People with mental illnesses are overrepresented in the criminal justice system in the United States. This includes jails and prisons as well as probation or parole supervision in the community (

1–

7). These settings are rarely appropriate for psychiatric treatment (

8). For people with mental illnesses—who face inordinate poverty, unemployment, crime, victimization, family breakdown, homelessness, substance use, general health problems, and stigma (

9–

11)—contact with the criminal justice system can exacerbate social marginalization, disrupt treatment and linkage to service systems, or represent the first occasion for treatment. For the corrections system, which was not designed or equipped to provide mental health services, the high prevalence of people with mental illnesses has capacity, budgetary, and staffing ramifications; high numbers of people with mental illnesses affect the provision of constitutionally mandated treatment “inside the walls,” community transition planning and reentry services, and community corrections caseload. More generally, mental illness (and co-occurring substance use disorders) represents a substantial component of the public health burden of mass incarceration—a phenomenon where structural inequalities in race, social class, crime, health, and social services intersect.

Among this handful, two reports by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (

2,

3) have been cited at least 1,100 times, according to a recent query of Google Scholar. These reports used self-report surveys and defined mental illnesses as a current mental or emotional condition, a prior overnight stay in a “mental hospital,” or endorsement of symptoms of mental disorders in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (

DSM) (

13). Prevalence estimates were three to 12 times higher than in community samples, reaching as high as 64%.

Given the role that such prevalence estimates play in framing programs and policies, past research has sought to inventory and integrate findings from a broader sampling of studies that used more robust case ascertainment strategies. At least seven prior systematic (

14–

18) and nonsystematic (

19,

20) literature reviews or meta-analyses have been published in the past two decades. These reviews, however, tend to include studies that predate the policies that would contribute to the present program of mass incarceration (the “War on Drugs” and “three strikes” laws [

21]), include international findings, combine jail and prison estimates, or focus on a single disorder or on few disorders. The most recent is an important meta-analysis, based on pooled jail and prison data, that provides summary estimates for the prevalence of psychotic disorders and major depression among 33,588 incarcerated individuals worldwide (

14). This analysis puts mental illness and incarceration in a global context and addresses high levels of heterogeneity between studies with sophisticated techniques.

In the United States, however, the criminal justice system and mass incarceration are institutions with unique racialized, economic, and political contexts that make cross-country comparisons difficult. Furthermore, prisons and jails are functionally discrete, and the two should not be conflated by researchers, as they entail different mitigation strategies from a public health perspective. [A table available in the online

data supplement to this article outlines key differences between jails and prisons.] The purpose of this report is therefore to summarize and synthesize research on the prevalence of mental illnesses in U.S. state prisons. This systematic review is intended to add to the existing body of literature by being both more inclusive and restrictive than prior reviews—allowing for studies not necessarily focused on mental illness and limiting review to state prisons in the United States. This review also explores methodological issues that continue to make obtaining accurate prevalence estimates a challenge for researchers and policy makers alike.

Methods

A systematic review of the scholarly literature was conducted to identify studies that presented prevalence estimates of mental illnesses in prisons. Articles were included if they were published in peer-reviewed, English-language journals between January 1989 and December 2013, focused on U.S. state prisons, reported prevalence estimates of diagnoses or symptoms of

DSM axis I disorders, and clearly identified the denominator for prevalence proportions. Articles were excluded if they did not present original data; focused solely on axis II disorders, youths, jails, or foreign prisons; selected samples only of people with mental illnesses or substance use disorders; presented only combined jail and prison prevalence estimates; did not present prevalence estimates (for example, presented only mean scale scores or odds ratios for disorders); or the denominator for prevalence estimates was not apparent. Samples selected on the basis of substance use were excluded given the high rates at which substance use disorders co-occur with mental illnesses among incarcerated individuals (

1,

22), which would therefore not provide good estimates of mental illnesses per se. A review of the prevalence of substance use disorders in prisons was beyond the scope of this report.

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, the National Criminal Justice Reference Service, Social Services Abstracts, Social Work Abstracts, and Sociological Abstracts were searched. For MEDLINE and PsycINFO, combinations of the following medical subject headings (MeSH) were used: mental disorders, mental health, prevalence, incidence, epidemiology, psychotropic drugs, drug therapy, prisons, and prisoners. For the remaining databases, similar keyword combinations, including axis I disorder terms, were searched.

