Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is associated with increased utilization of mental health care and general medical care services (

1,

2). The greater use of treatment among persons with PTSD may be explained by the need to treat the disorder, but it may be due to associations between PTSD and other mental and general medical disorders (

3–

5). For example, PTSD is strongly associated with depression, anxiety disorders, somatization, and substance use disorder (

6,

7). Also, PTSD is associated with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and coronary heart disease (

8–

11).

Results

According to their PCL scores, 79 (12%) of the 635 participants fulfilled the

DSM-IV symptom criteria B, C, and D for PTSD. In addition, 97 (15%) participants fulfilled our criteria for partial PTSD.

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics and tsunami exposure among participants with PTSD, partial PTSD, and no PTSD. Participants with PTSD and partial PTSD included a higher proportion of women, were less likely to be married or cohabiting, and reported more severe exposure to the tsunami than participants without PTSD.

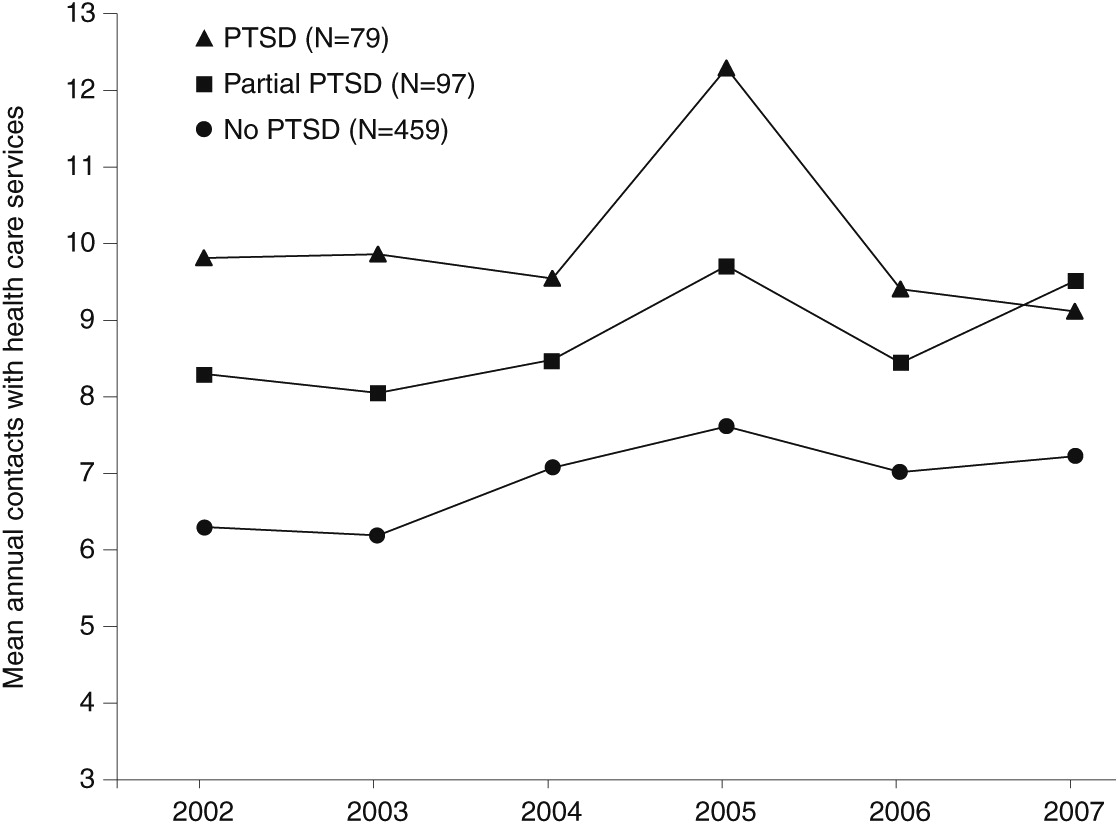

Figure 1 shows the annual number of contacts with health care services before and after the tsunami among participants with PTSD, partial PTSD, or no PTSD. Compared with participants with no PTSD, participants with PTSD or partial PTSD had significantly more annual contacts during the three-year periods before and after the tsunami

(Table 2). Annual contacts before and after the tsunami among participants with PTSD and partial PTSD did not differ significantly. Overall, the annual number of contacts with health care services increased .76 (9%) during the three years after the disaster compared with the three years before the disaster (t=4.19, p<.001). The increase in annual contacts for all health care services did not differ among the groups (

Table 2).

