Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed childhood mental disorders in the United States (

1). From 2003 to 2011, parent-reported diagnostic prevalence of ADHD among children ages four to 17 in the United States increased from 7.8% to 11.0% (or 42%) (

2). State-level changes dramatically varied, ranging from a decrease of 22% (from 7.2% to 5.6%) in Nevada to an increase of 98% (from 7.9% to 15.7%) in Indiana.

Children with ADHD often face long-standing problems with academic achievement, social relationships, life skills, and independence (

3–

6). Only two evidence-based classes of interventions for childhood ADHD exist: medications (stimulants, along with approved alternatives, such as atomoxetine) and a variety of reward-based behavioral interventions (including direct contingency management, parent training, and school consultation) (

3,

7,

8).

Since 1992, many states have implemented public school reforms that link standards and assessments of achievement to accountability systems, including rewards and sanctions (

9,

10). Before enactment of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, 30 states had enacted such consequential accountability reforms (

11). In 2002–2003, NCLB effectively resulted in the remaining states’ adoption of consequential accountability, because sanctions apply to schools that receive Title I funds (

10). NCLB not only requires schools to show adequate yearly progress toward proficiency in reading and math among all children but also targets historically low-performing subgroups of children, including economically disadvantaged children, to show such progress (

12).

Children with ADHD show substandard academic achievement (

13,

14). Consequential accountability may indirectly result in more ADHD diagnoses, because diagnosed children are often treated with prescription medications, which are associated with small increases in standardized achievement scores (

15), albeit with mixed evidence for improvements in school grades and grade retention (

16). In addition, school districts are motivated to promote diagnoses, such as ADHD, to gain testing accommodations or even to exclude such children from formal academic testing, even though the latter became more difficult with implementation of NCLB (

17–

19). Previous research has found mixed evidence regarding the link between consequential accountability and ADHD diagnoses, potentially because the studies relied on single cross-sections of data, limiting their validity. Two studies found a positive association (

20,

21), whereas another study did not (

22).

Because of concerns that schools wield too much influence in mental health diagnostic and medication decisions, including ADHD, 14 states enacted so-called “psychotropic medication laws” between 2001 and 2009 (

23–

27), which typically direct public school boards to adopt policies to prohibit school personnel from one or more of the following: recommending that a child take a psychotropic medication, requiring that a child take a psychotropic medication as a condition of enrollment, or using a parent’s refusal to medicate the child as the sole basis for an accusation of neglect. Under these laws, fewer ADHD diagnoses should occur, because medication prescriptions are normally based on a diagnosis (

28). Two studies did not find an association between these laws and ADHD diagnoses; however, they were based on 2003 data, when only a few states had enacted such legislation (

21,

22). [A figure in the

online supplement reveals which states were first exposed to consequential accountability reforms via NCLB (20 states and the District of Columbia) and which states have enacted psychotropic medication legislation (14 states); five of these states experienced both.]

Our objective was to use a difference-in-differences research method with repeated cross-sectional data to test the following hypotheses: ADHD diagnostic prevalence would be positively associated with NCLB-initiated school consequential accountability reforms among low-income children, and ADHD diagnostic prevalence would be negatively associated with psychotropic medication laws that prohibit public schools from recommending or requiring medication use. We tested these hypotheses together because these state-level factors could have had a simultaneous effect and because five states experienced both factors. Our study design improved on previous studies that relied on single cross-sections of data (

20–

22).

Methods

Data

The child-level data were repeated cross-sections from the U.S. and state-representative 2003–2004 (hereinafter, “2003”), 2007–2008 (hereinafter “2007”), and 2011–2012 (hereinafter “2011”) National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), which were collected with informed consent and included 37,082 children ages six to 13 attending public school in wave 1, 32,413 in wave 2, and 35,987 in wave 3 (

29–

31). Each wave was state-stratified with approximately equal sample sizes from each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Our study did not require institutional review board approval, because it used secondary data from publicly available sources.

Outcome Variable

The outcome variable was whether a child had ever received a diagnosis of ADHD, based on whether a physician or other health care provider ever told the survey respondent (usually the child’s parent or guardian) that the child had ADHD or attention-deficit disorder (hereinafter, ADHD). Diagnostic prevalence consistency between NSCH parental reports and review of medical records was found in a sample of children from Southern California (

32).

Statistical Analysis

The NSCH includes three repeated cross-sections, allowing for a difference-in-differences (DiD) research design that reduced the potential for bias by controlling for baseline ADHD diagnostic prevalence differences between groups of states and by controlling for national prevalence trends across all states (

33). Each statistical model used two NSCH waves and included two DiD terms. The first DiD term was the interaction between two binary variables: NCLB-initiated consequential accountability and the later NSCH wave. The parameter estimated the association between changes in ADHD diagnostic prevalence and NCLB-initiated consequential accountability by comparing how the diagnostic prevalence changed between two NSCH waves in states that had consequential accountability initiated by NCLB versus states that had consequential accountability prior to NCLB.