All articles were uploaded into EndNote×4 software. Duplicate entries were identified with the software’s deduplication function, and entries were then sorted alphabetically by title to visually identify any missed duplicates. The initial search yielded 3,670 nonduplicated articles. Based on titles and abstracts, 3,388 articles did not meet inclusion criteria and were excluded. All articles published between January 1989 and December 2013 contained in previous reviews or meta-analyses were captured in this search. Full texts of the 282 remaining articles were reviewed, and an additional 254 studies were rejected based on exclusion criteria outlined above, one of which (

23) was excluded because it re-reported findings from an earlier study included below. Twenty-eight articles were thus included in the review. In rare cases, prevalence proportions were recalculated for this review when a more appropriate denominator was reported (for example, the general facility population rather than a subpopulation). Approximations for summary prevalence estimates were calculated by taking weighted means of all reported diagnoses (any mental illnesses) and of major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic disorder (serious mental illnesses). Figures were created in R, version 3.1, with the ggplot2 package (

24).

Results

Researchers characterized the prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons in three main ways: as a broad category of unspecified psychiatric disability, or “mental health problems,” resulting in four studies (

Table 1) (

25–

28); as a diagnosis of a

DSM-defined psychiatric disorder, which yielded 19 studies (

Table 2) (

29–

47); and as cut points on scales of symptoms or psychiatric distress, which yielded five studies (

Table 3) (

48–

52).

Tables 1–

3 also present key information on each of the 28 studies in addition to prevalence estimates: facility type (single prison versus all prisons in a given state), target sample (men, women, general prison population, or some special prison subpopulation), method of case ascertainment (from case files or a particular screening or diagnostic instrument), diagnostic classification system, and current versus lifetime prevalence. [Expanded versions of the tables are available in the online

data supplement.] Of the 19 studies that presented prevalence estimates of

DSM diagnoses, five presented estimates of diagnosis groupings that could not be disaggregated (see supplemental Table 3).

Estimates of the current and lifetime prevalence of mental illnesses in state prisons varied widely. For example, in this review, estimates for current major depression ranged from 9% to 29%; for bipolar disorder, from 5.5% to 16.1%; for panic disorder, from 1% (women) to 5.5% (men and women) to 6.8% (men); and for schizophrenia, from 2% to 6.5%.

