Persons of low socioeconomic status, members of racial-ethnic minority groups, and persons with mental illness have been shown to have increased risk of housing instability (

1,

2). Housing instability is a complex construct featuring a continuum of severity—ranging from homelessness to residential transience (frequent moves) and financial stress in maintaining stable housing (

1,

3). This instability affects numerous aspects of health and well-being and has been linked to adverse outcomes, such as poor health and difficulty in accessing health care (

4,

5). In addition, persons with mental illness who experience housing instability are more likely to come into contact with police and more likely to be charged with criminal offenses (

6).

Although these phenomena are well documented, the majority of studies that have examined mental illness and housing instability have focused on homelessness or defined housing instability as a unified construct that encompasses transience and financial stress (

1). Little research has specifically examined residential transience and its association with mental illness, despite evidence that moving frequently can disrupt social and institutional attachments and lead to mental distress (

3,

7,

8). Davey-Rothwell and others (

8) found that adults who had moved two or more times in the past six months had higher rates of depression compared with those who moved less frequently. Qin and colleagues (

7) noted that the more frequently a child moved in his or her lifetime, the higher the child’s risk of suicide.

This study furthered this research by evaluating the association between residential transience and mental illness in a nationally representative survey of U.S. noninstitutionalized adults. In addition, the study examined whether the association between mental illness and residential transience varied by race-ethnicity, given the documented differences in residential transience among racial and ethnic minority groups (

3). Understanding these associations may be important for mental health treatment planning and could guide future research efforts. Determining whether associations between residential transience and mental illness differ by race-ethnicity may also assist in targeting intervention and treatment activities and may be important for programs addressing housing instability.

Methods

Data were from the 2008–2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) public use files, archived by the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (

9). NSDUH is an annual cross-sectional survey of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population ages 12 and older. NSDUH data are collected by using a complex survey design to provide nationally representative estimates of persons residing in households and noninstitutional group quarters—such as shelters, rooming houses, and dormitories—and civilians residing on military bases. These analyses utilized data for approximately 154,400 adults from the NSDUH (an annual average of 38,600 adults from 2008 through 2011). Secondary data analyses of the deidentified NSDUH public use files have been certified as exempt research by the RTI International Institutional Review Board.

Classification of mental illness in NSDUH is based on a predictive statistical model calibrated in a substudy that used telephone-based clinical interviews of a subset of adult NSDUH respondents. In the calibration study, adults were classified as having mental illness if they had a

DSM-IV diagnosis, excluding substance use disorders and developmental disorders, in the past 12 months (

10). A statistical model was developed that predicted the presence of mental illness on the basis of participants’ responses to scales assessing psychological distress (Kessler 6;

11) and functional impairment (an abridged version of the World Health Organization Disability Schedule [WHODAS];

12). This model was then applied to the adults in the full NSDUH sample. In 2008, only half of the participants were administered the WHODAS. Therefore, in 2008, these analyses were restricted to the half-sample of participants who received the WHODAS. The full sample was used for all subsequent years. More information can be found in

Results From the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (

13).

Residential transience does not have a consistent definition across studies. Davey-Rothwell and colleagues (

8) used a cut point of two or more moves in the past six months, and Qin and colleagues (

7) examined number of moves across the life span. However, NSDUH assesses number of moves in the past year. Therefore, the population distribution of moves in the past year was used to determine a cut point of three or more moves in the past year.

Race-ethnicity is assessed in NSDUH by using seven categories: non-Hispanic white, black, Native American/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Asian, and two or more races; and Hispanic. Because of sample size restrictions, non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander adults were excluded from these analyses. The final sample comprised 63.5% non-Hispanic white adults, 12.4% non-Hispanic black adults, 1.5% non-Hispanic Native American/Alaska Native adults, 3.8% non-Hispanic Asian adults, 3.2% non-Hispanic adults reporting multiple races, and 15.6% Hispanic adults. Additional covariates included sex, age, marital status, insurance status, employment, poverty, metropolitan area, and DSM-IV diagnoses of alcohol and illicit substance use disorders.

All analyses were conducted by accounting for the complex survey design. Weighted annual average prevalence estimates were generated for residential transience by mental illness status and race-ethnicity. The analyses used t tests to test differences in the prevalence of residential transience by racial-ethnic group and mental illness status. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between mental illness and residential transience and test for an interaction between mental illness and race-ethnicity on residential transience. All tests were two-tailed, with p<.05.

