The first few years after psychosis onset presage much of the eventual morbidity in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, including suicidality (

1), functional losses related to relapse and hospitalization (

2), violence (

3), and the onset of other potentially modifiable prognostic factors, such as substance misuse and social isolation. Several pharmacologic and psychological interventions have been shown to improve outcomes (

4) during this critical “window of opportunity” for ameliorating long-term disability (

5). Of particular promise are comprehensive first-episode services (FES) with teams that integrate and adapt the delivery of empirically based treatments to younger patients and their families (

6).

FES programs have received strong support in Europe, Australia, and most notably the United Kingdom, where a national implementation strategy has been in place since 2000. Policy debates outside the United States have matured from questions about efficacy (can intensive FES models work?) through effectiveness (how well do FES models work in usual settings?) to implementation models (how can improvements in trials be sustained in the real world?) (

7) and health-economic analyses (

8). Accumulating results validate a “best available evidence” (

9) argument for funding and implementing FES models as platforms to deliver needed care while investigating their value (

10) for a particular health care system.

Significant uncertainty remains, however, about the feasibility and impact of FES in the fragmented U.S. health care system, wherein deployment has required creative approaches to resourcing (

11) that limit scale. Meanwhile, chronic psychotic disorders are the leading contributor to mental illness expenditures in the United States ($62.7 billion in 2002). Much of direct health care costs are attributable to psychiatric hospitalization, but a larger proportion (64%) arises from indirect costs related to reduced vocational functioning. Demonstrating the effectiveness of a nationally relevant FES model can address the status quo.

The clinic for Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP) was established in 2006 within a public-academic collaboration (

12). The guiding question for the study reported here was, Can an FES program in the U.S. public sector meaningfully improve outcomes for individuals early in the course of a psychotic illness? We hypothesized that STEP would be more effective than usual services as measured by the primary outcome of psychiatric hospitalization and a range of secondary measures related to community functioning, with a focus on vocational engagement. We report one-year outcomes of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of STEP versus usual care in a real-world U.S. setting.

Methods

Setting and Design

STEP is located within the Connecticut Mental Health Center (CMHC). The center serves a catchment of about 200,000 persons eligible for public-sector care in the greater New Haven area. CMHC has an average daily census of 2,500 active outpatients receiving care for a variety of serious mental illnesses, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. The Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS) owns the facility and hires most of the clinical staff. DMHAS collaborates via a staffing contract with the Yale Department of Psychiatry that provides psychiatrists, psychologists, and administrative staff for the center.

A “pragmatic” randomized controlled design (

13) was employed to include a broad, relevant sample; intervene within the resources of a community mental health center with an ecologically salient comparator; and collect data on clinically relevant outcomes. To test the value of FES, DMHAS in discussions with the principal investigator in 2006 agreed to waive three customary exclusions for care at CMHC. Thus patients experiencing early psychosis who were eligible for this study and who were randomly assigned to STEP care were offered services at the CMHC even if they were privately insured, lived outside the center’s statutory catchment area, or were under 18 years old.

Sampling

The study recruited participants from April 2006 to April 2012, and all assessments were concluded in May 2013 to allow for at least one year of follow-up for all enrollees. Recruitment efforts were limited to informing local hospitals, emergency departments, and community clinics; making invited presentations to professional groups; and regularly visiting the largest regional private, nonprofit psychiatric hospital.

We included all individuals between the ages of 16 and 45 who were within five years of onset of a psychotic illness, who had not received more than 12 weeks of treatment with antipsychotic medications in their lifetime, and who were willing to travel to STEP for treatment. Minimal exclusions were as follows: patients whose psychosis was confirmed as secondary to a general medical disease, an affective disorder, or a substance use disorder; and patients with severe cognitive (IQ <70) and functional limitations that qualified them for care from the Department of Disability Services.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants per procedures of the study protocol approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board.

Allocation

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to STEP or to treatment as usual by permuted and concealed random blocks between 2 and 5. The research statistician independently generated the random sequence kept in sealed envelopes. After a participant gave consent, research assessors contacted the statistician to open the next envelope and allocate the participant.

Interventions

STEP.

The FES followed best practices and tailored interventions with established efficacy to the needs of younger patients and their families (

14). Patients were allowed to choose from a menu of options that included psychotropic medications, family education, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and case management focused on brokering with existing CMHC-based services for employment support and with area colleges for educational support. Family education was delivered with combinations of multifamily group and individual family sessions. CBT principles informed group and individual approaches. Although academic psychologists initially led family and CBT groups, a train-the-trainer approach transitioned leadership to clinical staff coleaders. In keeping with the pragmatic ethos, clinician time was reallocated from existing ambulatory services. The team consisted of staff and trainees from psychiatry, psychology, social work, and nursing. Collaborative team management allowed interventions to be offered in a manner targeting patient and family needs but rested finally in patient choice. The FES implementation has been described in published protocols (

15,

16), and manuals are available upon request.

