The U.S. military force includes two components. The full-time, or active duty, component includes more than 1.4 million active duty service members, and the part-time, or reserve, component includes more than 1.2 million reservists. Although reservists are part-time soldiers—training one weekend a month and 15 days annually—when activated for deployment, they experience traumatic combat exposures at levels comparable to those of active duty personnel (

1). Furthermore, reservists encounter a broad range of civilian challenges that are largely not germane to active duty personnel (civilian employment, for example) (

2,

3). There is abundant evidence that both the military (

4) and the social stressors (

2,

3) experienced by reservists are associated with poor psychiatric health. In turn, the consequences of psychiatric disorders are profound. At the individual level, these stressors reduce quality of life and increase physical symptom severity (

5) and aggressive actions (

6,

7); at the population level, the estimated economic burden of psychiatric illness in the United States is $300 billion (

8).

The availability of effective treatments for psychiatric disorders provides an opportunity to minimize the burden of population-level psychiatric illness by ensuring that service members with psychiatric disorders receive care (

9). Unfortunately, most reservists who screen positive for psychiatric disorders report not receiving care (

10). There is evidence in the nonmilitary research literature that treatment-seeking behaviors vary greatly among anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders (

11–

13). The best available evidence suggests that persons with substance use disorders delay treatment the longest after disorder onset, whereas persons with mood disorders more readily perceive a need for professional help and seek both general medical treatment and specialized psychiatric treatment at greater rates than those with anxiety or substance use disorders (

11,

13).

Although there is reliable evidence that psychiatric disorder categories affect treatment seeking among civilians, military personnel are provided robust, equally distributed, psychiatric service access that on face value should reduce sociodemographic treatment disparities often documented in civilian populations (

14). However, no study to date has longitudinally identified treatment-seeking behaviors across various psychiatric disorder categories in a representative sample of military personnel that was not limited to recently deployed service members. Therefore, we aimed to assess whether certain psychiatric disorder categories are associated with likelihood of psychiatric service use; whether individual characteristics affect the likelihood of psychiatric service use; and which individual characteristics, lifetime or current psychiatric disorder, or previous lifetime psychiatric service use has the greatest effect on treatment seeking by military personnel.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and military characteristics of the 528 participants. The sample was predominantly male (88%), non-Hispanic white (89%), and enlisted (89%); had served at least one deployment (61%); and was a mean age of 30. Further, 64% had a lifetime psychiatric disorder, 24% had a current psychiatric diagnosis, and 51% had received psychiatric services.

As shown in

Table 2, period prevalence of recent treatment stratified by psychiatric diagnosis category ranged from 468.2 to 726.6 persons per 1,000 person-years for substance use and mood disorders, respectively. The period prevalence of psychiatric service use for respondents with no disorder, one disorder, and two or more disorders was 209.3 persons, 531.1 persons, and 634.2 persons per 1,000 person-years, respectively (21%, 53%, and 63% of persons per year, respectively).

