Individuals maturing from adolescence to adulthood, referred to as young or emerging adults (

1) or transition-age youths (

2), undergo rapid legal and social status changes. Health care coverage is essential for young adults with chronic illnesses (

1,

3), especially those with serious mental health conditions, who often need a broad array of mental health, substance abuse, and medical treatments and rehabilitation services (

4). However, in 2008 in the United States, 8.7 million persons ages 19 to 29 (19%) were uninsured and another 4.6 million (10%) were enrolled in Medicaid (

5). Medicaid enrollment increases access to services and improves self-assessed somatic and mental health (

6). Moreover, in contrast to many private insurers, Medicaid often covers the rehabilitative and supportive services that young adults with mental illness need, such as educational and employment supports (

7). However, many low-income, young adults with serious mental health conditions are at risk of disruptions in Medicaid coverage.

Medicaid is offered principally to individuals made vulnerable by having low income or disability (

5,

8,

9). Children predominate in Medicaid populations as a consequence of preferential eligibility under federal law (

9). However, among Medicaid-covered individuals who are approaching legal adulthood, coverage is frequently withdrawn or reduced after a redetermination process at age 18 (

9,

10). Among Medicaid-enrolled 16-year-old mental health services users, disenrollment was shown to increase sharply at ages 18 and 19, with about half of females and two-thirds of males experiencing at least six months of disenrollment by age 19 (

11). In addition, some states require age-based changes in enrollment categories at age 21 (for example, foster care coverage [

12]). Moreover, gaps in insurance coverage (public or private) significantly diminish access to needed health care (

13,

14).

This study examined predictors of Medicaid disenrollment among young adults (ages 18 to 26) during the first year after discharge from inpatient mental health care. Information on disenrollment risk factors could be used to design enrollment supports for vulnerable young adults. The postdischarge year is a period of elevated suicide risk (

15,

16), and the risk is elevated further by discontinuity in outpatient care (

17). Continuous Medicaid coverage may be an important prerequisite for timely postdischarge follow-up care, which research suggests reduces readmission risk (

18). We hypothesized that the likelihood of disenrollment would be greater at ages associated with Medicaid eligibility changes (

11), among males (

11,

19), among individuals not enrolled through a Medicaid disability category (

11,

19), among those with less serious psychiatric morbidity (

11), and among those without recent connection to primary care or outpatient mental health services. We also expected that use of primary care and outpatient mental health clinic services would be correlated with continued enrollment in Medicaid because such safety-net providers—for example, federally qualified health centers—are adept at and often required by law to help clients enroll in Medicaid when they are eligible (

20,

21). Finally, we hypothesized that “near poor” individuals (

22) (that is, individuals with incomes just above the poverty line) would be at increased disenrollment risk because even small income increases would render them ineligible for Medicaid (

23).

Discussion

This study used two distinct statistical methods, which considered all independent variables hierarchically (CART analysis) or simultaneously (probit analysis), to quantify individual-level correlates of future Medicaid disenrollment among young adults who were discharged from a psychiatric inpatient stay. In the sample, 32% experienced disruptions in Medicaid coverage in the year after discharge. This finding alone supports concerns about the adequacy of health care coverage during this interval of heightened risk for suicide and hospital readmission (

15,

16,

18,

24).

Although the disenrollment rate in this sample is comparable to disenrollment rates observed in general populations of child and adult Medicaid enrollees (

33), a relatively lower disenrollment rate was expected because of the multiple clinical vulnerabilities of these young adults. However, contrary to expectations, these young adults were not protected from disruptions in health care coverage. Moreover, young adults have been found to be less likely than any other age group to have private insurance (

34), suggesting that in the critical time after inpatient mental health treatment, many individuals in the sample may have had poorer access to outpatient mental health treatment than other child or adult Medicaid enrollees.

