Treatment of schizophrenia entails careful consideration of the balance between symptom alleviation and avoidance of mild and serious adverse events from second-generation antipsychotics. Clearly, positive and negative symptoms have a huge impact on a patient’s life. What is less clear is the importance to the patient of relieving these symptoms (the benefits) compared with treatment side effects, such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), diabetes, or weight gain (the risks). Physicians carefully consider the importance of benefits and risks when choosing between second-generation antipsychotics or changing a patient’s regimen. Benefits of second-generation antipsychotic treatments include improvements in relapse rates; positive and negative symptoms; and functional measures, such as the Personal and Social Performance Scale. Common risks include weight gain, diabetes or metabolic syndrome, EPS, and prolactin elevation. Two additional key considerations are formulation, typically oral versus long-acting injectables (LAIs), and patient adherence. LAIs have the potential to improve outcomes when adherence has been problematic (

1).

Assessing the importance that physicians associate with various benefits and harms is valuable because these preferences influence physicians’ treatment decisions and patients’ comfort with these decisions. The preferences can be quantified with discrete-choice experiments (DCEs), which assess the relative importance of benefit and risk attributes (

2–

4). DCE is a well-accepted, validated method for assessing how respondents trade off the various properties of alternatives. Studies of schizophrenia treatment with public policy makers, consumers, families, and providers have shown that respondents value reduction of positive symptoms and improved social functioning over reduction of negative symptoms and EPS (

5). Other studies have shown that medication side effects are of greater concern to patients and their families than to clinicians (

6–

10). Therefore, our research question was “Which key benefit and risk attributes of second-generation antipsychotics do physicians trade off and consider when balancing formulation and adherence as adherence changes?”

Methods

DCEs

DCEs ask respondents a series of choice questions, requiring them to indicate which of several hypothetical treatment alternatives they most prefer or judge to be most appropriate. Treatment alternatives are defined by systematically altering the levels of various treatment outcomes or characteristics, such as benefits and risks. This approach is based on the premises that treatments are composed of a set of attributes or outcomes and that the value of a particular treatment is a function of these attributes. This approach has been used in many health care–related applications (

11–

14), with both face-to-face interviews and, increasingly, online surveys (

2,

4,

15). Analyzing the patterns of responses to the hypothetical choice questions can quantify the relative value that respondents place on each characteristic over the range of outcomes evaluated (

2,

16).

Study sample

The target sample size was 200 psychiatrists in the United States and 200 psychiatrists in the United Kingdom. Minimum sample sizes in DCEs depend on a number of criteria, including the question format, the complexity of the choice task, the desired precision of the results, and the need to conduct subgroup analyses (

17,

18). Most DCEs in health care that have included numbers of attributes and levels similar to those in this study used sample sizes between 100 and 300 respondents (

16).

Physicians participating in this study were required to be U.S. or U.K. board-eligible or board-certified psychiatrists who treated at least five patients with schizophrenia each month. Psychiatrists were members of Kantar Health’s online physician panel. Kantar Health administered the 20-minute online survey in January 2012. The Office of Research Protection and Ethics at RTI International granted a consent exemption for this study, and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Survey instrument

To determine attributes to include in the survey, we used an approach based on multicriteria decision analysis and the benefit-risk framework from the Benefit-Risk Action Team (

19,

20). A list of 35 potential benefits and risks was created and was used in written and telephone interviews with seven key opinion leaders in schizophrenia, which resulted in a ranked list of outcomes that were most critical for treatment evaluations. Working with key opinion leaders, reviews of product inserts, and published literature, seven attributes describing antipsychotic treatments for schizophrenia were identified as the most critical. The seven attributes included improvements in symptomatic response in three domains (positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and social functioning) and incidence of four adverse events (weight gain, EPS, hyperprolactinemia, and hyperglycemia).