The second DiD term also involved the interaction between two binary variables: psychotropic medication law and later NSCH wave. The parameter estimated the association between changes in ADHD diagnostic prevalence and state psychotropic medication laws by comparing how the diagnostic prevalence changed between 2003 and 2011 in states that had a psychotropic medication law versus states without such a law.

We estimated four logistic regression models, because the ADHD diagnosis outcome variable is binary. The first three models focused on NCLB-initiated consequential accountability, and we analyzed the 2003–2007 (model 1) and the 2007–2011 (model 2) periods separately, as well as the entire 2003–2011 period (model 3), because we did not expect the same results under NCLB and Race to the Top after 2009. Race to the Top is an education initiative within the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 that provides federal funds to states aiming to spur reforms and innovations within their public school systems. These models included children only in households with incomes ≤185% of the federal poverty level (FPL)—the income eligibility threshold for the National School Lunch Program’s free or reduced-price meals—because we believed these children would be most affected by NCLB for the following reasons. First, low income is correlated with NCLB’s focus, low academic proficiency (

34). Second, school districts use National School Lunch Program enrollment data as a proxy to identify economically disadvantaged children under NCLB, to determine whether this subgroup is making adequate yearly progress toward academic proficiency (

35). Third, NCLB sanctions apply only to schools that receive federal Title I funds (

12), and although the NSCH does not identify which children attend Title I schools, school districts often measure school-level poverty for Title I purposes using National School Lunch Program eligibility (

35).

Model 4 focused on psychotropic medication laws from 2003 to 2011 and included children at all income levels. The model excluded children in Alaska, Florida, Louisiana, and Tennessee because laws in those states became effective after the 2003 NSCH data collection ended in July 2004 (

29).

In all four models, we included children ages six to 13 who were attending public school, with the rationale that 88% of diagnosed 17-year-old children attending public school had received their diagnosis by age 13. NCLB requires annual assessments in grades 3–8, when children are approximately eight to 13 years old, and NCLB may have affected younger children who were preparing for these assessments.

The 2011 NSCH was the only wave to report the age at which a child first received an ADHD diagnosis. Therefore, in models 2–4, we excluded children who were diagnosed before the first NSCH wave used in the model, as well as children diagnosed before age 5, the age for public school entry. Therefore, for the 2011 NSCH, 61.8% (model 2), 29.4% (model 3), and 23.1% (model 4) of children with ADHD diagnoses were excluded. If these children were included, their diagnoses would have been counted as having occurred between the two NSCH waves being analyzed, when, in fact, they were diagnosed either before the first NSCH wave or before attending public school, potentially biasing the DiD estimate. This restricted sample was representative of the 2011 NSCH public school children who were at risk of being diagnosed after the first NSCH wave used in the model. Regardless, for curiosity, we reestimated each model without their exclusion.

To account for changes in health care and sociodemographic characteristics between survey waves, and using methods similar to those of other ADHD investigations (

20–

22,

36,

37), we included the following covariates in each model: number of health care providers (and their ages) per capita by state (

38–

40); child’s gender, age, race, and health insurance status; family parental structure; number of children in the household; household income; highest education level of household; and primary language spoken in the home.

In a logistic regression model, the DiD parameters represent the ratio of two odds ratios. We transformed these results into more interpretable probabilities by estimating average marginal effects (

41). [The appendix in the

online supplement provides details.]

The models were estimated with Stata 12 (

42), which incorporated NSCH sampling weights, with standard errors estimated by clustering at the state level to account for potential serial correlation or unobserved, random state-year shocks (

43). In a logistic regression model, the interaction effect of two interventions (in other words, the cross-derivative) does not equal the marginal effect of the interaction term (

44). However, both DiD interaction terms included only a single intervention variable (that is, NCLB-initiated consequential accountability or psychotropic medication law); therefore, each interaction effect equaled the marginal effect of the DiD interaction term, because the interaction effect was identified from the DiD of the observed outcome under intervention minus the DiD of the potential outcome under nonintervention (

45,

46).

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the 2003, 2007, and 2011 NSCH analytical samples for children ages six to 13 attending public schools. From 2003 to 2011, the diagnostic prevalence of ADHD increased 37% (from 8.6% to 11.8%), similar to the 43% increase (from 9.7% to 13.8%) when the analytic sample included children only from households with incomes ≤185% of FPL. (Numbers presented in the text and tables are rounded, but calculations are based on more precise numbers.)

