The first psychotic episode represents a challenging period for patients and families. Patients frequently feel overwhelmed with hopelessness, fear, guilt, and shame (

1,

2). They must cope not only with their new clinical condition but also with the stigma they encounter in everyday life as a result of their psychiatric diagnosis (

3). Stigma can be seen as an overarching concept that includes problems of knowledge (ignorance or misinformation), attitudes (prejudice), and behavior (discrimination) (

4). Discrimination against persons with mental health problems has important ethical, political, and clinical implications (

5–

7).

Research on discrimination in regard to mental disorders has mainly focused on attitudes and emotions in the general population and professionals toward patients (

8–

14). Only recently has research begun to explore patients' self-reported experiences of discrimination; all of the more recent studies have examined patients with long-standing psychiatric conditions (

2,

7,

15–

20). To the best of our knowledge, no study has specifically addressed the ways in which discrimination (that is, the behavioral component of stigma) affects the lives of persons experiencing a first episode of psychosis. This research gap represents a major drawback, because this is a specific population with well-defined characteristics. In fact, the literature reports a substantial difference between the clinical and social needs of this group and those of patients with illnesses of longer duration. The former are generally young, living with their families, attending educational or training systems, and seeking to enter the labor market (

21,

22). Patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis may therefore report more discrimination in life domains pertaining to young people’s social world (such as training or education, friendship, and family relations), but empirical data are lacking.

Moreover, the first psychotic episode is a complex period characterized by the occurrence of extremely severe symptoms, which are frequently associated with an insidious functional decline that dramatically disrupts the patient’s quality of life and community integration (

23). Associations between symptoms, social functioning, and discrimination merit greater empirical focus, because research has shown that greater perceived social discrimination among those with longer-term mental disorders is significantly associated with more severe symptoms (

16) and more functional impairment (

24,

25). This association, however, has not yet been tested among patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis.

In an effort to bridge these knowledge gaps, this study examined a sample of patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis with the specific aim of investigating experienced and anticipated discrimination patterns and their associations with sociodemographic and clinical variables. Experienced discrimination refers to an individual's perception that he or she has been treated unfairly by others because of a mental health condition. Anticipated discrimination occurs when a person limits involvement in important aspects of everyday life because of the fear of being discriminated against.

We addressed the following hypotheses. First, given that the needs of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis differ substantially from those with longer-standing illness, first-episode patients were expected to report more discrimination in life domains specifically pertaining to young people’s social world (for example, training or education, friendship, and family relations). Second, given that time from first contact with mental health services was found to be associated with higher levels of experienced discrimination, first-episode patients were expected to report, on average, lower levels of experienced discrimination than patients with chronic psychosis. Third, higher levels of perceived discrimination were expected to be associated with more severe symptoms and poorer social functioning, as assessed by both clinician-rated and patient-rated measures. To address the first two hypotheses, data from people with long-standing psychosis recruited in Italy for the INDIGO (INternational study of DIscrimination and stiGma Outcomes) schizophrenia study were also used (

7,

19).

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted within the framework of the Psychosis Incident Cohort Outcome Study (PICOS), a multisite collaborative study that examined the relative roles of clinical, social, genetic, and morpho-functional factors in predicting outcomes among patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis who were in contact with public mental health services in the Veneto Region, northeast Italy (

22,

26). This study assessed experiences of discrimination in a sample of first-episode patients recruited from a subset of sites (30%) participating in PICOS; sites were selected on the basis of availability of local resources to perform these evaluations.

Geographical and care context

The Veneto Region has a population of 4.6 million. Most residents are Caucasian, and 10% are immigrants. The urban structure is polycentric, with a few large-scale cities (>200,000 inhabitants) and many mid- and smaller-scale cities.

Psychiatric care is delivered by the Italian National Health Service through its Departments of Mental Health (DMHs), which are responsible for the provision of comprehensive and integrated care to the adult population living in a geographically defined catchment area of approximately 250,000–300,000 inhabitants. Multidisciplinary teams operating the DMHs provide a wide range of programs, including inpatient care, day care, rehabilitation, outpatient care, home visits, 24-hour emergency services, and residential treatment for long-term patients.

