This study was a survey of 52 psychiatrists working in integrated care programs in diverse practice settings around the country. The study aimed to describe the work of these psychiatrists, including practice characteristics, team composition, common consultation questions, and systems issues, as well as consulting psychiatrists’ opinions and experiences working in this model of treatment.

Results

The mean age of the 52 psychiatrists responding to the survey was 51.9 years; 33 (64%) were men, and 19 (37%) were women. On average, respondents had been out of residency training for 18 years. Of all respondents, 11 (21%) had completed specialty training in addition to psychiatry training: four (8%) in family practice, two (4%) in internal medicine, one (2%) in pediatrics, and four (8%) in another specialty area. About half (N=24, 46%) had completed a fellowship: seven (14%) in child and adolescent psychiatry, three (6%) in primary care psychiatry or psychosomatic medicine, one (2%) in geriatric psychiatry, and 15 (29%) in another area.

Most survey respondents worked part-time in integrated care in a variety of settings, with the most common settings being federally qualified health centers or community health centers (N=22, 42%), academic medical center–affiliated primary care clinics (N=18, 35%), community mental health centers with a primary care clinic on site (N=17, 33%), and other primary care settings (N=13, 25%). Only 11 psychiatrists (21%) reported working full-time in a single setting.

Respondents also reported working in a variety of integrated care models, including 41 (79%) in a collaboration team (consultation to a primary care clinic and regular interaction with PCPs or behavior health professionals), 39 (75%) in administration, 38 (73%) in traditional referral or consultation (direct patient care consultations in psychiatric practice), 28 (54%) in colocated services (direct patient care consultations in a primary care clinic), 24 (46%) in caseload-based collaboration (regular reviews and consultations for a defined caseload of patients in a primary care setting and regular interaction with PCPs or behavior health professionals), 12 (23%) in reverse integration (collaboration with a primary care service or provider located in a mental health specialty setting), and 12 (23%) in other integrated care models. Psychiatrists reported that their compensation was provided by salary (N=35, 67%), fee for service (N=11, 21%), or other sources (N=15, 29%). Salaries were supported by a range of sources, including contracts to health plans (N=16, 44%), grant funding (N=13, 36%), and other sources (N=15, 42%).

Of the 52 psychiatrists surveyed, 47 (90%) reported working with at least one behavioral health professional. Few psychiatrists worked with only one behavior health professional (N=4, 8%), most worked with two to ten (N=36, 69%), and a few worked with 11 to 20 (N=4, 8%) or more than 20 (N=7, 13%). The survey respondents worked with a greater number of PCPs than behavior health professionals. Few worked with only one PCP (N=2, 4%), and most worked with two to ten (N=19, 37%) or 11 to 20 (N=19, 37%). Some worked with more than 20 PCPs (N=12, 23%).

Psychiatrists reported that they communicated with behavior health professionals in person (N=37, 71%) at least once per week (N=38, 73%) at scheduled times, with additional communication “as needed” (N=27, 52%). Psychiatrists reported that they communicated with PCPs in person (N=44, 85%) at least once per week (N=38, 73%) at scheduled times, with additional communication “as needed” (N=30, 58%).

