prevented us from evaluating the extent to which contamination occurred, with DBT techniques delivered to patients in control groups, or from assessing other notable similarities or differences in, for example, therapist training and duration or intensity of treatment.

Treatment outcomes

Across all 11 studies, the DBT treatment group demonstrated improvement in at least one symptom or problematic behavior at one or more time points. Below we present detailed results by symptom category. All symptom reductions discussed represent a statistically significant pre- to posttreatment reduction in the specific symptom for the DBT group (compared with the control group when noted). Effect sizes ranged from very small to large.

Self-harm behavior.

Eight studies examined self-harm behavior, and reductions were found in six (

13,

32–

34,

36,

42). Of these, three included a comparison sample and reported favorable effects of DBT versus the control condition (

13,

33,

36). The longitudinal follow-up to Bohus and colleagues' (

13) study found that improvements in self-harm behavior were maintained up to 21 months postdischarge (

39). Further, self-harm behaviors increased in one study that encouraged in-depth discussion of self-injury during group sessions (

38), a practice inconsistent with standard DBT.

Depressive symptoms.

Eight studies examined depressive symptoms, and six found a significant reduction in these symptoms after treatment (

13,

32,

37,

38,

41,

42). Of these, three demonstrated symptom reduction beyond that of a comparison sample (

13,

38,

41). These improvements were maintained up to 21 months postdischarge (

39). Also, Katz and colleagues (

33) reported a reduction in depressive symptoms for their DBT group, but the reduction was not significantly different from that in their comparison sample of adolescents receiving treatment as usual.

Dissociative experiences.

Three studies examined dissociative experiences. On the basis of Dissociative Experiences Scale scores, such experiences were reduced at one month postdischarge in two studies (

13,

32). One of these studies included a comparison group, and the DBT group showed greater improvement (

13). These reductions were maintained at 21 months postdischarge (

39).

Anxiety symptoms.

Three studies examined symptoms of anxiety. Such symptoms were reduced at one month postdischarge in two studies (

13,

32). One study included a control group, and the reduction was greater for the DBT participants (

13). These improvements in anxiety symptoms were maintained at 21 months postdischarge (

39).

Anger and hostility.

Four studies examined anger and hostility (

13,

32,

38,

39). Anger was reduced at posttreatment in one (

32), but this study did not include a comparison group. Another study found that at one month postdischarge, anger ratings were the only area that had not shown a significant reduction (

13).

Suicidal ideation.

Two studies examined suicidal ideation. In one, reductions in suicidal ideation scores of DBT participants were significantly greater than for the comparison group (

38). In the other study, Katz and colleagues (

33) found a reduction in suicidal ideation, although it was not significantly different from that of the comparison group. The case study we included showed a decrease in suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up (

42).

Violent behavior.

Two studies looked at violent behavior. In one, reductions of violent incidents in the DBT group exceeded those in the comparison sample (

33). Aggression, as measured by the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R), was significantly reduced at posttreatment in one study, although the study did not include a comparison group (

32).

Interpersonal problems.

Only one study examined interpersonal problems. Bohus and colleagues (

13) found that such problems were reduced at one month posttreatment, and reductions exceeded those in the comparison group.

Global adjustment.

Six studies examined global adjustment. Scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and the global severity index of the SCL-90-R indicated greater improvements in the DBT group than in a control group at one month posttreatment (

13); the improvements were maintained at 21 months posttreatment (

39). Kröger and colleagues (

37) found that at a 15-month follow-up, scores on the global severity index of the SCL-90-R decreased for DBT participants and GAF scores increased. However, this study did not include a comparison sample. Finally, McDonell and colleagues (

34) reported significant improvements in global functioning for the DBT group compared with a control group as measured by the Child-Global Assessment Scale.

Identity disturbance.

One study measured aspects of constructs that the authors called “self-concept clarity” and “facets of self-esteem” (

41). The study found enhancements in self-concept, including self-regard, social skills, social confidence, and basic self-esteem, in the DBT groups compared with a control group, suggesting that DBT may have affected aspects of the identity disturbance criterion of borderline personality disorder (

41).