Results

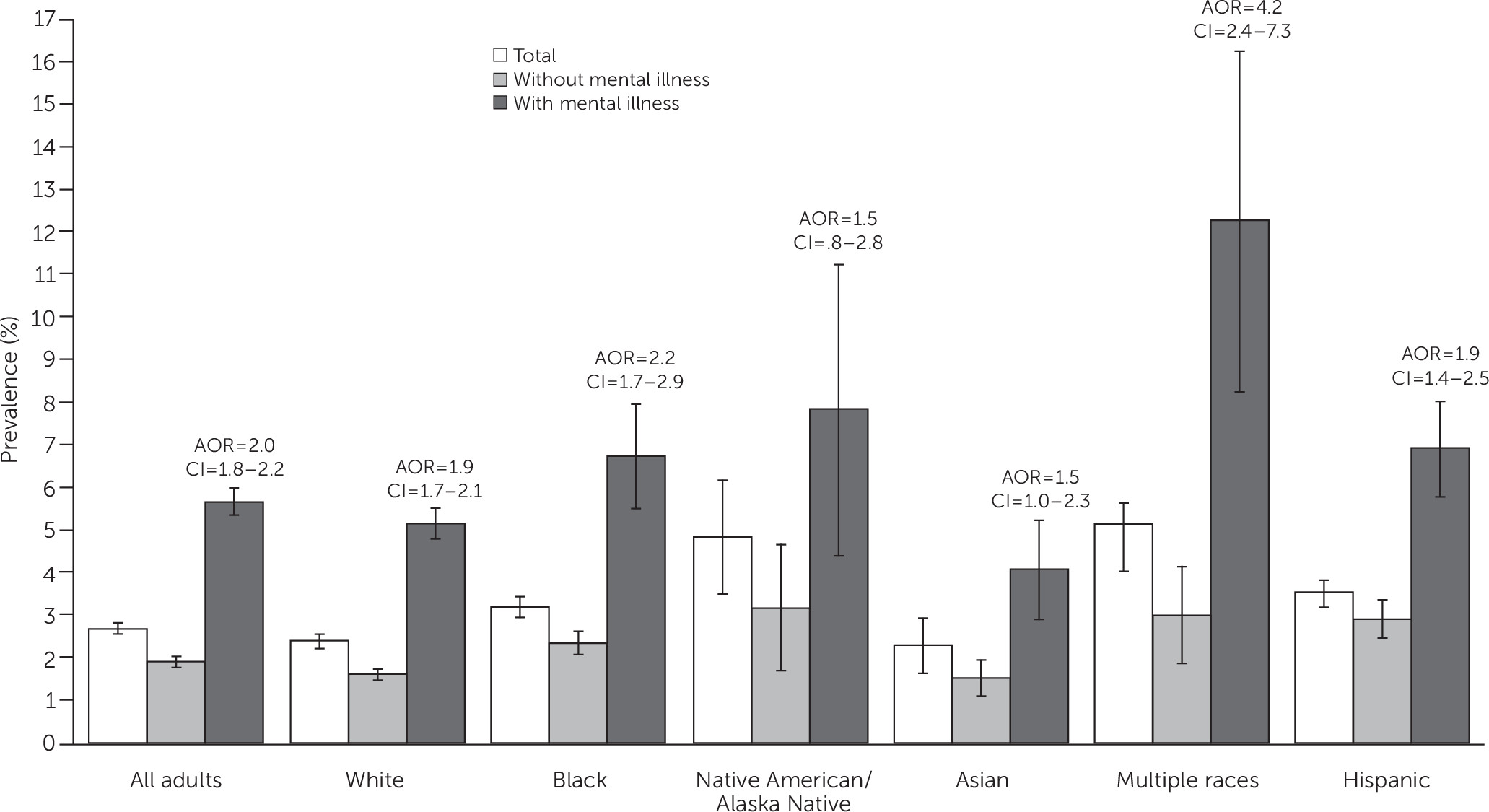

Approximately 2.7% of U.S. adults reported residential transience in the past year (

Figure 1). Residential transience was higher among adults with mental illness than without mental illness (5.7% versus 1.9%, p<.001, excluding Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders). This pattern was consistent across all racial-ethnic groups. Residential transience also differed by race-ethnicity. Adults reporting multiple races had the highest prevalence of residential transience (5.1%), whereas Asian adults (2.3%) had the lowest prevalence of residential transience. Non-Hispanic whites (2.4%) had lower rates of residential transience than blacks (3.2%), Hispanics (3.5%), Native American/Alaska Natives (4.8%), and adults reporting multiple races (5.1%).

