Clinical decision making is an important aspect of health care. A widely used categorization distinguishes between three levels of patient involvement in clinical decision making: paternalistic or passive (decision is made by staff, and the patient consents), shared (information is shared with the patient), and informed or active (staff informs, and the patient decides) (

1). Shared decision making (SDM) has a long tradition in health care (

2) and may contribute to better clinical outcomes (

3). In a randomized controlled trial, 59 patients with diabetes were encouraged to participate in therapeutic decisions (

4). At follow-up, these patients had better glycosylated hemoglobin values than patients in a control group. Another study investigated the effect of a decision aid regarding antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention (

5). Compared with patients in a control group, those in the intervention group had more realistic expectations about the risks and benefits of treatment and decided less often in favor of antithrombotic treatment.

SDM is also useful in the treatment of mental illness (

6). A brief intervention that was designed to prevent depression relapse and that included SDM was highly successful in improving outcomes (

7). Another study showed that SDM increased perceived active involvement in decisions reported by patients with schizophrenia and improved their attitudes toward treatment (

3). A systematic review of the effects of SDM found improvements in physical and psychological well-being and in satisfaction among patients with schizophrenia (

8). Patients with severe mental illness whose clinicians preferred active or shared decision making to passive decision making reported declines in unmet needs (

9).

Effective communication between patients and clinicians may lead to an increase in both treatment acceptance and satisfaction (

10). Some studies have found that the effect of SDM on treatment acceptance was completely mediated by satisfaction with the decision made (

11). Among patients with psychosis, reasons for preferring more active decision making were dissatisfaction with their psychiatrist or medical treatment (

12). Improvements in self-esteem were the most important correlates of service satisfaction for patients with psychosis, whereas clinical symptoms and unmet needs for health care played minor roles (

13).

Decision topics differ between acute and chronic illnesses (

14). Serious mental illnesses are long-term conditions, and topics discussed by the patient and clinician may change over time (

15). In addition to treatment, social issues and lifestyle management are important topics (

16). A previous study showed that decisions were implemented at different rates depending on the decision topic (

17). In the study reported here, we investigated how different decision topics influenced patient involvement in and satisfaction with decisions over a longer time period. Studies have shown that some patients prefer a collaborative role with their psychiatrist only for medical decisions, whereas they prefer an autonomous role in decisions about psychosocial interventions (

18). Psychiatrists, on the other hand, have been shown to prefer shared involvement for decisions about psychosocial interventions rather than medical ones (

19). How different topics influence involvement, satisfaction, and decision implementation is underresearched, and such studies can inform clinical practice (

20).

The aims of this study were to investigate from both patient and staff perspectives the stability of decision topics over time and the relationship between the decision topic, experienced involvement, degree of satisfaction, and decision implementation rate.

Results

The characteristics of the 588 patients are shown in

Table 1.The mean±SD illness duration was 12.5± 9.3 years, and the mean level of education was 10.4±1.9 years.

Of the 213 staff members, 76 (37%) were psychiatrists, 19 (9%) were psychologists, 11 (5%) were social workers, and 100 (49%) had other professions. A total of 123 (62%) were women, and the mean age of staff members was 45.1±11.2.

The 11 topics were reduced to three components with eigenvalues greater than 1, which explained 54% of the variance in the data. The three components were interpreted as treatment, social, and financial (

Table 2).

Only a portion of the patient and staff samples had complete information for the three measures across the seven follow-up points. For patients, the proportions were as follows: satisfaction, 23% (N=133); involvement, 22% (N=130); and implementation, 22% (N=129). For 213 staff members, the proportions were as follows: satisfaction, 44% (N=88); involvement, 44% (N=89); and implementation, 71% (N=142).

The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) estimated by GLLAMM were as follows: patient satisfaction, ICC=.24; patient involvement, ICC=.17; patient implementation, ICC=.09; staff satisfaction, ICC=.17; staff involvement, ICC=.26; and staff implementation, ICC=.14.

Stability of Topic Over Time

At each follow-up point, patients were asked to identify the most important decision topic. Among the 569 patients who did so at least once, the topic most frequently cited was in the treatment category (69% across all time points, range 67%−72%), followed by social (22%, range 20%−25%), and financial (9%, range 8%−10%). The patient-identified topic did not differ significantly by study time point, indicating good stability over time.

Relationship Between Topic and Involvement

A total of 543 patients identified a decision at one or more time points and also rated their involvement with that decision, providing 2,210 paired observations (patient-identified decision plus patient-rated involvement) across the seven time points. Patients with complete information for all time points (N=130) were more likely than those without complete information to have at least a secondary level of education (in the United Kingdom, ages 11–18) (13% versus 6%; χ

2=6.6, df=1, p=.01).

