Soldiers returning from combat often face a postdeployment period in which there is an increased risk of readjustment stressors, such as problems with family, marriage, or employment. This period can also be marked by the onset of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Coping with the additional burden of PTSD likely complicates soldiers' ability to cope during the readjustment period. Accordingly, research has documented a relationship between PTSD and greater readjustment stress among soldiers serving in recent conflicts (

1) or in previous ones (

2,

3).

Many soldiers with a mental health need do not seek care within the first year of their readjustment period. An estimated 23%–44% of returning soldiers with PTSD or other mental health problems receive treatment within the first year (

4,

5). Linking returning soldiers who have PTSD with treatment is a national priority because effective treatments for PTSD are available (

6,

7) and PTSD sufferers who seek treatment experience symptom relief more quickly than those who do not (

8). Therefore, research is needed to better understand the process by which returning soldiers with PTSD seek treatment.

Readjustment stressors may be a key motivator for treatment seeking. Veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) often seek help for financial, occupational, and other readjustment concerns. A qualitative study suggested that returning soldiers are most likely to seek mental health treatment when problems emerge within family and occupational roles (

9). Accordingly, one study showed that combat veterans seeking care from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) expressed most interest for services related to veterans' benefits (83%) and schooling, employment, or job training (80%) (

1). Also, at least one study has found a positive association between mental health treatment seeking and readjustment stress (

5). However, because the study examined the effect of readjustment stressors in a sample with and without mental disorders, it may be that readjustment stressors are more common among veterans with a mental disorder. Less clear is whether these stressors differentiate PTSD sufferers who go on to seek treatment from those who do not.

Therefore, research is needed that further establishes the role of readjustment stressors in treatment seeking among PTSD sufferers, especially given that those suffering from this disorder may be more likely to be affected by readjustment stress (

1). Such information can be valuable in policy and program development. Consistent with this aim, this study examined the role of readjustment stress as a predictor of mental health care seeking among returning soldiers with likely PTSD. We hypothesized that readjustment stressors are significantly related to seeking mental health care. This study built on the existing literature by using survey responses obtained from members of the New Jersey National Guard (NJNG) during reintegration events after a one-year deployment to Iraq. The survey collected information from veterans who did and did not seek mental health care, both within the Veterans Health Administration and from community-based providers. Also, our analyses considered only veterans who met criteria for likely PTSD, in order to identify factors associated with help seeking, given the need for PTSD treatment. With this sample, we describe the prevalence of readjustment stressors, their relationship to depressive and PTSD symptoms, and their association with early mental health treatment seeking.

Methods

Participants

With support from the New Jersey Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, we collected data anonymously in September 2009 from 1,665 of 1,723 NJNG soldiers who were attending postdeployment reintegration events three months after returning from a 12-month tour in Iraq. Twenty-nine attendees at the reintegration did not complete the survey, and an additional 29 were excluded because of poor data quality as judged by three independent raters, yielding a response rate of 97%. The sample was surveyed as part of a larger, longitudinal study assessing the mental and physical health effects of serving in the NJNG. This study focused on the 179 NJNG soldiers who met criteria, based on self-report, for PTSD at three months postdeployment.

Data collection

Anonymous and self-administered surveys were distributed to all NJNG members attending the reintegration events, which were held on four days over two consecutive weekends. The surveys were administered to soldiers in groups of approximately 45–75. Participation was voluntary, and NJNG leadership was not aware of soldiers' survey completion status. Soldiers received no monetary incentive for participation. All research procedures were approved by the Rutgers University and VA New Jersey Healthcare System Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

PTSD was assessed with the PTSD Checklist (PCL), which is a 17-item self-report scale (

10,

11). This study focused on respondents who produced a positive PTSD score (≥50). This criterion has been used frequently in PTSD research, including studies with veterans (

11,

12), and has been shown to have adequate sensitivity and specificity with a PTSD diagnosis based on a structured psychiatric interview (

13). We measured PTSD severity as a continuous variable based on the PCL score.