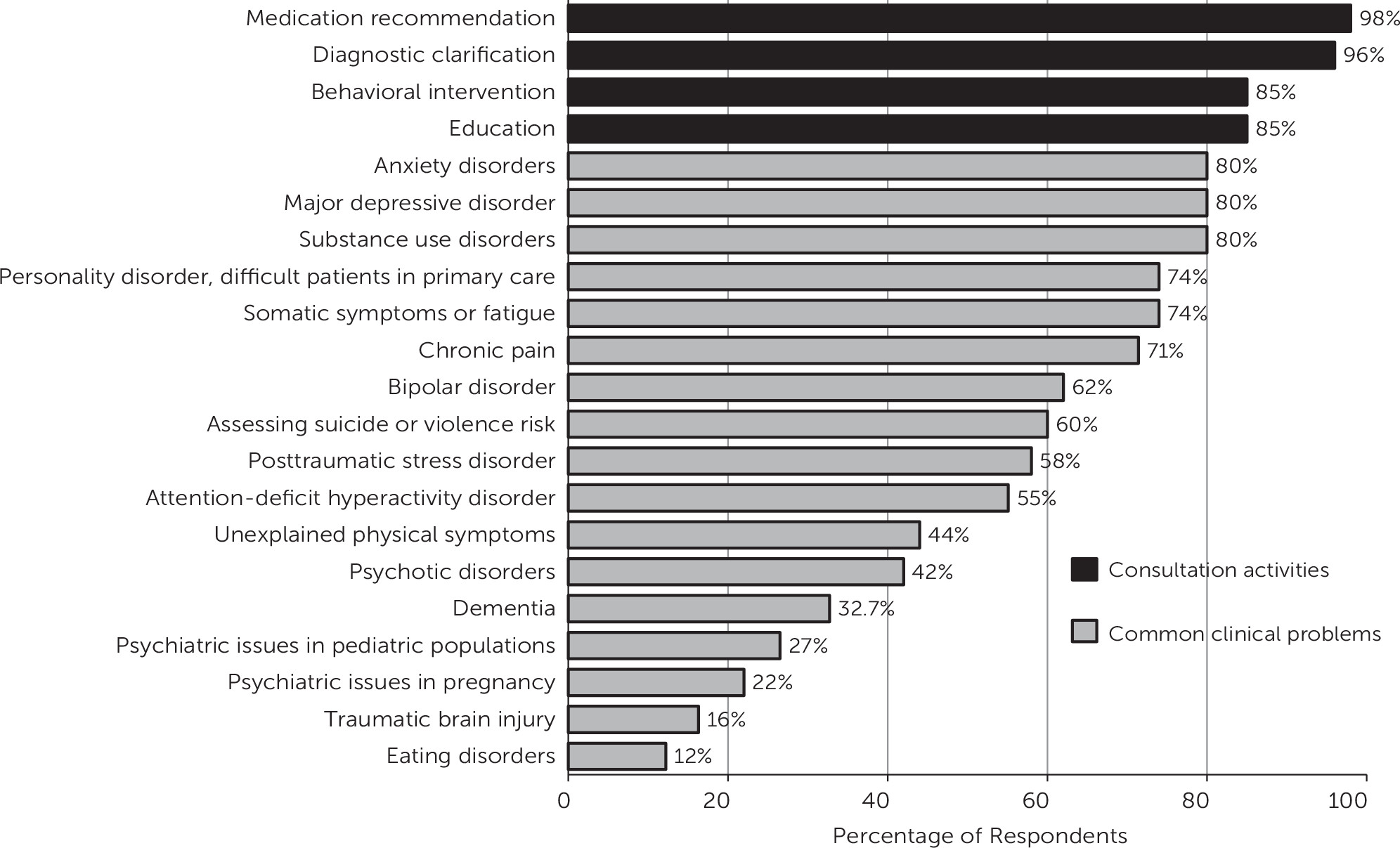

As shown in

Figure 1, nearly all respondents reported that they provided consultation regarding medication recommendations (N=51) and diagnostic clarification (N=50). Most respondents reported requests for consultation on behavioral interventions (N=44), and requests for education on a specific topic (N=44) were common. Psychiatrists also reported that the most common diagnoses associated with consultation were anxiety (N=40), depression (N=40), and substance use disorders (N=40).

The most common treatment strategy reported was evidence-based medication recommendations (N=42, 88%). Respondents also reported treatment strategies such as managing and treating general medical comorbidities (N=37, 76%) and monitoring modifiable risk factors (N=37, 76%).

The most common systems issues reported were directly related to working in a care team. These included communicating recommendations effectively to PCPs (N=36, 75%), working in integrated care teams (N=35, 73%), working with PCPs (N=34, 72%) and behavioral health professionals (N=34, 71%), and working with the group dynamics of an integrated care team (N=35, 73%).

