Many older black adults are at risk of depression because of social stressors, including poverty, low education attainment, exposure to violence, and discrimination (

1), as well as health problems, including high rates of obesity, substance use disorders (

2), and dementia (

3). Compared with older white adults, older black adults tend to endorse a greater number of depressive symptoms (

4). However, black adults often have limited access to and underutilize mental health services (

5–

8). The underutilization may be partly explained by stigma surrounding mental illness, mistrust of mental health care practitioners, and a preference for nonpharmacological treatment strategies (

9,

10). As a result, depression is often underdiagnosed and undertreated among black individuals with depression (

1,

11). One barrier to reducing these disparities is lack of evidence about interventions and outcomes (such as remission rates among individuals taking antidepressants), particularly in diverse aging populations.

Studies evaluating outcomes of antidepressant treatment among middle-aged black adults have yielded mixed results. Some studies suggest that black adults have worse antidepressant treatment outcomes compared with white adults (

12–

14). A number of studies that used older antidepressants have shown that black adults responded more quickly than white adults (

15,

16). Other studies have shown similar remission rates for black and white participants (

17–

19), including studies adjusting for baseline clinical and sociodemographic variables (

19–

21. Likewise, pooled analyses from pharmacy-sponsored databases have shown similar remission rates between adults from racial-ethnic minority groups and white adults (

22,

23).

Studies comparing antidepressant outcomes have focused on middle-aged adults. Few such studies have focused on adults in later life. Investigating remission during antidepressant treatment among aging minority populations is important because both older age (

24,

25) and race-ethnicity may alter antidepressant remission rates. Studies investigating treatment outcomes among older black adults have been conducted in the context of collaborative care models of depression treatment. One such study showed that older black adults responded to treatment at rates similar to rates among older white adults (

26), whereas another showed less benefit for older black adults compared with older white adults (

27). To our knowledge, no studies have looked at differences in remission rates among older black and white adults who were taking antidepressants alone.

Using data from a multisite trial sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), this study explored whether older black and white participants with major depressive disorder differed in rates of attrition and remission during open-label treatment with venlafaxine and supportive care. We also explored differences between the two groups in clinical features, rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidity (including cognitive function and obesity), receipt of psychotherapy from nonstudy providers, and adequacy of prior trials of antidepressants.

Methods

Description of the Primary Study

Data originated in an NIMH-sponsored multicenter trial (Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Toronto) entitled “Incomplete Response in Late-Life Depression: Getting to Remission” (IRL-GREY) (

28). In the initial phase of IRL-GREY, older adults with major depressive disorder were treated openly with venlafaxine extended-release for 12–14 weeks. Participants who did not respond to venlafaxine extended-release at a maximum daily dose of 300 mg were randomly assigned to venlafaxine extended-release plus aripiprazole or venlafaxine extended-release plus placebo. A very small percentage of participants were treated for up to 24 weeks for feasibility reasons (for example, transportation or travel difficulties) in order to achieve the maximum dose of venlafaxine and to determine definitively whether they qualified for the subsequent double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole. This study reported here examined data only from the open-treatment phase with venlafaxine extended-release.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be age 60 or older, have a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (single or recurrent episode), meet criteria for a current nonpsychotic major depressive episode as diagnosed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (

29), and have a Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score of ≥15 (

30). Exclusion criteria included presence of clinical dementia, history of a bipolar or a psychotic disorder, current psychotic symptoms, alcohol or drug abuse or dependence in the past three months, high suicide risk and refusal to be hospitalized, an unstable medical illness, inability to safely taper or discontinue psychotropic medications before study initiation, and a contraindication to venlafaxine extended-release or aripiprazole.

Participants

Between July 20, 2009, and December 30, 2013, we screened 1,098 depressed individuals age 60 and older; 490 were excluded because of failure to satisfy all eligibility criteria. Of the 608 eligible participants who consented to participate, 140 withdrew before starting treatment. The remaining 468 participants started treatment. We excluded from this analysis eight Asian/Pacific Islander participants and one Native American participant and included 47 black and 412 white participants (N=459). They were recruited on the basis of referrals from mental health facilities and clinics (N=161, 35%), advertisements (for example, radio, newspaper, and staff presentations) (N=118, 26%), research programs (N=81, 18%), primary care or nonpsychiatrist physicians (N=66, 14%), and other miscellaneous sources (N=33, 7%). No difference in referral sources were noted with respect to the proportion of black and white participants. The protocol was approved by the three local institutional review boards. All participants gave written informed consent.