Depression was assessed with the commonly used nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (

14) and analyzed as a continuous variable. Readjustment stressors were assessed with a nine-item scale that inquired, using the following stem, whether a number of stressors occurred: “Did any of the following things trouble you during your deployment to Iraq or after you returned home?” Items inquired about marriage, financial, and family problems. The items for this measure were developed on the basis of qualitative interviews that elicited common readjustment experiences among New Jersey National Guardsmen. Participants indicated yes or no to each stressor, yielding a score of 0–9, with acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach's

α=.76).

Utilization of mental health care

Questions about mental health service use inquired about visits that occurred since returning home (postdeployment). We first asked whether participants had a visit with a “mental health professional” for a “mental health problem.” Respondents were provided with examples of mental health professionals, such as psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and counselors. Responses were used to code for any mental health visit postdeployment. Second, participants were asked whether they received a “doctor's prescription” for antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers, or sedatives. A response of yes concerning any of these medications was used to code “prescribed a psychotropic postdeployment.” Given that pharmacotherapy is often provided by non-mental health physicians (that is, primary care physicians), we defined any mental health visit postdeployment as either having a mental health visit postdeployment or receiving a prescription for a psychotropic postdeployment. This was the study's key outcome.

Analyses

All analyses were completed with SPSS, version 16.0. Because of a 17% missing value rate for the variables pertaining to mental health visits, a missing value analysis assessed whether the missing values were related to age, gender, race-ethnicity, and marital status and produced a nonsignificant value of Little's missing completely at random test. This signified that the values were missing randomly, and 22 cases with missing values therefore were not analyzed.

Analyses first described rates of mental health visits that had been made within three months postdeployment. Next, chi square analyses examined whether demographic variables were significantly different among those with or without any mental health visit postdeployment. Significant variables were later used as covariates in the multivariate analyses. Chi square analyses then compared whether those having a visit differed according to individual readjustment stressors, as well as categories of cumulative number of stressors reported. Correlations were then generated to examine the relationship between readjustment stressors with the PCL score (Spearman rho), where PCL scores were categorized into tertiles because of nonnormal score distributions. Also, a Pearson correlation was generated between readjustment stress and PHQ-9 scores. The final analysis used hierarchical logistic regression to examine the association between readjustment stress and any mental health visit after controlling for the relevant mental health and demographic characteristics. The independent variables were entered into the model in three blocks. Block 1 included readjustment stress only. In block 2, we added the mental health variables PTSD and depression. Block 3 included all of the above variables plus the statistically significant demographic variables.

