Mental illness is considered more burdensome than most general medical disorders (

1). Its negative impact is compounded by high prevalence and early onset (

1). Nearly 50% of Americans will experience a lifetime mental disorder, and about 75% of adult cases of psychiatric illness have their onset before age 24 (

2). Poor outcomes are exacerbated the longer mental illnesses go undetected (

3). However, promptly treating persons with emerging disorders can mitigate poor outcomes (

4). Thus interest is growing in the potential for early intervention services (EISs) to improve functioning (

5), reduce suicide and hospitalization rates (

6), and prevent the full expression of disorders (

2).

However, most patients do not receive treatment until many years after onset (

3), when more severe symptoms emerge (

2,

7). Attitudinal and structural barriers, as well as poor insight into the need for treatment, present obstacles to the use of EISs (

8). It is imperative, therefore, that mental health service planners investigate ways to facilitate patient engagement. An empirically demonstrated means of improving engagement is to incorporate patients’ preferences regarding service features (

9,

10). Including patient preferences in EIS design may increase the rates at which individuals use services. Matching patients to their preferred treatments reduces dropout rates and improves outcomes (

9,

11). Thus incorporating preferences in mental health EISs may increase rates of initial contact. However, valid methods for soliciting preferences are needed.

Discrete-choice conjoint experiments (DCEs) are designed to solicit preferences for the features or attributes of health interventions (

12). DCEs use survey methods that pose forced choices between complex service options. By systematically varying the attributes or features of these options, DCEs can estimate the relative value of the individual levels of each attribute and quantify an attribute’s relative importance. DCEs mimic real-world decision making and offer advantages over traditional survey methods (

13,

14). Ratings often produce high scores across attributes, reflecting an individual’s desire for services that encompass all positive characteristics. Resource limitations, however, frequently necessitate trade-offs between attributes (

13). DCEs can also limit the social desirability biases that may compromise preference research (

14). Individuals with severe mental illnesses can complete DCE surveys and make meaningful trade-offs (

15).

The purpose of this study was to use a DCE survey to elicit the views of patients, family members, and mental health professionals about the attributes of an EIS that they believed people with psychiatric illnesses would be most likely to contact. Because a successful program needs to balance the views of users and their families with the views of those who provide services, an understanding of multiple EIS perspectives can inform service design. To ensure uptake and continued engagement, services should incorporate patient preferences (

9,

11). In addition, professionals’ attitudes may affect whether they adopt new practices (

16) and may therefore affect service planning decisions. Areas of agreement could form a foundation for treatment; discrepancies could inform policy changes (

17). To ensure that responses were relevant to those who actually use the EISs, participants were asked to respond to our survey from the perspective of someone seeking mental health treatment for the first time.

The following research questions were addressed. Can respondents be represented by latent classes on the basis of similar EIS preferences, and if so, which attributes exert the most influence on the service use decisions of each class? Do the classes differ in regard to demographic covariates? Three covariates that could influence EIS preferences were examined: background (patients and family members versus professionals) (

17), age (

18), and sex (

19) of the respondents. Moreover, demographic characteristics of each class were compared. Because of the emerging interest in locating mental health services in primary care settings (

20) and the development of new e-health options (

21), simulations were used to predict the percentage of survey respondents likely to use an EIS based in an e-health, primary care, or clinic or hospital setting.

Methods

The St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton Research Ethics Board approved this study. Recruitment occurred between March and October 2011 from six clinics specializing in psychotic disorders, mood and anxiety disorders, and general psychiatric disorders. Participants were also recruited from four youth mental health and primary care clinics in the community

When patients and family members entered the clinic, they were informed of the survey by receptionists. Those who agreed to participate obtained access to the survey on a laptop. Further recruitment was conducted from family support groups organized through local patient advocacy organizations (Schizophrenia Society of Ontario and Mood Menders). Individuals recruited from these groups were not necessarily related to patient participants. Clinic staff were asked to complete the survey via an e-mailed link. All participants provided informed consent via a computer interface before responding to the survey. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete. Upon completion, participants were given a choice of $15 gift cards.