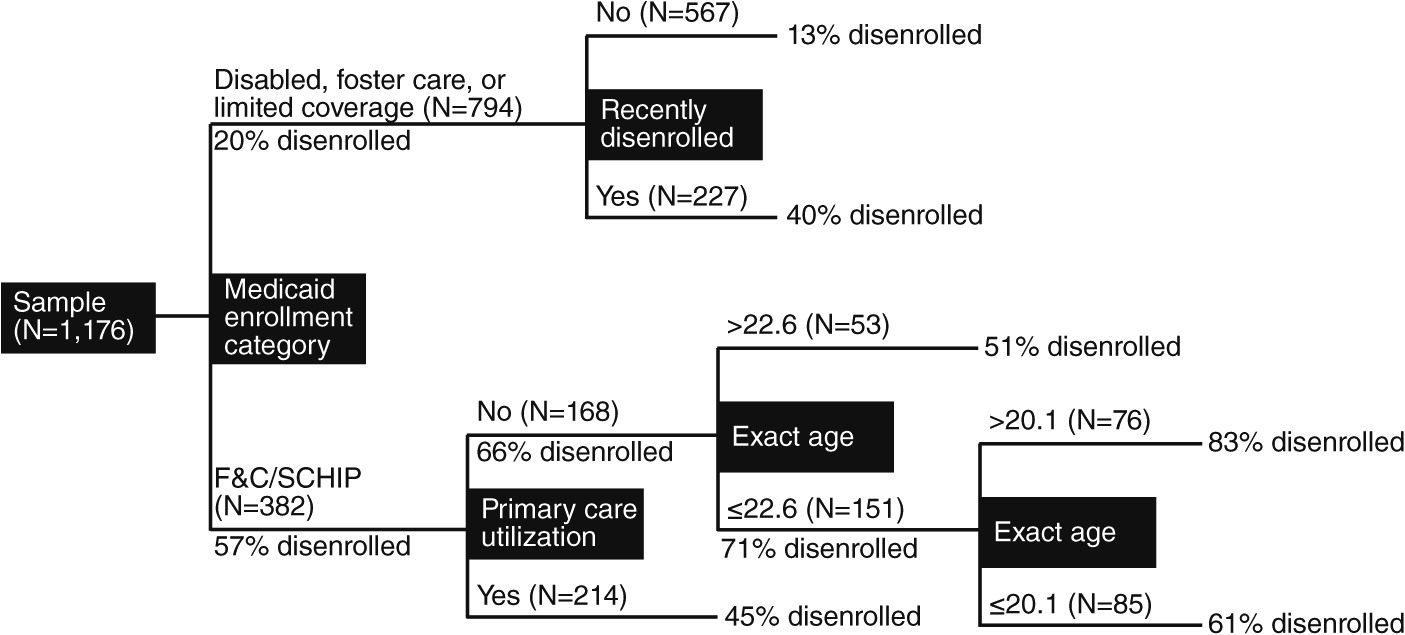

Generally, our findings confirm five of the hypothesized risk factors. Support from both the CART and probit analyses confirmed that being “nondisabled” (that is, being enrolled in the F&C/SCHIP category), being at an age at which eligibility changes (18 or 20 years old), and not having a recent connection to primary care were each correlated with disenrollment. Probit analysis also indicated greater enrollment continuity among those with greater psychiatric morbidity (that is, more inpatient days) and less continuity with relatively high incomes. Less support was found for the effect of gender or for use of outpatient mental health services in the antecedent period.

Our findings indicate that the single strongest Medicaid disenrollment risk factor was being in the F&C/SCHIP category; most of the young adults (57%) in this category were subsequently disenrolled. To qualify for this enrollment category in this age group, most would either be a parent in a low-income family or a “child” in a low-income family. This state allows “children” in low-income families to remain covered by Medicaid up to age 21 if they remain a member of their parents’ (or other guardian’s) household. Thus some would lose eligibility by turning 18 when they have left the qualifying household, and others could remain covered until their 21st birthday if they remain in the household. The high risk for those at ages 18 and 20 suggests a strong contribution of these age-defined boundaries to disenrollment. Both analyses also converged on the importance of prior disenrollment as a risk factor for subsequent disenrollment. This finding suggests that being admitted for inpatient mental health treatment does not necessarily reduce future risk of disenrollment among young adults whose enrollment in Medicaid had been inconsistent. Having either of these two characteristics (being in the F&C/SCHIP or having an enrollment gap in the antecedent period) was associated with a 51% rate of disenrollment in the postdischarge period; approximately half the population had either of these two characteristics.

Primary care utilization in the antecedent period emerged as a factor protecting individuals from disenrollment. Primary care providers may observe the individual’s risk of coverage loss and may facilitate applications for continuation. Others have observed directly or commented about the importance of primary care, including holistic care, to help persons with serious mental illness address the other health issues they typically face (

19,

35–

38).

