A logical way of tackling this challenge is to understand what causes wards to differ in rates of conflict and containment. Conflict refers to any patient action that threatens patient or staff safety, such as physical violence, verbal aggression, absconding, use of alcohol or illegal substances, self-harm, and medication refusal. Containment refers to any method that psychiatric staff use to prevent or manage the conflict event, such as seclusion, special observation, searching procedures, deescalation, time-out, manual restraint, and enforced medication (

5).

For some years, our research team has investigated factors within wards that explain differences in conflict and containment rates and actions that can minimize conflict and containment. In one of the largest studies we have conducted so far, the City-128 study of more than 100 wards, we explored the relationship between conflict and containment levels and patient characteristics, the service environment, the physical environment, ward routines, staff numbers (by discipline), and a range of factors related to staff group functioning. We have previously published findings of multiple linear regression examining the association of these variables and conflict and containment. A number of features, for example, social deprivation of the area served by a ward, were significantly associated with higher rates of conflict and containment (

6). However, we also reported, counterintuitively, that the correlation between conflict and containment was weak, albeit statistically significant (r=.25, p=.003).

Because this finding implied that there were a number of wards where conflict was at high levels but use of containment was low and vice versa, we sought to find a way of further interrogating our data to illuminate these differences. This article reports the results of an investigation to determine variables in our data set that were associated with high and low conflict and containment, particularly in wards with high conflict and low containment or low conflict and high containment. This kind of secondary analysis offers a new approach in understanding the types of factors that are more or less likely to yield a therapeutically positive ward environment.

Results

A scattergram of wards by total conflict and containment scores is displayed in

Figure 1. Lines indicating median scores produced four quadrants. Wards with low conflict and low containment sit within a small area, indicating little variation, whereas wards with high conflict and high containment vary considerably from one another in their rates of conflict and containment. The distribution demonstrated that the division of wards into a typology of four is not natural, given that wards did not group within the quadrants. Thus the categorical differences we identify below represent underlying continua or dimensions.

Table 1 displays the variables showing statistically significant differences among the four types of wards.

Figure 2 summarizes the findings of the multivariate analysis comparing the four types of ward. Subquadrant 1.1 indicates in bold type the variables that were significantly different on the high-conflict, low-containment wards compared with the other three conditions. The variables that were significantly different between the high-conflict, low-containment wards and the high-conflict, high-containment wards, the low-conflict, low-containment wards, and the low-conflict, high-containment wards, respectively, are listed in subquandrants 1.2–1.4. Variables that appear in more than one subquadrant are italicized.

Comparing the upper and lower halves of

Figure 2 enables the identification of features that were associated with high and low rates of conflict. Compared with low-conflict wards, wards with high rates of conflict served areas of high social deprivation and a higher proportion of patients with schizophrenia, patients who were formally detained under mental health legislation, and patients who were admitted for risk of harm to others. These distinguishing features were attributes of the patients admitted rather than of the wards or their staff.

Comparing the left and right halves of

Figure 2 enables the identification of features that were associated with high and low rates of containment. Consistent differences are harder to see, but higher containment may have been associated to some degree with larger wards (more beds) and the degree of organization of the ward and its program. Variance in containment rates was less clearly associated with any features of the ward, its staff, or the patients who were admitted.

The unique features of high-conflict, high-containment wards (those differentiating them from the other three categories) were their high levels of unqualified staff and use of high levels of temporary staff. They were also predominantly associated (variables differentiating them from two of the other three categories) with a high total staff number and with a high proportion of legally detained patients.

Low-conflict, low-containment wards had no unique features but were predominantly associated with service to an area of low social deprivation and a low level of formally detained patients.

Low-conflict, high-containment wards were uniquely larger and predominantly featured fewer patients with schizophrenia, detained patients, and patients admitted for risk of harm to others. It is the large size of the ward that was linked to these outcomes, given that all conflict and containment rates were standardized to bed numbers prior to analysis.

The unique features of high-conflict, low-containment wards were a worse physical environment quality and a greater proportion of staff who are male. They also predominantly featured a lower proportion of white British staff, served an area of greater social deprivation, and admitted higher proportions of patients for risk of harm to others, patients with schizophrenia, and patients subject to legal detention.