Results

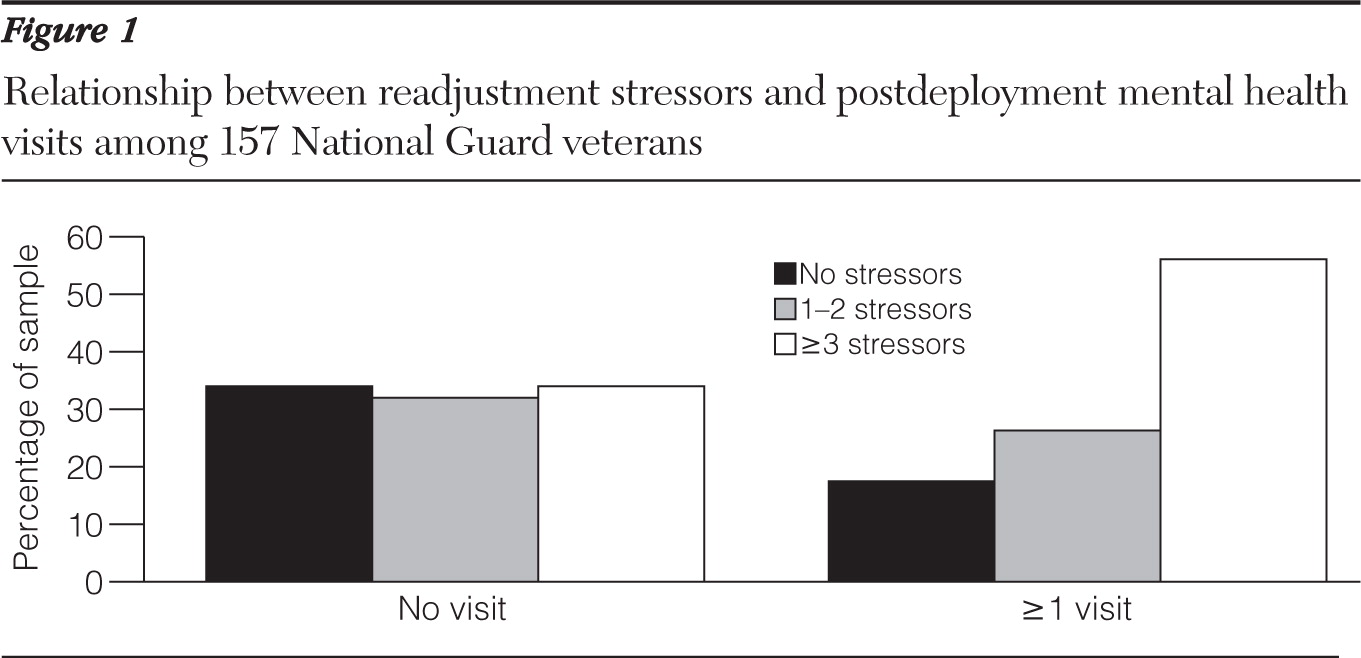

A total of 179 (11%) respondents scored positive for PTSD, and our analyses focused on the 157 who did not have missing utilization data. The rates for several types of mental health visits are summarized in

Table 1. Rates of treatment contact ranged from 23% to 36% for the three-month postdeployment period, depending on the type of contact. Most visits occurred with a mental health professional, and the medications most commonly prescribed were antidepressants and sedatives.