Participants

The target group for PICOS was individuals aged 15–54 years who were residents in the Veneto Region and had first contact with any mental health service from January 2005 to December 2007, with evidence of the following: delusions, hallucinations, thought disorder, or negative symptoms of psychosis, irrespective of cause (

26). The primary exclusion criterion was any previous presentation or treatment for psychotic illness, other than initiation of treatment for the current episode during the previous three months. Written informed consent was obtained from participants. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the coordinating center (Azienda Ospedaliera di Verona) and the local sites.

Measures

Discrimination was assessed by researchers who were not involved in the care process, using the Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC-10) (

7), which has good psychometric properties (

27). In a face-to-face interview, DISC-10 respondents are asked to comment on various key areas of everyday life and social participation. The first section collects sociodemographic information. The second section evaluates experienced discrimination (for example, “Have you been treated differently from other people in making or keeping friends because of your mental illness diagnosis?”). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0, no difference; 1, slight disadvantage; 2, moderate disadvantage; and 3, strong disadvantage). The third section explores anticipated discrimination—that is, the extent to which respondents limit their own involvement in important aspects of everyday life (for example, “How much have you stopped yourself from applying for work or for training/education because of your mental illness diagnosis?”). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0, not at all; 1, a little; 2, moderately; and 3, a lot); respondents who agree with anticipated discrimination items indicate that they not only anticipate discrimination but avoid activities and give up life goals as a consequence. Two subscores (experienced discrimination and anticipated discrimination) were generated by counting the number of items in which participants reported a disadvantage (that is, scores of 1–3).

Symptoms were assessed by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (

28). Patients’ symptom attribution and awareness of illness were assessed by the Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI-E) (

29). Clinician-rated social functioning was assessed by the Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS) (

30), and patient-rated social functioning was assessed by the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) (

31), the Manchester Short Assessment scale (MANSA) (

32), and the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale (VSSS) (

33). An interrater reliability session yielded an interrater reliability of .90 for the PANSS (Cohen’s kappa).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed by SPSS, version 17.0. All p values were two-tailed with a significance level of .05. Nonnormality of continuous variables was checked, and nonparametric tests were chosen. Comparisons were performed by chi square and Mann-Whitney tests. Correlations were explored by Spearman’s rho coefficient. A multivariate negative binomial regression model (‘nbreg’ Stata command) was estimated with the experienced discrimination subscore as the dependent variable, and a set of potential explanatory variables was specifically selected to address the third study hypothesis: age, anticipated discrimination, gender, nationality, compulsory treatment, education, employment, marital status, diagnosis, and scores on the PANSS, DAS, CAN, SAI-E, VSSS, and MANSA. The same strategy was applied for the anticipated discrimination subscore. All models were performed by the cluster option, which specifies that the observations are independent across groups but not necessarily independent within groups.

Results

A total of 97 patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis were assessed with the DISC-10.

Table 1 summarizes data on the sample’s characteristics.

Table 2 presents the overall profile of experienced discrimination, with responses reporting any disadvantage combined. The most common areas of experienced discrimination (>20%) were relationships with family members, making or keeping friends, keeping a job, relationships with neighbors, finding a job, and dating or intimate relationships.

Table 2 also presents results for anticipated discrimination. A large proportion of patients (approximately 60%) felt the need to conceal their diagnosis. The most frequent areas for anticipated discrimination (>30%) were being avoided by other people and stopping oneself from having close personal relationships and from applying for work, education, or training.