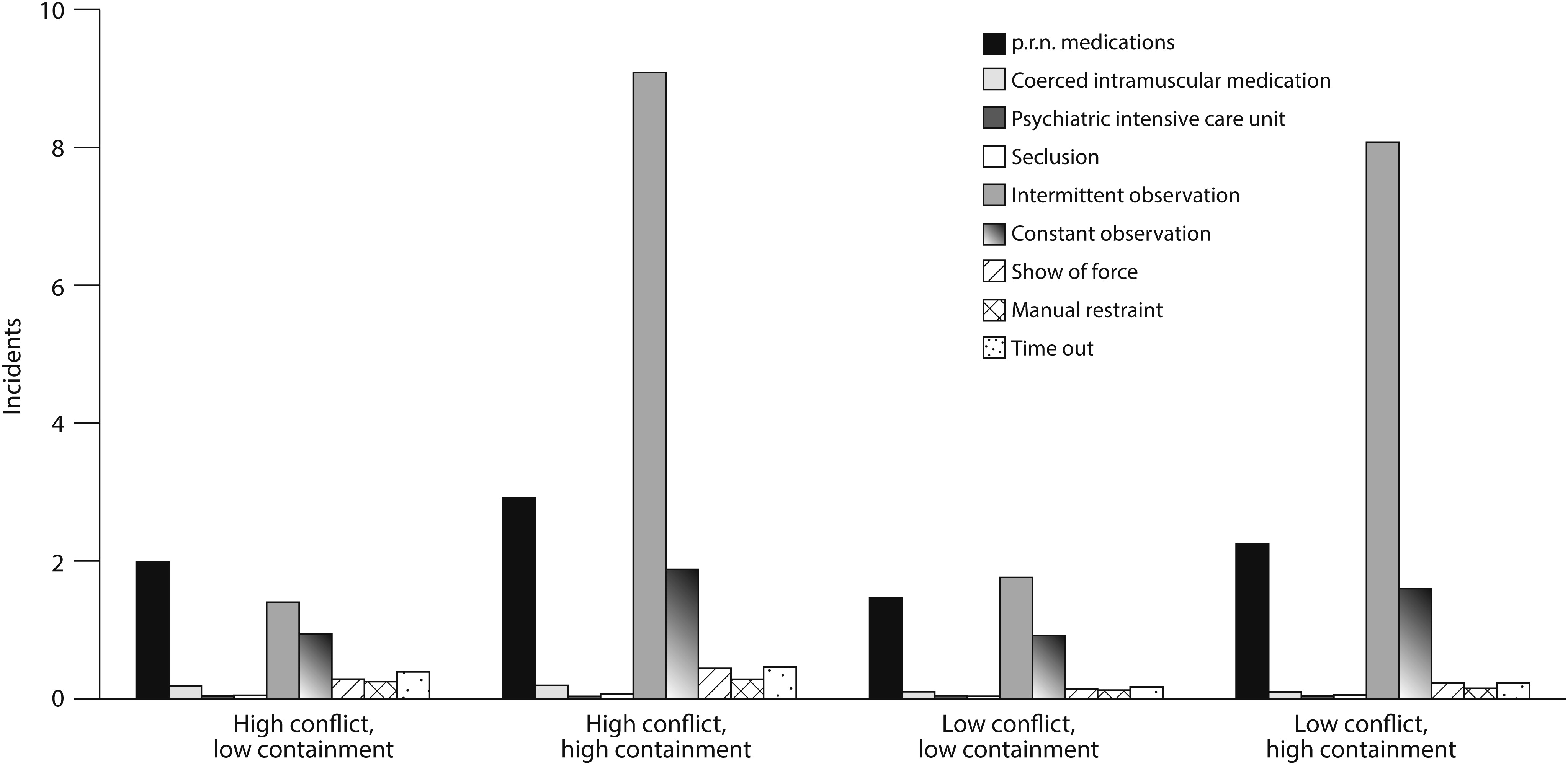

Mean rates of different types of conflict and containment event by type of ward are shown in

Figures 3 and

4. The rank order by frequency of different types of conflict events among the four categories did not vary; however, rule breaking exceeded other types of conflict by a much greater factor in the high-conflict, low-containment wards than in any other type. Rule breaking includes a range of noncompliant and low-level disruptive behaviors, including smoking in a no smoking area or refusal to get up or go to bed, see workers, eat, drink, or wash. Similarly, the rank order of frequency of type of containment did not vary by the type of ward. However, it is apparent that the greater use of containment on wards with high levels of containment was primarily explained by the use of intermittent special observation, which was more frequent by a factor of about four in high-containment wards. All other forms of containment varied by a factor of about 1.7 to 2.0.

Discussion

Previous analysis of the same data set with multiple regression yielded some similar results, especially the overall differences reported here between high-conflict, high-containment and low-conflict, low-containment wards (

6). Social deprivation and formal detention were associated with higher conflict rates, and good ward organization was associated with lower containment rates. However in that previous analysis, no effect for ward size was found.

Exploration of the results by individual quadrant is, perhaps, more illuminating (

Figure 2). The association of high-conflict, high-containment wards with high numbers of temporary and unqualified staff suggests that mobilizing large numbers of such workers does not produce a safer and less coercive ward. It is also striking that although patient characteristics accounted for some of the differences between these wards and wards in the low-conflict, low-containment category, the structure of the ward and its activities, as measured by the WAS, also played a significant part, implying that efforts to increase order and organization and program clarity could move some high-conflict, high-containment wards toward or into the low-conflict, low-containment category.

The low-conflict, low-containment wards had fewer common overall differences with the other categories, instead being different from each in specific ways. This may imply that there are different ways to achieve low rates of conflict and containment. Some differences, however, are not amenable to change. Wards cannot change the social deprivation of the areas they serve, although it may be possible to positively influence the rates of formal detention (

15).