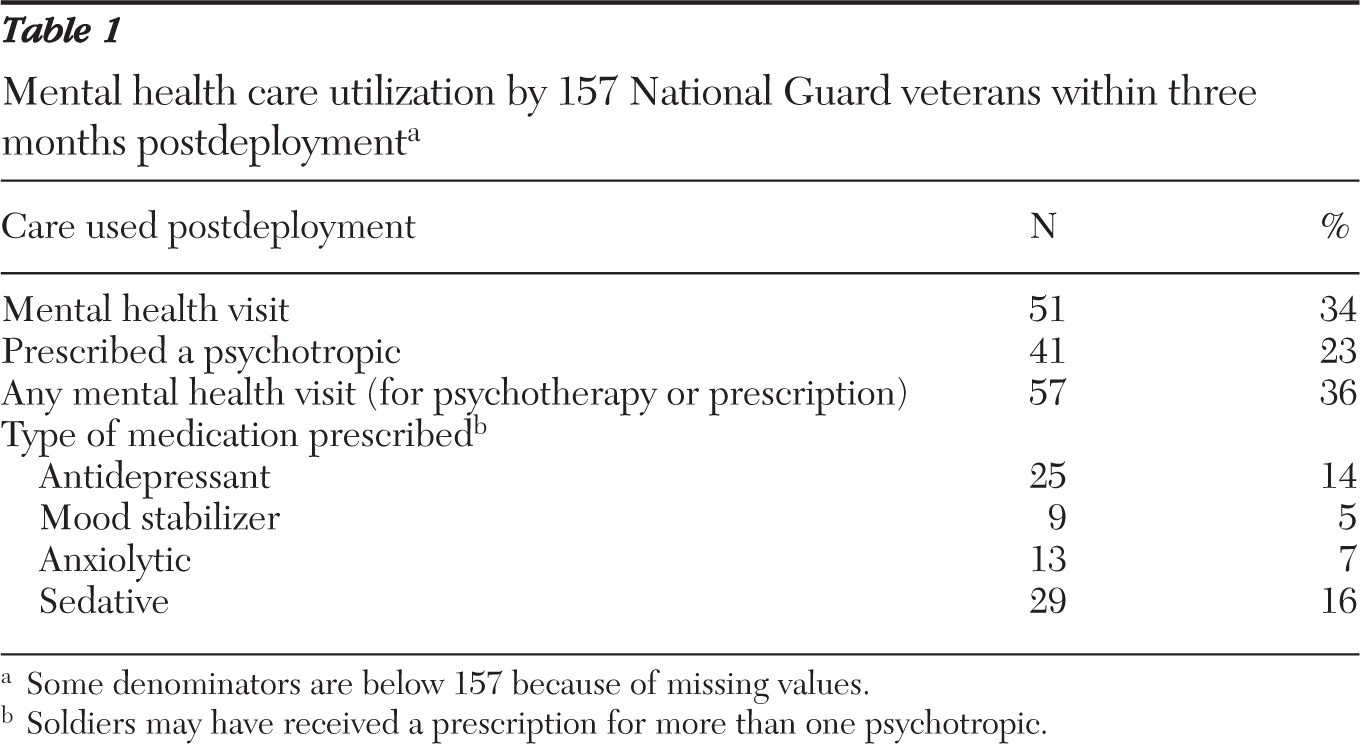

Table 2 summarizes the rates of having any mental health visit postdeployment, according to demographic characteristics. Having a mental health visit significantly differed by age and marital status. Pairwise comparisons showed that National Guard soldiers who had any mental health visit postdeployment were more likely to be married or living with a partner (

χ2=10.5, df=1, p<.001) and separated, divorced, or widowed (

χ2=11.5, df=1, p<.001), compared with those who were single. Having a visit was also more likely among soldiers ages 26–39 (

χ2=4.1, df=1, p<.05) and 40–70 (

χ2=8.3, df=1, p<.01), compared with those who were ages 17–25.