Measures

We assessed depression severity with the MADRS (

30), a ten-item, clinician-administered rating scale (possible score range, 0–60; higher scores indicate greater severity). Depression remission was the outcome variable for this analysis. Remission was defined as a MADRS score of ≤10 for two consecutive assessments at the end of the open-label treatment phase. Depression severity was also assessed at baseline with the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) (

31) to allow comparison of our data with data from other trials. Suicidal ideation was assessed with the 21-item Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI) (

32); a score of ≥1 indicated current suicidal ideation.

Medical comorbidity and burden were assessed with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) (

33), which rates each organ system from 0, no problem, to 4, end organ failure or severe functional impairment (possible total score range, 0–52). Quality of life was measured with the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey from the Medical Outcomes Study (SF-36) (

34). The Antidepressant Treatment History Form (

35) was used to assess the adequacy of previous trials of antidepressants or electroconvulsive therapy on a scale of 0–5, with a score ≥3 representing an adequate trial.

We measured general anxiety symptoms with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-anxiety) (

36). The BSI-anxiety is a six-item, self-report questionnaire rated on a 5-point scale (0, not present; 4, extremely severe). Anxiety sensitivity (fear of symptoms of anxiety and panic) was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI) (

37). The ASI is a 16-item, self-report questionnaire rated on a 5-point scale (0, a little; 4, very much).

Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) (

38) was used to evaluate global cognitive functioning as well as delayed memory ability. Executive functioning was evaluated with the combined mean of two tests (Color-Word Interference and Trail Making) on the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function Scale (D-KEFS) (

39). All scores were age normed. Current or past anxiety disorders and drug or alcohol use were evaluated with the SCID.

Other pretreatment assessments focused on basic demographic information (age, sex, race, and education) and clinical variables (age at onset of first lifetime depressive episode, duration of current episode, current receipt of any psychotherapy outside the trial, history of substance abuse, and body mass index [BMI]).

Treatment Protocol

Venlafaxine extended-release was initiated at 37.5 mg per day and titrated (in 37.5-mg increments separated by at least three days) to a target dose of 150 mg per day. At the end of week 6, nonremitters had their dose increased further (in 37.5- to 75-mg increments separated by at least three days) to a target dose of up to 300 mg per day. The dose could be reduced at any time if participants experienced adverse effects. Lorazepam (up to 2 mg per day) could be prescribed for sleep or anxiety. Participants could also continue using some other medications for sleep (zolpidem, zopiclone, trazodone, and low-dose amitriptyline) or participate in outside psychotherapy if it had started prior to study entry and could not be discontinued.

Throughout the study, pharmacotherapy was embedded in a model of depression care management. The model included supportive clinical care focusing on psychoeducation about depression and its treatment, depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, countermeasures for medication adverse effects, and treatment adherence; the model did not incorporate any depression-specific psychotherapy (

40). Participants were seen once a week for the first two weeks and then every two weeks by study clinicians under the supervision of physician investigators. During each of these visits, the research team assessed depressive symptoms (MADRS), suicidal ideation (SSI), vital signs, and adverse effects (UKU side-effect rating scale [

41,

42]).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic characteristics of black and white participants were compared by using analysis of covariance for continuous variables or logistic regression for categorical variables. Analyses controlled for site differences after testing verified that there were no site-by-race interactions. For categorical variables, if rates were small, the exact logistic regression was used. Age-normed cognitive measures were analyzed, with the analysis controlling for site, education, sex, medical burden, and severity of depression. Kaplan-Meier curves (

43) were employed to display time to dropout and time to initial remission for the black and white participants classified as remitters at the end of treatment. Formal inference for differences in attrition and remission rates used Cox proportional hazards models that controlled for site (

44).

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 459 participants in the sample, 10% (N=47) were black and 90% (N=412) were white. The Toronto site had a lower proportion of black participants (seven of 120, 6%) than Pittsburgh (20 of 199, 10%) or St. Louis (20 of 140, 14%), but the differences were not significant. Participant characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The proportion of males was lower among black participants than white participants, and black participants had fewer years of formal education. The groups did not differ in age or in the proportion living at home alone (sole occupant of household).