Table 2 presents results for our four ADHD diagnostic prevalence logistic regression models. Models 1, 2, and 3 estimated the association between ADHD diagnostic prevalence and NCLB-initiated consequential accountability for children ages six to 13 from households with incomes ≤185% of FPL in 2003–2007, 2007–2011, and 2003–2011, respectively. The DiD parameter estimates of 1.38 (p<.05) in model 1 and .92 (p=.61) in model 2 represent the ratio of two odds ratios. We transformed these results into more interpretable probabilities by estimating average marginal effects (

Table 3).

Table 3 reports unadjusted and adjusted ADHD diagnostic prevalence estimates. For example, for each child in model 1, four predicted diagnosis probabilities were estimated with the model’s results, by using each combination of 0–1 values of NCLB-initiated consequential accountability and NSCH wave variables; the child’s other covariates retained their actual values. From 2003 to 2007, children ages six to 13 in households with incomes ≤185% of FPL residing in states first exposed to consequential accountability through NCLB had an adjusted ADHD diagnostic prevalence increase of 56% (from 8.5% to 13.2%), but demographically similar children residing in states that had consequential accountability prior to NCLB had their adjusted prevalence increase by 19% (from 10.2% to 12.1%). This pattern resulted in a DiD average marginal effect of 2.8 percentage points (p<.05): (13.2% − 8.5%) – (12.1% −10.2%). From 2007 to 2011 (model 2), the DiD average marginal effect was the reverse, decreasing by .8 percentage point, but was not statistically significant.

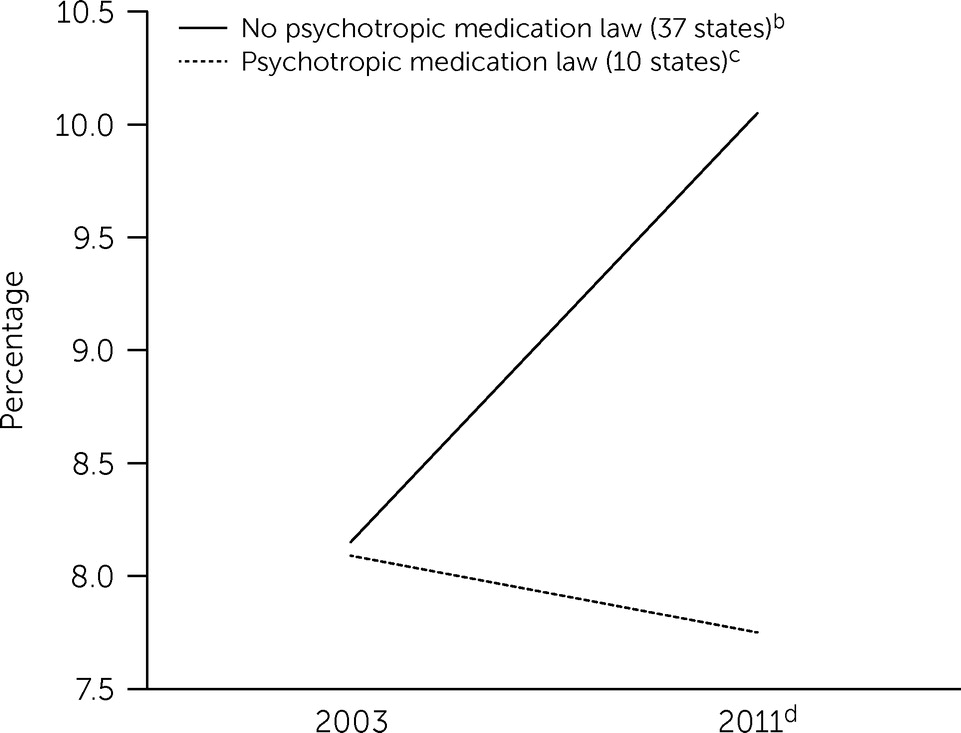

The key DiD parameter in model 4 was used to estimate the association between changes in ADHD diagnostic prevalence and state psychotropic medication laws, and the result was .75 (p<.05). We transformed this ratio of two odds ratios into a more interpretable probability by estimating an average marginal effect in

Table 4, which reports unadjusted and adjusted ADHD diagnostic prevalence estimates. For each child, four predicted diagnosis probabilities were estimated with the results of model 4 by using each combination of 0–1 values of the psychotropic medication law and NSCH wave variables; the child’s other covariates retained their actual values. From 2003 to 2011, children ages six to 13 residing in states with a psychotropic medication law had their adjusted prevalence decrease 4% (from 8.1% to 7.8%), but demographically similar children residing in states without a psychotropic medication law had their adjusted prevalence increase by 23% (from 8.1% to 10.1%). This pattern resulted in a DiD average marginal effect of −2.2 percentage points (p<.05): (7.8% − 8.1%) – (10.1% − 8.1%) (

Figure 1).

