Permanent supportive housing (PSH) combines subsidized housing with wraparound supportive services. The housing is considered permanent (versus transitional), and supportive services facilitate housing stability among tenants (

1,

2). PSH is associated with a number of positive outcomes, most notably improved housing stability among individuals who previously experienced homelessness or who have a serious mental illness or substance use disorder, as well as decreased use of acute and expensive institutional services (

3,

4). Several studies report retention rates in PSH as high as 85% during the first year (

2,

5); however, fewer studies have identified factors that are associated with individuals’ ability to become housed.

Access to PSH has been conceptualized along a continuum, from having information about housing programs (

6) to being referred to a program and subsequently receiving a housing voucher (that is, a subsidy) (

7) and moving into a housing unit (

8–

11). Researchers have assessed access to housing as a dichotomous variable, indicating whether an individual met any of these outcomes (for example, received a housing subsidy) (

6), as well as the pace at which an individual moved from program admission to housing (

8–

11).

Studies of PSH generally—and of access to PSH specifically—have identified both individual- and structural-level factors related to housing access (

6,

12). Individual-level factors associated with increased access to housing subsidies include being female (

6,

7,

13), being black, and living with HIV/AIDS (

6,

13). Substance use is cited frequently as a barrier to accessing PSH; recent drug use may not prohibit application for or receipt of subsidies, but studies report a negative relationship between substance use disorders and living in PSH (

9,

13). Another study found that individuals with a history of substance use who participated in treatment were more likely to be referred to PSH and that those reporting recent substance use in the absence of treatment were less likely (

7).

The role of substance use in accessing housing may also reflect structural-level barriers; for example, unofficial policies of landlords or other “street-level bureaucrats” may require background checks, which may render tenants ineligible for private-market housing (

6,

13,

14). Other structural-level predictors of housing access—although not of long-term housing outcomes—include involvement with a more mature PSH program with experience accessing housing for “hard-to-house” tenants, as well as participation in case management and support services (for example, assistance with the housing search) (

7). Conversely, an experimental investigation of PSH found that regardless of level of case management intensity, individuals who received a permanent housing subsidy were significantly more likely to obtain permanent housing (

15). Limited research has assessed the role of other services but has found a negative relationship between accessing housing and the frequency of emergency department visits and inpatient medical admissions (

9).

Delayed access to housing may negatively affect longer-term housing stability: protracted placement processes (more than 80 days) are associated with decreased likelihood of becoming housed or employed (

10). Individual-level factors that may decrease the time required to become housed include being male and the presence of any major psychiatric disorder or a substance use disorder, whereas older age and seeking housing as a family have been found to increase the number of days between assessment by the PSH program and moving into housing (

11). From an organizational perspective, rapidly placing individuals in PSH may be difficult because of factors beyond the control of service providers, including logistics related to securing units and accessing financial assistance for move-in (

8).

This study aimed to further the existing research regarding both individual- and structural-level factors—particularly the role of supportive services—associated with access to housing and the pace of placement into PSH. This study used data collected in support of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program to address the following questions: Are there veteran characteristics that increase the likelihood of becoming housed, either at all or more quickly? Does receiving more services, through health care providers or case management, facilitate veterans’ access and time to placement in housing? And, if so, what programmatic changes could help more veterans get housed quickly?

Methods

This study used secondary quantitative data and primary quantitative and qualitative data collected from veterans participating in HUD-VASH at four locations (Houston; Los Angeles; Palo Alto, California; and Philadelphia). HUD-VASH combines a permanent housing subsidy provided through HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher Program and supportive services provided by VA clinicians, including assistance in locating, securing, and maintaining housing (

16). The general process for accessing HUD-VASH is assessment by VA staff, admission to the program and case management, referral to the public housing authority (PHA) to apply for the voucher, voucher receipt and housing search (typically 60–120 days), housing inspection conducted by the PHA, and moving into permanent housing. Veterans may select housing of their choice, most often obtained in the private rental market.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (IRB) and local study site IRBs.

Cohort and Subsample

The cohort comprised all veterans who were admitted to HUD-VASH case management and received a housing voucher (N=9,967) between 2008 and December 2, 2014, as documented in VA administrative data. Interviewers conducted in-person surveys with a subsample of the cohort (N=508); 110 of these veterans also participated in a longer semistructured qualitative interview. The study team identified veterans for interviews by consulting randomized lists of veterans enrolled in the program and veterans who had recently exited the program identified by case management staff; eligible veterans were mailed a recruitment letter, and interviewers followed up via telephone.