Treatment as usual.

Patients randomly assigned to usual treatment either continued treatment with existing outpatient providers or were referred on the basis of health insurance coverage. For referrals to the study from inpatient units, eligibility assessment and allocation were completed before discharge to preclude any treatment disruptions, especially for those allocated to usual treatment. Given the pragmatic nature of the design, no treatment guidelines were provided to the community practitioners, but utilization by participants of the various treatments was assessed. The relatively few patients who were randomly assigned to usual treatment and who were eligible for public-sector care at CMHC (N=8) were referred per routine practice to one of the ambulatory teams at the center.

Assessments

Assessments were scheduled every six months. By using assessors independent of the treatment team, we minimized measurement bias, but blinding them to the intervention arm was not feasible. Commonly employed instruments assessed psychiatric diagnosis (

17), symptoms (

18,

19), suicidality (

19), substance use (

20), and functioning (

21,

22). Duration of untreated psychosis was derived as the time in months between onset of psychosis defined by the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (

23) scale and initiation of antipsychotic treatment.

Hospitalization outcomes were determined from structured in-person and telephone interviews of participants, family members, and referral sources, along with review of available medical records. We supplemented these sources by querying administrative data from the largest provider of inpatient services in the region, Yale Psychiatric Hospital (YPH). Employment, school, and housing status and information about general social functioning were assessed with the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) (

24), and treatment utilization was assessed with the Services Utilization and Resources Form (

25). We report modified U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics vocational categories (

26) as follows: employed (in a full- or part-time job, in school, or filling parental or homemaker roles), unemployed

(jobless, looking for a job, available for work, or in supported employment), and not in the labor force (any lack of capability to work or less than frequent attempts at finding work as measured by the SFS). Each category was assessed over the prior week. Those who were employed or unemployed were considered “vocationally engaged.”

Analysis

A modified intention-to-treat analysis was conducted for the primary outcome of hospitalization. After randomization, we excluded only patients who withdrew consent for study participation. Hospitalization data were obtained for all remaining 117 participants from interviews or YPH administrative records. [A recruitment flowchart is available in an online data supplement to this article.] Other measures could be collected only for participants who were available for in-person or structured phone assessments. When six-month data but not 12-month data were available for vocational functioning, the six-month results were carried forward. We evaluated the validity of this carry-forward assumption. For patients with complete data, those who were vocationally engaged at six months retained this status at 12 months (93%). [A table presenting results of this analysis is included in the online supplement.]

Logistic regression (for categorical measures) and linear regression (for continuous measures) were used in models that included one-year outcomes for the dependent variables of hospitalization and vocational engagement. Effects on global functioning and symptoms were assessed with analysis of covariance. We planned to include additional baseline covariates in the models when they were significantly correlated (p<.05) in the combined samples that included STEP plus usual treatment with the 12-month outcome. No variables of interest qualified for such inclusion.

Results

Recruitment Experience

Between April 2006 and April 2012, we received 512 requests for information, of which 491 potential participants were screened by phone for eligibility. A total of 284 were excluded, including 161 (57%) for excessive length of treatment or illness duration, 53 (19%) for a nonpsychotic illness, 19 (7%) who were too young, 16 (6%) who subsequently refused further contact, 13 (5%) who were unwilling to be treated at CMHC, 12 (4%) who were subsequently unreachable, six (2%) who were on legal probation, two (1%) who moved out of the state, and two (1%) who were monolingual Spanish. Of the 207 who completed a full in-person eligibility assessment, two were deemed ineligible and 29 were provided STEP care without randomization in an initial pilot (data not included).

We were able to enroll 120 of the remaining 176 patients. After randomized allocation, one patient from each arm withdrew consent, voicing delusional concerns about study participation. In addition, one minor was withdrawn by a parent disappointed by allocation to usual treatment. Subsequent attrition of participants was equivalent in both arms. Two patients relocated out of state with their families, and another three were incarcerated for offenses committed before study entry and were unavailable for further assessments. Four additional participants were referred out of STEP after appropriate diagnostic revision (two each for bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder), and they subsequently declined assessments.