Medical Comorbidity and Health-Related Quality of Life

Black participants had greater general medical comorbidity as evidenced by a greater number of affected organ systems on the CIRS-G. They also endorsed worse physical health–related quality of life, but they scored higher than the white participants on the mental health component of the SF-36. Black and white participants were comparable in terms of their mean BMI and the percentage of individuals who were obese (BMI ≥30). No differences were found in rates of diabetes; however, black participants had higher rates of hypertension.

Depression Severity and Psychiatric Comorbidity

Black and white participants had similar levels of depression severity at baseline as reflected by their HRSD-17 and MADRS scores (

Table 2). They did not differ in the mean age at onset of depression, percentage with recurrent episodes of depression, duration of the current depressive episode, percentage with suicidal ideation, prior suicide attempts, number of comorbid anxiety disorders, or self-reported anxiety symptoms (BSI). However, black participants self-reported a higher rate of anxiety sensitivity (ASI).

History of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

White participants were more likely than black participants to have received an adequate trial of antidepressants before enrolling in the study and to have received psychotherapy.

Cognitive Function

When the analysis controlled for age, site, years of education, sex, medical burden (CIRS-G total scores), and depression severity (HRSD-17), black participants had lower RBANS total score, lower delayed memory scores, and lower D-KEFS executive functioning scores.

Attrition

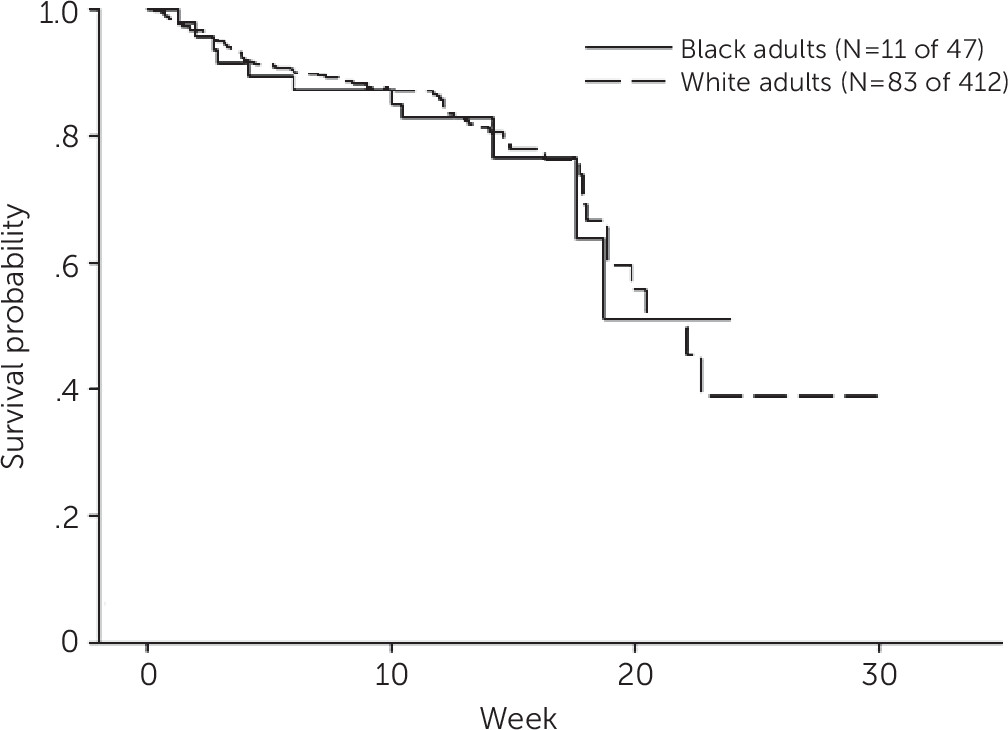

Over the course of treatment, 94 of the 459 participants (20%) withdrew from treatment: 11 of 47 (23%) black participants and 83 of 412 (20%) white participants. Participants withdrew because of adverse effects (N=31), preference for other treatment (N=26), noncompliance or nonadherence with study medication or appointments (N=11), supervening medical problems (N=10), or other reasons (N=16) (for example, relocation, cognitive impairment, worsening of depression, onset of psychosis, use of alcohol, use of drugs, or death). The Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows that black and white participants had similar time to and rates of dropout (

Figure 1).

