Use of second-generation antipsychotics substantially contributes to rising expenditures for Medicaid-enrolled children (

1–

4). Although primarily indicated for treatment of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, most second-generation antipsychotic use among children is for off-label treatment of other mood and behavioral disorders (

1,

5). Second-generation antipsychotic use is controversial because efficacy has not been established for these off-label treatments and because there are side effects, including metabolic disorders (

6) and elevated risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (

7–

9).

In recent years, second-generation antipsychotic use has grown considerably across the United States, but rates of increase and levels of use vary widely across states and regions (

10,

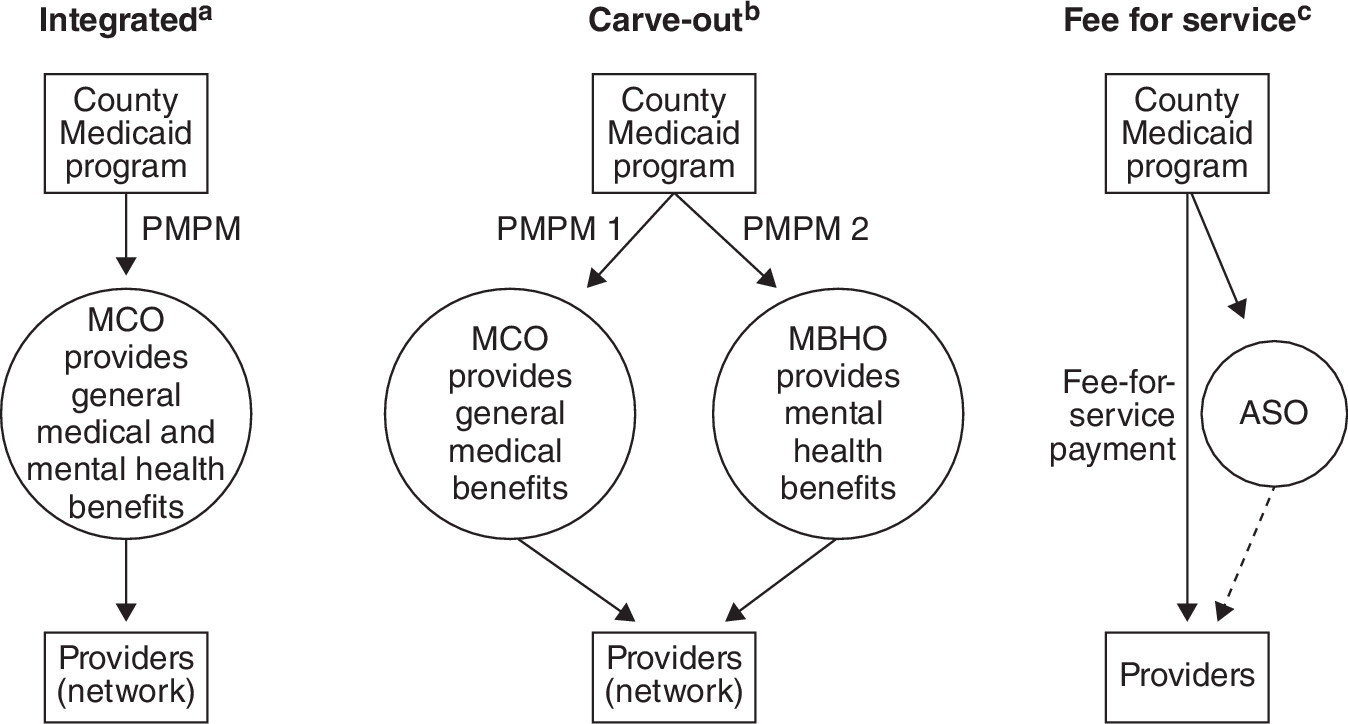

11). One possible influence on diverging utilization rates may be differences in the organization and delivery of Medicaid mental health services across localities. Some programs reimburse providers on a fee-for-service basis (that is, based on a defined fee schedule). Others use managed care—either integrated plans, in which a single plan receives a capitated payment to cover both general medical and mental health benefits, or carve-outs, in which mental health benefits are paid for with separate capitated payments that cover services delivered by managed behavioral health organizations or local mental health authorities (

12).