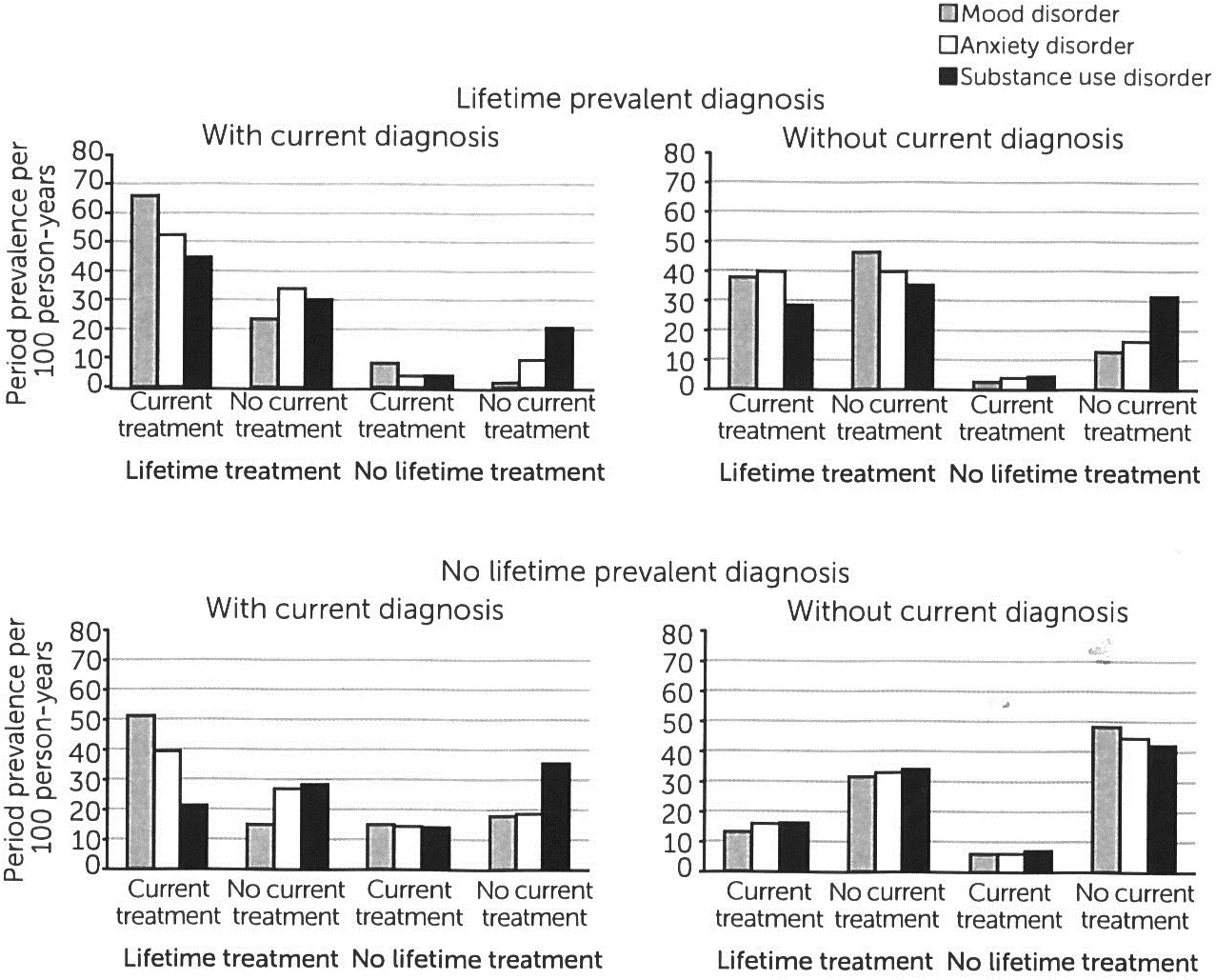

Data on lifetime and current prevalence of psychiatric diagnosis and co-occurring disorders stratified by lifetime and recent treatment are presented in

Figure 1 in the form of period prevalence per 100 person-years. Each of the figure’s four quadrants presents a subfigure of one of four potential lifetime and current psychiatric diagnosis categories; disorder categories are not mutually exclusive (in other words, a respondent with co-occurring disorders is represented in both lifetime prevalent diagnosis quadrants). Mood disorders consistently had the highest period prevalence of recent and lifetime treatment among current diagnoses (specifically, lifetime prevalent diagnosis with current diagnosis, no lifetime prevalent diagnosis with current diagnosis), whereas substance use disorders consistently had the highest period prevalence of reporting neither lifetime nor recent psychiatric treatment.

In bivariate analysis (

Table 3), women (OR=1.9) and separated, divorced, or widowed respondents (OR=1.6) were significantly more likely than comparison groups to have used recent psychiatric services. Respondents with any current disorder were 4.4 times more likely than others to report recent treatment, with mood disorders most highly associated (OR=9.1) and substance use disorders (OR=2.0) least associated with treatment. Respondents with any lifetime psychiatric disorders and those reporting previous lifetime psychiatric service use were 3.2 times and 4.4 times more likely than others, respectively, to report recent treatment.

In the multivariable GEE (

Table 4), current mood disorder was the strongest predictor of recent treatment (AOR=5.0), whereas current substance use disorder was not associated with psychiatric service use. Lifetime pharmacotherapy (AOR=4.1) and psychotherapy (AOR=1.4) significantly predicted recent treatment. No sociodemographic or military characteristics met the a priori model specification criteria described in the methods and were consequently removed from the final model.

Discussion

Using data from a representative sample assessing reservists’ treatment-seeking behaviors, we found, first, an annualized rate of 31% of persons per year accessed psychiatric services between 2010 and 2012. This annualized rate of psychiatric service use is higher than previous reports in representative military (

21,

22) and nonmilitary populations (

23). In studies examining both the general U.S. population and active duty U.S. Army soldiers, approximately 20% of all persons reported past-year use of psychiatric services (

22,

23). Conversely, the estimated 31% of persons per year accessing psychiatric services in our study is closer to utilization rates among Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans within their first postdeployment year (35%) (

24). This discrepancy in utilization may be explained by previous studies that documented that reservists report greater psychiatric service need than their active duty counterparts (

24,

25). Also, our data collected between 2008 and 2012 may have been affected by the implementation of recent Department of Defense initiatives aimed at increasing psychiatric service use among soldiers (

26,

27), which would not have affected previous military service rates based on 2008 data (

22).