Discussion

Summary of findings

Published data on the effectiveness of inpatient DBT suggest that as adapted by a variety of research teams, this treatment may be effective in reducing symptoms of borderline personality disorder. The studies reviewed here describe improvements across multiple domains of functioning. Different adaptations of DBT in inpatient settings appear to facilitate reductions in the symptoms of borderline personality disorder, including self-harm behaviors (

13,

33,

36,

39,

42), depressive symptoms (

13,

32,

33,

37,

38,

41,

42), anxiety symptoms (

13,

32), and dissociative experiences (

13,

32,

39), in addition to increasing global adjustment (

13,

34,

37,

39). There is some support for the notion that inpatient DBT can lead to reductions in hostility and anger (

13,

32) and suicidal ideation (

33,

38), although more evidence is needed.

Further, many of these treatment gains were maintained after hospital discharge (

13,

32,

42). In fact, one study demonstrated maintenance of positive treatment effects up to nearly two years postdischarge (

39). These findings provide preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of DBT techniques used on inpatients units serving individuals admitted with symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Katz and colleagues (

33) and Springer and colleagues (

38) found significant reductions in depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and self-harm behaviors compared with stringently constructed comparison groups, demonstrating the effectiveness of inpatient DBT in addressing such symptoms. However, many of the other studies failed to include comparison groups, and we therefore must be cautious about drawing strong conclusions about the efficacy or effectiveness of the DBT programs described here.

It is important to study inpatient treatments for use with individuals who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder because of the high rates of inpatient hospitalization (

8) and readmission (

18) in this population. Knowing that persons with this disorder are likely to be admitted to inpatient units, clinical staff in these settings must be equipped with evidence-based practices to improve functioning in this notoriously difficult-to-treat population. Evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that outpatient DBT is effective in reducing self-harm behavior and improving functioning among women with borderline personality disorder (

10,

12,

14). Given the strong evidence that DBT reduces symptoms of this disorder, it seems a logical choice for adaptation in inpatient settings.

In this systematic review, we aimed to synthesize and evaluate published studies of DBT strategies used for inpatients with borderline personality disorder. We identified 11 studies that represent the foundational work in this area. The findings are promising because they provide preliminary support for treating patients with symptoms of this disorder by using various formats of DBT delivered across a variety of inpatient settings.

Limitations and future research

Although the literature provides initial evidence of the effectiveness of using DBT strategies to treat inpatients with borderline personality disorder, methodological limitations make it difficult to draw strong conclusions and to compare findings across studies. As shown in

Table 1, the studies discussed here varied considerably in methodological rigor. First, none were randomized controlled trials, which prevented the study authors from making direct claims about the efficacy of inpatient DBT for borderline personality disorder. In addition, only seven of the 11 studies included comparison groups, and detailed information about the conditions to which the comparison groups were exposed was provided in only two of the seven articles. Given the lack of rigorous control in these studies, it is impossible to definitively state that symptom reductions represent actual clinical improvement rather than regression to the mean or simply improvements attributable to the passage of time. Additional limitations include differences in the modification of DBT across studies, variability in the measures used and time points at which outcomes were measured, variability in treatment settings, and small and homogeneous samples. Additional research is needed to address these limitations in order to provide stronger evidence for the effectiveness of this treatment in hospital settings.

Further, the review examined only studies in which DBT was implemented in hospital settings with patients in voluntary treatment. Studies of DBT in forensic and residential settings were excluded, and our findings cannot be generalized to those types of settings. Inpatient DBT may need to be organized differently in forensic settings for a variety of reasons, including the fact that patients are usually not engaged in treatment voluntarily. One study that was excluded from our review because it was conducted in a forensic setting showed that inpatient DBT may not be suitable for forensic patients because of their violent behavior (

44). However, another study that was excluded from our review found reductions in violent behavior in the DBT group compared with the treatment-as-usual group (

45). Although traditional DBT may not be useful in forensic settings, research has been conducted to adapt Linehan's treatment (

5) for use in forensic settings (

46), and models of DBT are being developed for use in these settings (

47). Future research is needed to test the effectiveness of these adapted treatments in a variety of therapeutic settings.