Study Sample

The study recruited a diverse, young, and preponderantly male sample, with a long and variable duration of untreated psychosis (mean 10±15 months) and evidence of significant clinical distress and functional loss, comparable to samples in similar trials (

27,

28) (

Table 1). Specifically, almost one in ten had attempted suicide; Global Assessment of Functioning and Heinrich’s Quality of Life Scale scores indicated significant socio-occupational dysfunction. Almost half had a comorbid substance use disorder (excluding nicotine use), and more than a quarter met

DSM-IV chronicity criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Notably, more than eight of every ten patients entered treatment via an acute emergency or inpatient setting, with moderately severe psychosis symptoms and after typically brief hospitalizations (three to five days). The two groups were broadly comparable on baseline measures (

Table 1).

Effectiveness Outcomes

YPH administrative data effectively supplemented information from interviews with patients and their families and from referring clinicians and medical records. Patient and caregiver reports detected the large majority of YPH hospitalizations at baseline, but only just over half of such hospitalizations during follow-up. Unfortunately, equivalent records were not available for other hospitals, and patient and caregiver report data suggested that those in the usual-treatment group were more likely to be hospitalized away from YPH during follow-up. [Tables in the online supplement present data on hospitalizations.] This is not surprising, given that those receiving STEP care were more likely to be referred to the closest hospital (that is, YPH), whereas those assigned to care elsewhere in the community would not experience this referral preference. In summary, although data from YPH records made our hospitalization outcomes more comprehensive, the data likely biased measurement toward more hospitalizations in the STEP group and led to a conservative estimate of the effectiveness of STEP care in reducing psychiatric hospitalization.

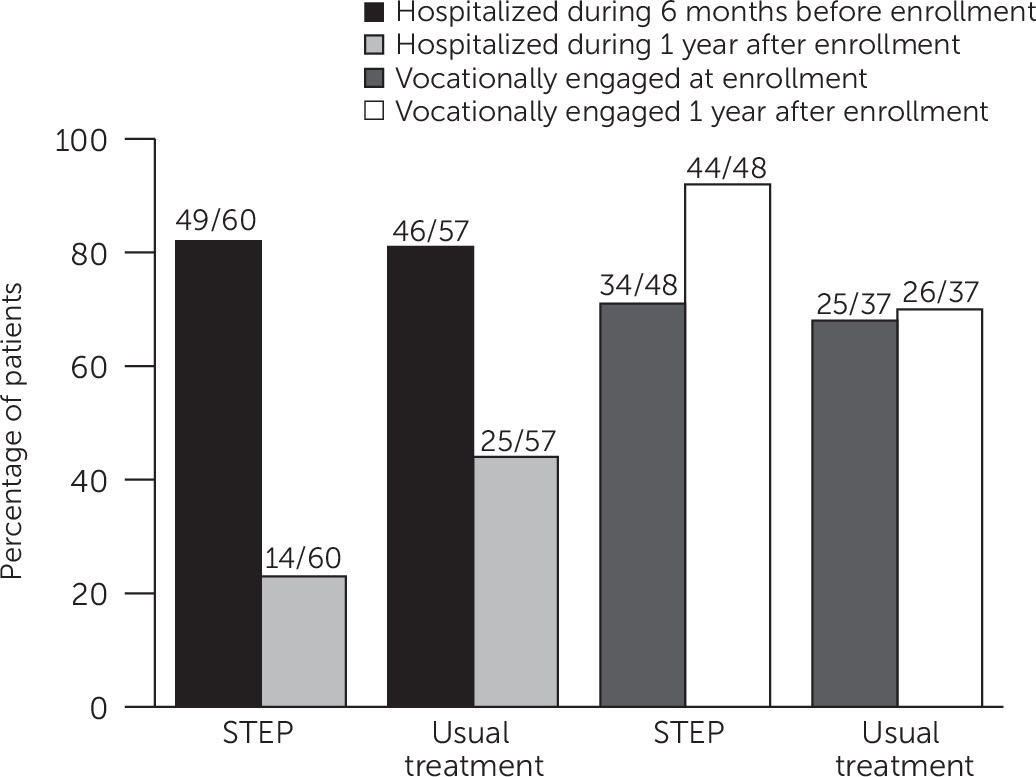

Patients allocated to STEP care had better outcomes on all measures of hospital utilization (

Table 2). STEP care resulted in fewer total hospitalizations (20 versus 39 with usual treatment) and a lower likelihood of hospitalization (14 of 60 [23%] patients versus 25 of 57 [44%] of those in usual treatment). These data translate to a number needed to treat (NNT) of five—that is, for every five patients allocated to STEP rather than usual care, one additional patient avoided psychiatric hospitalization over the first year. This difference was not attributable to a few high utilizers of hospital care in the usual-treatment group [see table in online

supplement]. When hospitalized, patients allocated to STEP care averaged more than six fewer hospital days than those in usual treatment. The STEP cohort also accounted for fewer bed-days over the year (246 versus 495 with usual treatment).