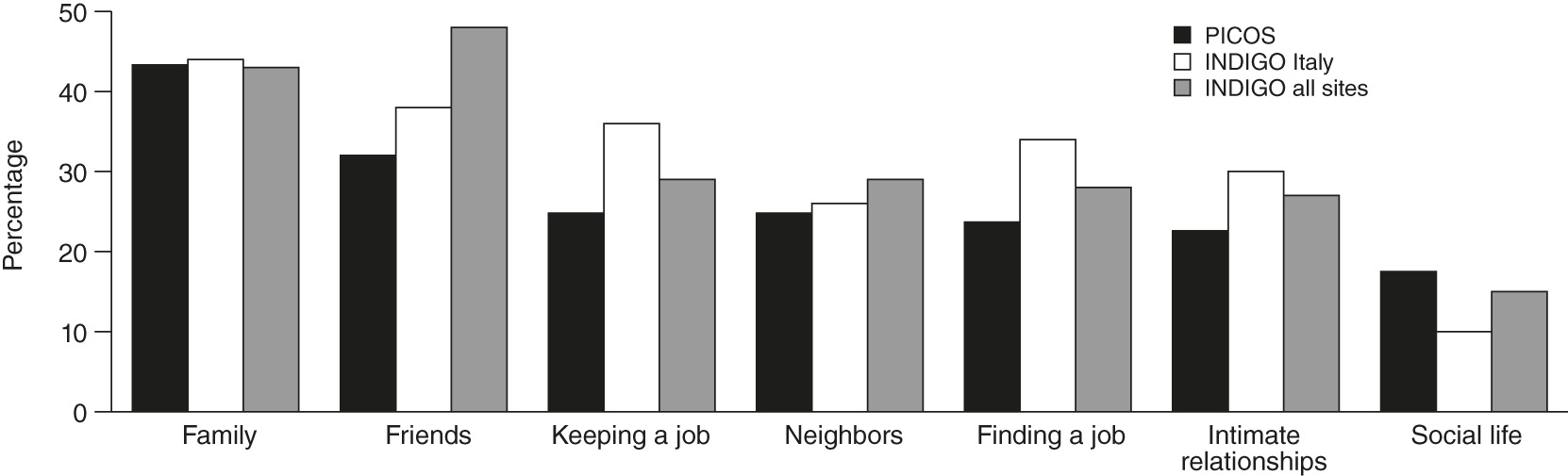

Figure 1 illustrates how experienced discrimination reported by these first-episode patients compares with that reported by patients with long-standing schizophrenia who were recruited in the Italian INDIGO sites (

19) and those who were recruited across all INDIGO sites (

7).