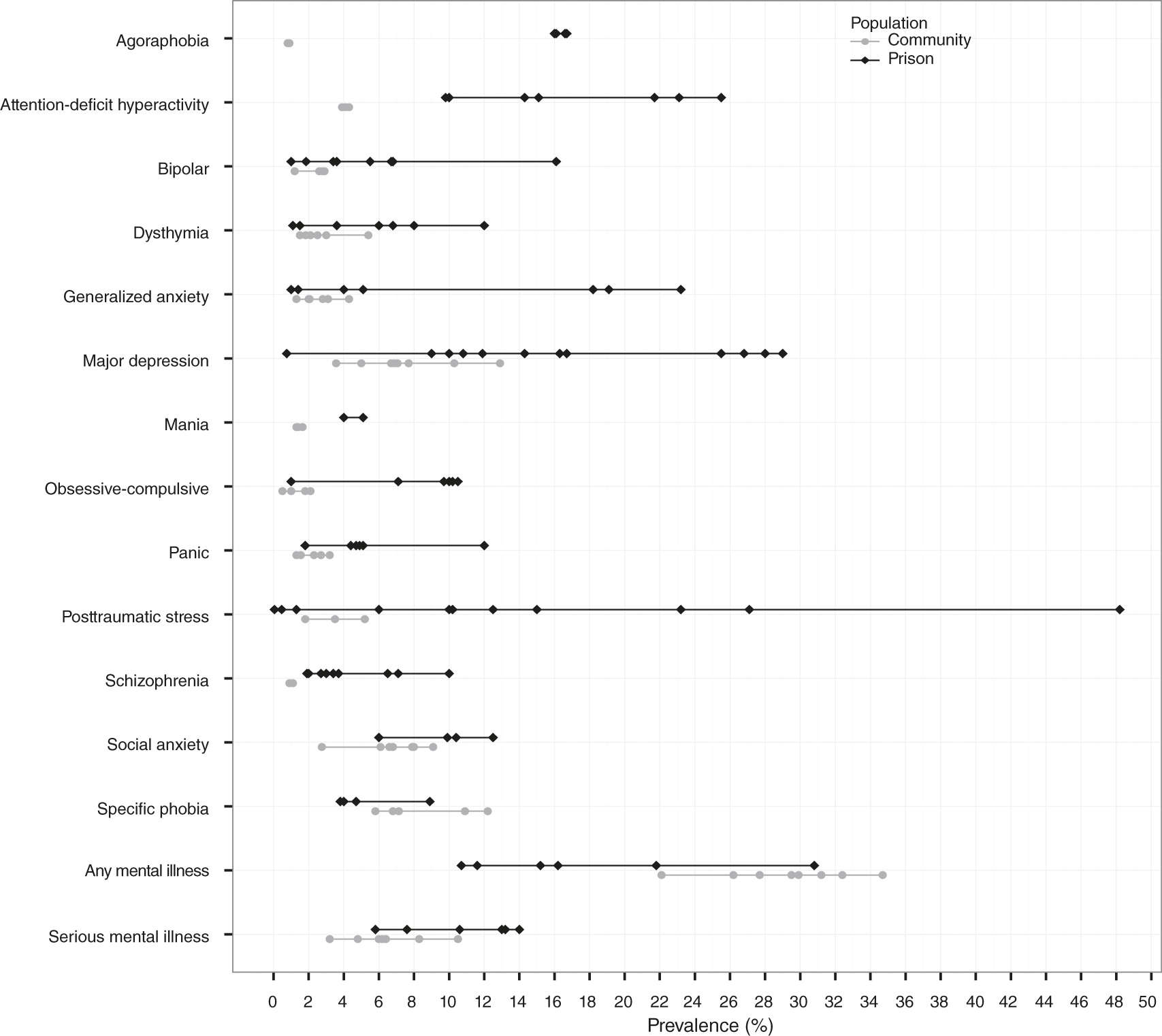

Figure 1 summarizes current prevalence estimates for all studies that presented findings for psychiatric diagnoses (

Table 2 and supplemental Table 3).