These reductions in hospital utilization were accompanied by improved vocational outcomes. Although we were able to analyze data for only the subset of patients who were available for in-person or phone assessments, about nine of every ten patients allocated to STEP care were classified as vocationally engaged at follow-up versus about six of every ten of those allocated to usual treatment (

Table 2). Although at study entry patients allocated to usual treatment were more likely to be employed or in college or high school at least part-time (

Table 1), this advantage reversed within one year (

Table 2 and

Figure 1).

STEP patients were more likely to be in contact with outpatient mental health services and showed improvements in a variety of measures of community functioning and symptoms (

Table 3), consistent with their statistically more robust advantages in hospitalization and vocational engagement outcomes.

Discussion

This is the first randomized trial of an FES program in the United States. It demonstrated the effectiveness of a public-sector model of early intervention for psychotic illnesses. STEP care reduced hospital utilization and improved vocational functioning within the first year of enrollment. Almost nine of every ten patients entered the study from an acute care setting; however, more than three-quarters of STEP patients avoided hospitalization over the first year of treatment, compared with a little over half of those allocated to usual treatment. Patients in usual care were more likely to drop out of the labor force (33% versus 8% in STEP).

Several design features are relevant to the interpretation of this study. As a pragmatic trial, it retained the benefit of randomization for unknown prognostic variables while ensuring ecologic validity in the three fundamental domains of patients, interventions, and outcomes (

29). First, wide inclusion criteria with minimal barriers to entry recruited a sample representative of the types of patients who usually present for care at this site. Second, the model of care was implemented within the resources of a public-sector ambulatory service and compared with a relevant alternative. Finally, outcomes of greatest pragmatic relevance to the system of care were collected over a period of meaningful duration. All of these aspects speak most directly to managers of limited health care resources who are contemplating the value of FES.

The setting of this study is key to evaluating its generalizability. CMHC is part of a nationwide network of state agencies that was established under the federal Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963. As we have argued previously (

12), these public-sector agencies were previously molded by efforts to deinstitutionalize persons with chronic illness, and they now provide an excellent national platform for early intervention. Also, although full implementation of the Affordable Care Act will expand Medicaid coverage and subsidize private coverage via health insurance marketplaces, payment and expertise for services classified as nonmedical, such as the rehabilitative services essential for FES, will likely continue to reside within these state agencies (

11).

We recognize several limitations. First, the pragmatic design with broad eligibility and office-based care lowered barriers to entry but also engendered loss to treatment and follow-up in a population well known to be difficult to retain (

30,

31). The related attrition from in-person assessments, while comparable to that in other seminal trials (

28), limited statistical power to resolve secondary outcomes. Although we were able to successfully recover hospitalization data from the dominant local provider, this likely biased data collection toward more hospitalization events in the STEP group. We thus expect actual effectiveness of FES in reducing psychiatric hospitalization to be greater than reported here.

Second, although this design addressed the question of whether and how much benefit was derived from an FES program compared with the actual choices patients face in usual care, it cannot resolve questions about which elements of the model were crucial to its success. STEP care was assembled from treatments with established efficacy, and treatment utilization measures were designed for health economic analysis focused on the number, provider type, and setting of health care visits; but fidelity was not assessed. Also our model of care deliberately envisioned the variety and dose of treatment components to vary with patient need and choice, which would confound any causal inferences between type of treatment received and outcome. With these caveats, there was no clear difference in choice of medications between groups; however, there was likely increased outpatient contact in STEP (27.6 versus 18.9 visits per patient for usual treatment over the first year [see table in the online supplement]). Also we suspect, but cannot prove, that the content of usual care in the community was less inclusive of family education and CBT approaches. In summary, STEP care was qualitatively and quantitatively different from usual care, but determination of which elements were pivotal to better outcomes is beyond the scope of this study design. Health economic evaluation of the relative costs and benefits based on quantitative utilization estimates will be presented in a future report.

These results are broadly consistent with those of other studies of integrated care for early psychosis (

32) but add a vital component to our knowledge base. The three seminal randomized trials of FES conducted in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Norway (

27,

33,

34) used community-based teams with patient-to-clinician ratios of 10:1 to 12:1. In comparison, STEP is more generalizable to U.S. community settings, with average patient-clinician ratios of 50:1 and office-based care. Although the long history of public-academic collaboration makes CMHC a somewhat unique environment for service innovation (

35), reports from Massachusetts, California, and North Carolina (

36–

38) support the feasibility of implementing similar publicly funded FES programs across distinct and heterogeneous U.S. health care ecologies.