Similar results were found when residential transience was stratified by mental illness status and race-ethnicity. A total of 12.3% of adults who reported multiple races and mental illness experienced residential transience, approximately double the rate among whites (5.1%), blacks (6.7%), Asians (4.1%), and Hispanics (6.9%).

Among all adults, the odds of residential transience were twice as high among adults with mental illness compared with adults without mental illness, after adjustment for sex, age, marital status, employment, federal poverty level, metropolitan area, and alcohol and drug use disorders (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.99, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.81–2.19;

Figure 1). Evaluation of the interaction of race-ethnicity and mental illness indicated that the association between mental illness and residential transience varied by race-ethnicity (Wald χ

2=164.52, df=11, p<.001) even after adjustment for confounders. In models stratified by race-ethnicity, the odds of residential transience were significantly higher among persons with mental illness versus no mental illness for whites (AOR=1.91, CI=1.73–2.10), blacks (AOR=2.18, CI=1.65–2.88), and Hispanics (AOR=1.89, CI=1.42–2.52). There was no significant association between mental illness and residential transience among Native American/Alaska Natives and Asians, once additional covariates were included. The magnitude of the association of transience and mental illness was greatest for adults reporting multiple races; those with mental illness had a fourfold increase in residential transience compared with those without mental illness (AOR=4.15, CI=2.36–7.30).

Discussion

The presence of past-year mental illness was significantly associated with past-year residential transience, independent of other factors, including poverty, age, and the presence of co-occurring substance use disorders. This association was significant for adults of all racial-ethnic groups, with the exception of Native American/Alaska Native and Asian adults, possibly as a result of small sample sizes. Most notably, the association between mental illness and residential transience differed in magnitude across the various racial-ethnic groups. Adults of multiple races with mental illness had particularly high odds of residential transience compared with their counterparts without mental illness.

Because this is the first known study to examine the association between residential transience and mental illness by race-ethnicity, our findings should be considered preliminary until replicated. However, if the findings are replicated, future research might consider whether multiracial adults with mental illness experience particular discrimination or other challenges in maintaining stable housing compared with adults with mental illness in other minority groups.

Identifying racial-ethnic differences in the association between residential transience and mental illness is also important because of the potential consequences of residential transience. Housing instability, overall, has been linked to difficulty obtaining general medical and mental health care (

4,

5), and residential transience may also act as a barrier to health care service use by disrupting social and institutional networks. Given that racial-ethnic differences in mental health service use have been widely documented (

14), variations in the prevalence of residential transience may play a role in the differential rates of service use. Lack of service use, in turn, may result in higher functional impairment, possibly making transience more likely (

1). Future research examining whether residential transience acts as a barrier to care—for example, through difficulty accessing treatment from a new location or inability to continue services with a trusted clinician—may be important for efforts to reduce racial-ethnic disparities in service use and to improve access to care for all adults with mental illness.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations, which also point toward future research. First, the cross-sectional design of NSDUH prevents the examination of temporal patterns and causal mechanisms. Symptoms of mental illness may cause difficulty maintaining a stable residence. Alternately, frequent relocation may introduce a significant life stress that contributes to the development of mental illness among vulnerable individuals (

8). The relationship between mental illness and residential transience is likely reciprocal, which would suggest a damaging cycle of mental illness and residential transience, each contributing to the other. Implementing screening programs may assist clinicians in identifying patients in need of additional services and possibly interrupt this cycle. Instruments that have been developed for screening for housing instability—for example, in the Veterans Health Administration and other health care settings (

15)—may prove useful in generalized settings.

Notably, mental illness is determined in NSDUH by using a predictive algorithm and not by a clinical interview. Future research would benefit by evaluating the relationship of specific disorders (and disorder severity) to residential transience. In addition, this study used broad categories for racial-ethnic groups; the use of more refined categories was precluded by small sample sizes of Native American/Alaska Native adults and adults reporting multiple races, in particular. More targeted studies may be needed to evaluate transience and mental illness in specific racial-ethnic groups, such as various Hispanic groups.

Conclusions

Although preliminary, these findings indicate that mental illness is associated with residential transience and that race-ethnicity may play an important role in this association. Additional studies are needed to directly explore the influence of racial-ethnic biases, discrimination, and disparities at multiple levels—for example, housing policy and housing support programs—as well as to consider how these complexities affect access to mental health care for recovery.