The high-conflict, low-containment and the low-conflict, high-containment wards challenged the idea of a close connection between rates of conflict and containment, and their features, perhaps, are particularly illuminating. The high-conflict, low-containment wards demonstrated a worrisome connection between poor physical environments, social deprivation, and higher proportions of patients with schizophrenia and staff and patients from ethnic minority groups. This finding, perhaps, indicates that in some areas, the “inverse care law” of Hart (

16) still holds sway, with the greatest need being matched with the poorest service provision. We have reported before on connections between rates of conflict and containment and the characteristics and distribution of staff (

17).

The existence of wards of this type shows that in the face of high levels of conflict, some wards managed to use low rates of containment. It is unlikely that this combination represented staff who were laissez-faire with patients or whose wards were out of control in some sense, for if either were the case, order and organization and program clarity would have been significantly lower than on other wards. Therefore, the findings suggest that such wards employed a low-confrontation, nonpunitive philosophy of care, an interpretation supported by the finding that they had excessively high rates of general rule breaking compared with other forms of conflict. Perhaps, in addition, greater numbers of male staff and staff from ethnic minority groups allowed a more confident and tolerant response to challenging patient behavior. These two characteristics demarcated the difference between high-conflict, low-containment and high-conflict, high-containment wards.

The other quadrant of interest represents wards that had low conflict rates but used high levels of containment. Compared with the other categories, low-conflict, high-containment wards were primarily large wards (in terms of patient numbers), although they did not have significantly different numbers of staff per bed. The high levels of containment suggested that the staff responded to the higher patient numbers with a harsher regime of containment.

The finding that wards with high and low rates of containment varied more in use of intermittent observation (regular checks on patients) than of any other containment practice is curious. Intermittent observation has received little research attention. We know that it is approved by more patients than any other containment method (

18), is associated with lower rates of self-harm (

19), is in a dynamic relationship with other forms of patient surveillance (

20), and can be successful in preventing suicide (

21). Some wards may place all patients on intermittent observation for a period following admission as a routine practice. Intermittent observation is also likely to be one of the easiest forms of containment for staff to initiate and carry out, and it is the least likely to be objected to by patients. Thus it might be more responsive to the drivers of all containment methods as a whole.

Alternatively, the wide variance in rates of intermittent observation, to some degree. might be an artifact of the way incidents of intermittent observation were counted. End-of-shift checklists indicated the numbers of patients on intermittent observation for all or part of the shift. Thus patients on intermittent observation for protracted periods of several days would produce one count for each shift during the period of observation. However, it remains a moot point whether one patient on intermittent observation for ten nursing shifts represents the same quantity of containment as ten patients on intermittent observation for one shift. Had periods of observation initiated been counted instead, the variance in intermittent observation rates may have been less than or comparable to rates of other forms of containment in this study.

Previous analyses of this data set at the shift level have shown associations between higher numbers of qualified nursing staff on duty and more conflict and containment (

22), although the effects identified were small. This analysis at the ward level suggests that other aspects of nurse staffing may be more important, specifically the gender mix, the comparative ethnic balance of the staff team and the patient group, and the use of temporary and unqualified staff.

A key limitation of this study was the cross-sectional nature of the data set. Therefore, the direction of causality in relation to any of the significant associations reported in this study could not be ascertained.

Conclusions

The evaluation of inpatient units by combined level of conflict and containment provides insights not appreciable when linear regression methods are utilized. The differences between units found in the analysis presented here were based on combined levels of conflict and containment and suggested that conventional one-dimensional linear analysis overlooks the complex interplay of variables that contribute to a ward’s experience with conflict and containment.

Our previous research has investigated how conflict and containment might be reduced to minimum levels. Thus the wards with low conflict and low containment in this study represent an ideal type to which other wards should aspire. It is interesting, therefore, that the low-conflict, low-containment wards were the most coherent group, yet they were also the least distinguishable from the other categories of ward in terms of patient characteristics and organizational features. These findings point to the considerable challenges faced by services that wish to act to reduce levels of conflict and containment, especially large, relatively run-down wards in areas of deprivation. Maintaining a workforce of permanent and qualified staff would appear to be a high priority because it would facilitate improving the structure and clarity of the ward regime, which is also necessary. The use of large numbers of temporary and unqualified staff is clearly not an effective solution. Good-quality, secure staffing and decent physical environments are in the hands of management rather than the nurses on the wards, indicating that to some degree, low conflict and containment are outcomes of effective hospital management.

Rates of formal detention in hospital might be reduced by interventions in the community (

15), also producing some impact on the wards. Social deprivation and high rates of schizophrenia require political action and social change on a widespread level. However, the results also showed that even in the face of high rates of conflict, low levels of containment, including seclusion, coerced medication, and manual restraint, can also be achieved. They also showed that good structure and organization on the ward have an impact, and these matters are in the hands of nursing staff.