Second, our finding that persons with substance use disorders had the lowest annualized rate of psychiatric service use and that this was the only class of psychiatric disorder not predictive of current service use is supported by existing literature (

12). Persons with substance use disorders often fail to perceive a need (

13,

28,

29) and do not seek treatment until their disorder creates difficulties in daily living (

12,

30) or begins to affect several areas of their lives (

31). In two different national surveys, about 10% of persons with alcohol use disorders perceived a need for treatment and did not seek treatment, whereas a majority of those who perceived a need received treatment (

28). Conversely, that study showed that persons with mood disorders tended to experience several factors that increased their perceived need for services.

Although drug use disorders are uncommon in the military, untreated alcohol use disorder has been of considerable concern since the publication of several reports documenting that military personnel report heavy drinking at consistently higher levels than similar civilian samples (

32,

33). Further, reservists who face combat exposure during deployment are at increased risk of new-onset alcohol misuse and abuse compared with active duty personnel (

34). Although over one-third of National Guard members have been documented to meet criteria for alcohol misuse (

35), less than 1% of service members are referred to substance abuse treatment (

4). In addition, a recent report documented that about a third of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom service members receiving health care from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs who met criteria for risky drinking were advised by a provider to drink less or to stop drinking (

36). Although the negative repercussions of alcohol misuse in the military have been well documented, these studies suggest that recognition of and referral for alcohol use disorders remain insufficient.

Third, our observation that current mood disorder diagnosis was the most significant predictor of recent psychiatric service use is consistent with both military and civilian literature (

11,

13) and may be due to the effect of these disorders on disability, productivity, and health-related quality of life (

3,

37). Further, an increasing percentage of Americans have been seeking services for depression over the past two decades, which may be attributed both to increased population awareness of the signs and symptoms of mood disorders and of pharmacotherapy options for treating them and to reduced negative public perceptions about persons who experience depression (

38,

39).

Fourth, we found that psychiatric service use was not affected by sociodemographic or military characteristics when we adjusted for current and lifetime psychiatric disorder and treatment history. This finding is contrary to a recent U.S. Army report documenting that female, married, and enlisted personnel were more likely than other soldiers to access psychiatric services (

22). Although McKibben and associates (

22) documented an association between demographic variables and psychiatric service use, self-reported impaired functioning was the strongest driver of service use. Their finding that impaired functioning was the primary driver of treatment, in conjunction with our findings, suggests that the military environment may serve as a foil to racial (

12,

40), gender (

12,

40), age-related (

13,

40), and marital status (

12,

40) disparities documented in civilian populations, creating a system in the military where disorder status predominates over sociodemographic factors as a central driver of care seeking.

The results should be interpreted within the context of four limitations. First, self-report data may result in the underreporting of psychiatric symptoms. Even though military personnel are likely to provide truthful answers if they believe individual answers will remain confidential and the findings will be used for legitimate purposes (

41), the presence or perception of stigma toward psychiatric illness (

42) and a bias against reporting embarrassing behaviors (

43) remain prevalent in the military. We compensated for this concern prior to participants’ volunteering for the study by assuring them, both verbally and in writing, that answers would remain confidential and by having all assessments conducted in neutral locations by civilian clinicians without the presence of military personnel.

Second, self-report of service utilization is unreliable (

44). Although administrative records would have provided more reliable treatment information, we assessed participants annually to reduce the time between interviews and to limit recall concerns (

45). Further, interviewers were trained to probe about the purpose, dates, and reasons for psychiatric service use to improve details.

Third, we assessed any psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy contact for self-perceived psychiatric health concerns, which included OTC medication, but we did not assess effectiveness or validity of treatment modalities. Although OTC medication use was rare (N=7), several studies have documented that people seeking psychiatric services do not receive minimally adequate treatment, often having only one visit with providers in the general medical sector (

12). Although this topic is of interest, it was outside the scope of this report and will require further investigation with future studies. In addition, respondents may have sought care for reasons other than the diagnosed disorder. Although this is an area for future investigation, the analysis we performed prevents us from suggesting whether a causal mechanism exists between disorder diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

Fourth, these findings may not be generalizable to other reservists (for example, Navy Reserves) from other states. Although the OHARNG is similar in several key demographic and social factors to the U.S. Army (including percentage of high school graduates and per capita income) and National Guard (including age, gender, and rank) populations, replication of findings in other states and components would improve confidence in our findings.