Tolerability

The final daily dose of venlafaxine did not differ between the two groups. For black participants the mean±SD dose was 225.8±74.4 mg (median=225 mg). For white participants, the mean dose was 222.0±82.3 (median=225 mg). Black and white participants reported comparable side effects (

Table 3).

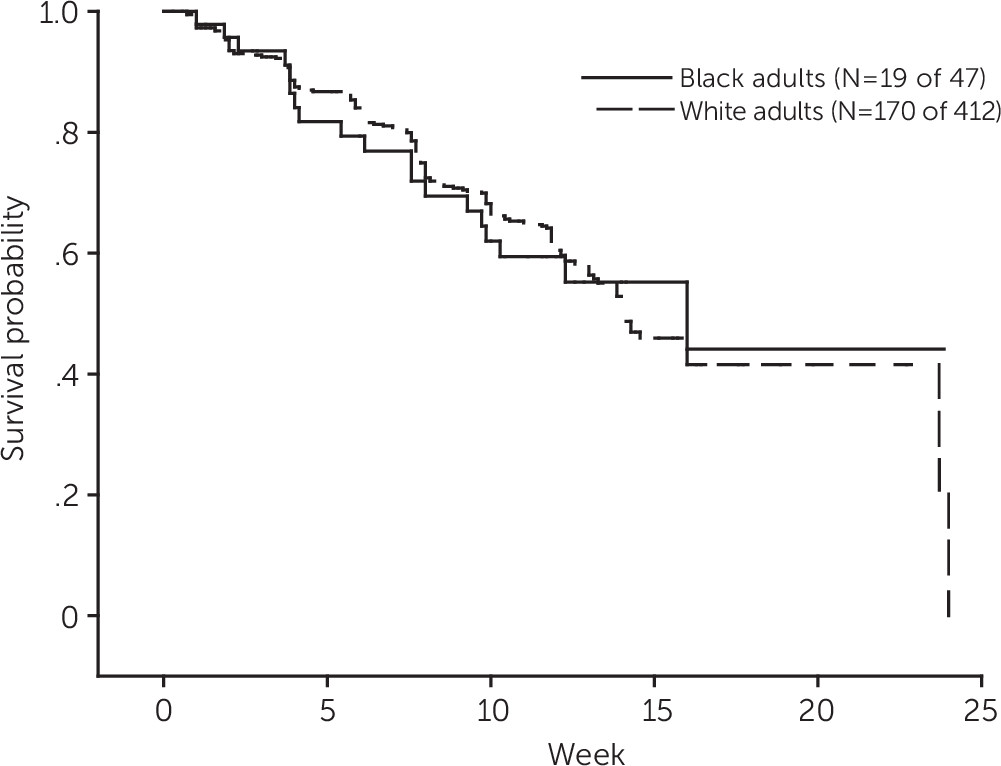

Remission

With open venlafaxine extended-release treatment and supportive care, 189 of the 459 (41%) participants reached depression remission—19 of 47 black participants (40%) and 170 of 412 white participants (41%). The Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows that black and white participants had similar time to and rates of remission (

Figure 2).

Discussion

This study investigated differences in major depressive disorder remission rates among older black and white adults who were using venlafaxine. Despite greater medical comorbidity, lower performance on cognitive tests, and less prior exposure to antidepressant treatment and psychotherapy, black participants were no more likely than white participants to discontinue antidepressant pharmacotherapy and experienced a rate of remission comparable to white participants. Because black participants had less education and worse cognitive performance, it might have been expected that they would have a lower rate of remission. In other studies, impairment in executive function, response inhibition (

45,

46), and verbal memory (

47) have been associated with worse antidepressant treatment outcomes in late-life depression.