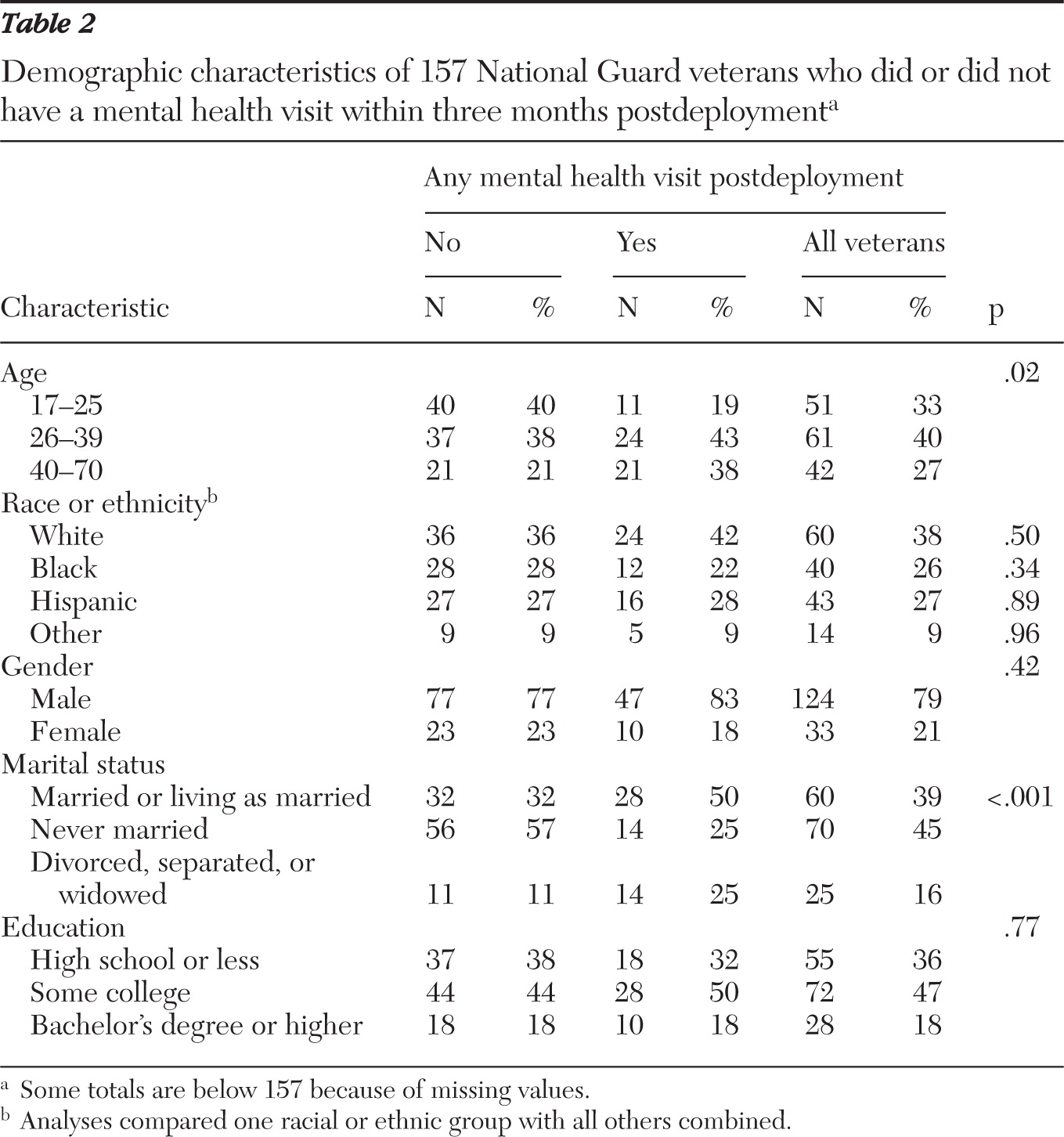

Table 3 shows the relationship between any mental health visit postdeployment and PTSD severity, depression, and each of the individual readjustment stressors. First, PTSD symptom severity was not significantly related to utilization of mental health services. In contrast, having a visit was associated with a higher PHQ-9 depression score (greater depression).