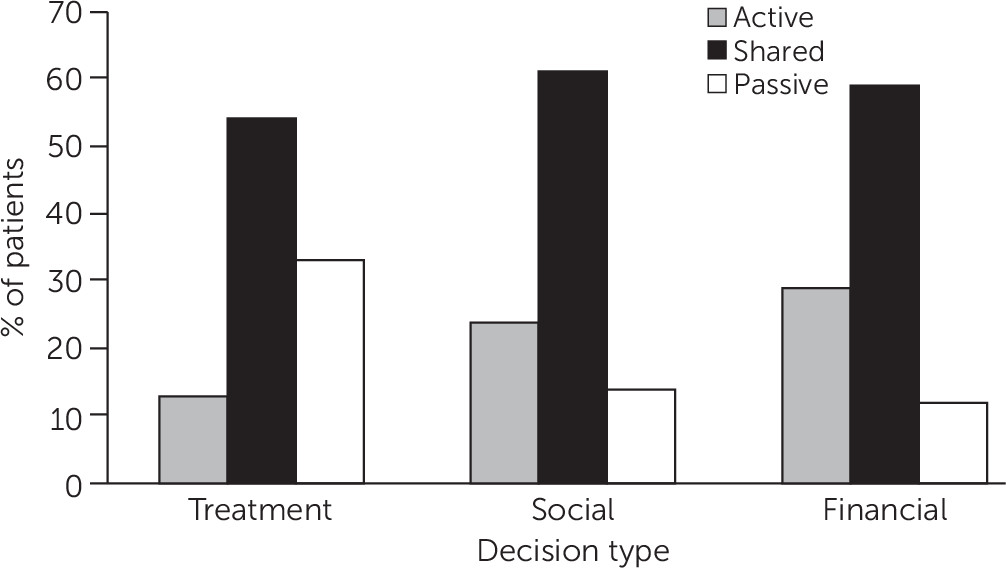

Figure 1 shows the level of patient-rated involvement in decisions, by topic, for the 543 patients. Patient-rated involvement differed by topic (χ

2=117.3, df=4, p<.001). Patients were more likely to rate their involvement as active rather than passive for social decisions (odds ratio [OR]=5.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.8–8.5, z=8.5, p<.001) and for financial decisions (OR=9.5, CI=5.1–17.5, z=7.1, p<.001), compared with treatment decisions.

A total of 512 patients identified a decision at one or more time points for which staff rated the patient’s level of involvement with that decision, providing 1,934 paired observations across the seven time points. The level of staff-rated patient involvement differed by topic (χ2=113.4, df=4, p<.001). Staff were more likely to rate patient involvement as active rather than passive for social decisions (OR=12.1, CI=7.2–20.2, z=9.4, p<.001) and for financial decisions (OR=14.8, CI=6.8–32.2, z=6.8, p<.001), compared with treatment decisions.

Relationship Between Topic and Satisfaction

A total of 545 patients identified a decision at one or more time points and rated their satisfaction with that decision, providing a total of 2,235 paired observations across the seven time points. Patients with complete information for all time points (N=133) were more likely than those without complete information to have at least a secondary level of education (13% versus 6%; χ2=6.9, df=1, p=.009).

Satisfaction differed by decision topic (χ2=11.7, df=4, p=.02). Patients were more likely to report higher levels rather than lower levels of satisfaction for social decisions (OR=1.5, CI=1.1−2.1, z=2.7, p=.01) and financial decisions (OR=1.7, CI=1.1−2.6, z=2.5, p=.01), compared with treatment decisions.

Relationship Between Topic and Decision Implementation

A total of 498 patients identified a decision at one or more time points and rated the implementation of that decision, providing 1,639 paired observations across the seven time points. Patients with complete information for all time points (N=129) were more likely than those without complete information to have at least a secondary level of education (11% versus 6%; χ2=4.1, df=1, p=.04).

Patient-rated implementation differed by decision topic (χ2=21.8, df=4, p<.001). Social decisions were more likely to be partly implemented (OR=3.0, CI=1.8−5.1, z=4.1, p<.001) or fully implemented (OR=1.7, CI=1.1−2.7, z=2.3, p=.03) than not implemented, compared to treatment decisions.

Patients with higher levels of education were more likely than those with lower levels of education to rate the decision as fully implemented (OR=1.8, CI=1.2−2.7, z=2.9, p=.004).