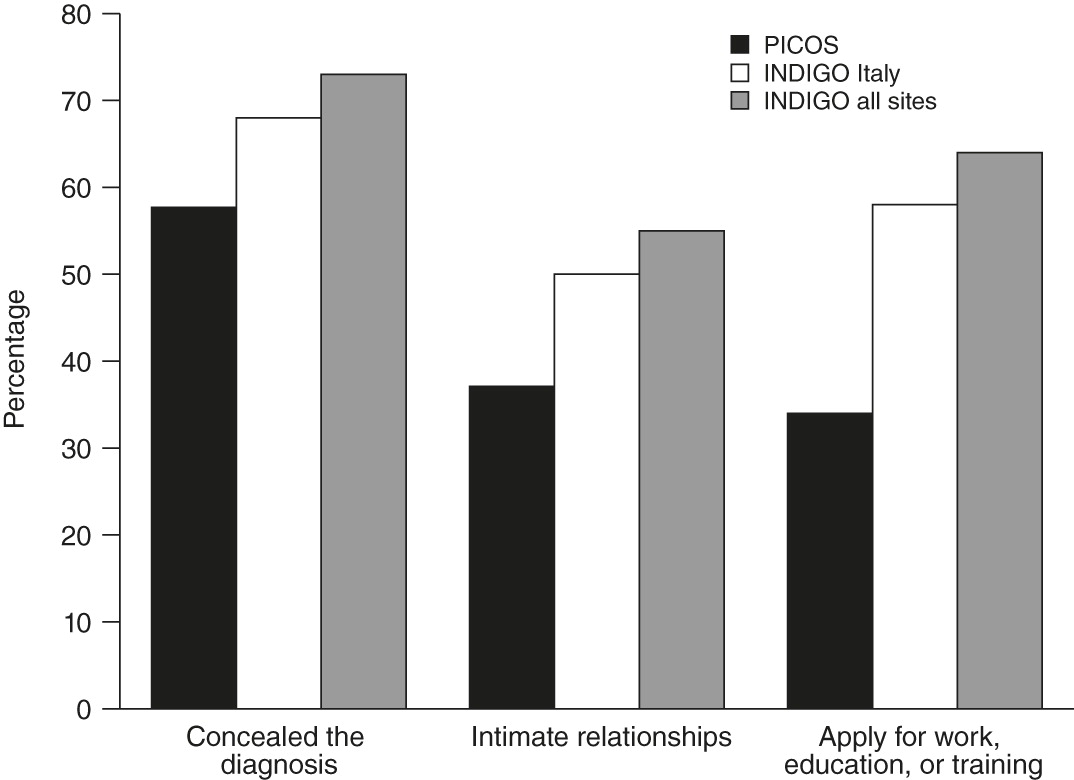

Figure 2 compares anticipated discrimination for these groups.

The multivariate model showed that patients who reported higher levels of experienced discrimination (

Table 3) also reported greater anticipated discrimination, a lower level of education, a higher level of met needs in the functioning domain (that is, self-care, looking after the home, child care, money, and education), and a poorer subjective quality of life in the family domain. It should be noted that met needs represent an index of service provision, because according to the CAN, a need is considered to be met when patients report that there is no problem in a specific domain because of the help provided (but that a problem would exist if no help were provided). Patients reporting higher levels of anticipated discrimination (

Table 3) had higher levels of experienced discrimination and greater illness insight.

Discussion

This study is the first to explore reported experiences of discrimination among persons experiencing a first episode of psychosis. The use of interviews to gather direct self-reports from these individuals in regard to both anticipated and experienced discrimination (compared with the use of hypothetical scenarios or vignettes) represents a methodological strength of this study. In fact, most research on discrimination against persons with mental health conditions has been largely descriptive and based on surveys of public attitudes toward hypothetical (versus real) situations. The research has therefore mostly explored what “normal” people might say about psychotic patients, rather than the ways in which discrimination is experienced by people who have a mental illness. Indeed, we propose that gathering patient reports on their own experiences of discrimination may serve the further purpose of empowering them by giving them a voice and acknowledging the validity of their experiences.

Our main finding was that depending on the form of discrimination, approximately one-half to one-third of first-episode patients reported having experienced discrimination in their everyday lives. Experienced discrimination mainly affects life domains that pertain to an individual’s basic requirements for achieving full social integration, such as family, friendship, employment, and intimate relationships. Moreover, anticipated discrimination was also common. Up to 37% of individuals in the sample were affected by some form of anticipated discrimination, further limiting these patients’ access to a number of important life opportunities (such as making or keeping friends and seeking close relationships) and community resources. Anticipated discrimination could lead patients quite early in their illness trajectory to give up on the idea of being able to benefit from opportunities and from participating in everyday life activities, which would negatively affect social outcomes and individually defined life goals (the so-called why try effect) (

34).

Furthermore, we found that most of the surveyed patients actively concealed their condition from others. Such concealment is a major treatment issue, because nondisclosure of a mental health condition can interfere with help-seeking behavior, creating a major obstacle to receiving effective treatment. Some patients may avoid treatment out of fear of being judged or discriminated against. Others may avoid dealing with issues related to their mental health condition because doing so could have a negative impact on their self-esteem, which may already be compromised. Concealment also has general negative effects, such as reduced self-esteem, increased psychological distress, impaired interpersonal relations, and reduced relatedness to key institutions such as work (

35), whereas disclosure or coming out about one’s mental illness may have positive effects (

36).

Regarding our first hypothesis, we expected that compared with patients with chronic schizophrenia, first-episode patients would report higher discrimination in life domains specifically pertaining to young people’s social world (such as training or education, friendship, and family relationships). This pattern was expected, given that the needs of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis—who are generally young, living with their families, attending educational or training systems, and seeking to enter the labor market—substantially differ from those of individuals with an illness of longer duration (

21,

22). This hypothesis was not confirmed because we found that the main sources of discrimination reported by first-episode patients (family, friendship, and job) substantially overlap with those observed among people with chronic schizophrenia (

7,

19) (

Figure 1). This finding suggests that interpersonal relations (either with family members or with people outside the family) and employment are frequently problematic domains for patients with psychosis in general, regardless of their illness phase. Patients must deal with these difficulties at a very early stage of their illness, and these problems tend to remain unsolved.