Discussion

State education-related policies have differential implications for ADHD diagnostic prevalence. From 2003 to 2007, public school children from low-income households residing in states first experiencing consequential accountability under NCLB showed a marked increase in adjusted ADHD diagnostic prevalence of 56% (from 8.5% to 13.2%), far outpacing the increase of 19% (from 10.2% to 12.1%) of demographically similar children residing in states that had consequential accountability prior to NCLB. These results may stem from NCLB’s requirement for economically disadvantaged children to make adequate yearly progress toward academic proficiency as well as its sanctions that apply only to schools that receive Title I funds. From 2007 to 2011, however, this association did not persist, because, we suspect, the short-term response to NCLB was greater and because the introduction of the Race to the Top in 2009 led to a different set of incentives. The 2003–2007 association is consistent with findings from previous studies (

20,

21) but differs from a study that did not find an association (

22). However, these studies relied on single cross-sections of data, limiting their validity.

Consequential accountability reforms provide incentives for teachers to address and refer children having academic difficulties, which may be improved by medication use for children with ADHD (

15,

16). Among low-income children, ADHD diagnoses may be appropriate to compensate for a lack of school resources, including larger class sizes and fewer mental health behavioral services. However, concerns may be warranted that some of these diagnoses were not based on careful assessments, given low-income children’s limited access to specialists (

36,

47).

For the period 2003–2011, states with psychotropic medication laws that prohibit public schools from recommending or requiring use of medication appeared to provide a headwind against the national trend of increasing ADHD diagnostic prevalence. The adjusted prevalence slightly decreased by 4% (from 8.1% to 7.8%) in these states, in contrast to the 23% increase (from 8.1% to 10.1%) in states without such laws. Under these laws, diagnoses would also be likely to decline, because a prescription is typically based on a diagnosis (

28). These laws may reduce inappropriate diagnoses, but because teachers and other school personnel are often the first to suggest the diagnosis of ADHD for children (

3,

48), these laws may also lead to lack of appropriate assessment for ADHD among some children.

Although DiD models using repeated cross-sections comprise a powerful research design in an observational study, results of this study could be biased if another intervention occurred contemporaneously with NCLB or state psychotropic medication laws that was also associated with ADHD diagnoses, such as programs that integrate mental health care into primary care settings (

49). To address this potential limitation, we used a falsification test and reestimated models 1 and 4 (the key results) including only privately schooled or home-schooled children, who are not explicitly covered by NCLB and state psychotropic medication laws. The key results became nonsignificant, providing support that no contemporaneous policy was evident.

As a further test, we reestimated model 1 by analyzing the interaction of the DiD term—NCLB-initiated consequential accountability and later NSCH wave—with a binary variable indicating whether the child’s household income was ≤185% of FPL, which created a difference-in-differences-in-differences (DiDiD) term. The average marginal effect of the DiDiD parameter was 4.0 percentage points (p<.01), meaning the relative change in adjusted diagnostic prevalence between low-income and high-income public school children was 4.0 percentage points higher for children residing in states first exposed to consequential accountability through NCLB. This model corroborated the key finding in model 1 and reduced the potential for state-level confounders.

A child’s age at diagnosis was reported only in the 2011 NSCH, which was not used in the 2003–2007 analysis (model 1). Some diagnoses reported in the 2007 NSCH may have occurred before the 2003 NSCH, so these children were not actually diagnosed during the 2003–2007 period. We reestimated model 1 by including only children ages six through nine, reducing the probability that the children surveyed in the 2007 NSCH had been diagnosed prior to 2003, when they would have been ages two through five. The DiD average marginal effect estimate was 3.7 percentage points (p<.05), corroborating the key result in model 1.

To satisfy curiosity, we reestimated models 2–4 without excluding any 2011 NSCH diagnosed children (see Methods section). The statistical significance of key DiD results did not substantively change; that is, they remained statistically significant at the .05 level or remained nonsignificant because these previously excluded children’s residence states were not sufficiently associated with states that had NCLB-initiated consequential accountability or psychotropic medication laws.

Finally, each NSCH wave contained a supplemental data set with five imputed household income values. We reestimated model 4 using multiple imputation, reducing the missing rate from 11% to 5%; the key result did not substantively change. Multiple imputation could not be used for models 1–3, because the method does not work for a variable that is used to subset the data—in our case, household income—so these models had remaining missing rates of 3%−5%.

Conclusions

NCLB-initiated consequential accountability reforms were associated with more ADHD diagnoses among low-income public school children, consistent with increased academic pressures from NCLB, requiring adequate yearly progress toward academic proficiency for this subgroup. In contrast, psychotropic medication laws that prohibit public schools from recommending or requiring medication use were associated with fewer ADHD diagnoses, as these prohibitions may indirectly reduce diagnoses. Future research should investigate whether children most affected by these policies are receiving appropriate diagnoses or are being overdiagnosed because of NCLB consequential accountability or underdiagnosed because of psychotropic medication laws.