Figure 1 illustrates these three structures.

Our objective with this study was to examine differences in second-generation antipsychotic use across Medicaid organizational structures. We hypothesized that second-generation antipsychotic use would be lower under a capitation structure than a fee-for-service structure because theoretical and empirical research has found that capitated plans generally reduce the use of high-cost psychotropic medications (

13,

14). This reduction can operate either indirectly through selective contracting by Medicaid programs with cost-conscious managed care organizations (

15) or more directly through financial incentives for individual providers (

13).

It is unclear, however, which type of capitated arrangement—integrated or carved out—might have a larger impact on second-generation antipsychotic use. On the one hand, integrated programs may lower second-generation antipsychotic use through greater coordination between primary care and specialty mental health providers, which could foster greater use of alternative therapies or reduce the use of hospitalizations where antipsychotic use is often initiated (

16,

17). On the other hand, carve-out systems usually rely on only one specialty managed behavioral health provider, which, compared with other providers, may possess greater case management and utilization review capabilities as well as a less fragmented system in which to target interventions toward medication management (

18). Although more specialty service coordination might increase access to some services (

19), it could also reduce perceived overuse of treatments such as second-generation antipsychotics.

Methods

Classifying behavioral health organizational structures

We conducted a comprehensive review of Medicaid policies in 82 counties in 34 states covering the period 2004–2008. Counties were the unit of analysis because managed care arrangements are often established at the county level and because there is county-level heterogeneity within large states such as Texas. The predominantly urban counties in this study represented different Medicaid systems and provider environments (

Table 1). Study counties were part of a prior national study of Medicaid-enrolled children (

20). We began with 97 counties but excluded 12 because they were not contained in our child-level Medicaid data; we excluded three additional counties because of poor data quality for psychotropic prescriptions (defined as rates below 1% of all children within a county). Inclusion of these three counties did not alter our main findings, however.

To measure Medicaid organizational structures, we reviewed policy documents from state Medicaid programs, managed care providers, and county agencies. We supplemented our review with government and research reports. Coding was conducted independently by two team members using common criteria. Initial intercoder agreement was attained in 66 cases (80%). Ambiguous cases were resolved with consultation with key informants (academic researchers and clinicians) in states where study counties resided. Study approval was granted by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Of note, some counties with capitated structures allowed high-need populations to remain in fee-for-service arrangements during the study period. We defined the predominant organizational structures at the county level rather than the child level, both because we did not have a comprehensive measure of which counties allow specific groups of children to remain in fee-for-service plans in otherwise capitated counties and because such children are likely not comparable with those in the general population in counties with predominantly fee-for-service plans.

We also examined whether pharmacy benefits were capitated versus reimbursed as fee for service (defined independently of the behavioral health plan structure). Capitated arrangements include drugs in a per-member-per-month payment to a managed care organization or mean that pharmacy is handled by a third-party pharmacy benefits manager.

Medicaid Analytic Extract

We linked our county-level measures to cross-sectional, child-level data from the Medicaid Analytic Extract (MAX) national claims database, covering the 2004, 2006, and 2008 fiscal years, during which use of second-generation antipsychotic use escalated among Medicaid-enrolled youths (

10). Demographic, eligibility, and pharmacy data were extracted from the personal summary and pharmacy files.

Our sample was restricted to children ages three to 18 years with at least ten of 12 months of enrollment in the year. Among these children, we focused on those with any stimulant utilization in the year (N=419,226), a large population of children for whom the adjunctive use of antipsychotics is controversial (

21). These youths constituted 3.8% of the total sample with ten months enrollment. Many of these children were being treated for disruptive behaviors related to a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (

22). Because diagnostic classifications in claims data are likely to be unreliable, the identification of stimulant-using children allowed us to best approximate an at-risk population, and furthermore, select for a group in whom the possibility of missing prescription data across counties was less likely; children with recorded stimulant use would be more likely to have complete utilization histories for other psychotropic drugs, given that we had identified their stimulant use.