The increase in annual contacts with health care services was most prominent during 2005, the year after the disaster (

Figure 1). We performed post hoc tests to examine whether there were differences among the groups in the extent to which health care service contacts increased from the three years before the disaster to 2005. The annual number of health care service contacts increased by 2.55 (26%) in the group with PTSD (t=3.54, p<.01), by 1.43 (17%) in the group with partial PTSD, and by 1.09 (17%) in the group with no PTSD (t=4.13, p<.001). The increase in health care service utilization did not differ significantly among the groups.

Table 2 shows that GP contacts constituted a majority of health care service contacts among all groups. Contacts with GPs varied more among the groups than visits for any other health care service. Contacts with psychologists, psychiatrists, and members of other medical specialties constituted only a minor part of the total use of health care services. Overall, contacts with GPs (t=3.34, p<.001), psychologists (t=5.03, p<.001), and members of other medical specialties (t=2.28, p<.05) showed a significant increase after the disaster (

Table 2). Use of a psychologist was the only health care service that increased significantly more after the disaster among participants with PTSD and partial PTSD than among participants with no PTSD (F=10.96, p=.001), but even among participants with PTSD and partial PTSD the increase was rather small (.2±.6 contacts).

Table 3 shows the association between predisaster use of health care services and prevalence of postdisaster PTSD and partial PTSD and severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms. The prevalence of PTSD was considerably higher in the quartile with the highest number of predisaster health care service contacts (19%) compared with the quartile with the lowest number of health care service contacts (6%). Also, the severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms was significantly associated with predisaster use of health care services.

Table 4 shows the association between severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms ten months after the disaster and the annual number of contacts with health care services in 2006–2007. In bivariate analysis, symptom severity was significantly associated with subsequent use of health care services (model 1). The association remained significant when the analysis was adjusted for sociodemographic variables (model 2). When adjusted for predisaster use of health care services, however, the association between severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms and subsequent use of health care services disappeared (model 3).

Discussion

In our study of a sample of Danish tourists who experienced the Southeast Asian tsunami in 2004, unadjusted analyses showed a relatively strong association between PTSD, partial PTSD, and severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms and use of health care services outside hospitals after the disaster. However, participants with PTSD and partial PTSD had used health care services before the tsunami more frequently than participants with no PTSD. Also, the increase in health care service use before and after the disaster was not significantly higher among participants with PTSD or partial PTSD compared with those with no PTSD. When predisaster use of health care services was taken into consideration, the association between severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms and subsequent use of health care services disappeared.

The ten-month prevalence of PTSD (12%) among survivors who fulfilled

DSM-IV PTSD criterion A1 (severely disaster exposed) is consistent with similar reports in the literature (

23). The level of health care service utilization by all participants was consistent with rates of utilization in the general Danish population (

www.sst.dk/publ/tidsskrifter/nyetal/pdf/2005/02_05.pdf [in Danish]). Also, the finding that PTSD, partial PTSD, and severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms were associated with higher use of health care services is in concert with previous research involving community samples (

24), combat veterans (

3,

5), residents of New York City after the World Trade Center disaster (

25), survivors of other man-made (

26) and natural disasters (

27), and even Scandinavian survivors of the 2004 tsunami (

28).

To our knowledge, the association between PTSD and subsequent use of health care services has not previously been adjusted for preexisting use of health care services. Our finding that postdisaster health care service utilization was largely predicted by predisaster health care service utilization and that it was hardly affected by the onset of posttraumatic stress symptoms itself raises important questions about the consequences of traumatic stress, especially from a long-term perspective.