A total of 423 patients identified a decision at one or more time points that was also given an implementation rating by a staff member, providing 1,504 paired observations across the seven time points. Staff-rated implementation differed by decision topic (χ2=16.7, df=4, p=.02). Patient-identified social decisions were more likely to be rated as partly implemented than as not implemented (OR=2.2, CI=1.3−3.8, z=3.1, p=.004).

Discussion

In this six-country naturalistic study of community mental health services, decision topics identified as the most important from the last clinical meeting were categorized and found to be stable over seven time points in one year. The decision topic cited as most important by patients was treatment (69%), followed by social (22%) and financial (9%) topics. Topic was a significant predictor of patient-rated involvement, satisfaction, and implementation. Treatment-related decisions were consistently rated less positively. The same pattern was somewhat evident for staff ratings of patient-identified decisions.

The observed distribution of decision topics is consistent with that found in a previous study (

6). It remains unclear why social and financial decisions were cited less frequently than treatment decisions, because social and financial decisions are likely to have a major impact on long-term outcome (

25). A possible explanation is that only 5% of the staff members in this study were social workers, whereas nearly half were psychiatrists and psychologists, which may have led to a focus on treatment decisions.

As for involvement in decisions, patients were markedly more passive in treatment decisions than in social or financial decisions, which is also consistent with existing literature (

26). A previous analysis of the CEDAR data found that patients who were involved in decision making to an even greater level than they stated was desirable to them reported higher satisfaction, indicating that a clinical orientation toward empowerment may improve patient satisfaction (

27). Overall, higher involvement in and satisfaction with decisions not related to treatment may reflect a complex causal pathway (

28) in which both involvement and satisfaction are influenced by a range of factors, such as clinical variables and a history of contact with services.

Research on sociodemographic factors found that older patients reported a stronger desire than younger adults for involvement in decision making (

18). In contrast, our results showed no differences in sociodemographic variables in regard to decision topic or patient involvement. SDM generally aims at engaging patients to a greater extent in clinical decisions by decreasing the asymmetry between staff members and patients; but not all staff or patients feel comfortable about this balance (

19).

Social decisions were more likely to be partly or fully implemented than not implemented, which was not the case for treatment decisions. Previous analysis of CEDAR data showed the highest implementation rates for decisions related specifically to medication; however, this finding was based only on data from the baseline assessment and the initial two-month assessment (

17).

The main strength of the study is the large and multisite sample recruited from routine mental health services in six countries across Europe and assessed at seven time points. The use of convenience sampling means that participants may not be representative of the population; for example, clinician bias in referring patients to research studies and the tendency of more satisfied patients to participate in research may have affected the findings. The findings reported here need to be replicated in a random sample. Measures used were self-reported and did not include ratings of involvement by independent observers. Differing communication styles between professions may also have influenced the outcomes. Future research should record information on communication styles and explore this association. A further limitation is that more satisfied patients may tend to give more positive ratings. Finally, data on some measures may not have been missing at random; for example, the satisfaction measure consists of six items, which may have caused some patients to skip this measure. For this reason, multiple imputation could not be implemented for missing data, and instead we used a prorating approach when less than 20% of data was missing. Nonrandom missing data might be associated with selective noncompletion of a measure across time points; however, simulation results have shown that this marginally affects results (

29).

Conclusions

The decision topics cited as most important remained stable over one year, indicating that clinical interactions had a specific and continued focus over time. Patients reported poorer involvement, satisfaction, and implementation for treatment-related decisions than for social and financial decisions. This finding has important clinical implications. First, the lower patient ratings for treatment decisions may reflect their priorities. Individuals living with long-term disorders may require a focus on wider social and financial aspects of life. Qualitative investigation of how decision topics are chosen is needed. Second, different types of decisions were implemented at different rates, which suggests that clinicians may need to employ different interactional styles for different types of decisions (

20). We suggest that clinician-patient decision making in relation to social and financial decisions emphasize the goal-setting process in order to maximize goal attainability and striving by the patient (

30). By contrast, because involvement and implementation were more problematic for treatment-related decisions, a greater focus on behavioral and motivational aspects may be indicated. Development of a staff training program may benefit patients. In addition, decision aids are one approach to increasing patients’ knowledge about their illness and control over decisions (

19).

Future research could elaborate the relationship between decision topic and involvement, satisfaction, and implementation by evaluating whether disengagement or breakdown of the therapeutic alliance (as sources of low satisfaction) predicts a focus on treatment in clinical decision making, or whether current approaches to discussing treatment lead to negative outcomes that are not characteristics of discussions of social and financial goals. It would also be interesting to investigate the influence of illness severity on the decision-making process.