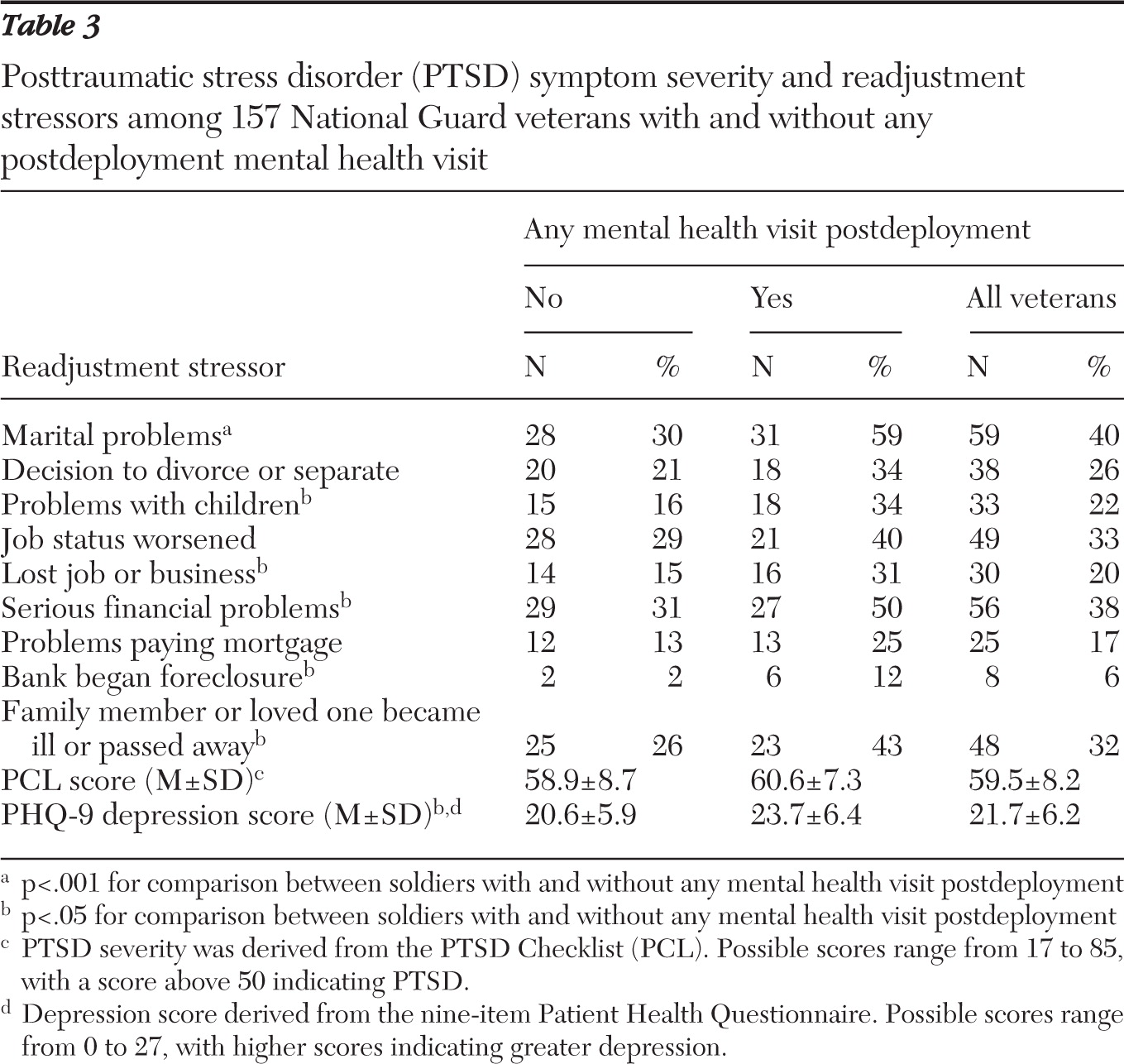

Table 3 also shows that significant negative life events were not uncommon in this group. Events as serious as job or business loss and marital separation or divorce were reported by 20% and 26% of the sample, respectively. Illustrating a cumulative effect, higher levels of these readjustment stressors were significantly associated with having any mental health visit postdeployment (

χ2=8.7, df=2, p≤.05) (

Figure 1). In total, most soldiers experienced a readjustment stressor, with only 28% experiencing no stressors. Next, results showed a significant number of readjustment stressors and a significant correlation between them and PCL score (analyzed in tertile categories; r

s=.21, p≤.05) and PHQ-9 score (r=.26, p≤.001).