Comparison to Previous Studies

It is difficult to compare the results of this analysis with results of other studies investigating antidepressant treatment outcomes among diverse racial groups because of the differences in recruitment strategies, study design, and interventions. Nevertheless, our results are similar to those of studies that showed little difference in treatment outcomes between middle-aged black and white adults (

17,

18,

27,

48), including results from pooled analyses (

23,

24). A number of studies have shown poorer outcomes among black participants, but when the analyses adjusted for baseline sociodemographic and clinical variables no difference was found (

13,

19–

22). Our analysis did not control for baseline differences. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that black participants may have responded better than white participants, as was seen in studies that used older antidepressants (

15,

16). Our results stand in contrast to results of studies showing worse outcomes for black participants. These differences may have resulted from use of different recruitment strategies and antidepressant classes and from the very different populations studied. For example, one study investigated HIV-positive individuals with depression (

12), and another study focused on the characteristics of participants whose depression worsened throughout the course of treatment (

14).

Most studies assessing outcomes among racial-ethnic minority groups have been of middle-aged populations. Very few have focused on older adults, and those are in the context of collaborative care models, which included antidepressants, psychotherapy, education, and case management. Our results are in agreement with those of one collaborative care study showing comparable rates of depression remission between white and black adults (

27), but they are in disagreement with results of another collaborative care study (

28). Although these other analyses are important, they provide us with little information about remission rates of persons taking only antidepressants. Focusing on this aspect of depression care is important because antidepressant monotherapy is often used as a first-line treatment for late-life depression.

Despite our findings and those of previous studies, the role of race-ethnicity in antidepressant treatment outcomes, especially among older adults, remains unclear. However, the bulk of this work suggests that treatment outcomes of black and white adults are similar. Additional research in this area is warranted to facilitate appropriate care for an aging and increasingly diverse population, as noted by the Surgeon General’s report (

1). Our analysis represents one of only a few studies exploring treatment outcomes among older adults from racial minority groups. To our knowledge, it is the only analysis to investigate remission via antidepressants alone among older black adults.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study included a large total sample, the use of structured interviews and validated measures to assess outcomes, a supportive clinical environment, and relatively low attrition rates. As shown in the tables, we had the power to detect clinically meaningful effect sizes. Limitations included an analysis of open-label treatment data from a trial that was not designed to specifically assess racial-ethnic differences in antidepressant response. We also cannot rule out the possibility that white participants were more treatment resistant than black participants, as evidenced by a history of a greater number of previous adequate trials of antidepressants and psychotherapy. Thus it is plausible that most of our black participants had been undertreated at the point when they enrolled in this study (

1). Participants self-reported their racial-ethnic backgrounds. Grouping participants into categories of race is problematic because such groupings do not imply sociocultural or genetic homogeneity. Differences in antidepressant treatment outcomes among racial-ethnic groups may be due to pharmacokinetic factors, such as differing polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 enzymes, which may lower enzymatic activity in certain ethnic groups (

49). We also cannot be certain whether the baseline differences between racial groups represented an accurate picture of help-seeking older adults in the general population or whether these differences were related only to the participating sites. In addition, many older black adults do not seek mental health services for their depressive symptoms, and when they do, depression is underdiagnosed. Therefore, our study sample may not reflect community-dwelling black older adults with major depressive disorder. There is a need for additional studies of more broadly representative samples recruited by systematic screening, as we have noted in a recent report on depression prevention among older black and white adults (

50).

We acknowledge that treatment outcome differences are not limited to the effects of race, although some variability may be accounted for by genetically mediated pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics differences. Differences may result from a myriad of sociocultural and socioeconomic barriers to effective antidepressant treatment, including poverty, violence, low education attainment, limited access to mental health services, and discrimination. In this context, we recognize that our black participants were recruited by traditional means, which often fail to result in a true representation of the older black population. Thus our study was limited to help-seeking seniors. Although studying this group is clinically meaningful, the results fall short of true generalizability. Finally, given that the majority of participants in both groups did not achieve remission, future studies should compare outcomes of second-line antidepressant treatment among black and white older adults.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that with adequate treatment it is possible to mitigate the disparity in antidepressant outcomes between older black and white adults. With appropriate pharmacotherapy embedded in good supportive care, black and white older adults with major depressive disorder can do equally well. However, such positive outcomes are not often seen because of the numerous barriers to recruitment (

51), retention (

52), and adherence (

19) that confront black individuals and others living under adverse socioeconomic conditions.