Child-level covariates

We classified children into eligibility groups by using the following hierarchy: if children had any enrollment in foster care, they were categorized as foster care; if they had any Supplemental Security Income (SSI) enrollment, they were categorized in the SSI group; any other children were categorized in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)/other group. Foster care and SSI accounted for many of the highest service-using children in the Medicaid program, and TANF was the largest and most heterogeneous group.

Age was categorized within calendar years as three to five years, six to 11 years, and 12 to 18 years. Race-ethnicity was coded as white, black or African American, Latino, or other. Children with race classified as unknown were excluded from the analysis (6.8% of the stimulant-using child population). Five counties had >10% of the child population with race unknown; sensitivity analyses for these counties showed equivalent trajectories of psychotropic use over the study period.

Contextual covariates

Using the Area Resource File, we selected county-level covariates representing contextual factors that could influence use of second-generation antipsychotics and mental health services more broadly, independent of county organizational structure. These included the county supply of providers (pediatrician-to-population and psychiatrist-to-population ratios [

23,

24]), the urbanicity of the county (core urban, smaller urban, and suburban or rural [

25]), and sociodemographic characteristics (the poverty rate and uninsured rate [

20]). We also included the percentage of voters in the county voting for the Democratic candidate in the 2008 Presidential election, a proxy for public attitudes influencing social service regulation and provision (

26,

27).