The levels describing each attribute were designed to encompass the range of symptoms observed in clinical practice and the range over which respondents are willing to accept trade-offs among attributes (

Table 1). To accommodate the different backgrounds of respondents, the levels of positive and negative symptom attributes were defined with three types of language: a level label (for example, “very much improved”), a change in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) subscore, and an example. Although the positive and negative subscores of the PANSS provide well-defined degrees of symptoms, respondents without expertise in clinical trials may not know the PANSS scoring system well. The degree of change in PANSS subscore for each level label was based on a linking analysis between PANSS scores and the scores for Clinical Global Impression–Improvements (

21).

Before fielding the final survey instrument, a draft instrument was tested in open-ended interviews with 25 U.S. psychiatrists. Interviews were conducted to test the instrument’s clarity, confirm that attributes and levels were appropriate, and assess respondents’ willingness to accept trade-offs among the seven treatment attributes. After these pretests, minor changes were made to the wording.

Each respondent answered eight choice questions on the basis of a statistically efficient experimental design (

22–

24). The choices consisted of a pair of treatments, each characterized by profiles of various attributes and their levels; physicians were asked to choose which treatment was better for a hypothetical patient with schizophrenia. [An example of a choice question is available in an online

data supplement to this article.] In addition, to assess the impact of formulation and adherence, respondents answered a second set of four choice questions. These questions pertained to treatment attributes, such as formulation (daily pill, monthly injection, or injection every three months), percentages of patients with at least 25% improvement in positive symptoms (25% or 50%), and percentages of patients experiencing EPS (5% or 15%). The hypothetical patient in these questions was initially described as fully adherent. After responding to each of these questions, respondents were then informed that the hypothetical patient had missed or skipped either 20% or 50% of his oral antipsychotic medications in the past. Physicians were asked to reevaluate the same treatment, given the new information. [An example of the second set of questions is available in the online

supplement.]

Statistical analysis

Responses to the first set of choice questions were analyzed by using a random-parameters logit (RPL) model, where the dependent variable was the medication profile chosen, which was regressed against the attribute levels. The model estimated relative decision weights for the attribute levels shown in

Table 1 that best fit the observed pattern of choices. The resulting parameter estimates thus quantified the relative importance of each attribute level (

3,

25,

26). For the second set of choice questions, we used a bivariate-probit model to jointly estimate relative importance weights for the formulation, the chance of improvement in positive symptoms, and the change in EPS, given the patient’s adherence history. All analyses were conducted with NLOGIT 4.0.

In both the RPL and the bivariate-probit models, the model coefficients indicated the change in the relative importance weight that would result from a change in attribute levels. The difference between the importance weights for the best and worst levels for each attribute can be interpreted as the overall mean relative importance between the worst and best levels of that attribute, over the specific ranges included in the hypothetical treatment profiles (

11,

26,

27). Larger mean scores indicate a greater perceived benefit. Therefore, overall mean relative importance is interpreted as the increase in perceived treatment benefit that would result from switching from a medication with the worst level of that attribute to a medication with the best level of that attribute. To facilitate interpretation of the results from both models, we assigned the highest mean relative importance score from each model a value of 10 and scaled the mean relative importance for each of the other attributes relative to the most important attribute. In addition, for each attribute level, we estimated the percentage change in the predicted choice probabilities of physicians selecting a treatment with that attribute level compared with a reference condition (severe positive symptoms, severe negative symptoms, severe social problems, and no adverse events) representing the hypothetical patient not receiving treatment.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 1,700 U.S. psychiatrists and e-mail invitations to participate in the survey by Kantar Health. Predefined quotas of 200 psychiatrists per country were collected for the survey, each of whom had to be board eligible or board certified and currently treating at least five schizophrenia patients each month. U.K. respondents received 48€, and U.S. respondents received the equivalent of 43€.