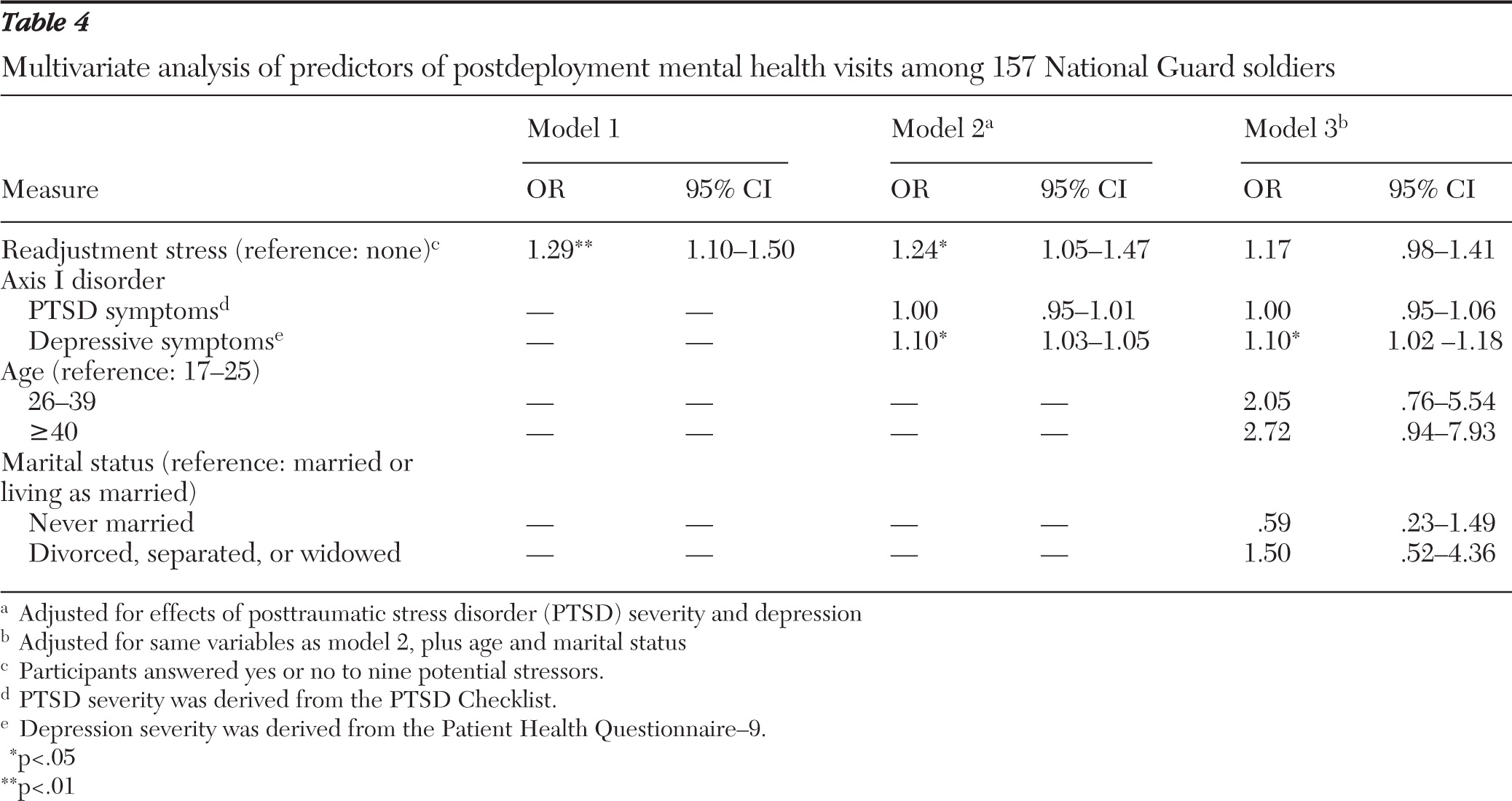

Finally,

Table 4 presents the results of multivariate models examining the prediction of any mental health visit postdeployment by level of readjustment stressors. Model 1 shows that National Guard soldiers with the highest accumulation of readjustment stressors were more likely to have any mental health visit postdeployment. Model 2 adjusted for the effects of PTSD symptom severity and depression and found a mostly undiminished, statistically significant effect for readjustment stressors. This step shows that depression was also related to having a mental health visit. PTSD severity was not statistically significant. In model 3, which added age and marital status variables, readjustment stressors were no longer significant but depression was.

Discussion

Key findings

The findings of this study, showing relatively low rates of early treatment seeking among returning soldiers, are consistent with previous literature (

15). We found that only 34% of National Guard veterans who scored positive for PTSD had made a postdeployment mental health visit and that psychotropic medication had been prescribed to only 23%. The rates of medication usage in this study were slightly lower than those reported by Kehle and colleagues (

16), in which 30% of OIF National Guard soldiers with PTSD received psychotropic treatment. The rate differences between this study and those reported by Kehle and colleagues may be accounted for by the length of time in which utilization was assessed, which varied across the studies (three months versus up to six months, respectively). The 11% of respondents in our sample who scored positive for PTSD was also comparable with that found in the Kehle and colleagues study.

Results were mixed in terms of meeting the treatment needs of OIF soldiers with PTSD. It is estimated that 7% of the U.S. population with PTSD seeks care within the first year of onset, and our results show that more OIF National Guard soldiers were engaging with early mental health care compared with their civilian counterparts (

17). This finding provides some support for recent policies, such as five-year access to Veterans Health Administration care among soldiers serving in Iraq or Afghanistan, increased education and awareness of combat-related stress, and routine assessment of mental health conditions (

18,

19). However, the treatment utilization rate reported for National Guard soldiers with PTSD means that approximately two-thirds were without any early mental health treatment contact. Thus additional policies and strategies for screening and referral should be considered for improving treatment participation rates.

In terms of this study's key objective, we found that readjustment stressors played a significant role in early treatment seeking. Six out of nine readjustment stressors were individually associated with having any mental health visit in the univariate analyses (

Table 3). This effect was cumulative, with higher numbers of stressors being associated with higher rates of service utilization. The association between readjustment stressors and mental health service use was independent of the severity of PTSD or depression symptoms. As noted, this relationship diminished considerably on adjustment for age and marital status. Also, depression levels remained a significant predictor of service use, even after adjustment for age and marital status. The finding that depression was a significant variable associated with help seeking is consistent with previous research (

5,

20).

The loss of significance of readjustment stress after analyses adjusted for demographic characteristics is likely due to our sample characteristics and the relationship of readjustment stress with age and with marital status. Researchers have suggested that readjustment stressors may be more relevant for National Guard soldiers, who tend to be older and have more developed familial and occupational roles than members of the active military components (

5).