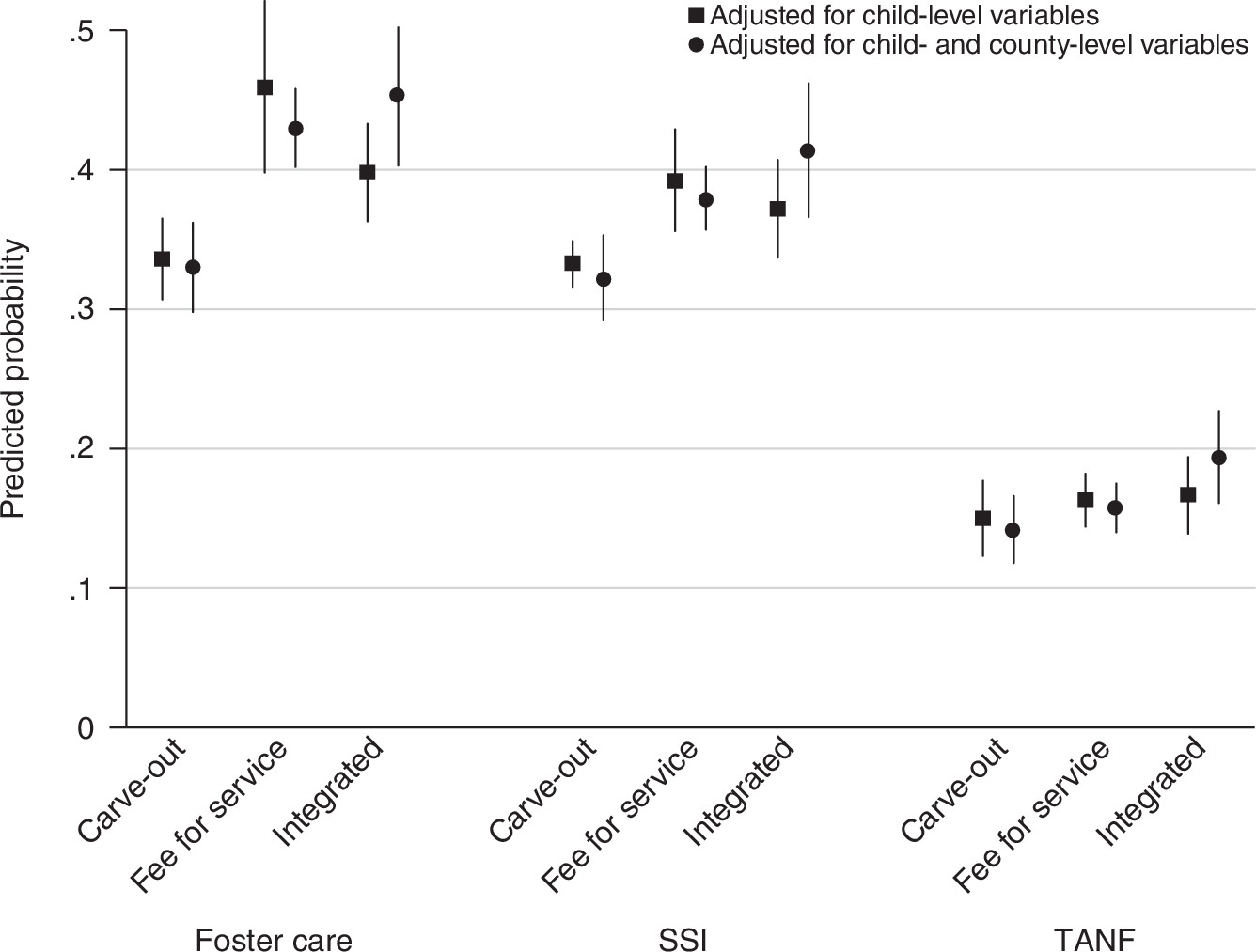

Statistical analysis

We first calculated the unadjusted rates of second-generation antipsychotic use across the organizational structures among sample children by eligibility group. In multivariable analysis, we used logistic regression models, stratified by eligibility group, to compare the odds of second-generation antipsychotic use across county-level organizational structures. Our first set of models adjusted for indicators for pharmacy structure, calendar year, and individual-level covariates. To assess whether these differences were attenuated by other features of county environment, our second set of models further adjusted for county-level contextual characteristics. A robust standard error estimator was used to accommodate clustering of children within counties. Using predicted margins, we calculated regression-adjusted probabilities of second-generation antipsychotic use within each eligibility group and organizational structure, setting the other covariates at the sample means. All analyses were conducted with Stata statistical software, version 12 (

28).

Discussion

We systematically compared use of second-generation antipsychotic medications among Medicaid-enrolled children in 82 counties, focusing on differences across three organizational structures (carve-outs, fee for service, and integrated). We found marked differences in second-generation antipsychotic use across organizational structures. For example, one-third of stimulant-using children in foster care in counties with carve-outs used second-generation antipsychotics, compared with almost half of such children in counties with fee-for-service plans—a 31% relative difference. Second-generation antipsychotic use was relatively higher among children in foster care in counties with integrated versus carve-out structures. Differences across organizational structures were smaller, but still significant, for children in the SSI eligibility group. These patterns persisted after adjustment for other sociodemographic and service system features of counties. Rates of use did not significantly vary across organizational structures for stimulant-using children in the TANF eligibility group, however.

Wider variation in second-generation antipsychotic use across policy structures among children in foster care, relative to other eligibility groups, likely reflects the fact that these children are a particularly vulnerable population with high service use needs. In the absence of other institutional constraints, children in foster care may be targeted more often for second-generation antipsychotic treatment, with less oversight from a consenting guardian or parent (

29). Children in foster care may also experience changes in placement, which can increase disruptions in treatment and reduce oversight (

30).

Our study findings contribute to an emerging literature on regional variation in mental health treatment. Small area differences in the intensity and cost of treatment recently have been identified for psychotropic use among children (

31). Although contextual factors, such as physician supply and poverty that predispose populations to receive more treatment, are undoubtedly contributors (

32,

33), differences across systems persisted after models adjusted for the factors we hypothesized could independently influence use of antipsychotics.