Six respondents, three from each country, always chose outcome A or outcome B for all eight of the first set of choice questions, indicating that they did not pay attention to the choice questions (

2). Because of concerns about the validity of these responses, the data were excluded from the final analysis, leaving a final sample of 394 respondents.

Of the 394 respondents, 84% (N=331) had been practicing medicine for ten years or more. Approximately 76% (N=299) were male. Most treated more than 20 patients with schizophrenia each month (68%, N=268) and spent more than 20 hours per week providing direct patient care (94%, N=370). On average, respondents prescribed antipsychotic medications to 90% of their patients with schizophrenia, and 79% of these prescriptions were for oral medications. The respondents believed that, on average, patients treated with oral antipsychotics followed the prescribed dosage 68% of the time.

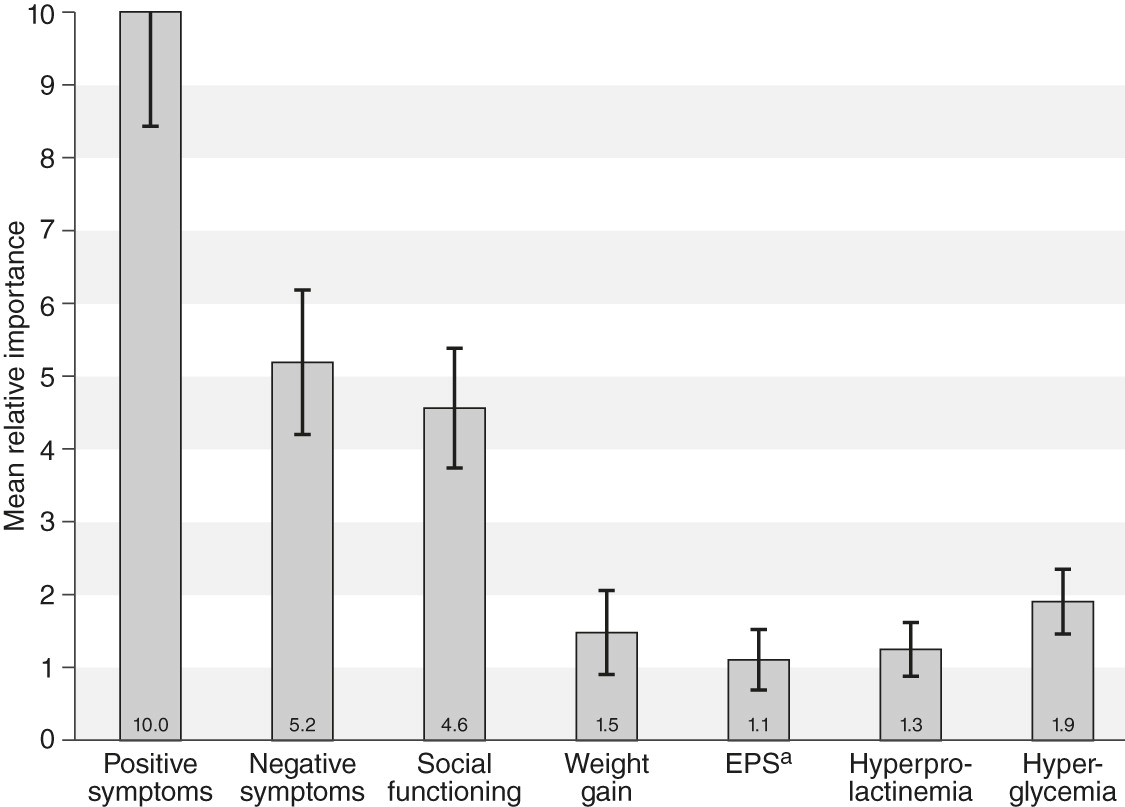

Mean relative importance weights for outcomes

Statistical analysis of the first set of eight choice questions indicated that respondents considered improvement in positive symptoms to be the most important among the outcomes presented. That is, a treatment that would move a patient from “no improvement in positive symptoms” to “very much improved in positive symptoms” would yield more perceived benefit than any other treatment difference included in the survey. This change was assigned an importance value of 10. The outcome next in importance was improvement in negative symptoms from “no improvement” to “very much improved,” which had a mean overall relative importance of 5.2 (95% confidence interval [CI]=4.2–6.2), indicating that improvement in negative symptoms was approximately half as important as improvement in positive symptoms (p<.05).