The study design was informed by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research checklists (

22,

23). We reviewed literature to identify attributes that might influence EIS utilization. A multidisciplinary research team, including a peer support representative, reduced the list to 16 actionable four-level attributes with limited conceptual overlap (

22).

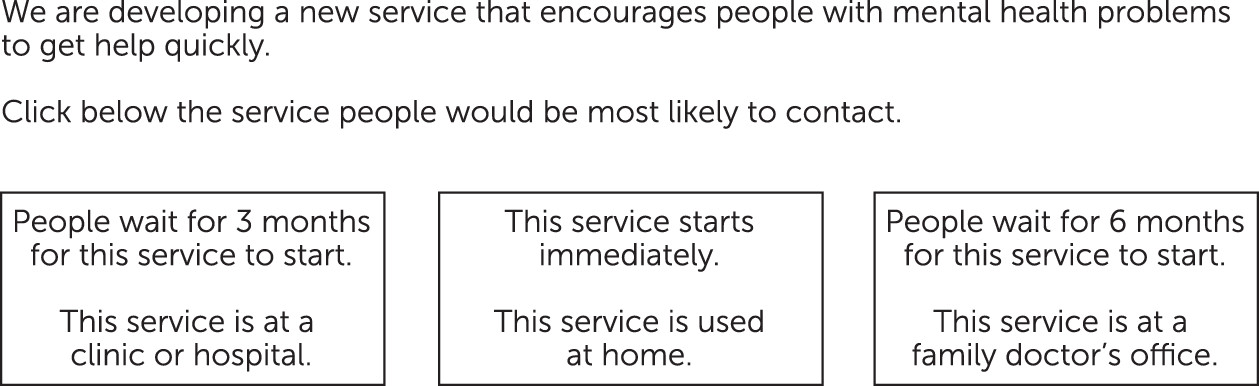

Sawtooth Software’s SSI Web version 7.4 was used to administer the computerized survey (

24). A partial-profile design was employed (

Figure 1) in which forced-choice tasks include subsets of the attribute options (

25,

26). DCEs can be simplified so that individuals with fifth-grade reading skills can reliably complete tasks (

27).

At the beginning of the survey, “mental health problems” were defined in plain language as “a lot of fear and anxiety, a lot of sadness and depression, hearing voices or seeing things that are not there, and/or using too much alcohol or drugs.” In 18 choice tasks, participants chose between three hypothetical EIS options with specific combinations of attribute levels. They were asked to select an option that people with mental health problems would be most likely to contact. The experimental design ensured that each attribute level was presented as close to an equal number of times as possible. Each respondent was randomly assigned one of 999 versions (

22,

24,

28).

The survey was completed by 562 people (249 patients, 92 family members, and 221 professionals). Demographic data was incomplete for 14 participants. The participants ranged in age from 16 to over 55, 71% (N=391) were female, and 83% (N=455) were born in Canada.

Latent Gold Choice 4.5 software was used to analyze the DCE survey data (

24,

29). These tools identify classes with similar preferences and generate zero-centered utility coefficients to determine how strongly each attribute level is preferred. The software forms latent classes, with respondents grouped on the basis of preference similarities (

29). Information criteria were used to determine which maximum-likelihood solution (that is, the ideal number of latent classes) to adopt (

29). Latent-class solutions that included one to five solutions were modeled and replicated ten times from random starting seeds. The choice of a latent-class solution is a balance between fit—denoted by information criteria—and parsimony (

30). The goal was to obtain distinct subgroups from a relatively large sample; thus Bayesian information criteria (BIC) were deemed the most appropriate, consistent with other literature (

30–

32).

Background (professionals versus patient and family members) (

17), age (16–35 versus ≥36) (

18), and sex (

19) were included as covariates. These variables were predicted to influence perceptions of the type of EISs participants would expect people to use (

33). Importance scores, calculated by using the range in utility coefficients (

13), reflect how much effect each attribute has on choice.

Randomized first-choice (RFC) simulations predict how participants would respond if new multiattribute service options were introduced (

34–

36). The utility coefficients derived from the survey allowed RFC simulations to be computed (

24). The goal of these simulations was to explore emerging health care options that might encourage early utilization (for example, e-health and primary care) and to determine the attractiveness of these options compared with existing health care models (for example, clinic- or hospital-based models).