The finding of lowered risk of disenrollment in the disabled and foster care groups and among individuals with more inpatient psychiatric days confirms that even within our clinically at-risk group, the most vulnerable individuals were less likely to be disenrolled. The surprisingly low disenrollment among foster care youths despite their “aging out” status, which was also reported by Pullmann and colleagues (

11), may be accounted for by Medicaid extensions through age 20 for those who are disabled, pregnant, parents, or medically needy (

39). For individuals in these particularly vulnerable subpopulations, case workers may undertake additional efforts to prevent disenrollment.

Pregnancy in the antecedent period also reduced disenrollment risk, consistent with previous findings in this age group (

11) and for adults in general (

20). Moreover, probit coefficients for pregnancy in the antecedent period were only slightly attenuated when the limited-coverage group was removed from the analysis. Pregnancy is a qualifying condition for limited coverage, and the limited-coverage group in this sample included 58 of the 135 pregnant women. Accordingly, it seems that any pregnancy, even if it was not the nominal Medicaid-qualifying event, resulted in more stable Medicaid enrollment. This finding suggests that new mothers or expectant women are easier to maintain in Medicaid than others, even though pregnancy-related eligibility often “expires” 60 days postpartum (

25). Continued Medicaid enrollment may be supported through women’s own motivation to keep their infant and themselves covered or if they qualify as a low-income family when infant care can make earning income challenging.

The association of higher family income with greater disenrollment suggests “temporary” eligibility that results when slight fluctuations in income or age lead to disenrollment (

23).

Overall, the findings of this study are similar to those found by Pullmann and colleagues (

11), who examined Medicaid disenrollment patterns across 7.5 years for a Mississippi Medicaid cohort of 16-year-olds with mental health service utilization. These authors also found reduced disenrollment among individuals who were enrolled through disability or foster care or who were pregnant and substantial disenrollment at ages associated with enrollment eligibility changes and among those enrolled because of low family income. Generally, the direction of the effect of other variables measured in our study and in the study by Pullman and colleagues (male gender and schizophrenia diagnosis) was similar, but it was weaker in our study. Overall, the similarity of findings is striking given the shorter duration of disenrollment and follow-up in our study and the opposite state rankings of per capita income in the two samples (in the 2007 U.S. Census, Maryland ranked fifth and Mississippi 50th).

These findings suggest that Medicaid disenrollment after an inpatient stay might be prevented by identifying young adults who are at greatest risk of disenrollment and offering them enrollment supports. Such supports would involve assistance with Medicaid reenrollment or with obtaining alternative coverage and would presumably be offered by the state Medicaid office or the public mental health authority. Given the brevity of inpatient mental health treatment and the many competing priorities before discharge, assessing disenrollment risk should happen as quickly as possible, with linkage to supports that can advocate for health care coverage and help the individual negotiate for coverage.

Beginning in 2014, implementation of Medicaid expansions and insurance exchange plans under the 2010 Affordable Care Act might be expected to reduce the risk of Medicaid disenrollment among young adults. Many states are putting in place administrative processes intended to simplify health care plan enrollment (

40,

41). Examples of these processes include using a single unified application for both Medicaid and exchange plans and designing exchange plans specifically for youths under age 21. In addition, states can make childless adults with incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty level eligible for Medicaid, at state option, with a much higher federal match than for other populations and make persons who have been uninsured for more than six months potentially eligible for federally subsidized, high-risk, state insurance plans that provide coverage for individuals with preexisting conditions.

However, there are also reasons to be skeptical of the potential effectiveness of such reforms, at least for young adults with substantial psychiatric morbidity. Each step toward preventing disenrollment or obtaining alternative health care coverage requires individuals to engage in the application process, which may be a substantial barrier for this group. Indeed, studies of health care reform in Massachusetts have found increased enrollment for young adults in Medicaid and through health care exchanges (

42,

43) but worse enrollment among adults with behavioral health problems (

44).

Several limitations should be noted. This sample comprised young adults in a single state’s Medicaid program, and the results may not generalize accurately to populations in other states, to other age groups, or to populations with different service utilization histories. In addition, the Medicaid enrollment data did not provide any information about receipt of care under private or other insurance coverage among those who disenrolled from Medicaid. However, evidence suggests that the likelihood of maintaining continuous health insurance coverage may have been quite low for these young adults, who were from low-income backgrounds and had serious mental health problems (

34). Statistical models explained only a portion of the variability in Medicaid disenrollment, with most of the variability left unexplained. Factors such as disenrollment due to imprisonment (young adulthood is the peak age for imprisonment among males) and failure to reapply, which were not captured by this database, may also have been important.