The results of this study, along with previous research, provide some support for this interpretation. First, our sample of National Guard soldiers appeared to be older compared with samples from active-duty components studied by Hoge and colleagues (

15) and others (

21). Second, in our somewhat older sample, individual readjustment stressors were reported at high levels, with each often reported by more than 20% of the participants. For example, 20% had lost their job or business, which compares with an unemployment rate of 9.8% in New Jersey during the period when these data were collected (September 2009) (

22). A similar rate (28%) of job loss was found in a previous study with reserve-duty soldiers with PTSD (

23). Third, a previous study using the same data set found that readjustment stressors were more common among National Guard soldiers who were older and either married or previously married (

24). Combined with our finding that readjustment stressors were no longer significant after analyses adjusted for age and marital status, these observations lend support to the view that National Guard soldiers tend to be older and more susceptible to the type of readjustment stressors assessed in this study. This is because they will likely have more involved family and occupational roles that can be affected by their symptoms.

Limitations

To interpret the loss of significance of readjustment stress after adjustment for demographic variables, one should consider the types of readjustment stressors captured by our scale. Its items tap stressors that pertain more to veterans who are or who have been married. Note, however, that the scale used in this study was based on qualitative interviews with New Jersey National Guardsmen and was designed to capture the readjustment stressors that were most salient to this sample. Nevertheless, it is important to interpret these findings in terms of the specific readjustment stressors that were assessed (marital problems and job problems). Unmarried soldiers may experience stress in areas that were not captured in our survey of readjustment stressors, which mainly inquired about marital, child, and occupational difficulties. Future studies should examine a broader array of readjustment stressors to better sort out their relationship to help seeking among soldiers varying in age range and marital status. A recently published scale may improve our ability to study this issue, given its broader range of stressors assessed (

25).

The significance of readjustment stressors in the rate of early treatment seeking has useful implications for services designed to treat PTSD among soldiers. PTSD service delivery models may consider meaningfully integrating interventions that help with marital and family functioning, as well as case management support for addressing financial and occupational stressors. Also, motivation for treatment can be built by linking the goals of treatment to better functioning with family and occupation. Given that PTSD treatment may be characterized by considerable attrition, addressing these issues may improve treatment retention rates by aligning services with key motivators for seeking treatment (

20,

26). Also, outreach and awareness efforts can utilize readjustment stressors as a point of engagement, which would increase the numbers of veterans who visit with a professional and would be more likely to be screened and referred to treatment. Future studies can build on this research by examining the degree to which returning soldiers cite readjustment stressors as their reason for seeking care. Future studies can also examine the role that family members play in encouraging care seeking.

There are other limitations worth noting. First, although the use of a three-month postdeployment window was advantageous for studying early treatment contact, it provided a very limited window for examining treatment continuity. Second, it is critical that engagement occur within a context of optimal treatment quality. Given the importance of treatment quality, we caution that our data could not describe involvement with empirically supported psychotherapies for PTSD or other care quality indicators, such as wait times (

6,

7,

27). We also did not have the data to describe the type of mental health visit utilized or the type of professional that was contacted (psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy background, psychologist, psychiatrist, or informal source of care). Third, the data lacked information on the soldiers' perspectives regarding PTSD and its treatment. Such data are critical for understanding participants' own reasons for seeking care. Thus future studies should clarify whether soldiers report readjustment stressors as reasons for seeking care. Fourth, it is likely that a portion of soldiers with PTSD symptoms at postdeployment will recover on their own. Our cross-sectional design did not allow for an estimate of early mental health care seeking that accounts for those who may have a natural recovery (

28). Yet it is important to note that our PCL cutoff of ≥50 likely identified a cohort of veterans with more severe PTSD symptoms that are less likely to naturally remit. Still, future research can build on the results of this study by incorporating a longitudinal design that can describe the natural remission among those who do not seek early mental health care.

Conclusions

Readjustment stressors among returning National Guard soldiers were fairly common, with many soldiers reporting multiple occupational, financial, and family stressors. Readjustment stressors generally were associated with having an early mental health visit, and these effects appeared to be accounted for by older age and marital status. Most returning soldiers with PTSD do not seek early treatment, but rates of having a mental health visit were more favorable in this population than in the general population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by a grant from the New Jersey Department of Military and Veterans Affairs.

The authors report no competing interests.