Results

A two-class model yielded the lowest BIC (

32). The utility coefficients in

Table 1 denote preferences. Participants in both classes thought that people would contact an EIS that has no wait times, incorporates direct contact with mental health professionals, allows people to talk to a service provider from their own culture, and involves an assessment that takes one hour. Moreover, participants in both classes predicted that people would contact a service that provides information regarding psychological treatment and has been endorsed by those who have experienced mental health problems.

Results for the first class (N

=241, 43% of the sample), which we termed the conventional

-service class, suggested that people with mental health issues would be more likely to contact an EIS located at a clinic or hospital and staffed by psychiatrists or psychologists. Participants in this class also recommended that the service be available to anyone age 18 or older, advertise at weekly events, and offer appointment scheduling at convenient times for both the patient and the service. Importance scores showed that this class was sensitive to variations in the background of the service providers (favoring psychiatrists and psychologists), assessment format (favoring face-to-face contact), and the opinions of people who have experienced mental illness and who have deemed this service helpful (

Table 2).

Participants in the second class (N

=321, 57%), termed the convenient-service class, predicted that people would be more likely to contact a service that is open to walk-in and self-referral and accessed from respondents' homes. Participants in this class recommended that the service be available to anyone age 12 or older, staffed by mental health nurses, and advertised on radio and television. Importance scores showed that this class was sensitive to variations in wait times (favoring none), level of family involvement (preferring collaborative decisions), and the referral process (favoring self-referral) (

Table 2).

Demographic information about the participants and the classes is summarized in

Table 3. Parameter estimates for the covariates (U) reflect the strength of the relationship between the covariates and membership within each class. Membership in the conventional-service class was associated with being either a patient or a family member (U=.40, Z=5.42, p<.001) and male (U=.23, Z=3.43, p<.001). Membership in the convenient-service class was associated with being a mental health professional and female.

Individual utility coefficients were used to create simulation models (

24). Three EIS options were created for these simulations. The e-health option involved Internet advertising and service contacts at an Internet site where professionals answer questions about mental illness. This service would be used from home and involve self-referral, no appointments, and individual decisions about whether to provide self-identifying information. Primary care involved service at a family doctor's office, self-referral, and appointment scheduling convenient for both parties. The clinic-hospital option involved service at a clinic or hospital, referral by a family doctor or mental health professional, and appointments made on the basis of convenience to the service.

Among the 321 participants in the convenient-service class, 96% (N

=308) thought that people would utilize the e-health option. The conventional-service class was split, with 44% (N=107) predicting that people would use primary care, and 42% (N

=102) predicting that people would use the clinic-hospital. The remaining 13% of the conventional-service class (N=32) predicted that people would use the e-health option. Overall, 61% of the entire sample thought people would use an e-health option (

Table 4).

Discussion

A DCE was used to determine attributes of an EIS that individuals with emerging symptoms of mental illness would be most likely to contact. These methods have been borrowed from marketing research and health economics (

35) and are relatively new to mental health care (

12). This study demonstrated the ease of administering DCEs in a mental health setting. The input from patients, family members, and professionals provided a comprehensive view of service structure and delivery preferences (

17). As expected, the analyses allowed us to determine the proportion of each respondent group within discrete latent classes. The covariate analyses enabled us to determine the independent contributions of demographic factors to class membership.

Two classes of respondents were identified. Respondents in the conventional-service class thought that people would be more likely to contact EISs that included mutually convenient appointments at a clinic or hospital. They were sensitive to variations in professional background. Those in the convenient-service class endorsed the view that people with mental illness would be apt to contact EISs that emphasize ease of access (for example, self-referral to a service that a person could use at home). Neither class prioritized receiving information about medication, consistent with previous research (

37).

Wait times exerted a greater influence on the choices of the convenient-service class (most professionals were members of this class) than on those of the conventional-service class (most patients and family members were members of this class). A strong relationship between wait times and the likelihood of failing to attend one’s initial appointment has been previously described (

38). In one study, each day of delay during the first week after contact had a significant impact on the rate of kept appointments (

38), suggesting that those who obtain appointments for psychiatric care with short wait times are more likely to attend initial appointments (

38,

39).