Although a standard formulation of DBT in an outpatient setting has been developed (

5) and empirically supported (

2–

4), implementation of the total DBT package (including all five modes of treatment) has not been adapted for inpatient use in a systematic way. Rather, many of the studies reviewed here appear to reflect individual research teams' attempts to modify and apply DBT in their own unique inpatient psychiatric setting. DBT is meant to be applied flexibly and functionally; thus we take no issue with these research groups' approaches. However, the substantial variation in treatment protocols across trials limits our ability to compare them and to identify specific aspects of treatment that might contribute uniquely to symptom reductions. Therefore, researchers would be wise to develop a structured DBT program for use in inpatient settings, and test and replicate its efficacy in a stepwise fashion, as suggested, for example, by Rounsaville and colleagues (

48). This program should outline and standardize procedures to the extent possible across unique settings, including the duration of treatment, modes of treatment, frequency of individual therapy and skills training sessions, and minimum specific content to be included. Given that we cannot draw conclusions about which components of inpatient DBT contribute to clinical improvement, it is best to maintain fidelity to standard outpatient DBT as much as possible, because there is evidence that straying from existing DBT principles is associated with poorer outcomes (

38). If standardized inpatient DBT packages demonstrate effectiveness in reducing symptoms and improving functioning, studies will be needed to empirically determine which treatment components serve as mechanisms for symptom improvement and sustained behavior change.

In addition to standardizing a treatment protocol for inpatient DBT, future research must improve upon and standardize the research methods used to assess the treatment. Published studies varied on many aspects of study design, such as inclusion criteria, constructs of interest included in the analyses, measures used to assess a given construct, and length of time between follow-up assessments. This variation significantly limited our ability to compare studies. Thus future trials of inpatient DBT for borderline personality disorder should be consistent in their research methods, including use of the same (validated) measures to assess symptoms and measurement of outcomes at similar time points—we suggest at admission or pretreatment, at discharge or posttreatment, and then at follow-up assessments at one month and one year postdischarge. The purpose of inpatient treatment is to stabilize patients, and studies therefore should assess the impact of inpatient DBT on suicide attempts, nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and frequency of inpatient readmission and emergency room visits. In addition, researchers should assess domains relevant to borderline personality disorder, including depression, anxiety, interpersonal skills, and global functioning, by using standardized measures at each time point (for example, the Beck Depression Inventory, the State-Trait Anxiety Index, and the GAF).

Refining the design of studies that assess DBT in inpatient settings will promote effective comparison across studies and clarify the effectiveness of this treatment for borderline personality disorder. Considering that only two studies included here assessed and reported on the treatment of the comparison groups (

33,

38), future studies testing the effectiveness of inpatient DBT should both assess and report specific characteristics and therapy experiences of comparison groups (for example, demographic characteristics and the type, duration, and frequency of mental health treatment).

The findings of many studies reviewed here suggested the maintenance of treatment gains after discharge (

13,

32,

39). However, few articles reported the type of psychological services used by patients after their hospital stays. Good clinical practice would indicate follow-up outpatient care (for example, stepped-down treatment). However, few articles reported the proportion of participants who obtained such follow-up care or who were fully engaged in follow-up care, whether it included pharmacotherapy alone or a combination of medications and behavioral treatment. Kleindienst and colleagues (

39) reported that a majority of their sample (58% at 21 months postdischarge) was engaged in “some sort of psychotherapy,” but they did not report further details. Also, none of the articles discussed whether patients who received inpatient DBT began or resumed outpatient DBT after discharge. Given the chronic and debilitating nature of borderline personality disorder, short-term inpatient DBT may be insufficient to effect long-term gains in symptom management or clinically significant functional improvement on a large scale. Therefore, more controlled studies of follow-up treatments for inpatient DBT should be conducted.

Finally, it is possible that inpatient DBT may be most effective as an “intensive orientation” to standard outpatient DBT, although this was not examined in any of the studies reviewed. Short-term inpatient DBT might be thought to serve as an effective strategy for stabilizing patients, reducing acute suicidal ideation, promoting control over suicidal or self-injury urges, and decreasing behaviors that interfere with therapy to prepare patients to engage successfully in outpatient DBT. Increased engagement at the outset of outpatient therapy and consistency between inpatient and outpatient treatment style and strategies may be associated with favorable treatment outcomes in the longer term. Research examining the efficacy and effectiveness of inpatient DBT as an intensive orientation to outpatient DBT is the next step in developing best-practice guidelines for inpatient units for use with patients who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder. Research on engaging patients in intensive inpatient DBT followed by standard outpatient DBT may find that this treatment sequence represents a future gold standard for treating patients with borderline personality disorder.

Conclusions

Overall, evidence suggests that that there is clinical utility associated with implementing DBT in inpatient treatment settings, because it seems to be effective in reducing symptoms of borderline personality disorder and improving global functioning when standard practices and principles are incorporated with fidelity to the treatment model. However, additional research is needed to standardize inpatient DBT and outcome measurement, identify critical mechanisms of symptom and behavior change, and assess the effectiveness of follow-up outpatient treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.