The picture differs for anticipated discrimination, because a phase-specific pattern was observed. Whereas most first-episode patients reported problems in keeping or making friends and establishing intimate relationships, job domain was the most problematic area for patients with chronic schizophrenia (

7,

19) (

Figure 2). The key role of relationships for young people versus the work-related and financial problems that commonly affect middle-aged individuals might account for this difference. In addition, the degree of demoralization implied in the DISC-10’s construct of anticipated discrimination may not yet be as high among first-episode patients.

Second, we hypothesized that first-episode patients would report, on average, lower levels of experienced discrimination compared with patients with chronic schizophrenia, because research has found that experienced discrimination is associated with time from first mental health service contact (

7). However, the percentages reporting discrimination were substantially similar among first-episode patients and those with chronic illness; slightly larger proportions of the latter group reported discrimination in areas such as finding and keeping a job, whereas the proportions of first-episode patients reporting discrimination in the social life domain were considerably higher than among those with chronic illness (

Figure 1).

Finally, we hypothesized that higher levels of discrimination would be associated with more severe psychotic symptoms and poorer social functioning (

16,

24,

25). This hypothesis was partially confirmed. We found that discrimination was not associated with levels of psychopathology and that higher levels of discrimination were associated with poorer self-perceived social functioning. In fact, patients who reported higher levels of discrimination reported higher levels of need in the functioning domain (self-care, looking after the home, child care, money, and education) and poorer life satisfaction with family relationships. This finding provides further support for the idea that anticipated discrimination acts as a barrier for people with mental disorders in achieving full integration into their social networks. It also suggests that the process leading to social exclusion can occur in various illness phases—in the beginning and in the longer term.

It should also be noted that patients with a higher level of insight into their illness reported greater levels of anticipated discrimination. Thus illness insight appears to play a role in mediating patients’ clinical condition and appraisals of their social environment (

37,

38). A number of studies have reported that awareness of having a mental disorder is a “double-edged sword” for patients with psychosis. Poor insight is linked to poorer treatment adherence, poorer clinical outcome, poorer social functioning, greater vocational dysfunction, and difficulties in developing working relationships with mental health professionals (

39). On the other hand, greater insight has been associated with higher levels of dysphoria, lower self-esteem, and diminished well-being and quality of life (

40–

42). Thus patients’ greater awareness of the negative consequences of their psychosis-related symptoms and disabilities can lead them to more easily recognize the discrimination that exists in society toward individuals with mental health problems and, possibly, toward themselves.

Acceptance of having a severe mental disorder, however, depends on the meanings a person attaches to his or her diagnosis (

24). Greater awareness of illness could lead to hopelessness and self-devaluation; understanding that one has a psychotic disorder may lead to a belief that one is not capable of achieving valued social roles. Therefore, mental health professionals should pursue all efforts to empower patients to take an active role in their everyday life and in treatment decisions. Some promising interventions, such as narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy (

43), specifically target self-stigma. Insight into mental illness with a personal and nonstigmatized interpretation may allow people with severe mental health problems to use insight as a beneficial factor in their recovery process (

44).

This study also had several limitations. First, given its cross-sectional design, no conclusions can be drawn regarding causality, and alternative explanations for the findings cannot be ruled out. Second, no information was available on labeling experiences of participants (that is, when and in what contexts participants were labeled as “mentally ill” or “psychotic”). Third, the relatively small sample limits the generalizability of the findings. Fourth, no control or comparison group was used, which prevents our sample of first-episode patients from being compared directly with other groups. Fifth, because the sample surveyed was a convenience sample, selection bias might also have occurred, further limiting the generalizability of findings. Sixth, generalizability may also be limited by the fact that participants were recruited from the mental health system, and they may have been more likely to have had positive attitudes toward help seeking, more illness insight, and more labeling experiences as a result of their mental health service use.