Participants in both classes predicted that people would contact services with minimal wait times, increased patient autonomy, information regarding psychological treatment, and endorsements by other service users. The similarities between the two latent classes reinforce key EIS aspects that are strongly preferred. Incorporating the most important and universally preferred attributes would increase the likelihood of EIS use.

An important aspect of this study’s methodology was the RFC simulations. These predicted that providing only one type of EIS would not sufficiently meet the needs of the entire range of potential clients, even though the similarities in preferences between the two latent classes might suggest that approach. For example, the simulations predicted that 96% (N

=308) of the respondents in the convenient-service class would most likely use an e-health option, compared with only 13% (N

=32) of the conventional-service class. The differences in the classes here suggest that some participants may have been more inclined to use a primary care or clinic-hospital model, whereas the majority of one class saw the benefit of adopting an e-health option, consistent with previous research (

21). Depending on the desired target population of an EIS, service design may need to incorporate different attributes to increase the range of choices available.

In addition to highlighting the need to provide a range of options for service users, the results also underscore the need to incorporate multiple perspectives in service design. Despite areas of agreement between respondent groups, many professionals were inaccurate in their prediction of the EIS design preferences of patients and family members, consistent with previous research (

17). Both classes had high utility scores for service attributes that underscored autonomy, suggesting that people experiencing psychiatric symptoms may prefer a collaborative health care model in which they have input regarding which services will best suit their individual needs (

10). Future EISs designed with a variety of perspectives in mind would provide service users with a range of choices.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. The survey was designed to determine what a broad sample of patients, family members, and professionals thought people with mental illness would prefer in an EIS. For the purposes of this survey, the number of family members was insufficient to obtain stable preference estimates. Thus we were unable to analyze patients and family members separately. The survey asked participants to respond from the perspective of someone accessing an EIS for the first time. Many participants were already involved in traditional service models. As a result, they may have been more favorably disposed to the existing model. Those who rejected existing services would not have been included in our sample. The inclusion of respondents across a broad age range might be considered a limitation. However, experienced service users have a knowledgeable perspective and are considered valuable informants (

37). Furthermore, covariate analyses indicated that once a participant’s status (that is, patient, family member, or professional) and gender were accounted for, age did not predict class membership.

The sample was also limited in its cultural diversity—94 participants (17%) were immigrants. Participants born in another country were more likely to be members of the conventional-service class. According to 2006 census data, Hamilton had the third highest foreign-born population (24.4%) in Canada, higher than the national level of 19.8% (

40). Therefore, it appears that the sample somewhat underrepresented the diversity expected from the study’s local environment. This may reflect a “healthy immigrant effect” (

41) or underutilization of mental health services by this population. Similarly, family members recruited from family support groups and clinic waiting rooms are likely to represent only a subset of the entire population of family members of persons with mental illness (for example, they may have been more actively involved in their relative’s care than those who did not attend appointments or support groups).

Future studies should address the aforementioned limitations. For instance, DCE studies could focus on recruiting a larger number of family members in order to be able to analyze the three groups separately to determine whether preferences differ significantly from the results obtained here. In addition, studies should assess the preferences of individuals who are experiencing mental health symptoms but who are not yet involved in treatment services and considering using EISs for the first time. It would also be valuable for future research to determine whether preferences for mental health EISs vary as a function of cultural background or specific psychiatric diagnoses. Finally, attributes that influence whether people access a mental health service may not be the same as those that influence whether they remain in a treatment program. This question is the focus of a second study.

Conclusions

The results of this study underscore the importance of incorporating key attributes in designing an EIS to maximize use by people with emerging mental illnesses. First, EISs should minimize wait times. Second, given that the two classes in this study reported both similar and divergent preferences, there should be a focus on providing a range of service options. This may include e-health, community-based primary care models, and more traditional hospital-based approaches to EISs. This approach will enhance uptake and adherence by targeting a wider range of people and maximizing choice and patient autonomy. Finally, this study highlights the need for future EISs to adopt a collaborative approach that involves patients and family members in decision making.