Psychiatrists’ opinions of and experiences working in integrated care were overwhelmingly positive. Analysis highlighted four themes in respondents’ subjective experiences: working in a patient-centered care model, working with a team, the psychiatrist’s role as educator, and opportunities for growth and innovation.

Comments suggest that a strength of this model is that it fosters patient-centered care. One respondent noted that integrated care identifies “patients with mental health issues that without an integrated care approach would go undetected and untreated.” Comments also suggested benefits of working in a team—for example, “mutual support and efforts when helping patients who have a complex clinical presentation.” Many comments revealed positive effects of the education provided by psychiatrists. One psychiatrist noted, “I enjoy educating and feeling like my efforts are reaching so many more people than they do in the traditional model of care.” Finally, comments suggested that working in integrated care provides unique opportunities for growth and innovation by providing “opportunity to apply public health, ability to apply [evidence-based medicine], a chance to improve access, [and the] ability to support clinicians learning mental health.”

Even though most comments were positive, some challenges are summarized here to provide a comprehensive synopsis of psychiatrists’ experiences. The most commonly reported challenge was cultural change. Psychiatrists noted this challenge when switching to a more integrated model: “team members . . . feel threatened by expanding their scope of practice or by allowing others to enter into an arena previously reserved just for them.” Cultural change also emerged as a challenge when training new team members: “You get this well-designed functioning team and then someone leaves and the new person is hesitant/resistant for a while until you get them in the groove.” Respondents also reported financial challenges, including “always fighting for resources and reimbursement systems that tend to encourage nonintegration.”

Analysis of psychiatrists’ comments also clarified advice and essential professional qualities for the psychiatrist considering work in integrated care, including, “friendly demeanor, availability, clear concise communication, [and] curiosity and tenacity in pursuit of understanding the patient and relieving their suffering.” [Tables in the online supplement present additional findings.]

Discussion

This report summarizes the practice experiences of 52 psychiatrists working in diverse integrated care models across the United States. It also summarizes the opinions and experiences of these psychiatrists, focusing on the strengths and challenges of this work and offers advice to others considering a career in integrated care. Overall, psychiatrists’ comments indicate that working in integrated care is a rewarding experience. The challenges reported, including cultural change and financial barriers, are consistent with previously acknowledged challenges of implementing integrated care (

8).

Most integrated care psychiatrists in our study were working in primary care settings in a collaboration team model of integrated care, working closely with a substantial number of PCPs supported by fewer behavior health professionals. These findings describing the most common composition of integrated care teams in the community are consistent with care models in which a psychiatrist provides indirect consultation to several behavior health professionals who support an even greater number of PCPs (

9). Thus indirect consultation allows the psychiatrist to leverage his or her expertise to reach a large population of patients (

5) through this team structure. Qualitative analysis is congruent with this finding, suggesting that working in this model increases psychiatrists’ ability to “intervene on behalf of more patients.”

Psychiatrists reported working in a team as a strength of this model. Success in team-based medical care hinges on effective communication among team members (

10), consistent with our results indicating that team members engaged in frequent scheduled and “as needed” communication. The importance of communication was reiterated in the advice psychiatrists provided, noting “availability [and] clear concise communication” are essential.

Our results suggest the potential for a broad scope of practice for psychiatrists in integrated care. For example, most psychiatrists reported that they were asked to address substance use disorders. Previous studies have also highlighted the need to address co-occurring substance use disorders among patients in primary care (

11). Our finding that respondents were also providing consultation regarding treatment strategies, such as managing general medical comorbidities and monitoring modifiable risk factors, suggested that integrated care has the potential to improve comprehensive health care for patients with mental illness. This is particularly important in populations with severe mental illness with comorbid general medical and behavioral health problems, who die approximately 20 to 30 years earlier than the general population (

12).

There were some limitations to the data collected. The survey method using a convenience sample may introduce selection bias. Findings were based on self-reports from participating psychiatrists and did not include objective measures of the activities of the participating psychiatrists. In addition, because the survey was openly available online, the number of possible respondents and response rate are unknown.