The relative importance of the other attributes, in decreasing order, were improvement in social functioning from severe to mild problems (the scale for social functioning extended from mild to severe and did not include a level for no difficulties, because pretesting of the survey indicated that respondents could not accept that a patient with any degree of positive or negative symptoms could have no difficulties in social functioning) (relative importance score=4.6, CI=3.8–5.4), no hyperglycemia (1.9, CI=1.5–2.4), <15% weight gain (1.5, CI=.9–2.0), no hyperprolactinemia (1.3, CI=.8–1.6), and no EPS (1.1, CI=.7–1.5) (

Figure 1).

The model results yielded additional insights about changes in importance for various levels of improvement. For example, for weight gain, the change from a 7% to a 15% weight gain was about three times more important than the change from 0% to 7%. For positive symptoms, the change from “no improvement” to “minimally improved” was more important than the change from “minimally improved” to “much improved,” which in turn was more important than the change from “much improved” to “very much improved.” [Details are available in the online

supplement.]

Initially, results were estimated separately for U.S. and U.K. respondents. However, because no difference was found between the judgments of respondents from the two countries, we present pooled results.

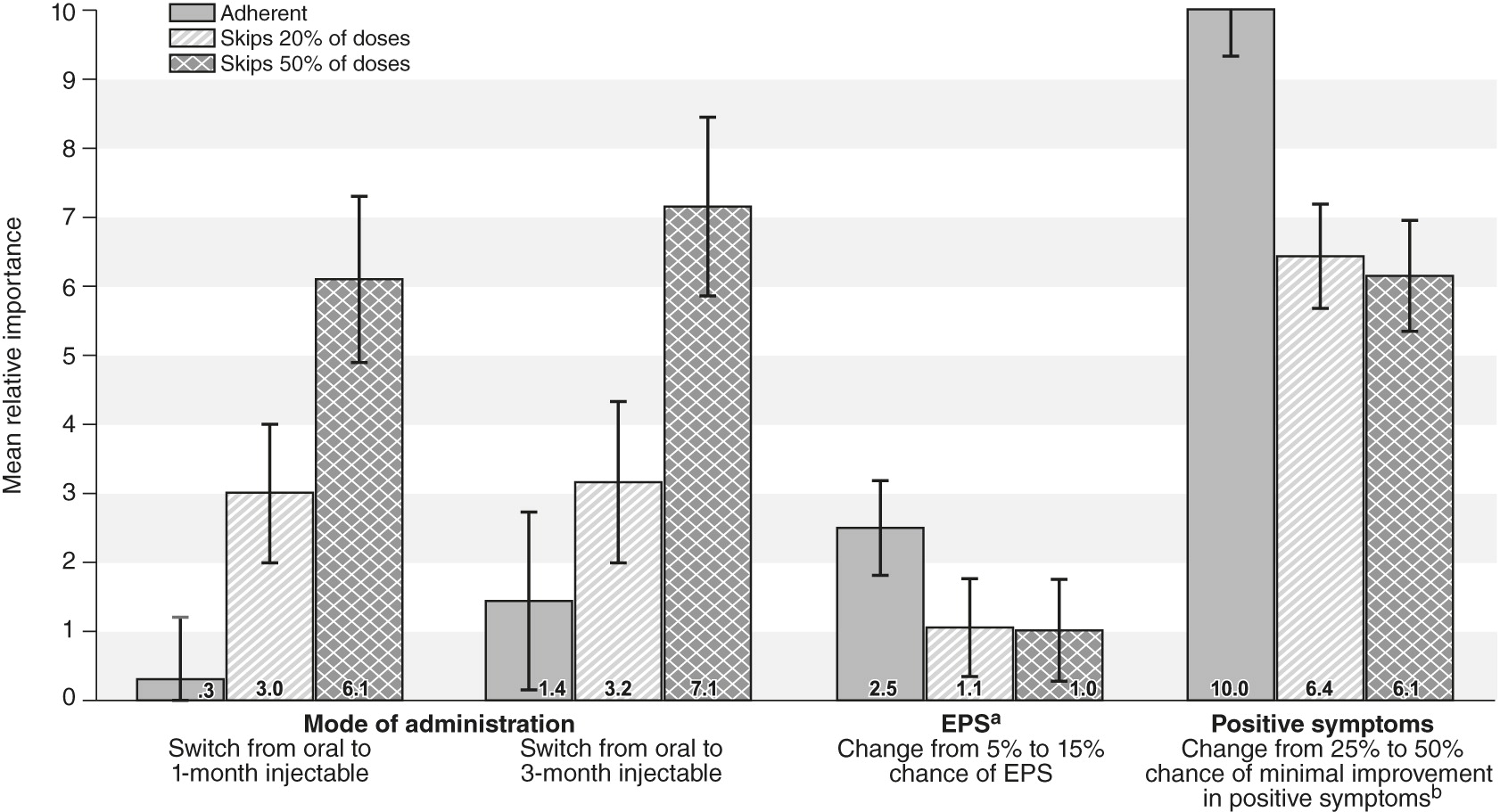

Mean weights for formulation and adherence

In regard to adherence, the percentage of patients with at least a 25% improvement in positive symptoms was the most important attribute, with a mean relative importance score of 10. The attribute next in importance was the percentage of patients with EPS (relative importance score=2.5, CI=1.8–3.2), followed by changing the administration mode from a daily pill to an injection every three months (1.4, CI=.2–2.7). As the hypothetical patient’s adherence decreased, the mode became more important, and injections were increasingly preferred over daily pills (p<.05). For patients who missed or skipped 50% of their doses of oral medication in the past, respondents regarded a 25% improvement in positive symptoms as equal in importance to switching a patient from an oral medication to a monthly injectable.