Data

Secondary data.

Secondary quantitative data for the study cohort were extracted from VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse, which stores administrative data related to diagnoses, outpatient encounters, inpatient admissions, and utilization of other VA services. The study assessed two primary outcomes: whether a veteran became housed through HUD-VASH and the number of days required to become housed, from program admission to moving into a housing unit.

Independent variables included sex, age, race, and ethnicity. The VA enrollment priority group was included as a proxy for income; it comprises five categories as indicated in

Table 1 and was entered into models as a dichotomous variable distinguishing those who did and did not receive VA compensation for a service-connected disability. Veterans’ service in Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) and combat experience reflect characteristics of their military service. Dichotomous variables indicated whether veterans had general medical or behavioral health diagnoses (

17).

Data on health-related service use—outpatient general medical, behavioral, and substance use services and emergency department visits—were collected for two time intervals: 0–90 days prior to HUD-VASH admission and 0–90 days following admission. For veterans who became housed, the average number of monthly case management contacts was measured for three time intervals: program admission to referral to PHA, PHA referral to voucher receipt, and voucher receipt to move-in.

Primary data.

The subsample of respondents provided data related to their perceptions of their experiences in HUD-VASH and their relationship with their VA case manager.

Analyses

Differences in veterans’ characteristics by whether they became housed via HUD-VASH (that is, “nonhoused” or “housed”) were assessed by using chi square tests and analysis of variance. A logistic regression for modeling whether the veteran was housed identified predictors of access to permanent housing. Among veterans who became housed, an ordinary least-squares multiple regression model estimated the time required to move into housing after program admission. Veterans with extreme values (more than three times the interquartile range) in the number of case management contacts or the number of days between admission and move-in were excluded from the analyses (<7% of any variable). Diagnostic tests were conducted to ensure that the regression analyses modeling time from admission to move-in did not violate normality. Dummy variables controlled for study sites in models.

A thematic analysis approach was used to identify themes within qualitative transcripts (

18).

Results

Veteran Characteristics

Most veterans in the cohort (85%) accessed permanent housing through HUD-VASH; 15% exited the program prior to accessing housing (

Table 1). Veterans who were not housed were significantly different from veterans who became housed; they were younger, more likely to identify as white or a race other than black, more likely to identify as Hispanic or Latino than non-Hispanic or Latino, more likely to have a service-connected disability of ≥50% and to have served in OEF/OIF, and more likely to have diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia and other psychoses, and alcohol use disorder. Veterans who were not housed had less frequent behavioral health and substance use visits 90 days pre- and postadmission, less frequent general medical visits postadmission, and more frequent emergency department visits postadmission.

The subsample of respondents who were interviewed in person had comparable characteristics with several exceptions: in the subsample, nonhoused respondents were less likely than housed respondents to identify as a race other than black. A higher proportion of housed respondents, compared with nonhoused respondents, had a service-connected disability of ≥50% and an alcohol use disorder, although these differences were not statistically significant (

Table 1).

Accessing HUD-VASH Housing

Table 2 presents results from a logistic regression model identifying characteristics associated with becoming housed. Having a service-connected disability, serving in OEF/OIF, having a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychosis, and having an emergency department visit in the 90 days after admission significantly decreased the odds of becoming housed. Receiving outpatient behavioral health care during the 90 days before admission and outpatient general medical, behavioral health, or substance use care in the 90 days after admission significantly increased the odds of becoming housed.