First, our findings prompt questions about previous assertions that the presence of PTSD is the causal factor leading to high health care service utilization (

2,

29), particularly after one or more years have passed since the trauma. Another alternative explanation is that survivors with PTSD have higher use of health care services even before symptom onset and that PTSD symptoms themselves are not responsible for health care service utilization. Survivors with PTSD may neglect seeking help for their posttraumatic stress (

25,

30), they may have limited access to adequate treatment in the health care system (

31), or their help seeking may replace, or be integrated into, health care consultations they would otherwise carry out. However, neglect of symptoms or limited access to health care was not supported by self-reports of health seeking in the Danish tsunami cohort. For example, ten months after the disaster, 40% of the repatriated Danish tourists, including those who had not been exposed to the tsunami, reported having consulted with their general practitioner for disaster-related problems (

28). This treatment-seeking behavior was strongly associated with posttraumatic stress. It is possible, however, that treatment seeking for PTSD may have been strongly limited in the number of consultations and primarily occurred in the close aftermath of the disaster.

Second, our findings raise questions about previous assertions that psychological trauma explains the association between PTSD and other mental and general medical conditions (

32). An alternative explanation is that survivors who develop PTSD have a preexisting vulnerability for mental and general medical conditions (

33), as suggested by the higher use of health care services before the tsunami. Evidence for this hypothesis includes prospective studies that have identified preexisting mental and general medical conditions (

34), neuroticism (

35,

36) and low cognitive ability (

37) as risk factors for PTSD. Thus the frequent use of health care services among individuals with PTSD, as well as their increased vulnerability for other mental and general medical disorders, may be primarily a result of preexisting health conditions, low cognitive functioning, and ineffective coping strategies.

Virtually the entire population of Danes who were in Southeast Asia during the 2004 tsunami was asked to participate in our study, reducing sample selection bias. Furthermore, the Danish population is serviced by national health care that provides relatively equal access to care. Therefore, it is possible to evaluate the relation between PTSD and health care service utilization without considering economic factors. In nations with multipayer health incurrence, based on a mixture of public and private insurance programs, the role of economic factors in use of health care services could not be ignored.

Limitations of the study included a relatively low response rate. However, according to a study of nonresponders in a comparable cohort of Norwegian tsunami survivors who had a similar response rate (

38), nonresponders were less likely than responders to have been in a place directly affected by the tsunami and to have fulfilled

DSM-IV PTSD criterion A1. Furthermore, in this study, responders and nonresponders were similar with regard to age (

15) and predisaster use of health care outside hospitals. Also, participants were similar to the general Danish population with regard to education and employment and included women and men of all ages.

Whether participants fulfilled

DSM-IV PTSD criterion A1 was assessed by retrospective self-report, which may have been distorted by memory bias (

39). To minimize such bias, we defined exposure on the basis of what may be considered objective events. The use of a single, self-report questionnaire to measure participants’ symptoms ten months after the disaster was also a limitation. Although the PCL is based on the

DSM-IV symptom criteria, it cannot substitute for more comprehensive clinical interviews.

Our use of prospective national register data provided a measure of health care service utilization outside hospitals that is unaffected by possible recall and information biases that typically influence self-reports. Also, the equal accessibility of commonly acknowledged treatment minimized possible selection biases. The use of GPs is a sensitive measure of individual use of both social and health care services, given that the GP is a gatekeeper to other health care services as well as the physician who bears responsibility for communicating to social authorities.

Another limitation was entering utilization of health care services in the second and third years after the disaster as a variable in our predictive regression model. During this time frame, some survivors may have recovered from PTSD, resulting in reduced health care use. However, epidemiological research suggests that one-third of individuals who develop acute PTSD remain symptomatic for six years or longer (

6). Similarly, 43% of the Danish tsunami survivors who had PTSD or partial PTSD ten months after the disaster were still symptomatic during a follow-up survey conducted two-and-one-half years after the disaster, indicating that a majority still suffered from disaster-related health problems (

40).