Figure 2 shows the mean relative importance scores and 95% CIs for the three levels of patient adherence.

Discussion

This study built on prior work in the area of assessing physicians’ judgments in regard to benefits and harms in three key ways. First, using a structured benefit-risk framework approach with input from key opinion leaders and literature review findings, we identified a set of the critical benefits and risks that physicians consider when making treatment decisions about second-generation antipsychotics. Second, by incorporating formulation into a set of choice questions, we obtained quantitative data about trade-offs (degrees of benefits and degrees of risks) in formulation preference. Third, by providing information on the hypothetical patient’s past adherence to oral antipsychotics, we assessed how formulation preferences depended on physicians’ perception of adherence. These aspects allowed for more refined benefit-risk assessments among second-generation antipsychotics.

A key finding was that physicians regarded minimal improvement in severe positive symptoms as having greater or equal importance compared with any of the four adverse events. Changes in positive symptoms from “severe” to “much improved” were more important than any change in other symptoms or adverse events assessed in the survey. This finding suggested that the main driver in decisions about second-generation antipsychotics was at least some lessening of positive symptoms. Once a patient with severe positive symptoms showed minimal improvement, the difference between gaining further improvement in efficacy and causing adverse events grew larger. A similar argument applied to social functioning, although to a lesser degree. We did not examine the rationale behind the measurements of relative importance. However, a psychiatrist’s first concern might be to stabilize a psychotic patient, considering adverse events as both secondary and much more controllable by fine-tuning the dose and choice of antipsychotic.