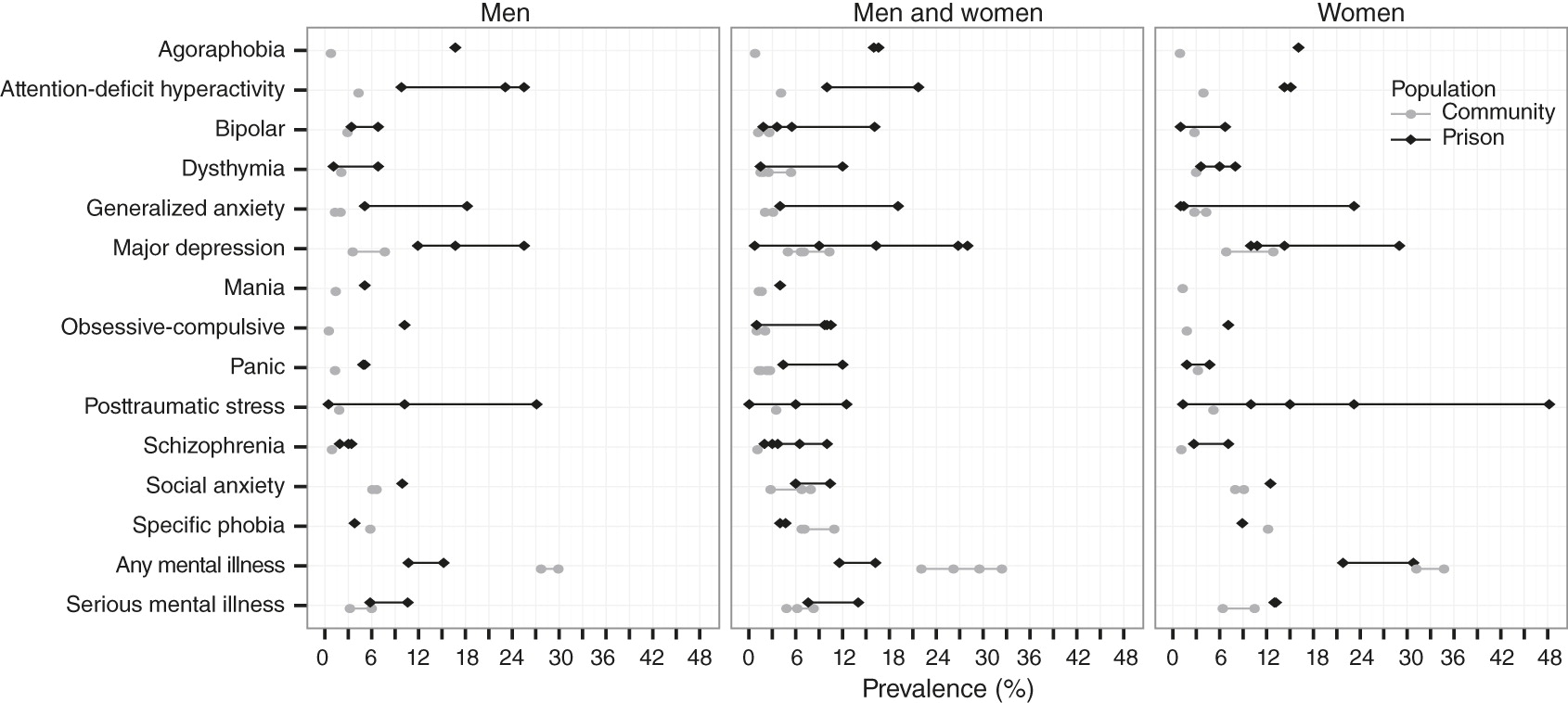

Figure 2 separates the results from

Table 2 and supplemental Table 3 by studies that presented findings on men, men and women, and women, respectively. As a point of comparison,

Figures 1 and

2 also display the range of prevalence estimates for select disorders from major community surveys of mental illnesses: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey (

53–

55), the National Comorbidity Survey (

56,

57), the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (

58–

60), the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (

61–

64), and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (

65). For example, in

Figure 1, seven studies provided prevalence estimates for having attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in prison, which ranged from approximately 10% to 25%. It is clear from

Figures 1 and

2 that community prevalence estimates tended to fall near or below the low end of the range of prison prevalence estimates, and the range of prevalence estimates tended to be greater in prisons than in the community.

Figure 1 also shows prevalence estimates for any mental illness and serious mental illness (

57,

65–

67). These are shown with estimates from community surveys for comparison. Estimates of any mental illness were calculated by taking weighted means from

Table 2 and supplemental Table 3 of all disorder diagnoses. It must be noted that, although reviewed studies do not include diagnoses of substance use disorders, it was not possible to exclude these disorders from most community comparisons of any mental illnesses. Estimates of serious mental illness were calculated by taking weighted means from

Table 2 and supplemental Table 3 of major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic disorders. Because one study (

29) was much larger (N=170,215) than the others, it exerted appreciable influence on the weighted means; thus weighted means for any mental illness and serious mental illness were also calculated after excluding this study to provide the high end of the range for these categories in

Figures 1 and

2. Because no measure of functional impairment was available in most studies and definitions of serious mental illness varied across surveys, caution is warranted in making inferences from these comparisons.

Several of the studies reviewed are notable for strong methodology. In one study (

41), researchers used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID) (

68) and found prevalence estimates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (15%), major depression (10%), and dysthymia (8%) among incarcerated women that were mostly higher than estimates for the general population. Another study (

47), however, used the SCID and clinician-administered assessment interviews and found the prevalence of PTSD among incarcerated women to be 48.2%. Another study (

42) used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (

69) with reinterviews by clinicians and found prevalence estimates of major depression (10.8%), generalized anxiety disorder (1.4%), and panic disorder (4.7%) among incarcerated women that were similar to or higher than those in the general population. Using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (

70) followed by clinical interviews, another study (

30) found prevalence estimates of major depression among incarcerated women to be 29%.

Discussion

This systematic review summarized 28 studies, published between January 1989 and December 2013, of the prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons in 16 states. As a result of inclusive search criteria, this review contains data on the prevalence of mental illnesses among incarcerated subpopulations such as HIV-positive women, individuals aged 55 and older, suicide attempters, and persons under administrative segregation (that is, separated from other inmates for various reasons). This review presents a detailed summary of key study characteristics that may be of interest to researchers, policy makers, and practitioners. These details are likely implicated in the overall inconsistency in findings. Nonetheless, reviewed studies generally confirm what researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and advocates have long understood: the current and lifetime prevalence of numerous mental illnesses is higher among incarcerated populations than in nonincarcerated populations, sometimes by large margins. Yet, the wide variation in prevalence found among even the more robust studies reviewed here warrants caution against generalizations from any single study. Furthermore, with the heterogeneity in samples, states, facilities, study designs, and diagnostic instruments represented in this review, drawing anything more than broad conclusions about the veracity of particular prevalence estimates relative to others would be inappropriate. For example, studies that used validated instruments followed by clinical interviews were likely to be more robust than those that used only correctional health records.

Explaining the lack of consistency among prevalence estimates is no easy task; however, two likely contributing factors warrant discussion here. These can be characterized as issues of measurement and selection. Measurement issues are artifacts of the research process and can be inferred from the characteristics of the studies summarized in this review, whereas selection issues represent “real” phenomena about which one can only speculate based on the data presented here.

