The Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended the coverage requirements of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) to many, but not all, Medicaid beneficiaries, including three million disabled adults enrolled in fee-for-service care (

1–

3). Consequently, state Medicaid policy makers retain considerable discretion in the design of coverage for mental health and substance use disorder treatment for this highly vulnerable population. This column brings to light a corrigible mismatch between a population’s health needs and the current statutory protections for mental health and substance use disorder treatment. It concludes with a description of three strategies that states may deploy to extend the MHPAEA’s provisions to Medicaid coverage for adult beneficiaries with disabilities.

The MHPAEA and the ACA

The proposition that a Medicaid population may have something to gain from the MHPAEA may at first appear to be a red herring, given the historically generous coverage for mental health and substance use disorder services under Medicaid compared with commercial insurance. However, a more relevant comparison is the scope of available coverage relative to a population’s health needs. Whereas the annual prevalence of serious mental illness among privately insured adults is less than 5% (

4), approximately 33% of working-age Medicaid beneficiaries who qualify for the program on the basis of a disability have a serious mental illness (

5).

The application of the MHPAEA requirements to the Medicaid program has occurred in two main phases. Before passage of the ACA, the initial influence of the MHPAEA on state Medicaid programs operated through Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) and affected all adult Medicaid MCO enrollees (

6). Specifically, Medicaid MCOs were required to comply with the MHPAEA for features of insurance coverage that they determine (for example, out-of-network coverage, utilization management, and services in excess of state contract specifications) (

7). That requirement still stands.

The ACA then extended the authority of the MHPAEA to additional Medicaid beneficiaries by enhancing the coverage requirements of Medicaid’s Alternative Benefit Plans (ABPs) (

8). For roughly a decade, states have had the flexibility to offer these alternative packages to meet the needs of some Medicaid eligibility groups (

8). The ACA stipulated that ABPs must now cover mental health and substance use disorder services that satisfy the MHPAEA requirements and must conform to the MHPAEA in the management and delivery of those services (

8–

10). These requirements hold for both fee-for-service and managed care ABPs (

7). Although few states implemented ABPs before 2014 (

11), these plans are the source of coverage for adults who become eligible for Medicaid through the ACA’s optional Medicaid expansion. States must enroll these beneficiaries into ABPs. To date, 28 states have chosen to expand their Medicaid programs under the ACA (

12).

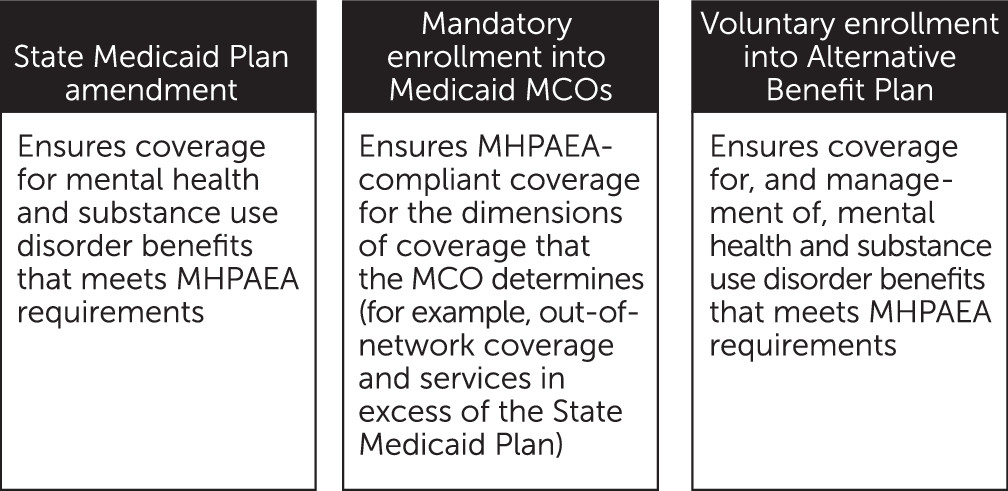

Three Strategies for Providing Coverage

Despite these historic regulatory changes, the provision of parity-consistent coverage for adult beneficiaries with disabilities is not ensured. This beneficiary group is predominantly enrolled in fee-for-service programs rather than Medicaid MCOs (

3). In contrast to the new ABPs, traditional Medicaid fee-for-service coverage is not subject to the MHPAEA (

6); and adult beneficiaries with disabilities are exempted from mandatory enrollment into ABPs (

13). Each of these reasons for the limited reach of the MHPAEA to beneficiaries with disabilities contains within it a potential remedy that states may pursue: first, provision of parity in traditional fee-for-service coverage; second, mandatory enrollment into Medicaid MCOs; and third, voluntary enrollment into ABPs (

Figure 1).

States may ensure that fee-for-service coverage is consistent with the MHPAEA by including such coverage in the State Medicaid Plan, in which each state specifies the benefits and operations of its Medicaid program. The bundle of services described in the plan constitutes the totality of services that the program provides to fee-for-service beneficiaries and the minimum covered services that comprehensive MCOs must deliver (

14). Because State Medicaid Plans are not subject to the MHPAEA (

7), state action may be required to bring benefits into alignment with federal parity regulations.

It is difficult to say whether, or to what extent, current Medicaid coverage of mental health and substance use disorder services outlined in State Medicaid Plans adequately meets the needs of beneficiaries with disabilities. A summary of the benefits contained in these plans indicates that annual limits on mental health or general medical visits are present in at least ten states (

15). These annual limits range from four to 40 psychotherapy visits. In some states, the visit caps apply equally to general medical and mental health visits, whereas this does not appear to be the case in other states. Whether these visit limits impede receipt of needed treatment is unknown. However, on the face of it they appear inconsistent with the spirit, if not the letter, of the MHPAEA. Because states routinely amend the State Medicaid Plan, this strategy seems at least administratively feasible.

Many states plan to scale back their fee-for-service programs by expanding mandatory enrollment into Medicaid MCOs for adult beneficiaries with disabilities (

3). In so doing, these states will automatically extend some of the MHPAEA’s provisions to this population. However, to ensure that all provisions of the MHPAEA pertain to Medicaid MCO enrollees, the state would still need to include covered services that are parity compliant in the State Medicaid Plan (

7,

16). As noted above, Medicaid MCOs must generally comply with the federal parity law for the features of insurance coverage that they determine. However, with respect to covered services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services does not consider a Medicaid MCO to be out of compliance with the MHPAEA if the provided services reflect those in the State Medicaid Plan (

7).

Finally, states may encourage adults with disabilities to enroll in ABPs. The current exemption from mandatory enrollment for this group stems from past concerns about the potential inadequacy of benefits under ABPs for adults with disabilities. However, because these plans must now include a broad set of benefits, they present a coverage option for mental health and substance use disorder services that may be as good as, or better than, traditional fee-for-service programs. Outreach to beneficiaries with disabilities about these coverage options may be necessary because they represent a substantial departure from the pre-ACA status quo (

16).