A second key finding was the general similarity of the weights given to avoiding adverse events. Although hyperglycemia and weight gain had higher point estimates than the other adverse events, the differences were not statistically significant (

Figure 2).

A third key finding was the importance of switching a patient from an oral second-generation antipsychotic to an LAI. For adherent patients, no difference was found between these choices. For a patient with a history of missing 20% of doses, respondents showed a statistically significant preference for both the one- and the three-month LAIs over the oral form. This preference was equal to an approximate 8% change in probability of minimal improvement in positive symptoms. In other words, given the choice between a highly effective oral drug and a somewhat less effective LAI, respondents would choose the LAI. For patients with a history of missing 50% of their doses, the trade-off was even more noteworthy: respondents considered a 25% reduction in a drug’s chance of providing minimal improvement in positive symptoms as less important than switching the patient to an LAI. These results may be of value in both regulatory approval and physician and patient decisions regarding second-generation antipsychotics.

The findings were similar to those of other published studies in which respondents rated reductions in positive symptoms and improvements in social functioning as more important than reductions in negative symptoms and EPS (

5). A recent study that compared patient and psychiatrist treatment decisions found that both made treatment decisions primarily on the basis of improvement in positive symptoms but that adverse events were more important to patients than to psychiatrists (

28). Other studies have shown that medication side effects are of greater concern to patients and their families than to clinicians (

6–

10). A particular benefit of DCE studies is that this approach provides numeric data on trade-offs between attributes that are of great value for quantitative benefit-risk analyses.

As with most DCEs, our survey was pretested but not formally validated. We designed the survey so that respondents would interpret the attributes consistently and in the manner intended. However, except for results showing face validity, it is not possible to prove consistent interpretation by respondents. The choice tasks can also be cognitively difficult for untrained respondents, although the training section of the survey included both attribute definitions and practice questions to enable respondents to gain relevant experience before the results were captured. Also common to most DCEs is that all patient scenarios and treatment choices were hypothetical. Unfortunately, DCE tasks limit the number of endpoints that can be considered simultaneously by survey respondents. The structured approach we employed for benefit-risk endpoint selection was a means to mitigate this limitation. The levels for social functioning did not include a “no difficulties” or complete cure level, unlike the levels for positive and negative symptoms. If the full range of social functioning had been included, social functioning might have shown greater importance than negative symptoms. Because of budget and time constraints, this study used a quota sampling approach and surveyed a convenience sample of English-speaking psychiatrists from an online panel, making it difficult to generalize the results of the study to all U.S. and U.K. psychiatrists. Finally, these surveys ideally should be conducted via in-person interviews. However, results from previous online DCEs were, in general, not statistically different from those elicited through face-to-face interviews (

29,

30), and results from several DCEs that used online physician panels have been published (

2,

4,

15).

Conclusions

Balancing the benefits and risks of treatments is the core of treatment decisions made by health authorities, physicians, and patients. Understanding the importance that physicians and patients place on the various benefits and risks of second-generation antipsychotics and how formulation affects those trade-offs provides insight into past decisions and useful information for future decisions.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for the study was obtained from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The authors thank Vikram Kilambi, B.S., B.A., Angelyn Fairchild, B.A., and Gail Zona, B.A., for their assistance at various stages of this project. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Dr. Markowitz is an employee of UCB Biosciences, was formerly employed by Janssen Scientific Affairs, a Johnson & Johnson company, and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. Dr. Levitan is an employee of Janssen Research and Development, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson company, and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson, Baxter International, Inc., Pharmaceutical HOLDRS Trust, and Zimmer Holdings, Inc. Ms. Mohamed is an employee of Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and owns stock in Bayer. Dr. Alphs is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, a Johnson & Johnson company, and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Citrome has engaged in collaborative research with or received consulting or speaking fees from Alexza Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Envivo, Forest Laboratories, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Inc., Lundbeck, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Reckitt Benckiser, Reviva Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Shire, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International. The other authors report no competing interests.