Our study underscores the need to focus on the prescribing behavior of clinicians, which in turn is likely to be influenced by incentives and constraints in different organizational structures. We hypothesized that second-generation antipsychotic use would be lower in both types of capitated systems compared with fee-for-service systems because capitated programs are more likely to contain costs by limiting access to high-intensity services and managing a network of providers. Partially confirming this hypothesis, we found that use of second-generation antipsychotics was consistently higher among children in foster care and SSI populations in fee-for-service versus carve-out systems, but it was not necessarily higher in fee-for-service versus integrated systems.

Higher use of second-generation antipsychotics in counties with fee-for-service versus carve-out structures could stem from a less restrictive prescribing environment. Reducing the barriers to access to mental health treatments is considered to be one positive feature of fee-for-service systems, particularly in light of concerns that Medicaid-enrolled children with mental health problems often receive limited treatment and delayed care (

34). For instance, access to inpatient care is highly managed and may be more limited in carve-out systems (

35). One unintended consequence of a less restrictive environment, however, could be broadened access to treatments such as second-generation antipsychotics, which are prone to overuse and may raise safety concerns. These competing objectives—reducing barriers to treatment and constraining prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics and similar medications—may require more complex reimbursement models and delivery structures. Hence, efforts to constrain use of second-generation antipsychotics should be evaluated within the broader context of efforts to increase contact with providers and increase use of nonmedication treatments (including cognitive-behavioral therapy), which could be particularly beneficial for children with emotional and behavioral problems.

It is less clear why use of second-generation antipsychotics among children in foster care and SSI populations might be higher in counties with integrated structures relative to carve-outs. We posit that some of this difference could be due to more aggressive management of inpatient and outpatient utilization and more coordinated programming of a range of therapeutic behavioral health services by specialized managed behavioral health organizations compared with integrated organizations with less experience and expertise in contracting for mental health services.

Cost management may reduce second-generation antipsychotic prescribing among primary care clinicians but also buffer use of inpatient care and care in other treatment settings where second-generation antipsychotic use is more prevalent. Relatedly, it is possible that a greater focus on provider credentialing and education could limit second-generation antipsychotic use, although it is unknown whether these efforts are greater within carve-out structures. Further investigating these differences in delivery and regulation of treatment is a goal for future research.

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting our findings. First, some service utilization may be underreported in the MAX for managed behavioral health care enrollees (

36). Reassuringly, recent studies have found that patterns of prescription medication utilization in the MAX are consistent between managed care and fee for service (

37). As noted, we also mitigated concerns about underreporting by restricting our sample to children who already had a recorded stimulant prescription fill. Second, we did not adjust for diagnoses or clinical symptoms because of concerns of systematic bias in underreporting across organizational structures. As such, we could not assess patterns of service use within particular diagnostic groups or levels of clinical need.

Third, as mentioned, we focused on the predominant organizational structures in the counties, but we could not systematically track cases where children in foster care or those in the SSI program may have been exempted from managed care. Because such children are sometimes allowed to remain in fee-for-service Medicaid in counties with managed care for other populations, our results for these groups may underestimate differences between fee-for-service and other structures. Finally, we emphasize that although our cross-sectional study design can identify important associations, it cannot establish causality. There may be other unmeasured features of counties that simultaneously influence choice of organizational structure and prevalence of second-generation antipsychotic prescribing. Future research, employing pre-post comparisons, might enable better identification of causal mechanisms. Research might also examine the contribution of organizational structure to regional variation in antipsychotic use relative to other contextual variables.

Conclusions

The differences across organizational structures we identified in our study warrant further research, both to understand potential pathways through which organizational structures shape provider behavior and to identify the long-term impact on safety and quality of care.

Efforts to constrain overuse of second-generation antipsychotics among Medicaid-enrolled children will require some providers to change their prescribing patterns. Although carved out Medicaid mental health benefits could reduce use of second-generation antipsychotics in populations of children, a recent trend toward more integrated services should prompt closer investigation of other tools for tailoring second-generation antipsychotic use across a variety of settings. These tools include formulary restrictions, prior authorization, provider education (that is, academic detailing), and expanded access to alternatives to pharmacotherapy (including psychotherapy).