In regard to measurement, methodological differences in the definition of mental illness, sampling strategies, and case ascertainment strategies may explain a significant amount of the variation across studies. Measurement differences may arise from a divergence in the disciplinary orientations of researchers and the constraints on access and other resources inherent in conducting research in institutions that are organized for separation, security, and control. Researchers with a forensic orientation, for example, may be less interested than community mental health researchers in strict adherence to

DSM-IV diagnostic criteria because the primary concern of forensically oriented researchers may be in identifying administrative needs and population management risks. Researchers may be granted limited access to a single correctional institution or to records for an entire statewide system that contain only rough proxies for mental disorders. During primary data collection, intake procedures may limit the time that can be spent on screening and assessment, which may limit the type of personnel (lay versus clinician) and instruments or scales (screens versus structured diagnostic interviews) that can be used. Indeed, in this review, over a dozen different case ascertainment strategies are represented, each with its own strengths and weaknesses in regard to diagnostic reliability and validity (

71). Furthermore, these instruments were based on at least five variations of psychiatric nosology, from

DSM-III through

DSM-IV-TR and the

ICD-10.

Another source of variation in prevalence estimates may stem from differential “selection into prison,” which can be conceptualized as the real forces that influence the “base” or “source” populations that contribute to the composition of prison populations in different jurisdictions. These selection forces are likely determined by myriad macro- and meso-level factors beyond individuals’ propensity for arrest or crime. These include, but are not limited to, the demographic composition of state populations more broadly, political-economic arrangements and trends, criminal codes (such as those that concern drug policies), corrections policies, mental health and substance abuse treatment policies and availability of services, housing policies, policing strategies, and so on.

Of particular interest for criminal justice and mental health policy makers and practitioners is the question of whether increased access to treatment services would reduce the number of people with mental illnesses (and co-occurring substance use disorders) in corrections settings (

72). If one accepts the logic that lack of treatment causes people with mental illnesses to make contact with prisons, then states that (on average) provide more and better treatment for co-occurring disorders should have a lower prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons. This is an empirical question that was beyond the scope of this review. Nonetheless, two aspects of this selection issue deserve consideration. First, state prison populations are less “local” than county or municipal jail populations, because state prisons typically receive individuals from across a state. If mental health and substance abuse treatment access and utilization affect the prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons, prison composition is likely to reflect the average impact of these services across numerous jurisdictions within a state. Second, most people in the United States with serious mental illnesses, including substance use disorders, do not receive treatment (

73–

75). For these individuals, contact with the criminal justice system may represent the first occasion for any treatment services (

8). Given within- and between-state differences in service quality and access (across urban and rural areas, for example), the impact of these services—or lack thereof—on the prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons may not be straightforward.

One limitation of this review is that it did not include studies that used proxy indicators of mental illnesses, such as corrections department expenditures on medication or clinical staffing. Although treatment is an imperfect proxy for the presence of mental illnesses, in that prevalence estimates based on treatment reflect well-documented disparities in access and utilization (

74–

76), a systematic review of this literature would nonetheless be worthwhile to draw special attention to budgetary issues. Another limitation is that this review did not include gray literature, because the review was designed to focus on peer-reviewed publications. With 50 states, at least 50 departments of corrections with varying degrees of data unification and reporting standards, and varying numbers of prisons per state, systematically obtaining unpublished or low-circulation reports from these agencies and facilities was beyond the scope of this review. Such a project clearly would be a crucial component of future research.

Reasons for the high prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons have been explored in depth elsewhere (

8,

10,

77–

81). In response, specialized programs have been in effect for over a decade that are designed to divert people with mental illnesses from contact with law enforcement, courts, and corrections to the community; to improve reentry after incarceration; and to reduce recidivism (

82–

86). Despite these efforts, the prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons remains high. Our ability to accurately measure the impact of such programs, in addition to changes in more fundamental causes of the prevalence of mental illnesses in prisons (such as drug policies), depends largely on the sorts of estimates summarized in this review. Also of interest to policy makers and practitioners is the fact that most of the roughly 2.3 million incarcerated individuals in the United States (

87) will be released, contributing to the approximately 4.8 million individuals—a majority of the U.S. corrections population—who reside in the community on probation and parole (

88). About 43% of these individuals will be detained again within three years (

89). As such, accurately measuring the prevalence of mental illnesses “inside the walls” is essential for community corrections planning. Given the existence of brief, well-validated instruments that screen for mental illnesses, such as the Brief Jail Mental Health Screen (

90), K6 (

67), and Correctional Mental Health Screen (

91), reporting standards for routine assessments upon intake are clearly feasible. Even in the absence of such standards, prison administrators, working in collaboration with mental health policy makers and practitioners, can (at relatively low cost) calibrate such screening instruments to their populations and begin collecting valid and reliable prevalence estimates.