Days to Placement in HUD-VASH Housing

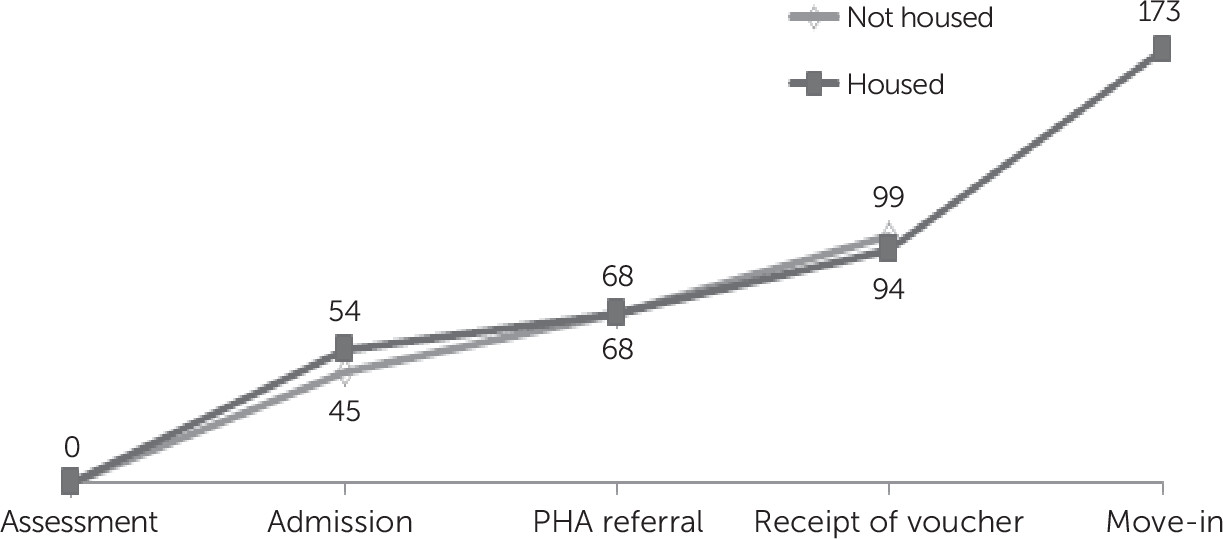

Figure 1 illustrates the average number of days required for HUD-VASH participants to move through the admission and housing process. Veterans who were not housed after being admitted to the program moved through the initial steps more quickly, but those who subsequently gained housing received their vouchers more quickly once they received a PHA referral. After voucher receipt, it took veterans who were eventually housed an average of 79 days to identify and move into housing.

Table 3 presents the results of a multiple regression model that identified factors related to the pace at which veterans proceeded through this process: veterans with a service-connected disability took longer than those without a service-connected disability and those with a drug use disorder took less time than those without one. Case management contacts during two periods—between admission and PHA referral and between voucher receipt and move-in—significantly decreased the time to becoming housed. Use of health care services was not significantly related to the time required to access housing.

Role of Case Management

In interviews, respondents described the assistance they received in HUD-VASH and their relationships with case managers. Significantly fewer nonhoused respondents indicated that they received assistance finding apartment options (

Table 4). Although nonhoused respondents reported significantly more monthly meetings with their case managers, a smaller proportion of nonhoused veterans than housed veterans agreed that their case managers were able to help them or that they agreed on goals.

During open-ended interviews, veterans who did not ultimately become housed through HUD-VASH described a lack of engagement with the program and supportive services. One nonhoused veteran said, “I was feeding my addiction, and I didn’t come back for about two months. I fell off the grid. I just went on with my addiction for a while. Drinking. . . . I just went out and lived in my car and on the streets.” Another said, “I was self-medicating. The VA wasn’t really sufficient as far as my PTSD and severe anxiety and all of that stuff goes. . . . I needed to show that I was trying to be as stable as possible in all the other areas without their help. I guess on my own.”

Veterans also described the importance of being able to trust program staff and the need for case managers to have a holistic understanding of their issues: A nonhoused veteran said, “When you have a VASH case worker that’s not willing to truly be there, I think it would really compromise it because a vet has to be able to trust somebody. . . . You have to have some rapport with that person. And if your rapport is based solely on nothing more than this person needs a service and I'm the person that gives him that service, then there's no rapport. There's no respect.” Another said, “I wish [HUD-VASH staff] had better knowledge of your medical conditions and what is going on, to better apply other resources to your specific situation. I think that was a lack of information shared between case managers . . . because you have this going on medically and you have this going on socially. They are both affecting each other.”

Alternatively, housed veterans described the interconnection of services that they took part in and how HUD-VASH helped them, as one veteran put it, “acclimate back into society.” One of the housed veterans said, “The Veterans Transition Center required you to be active in your medical care . . . . So I went to the clinic and I got my new providers there, my mental health provider and my primary care provider. In the process, I got a psychologist that signed me up for the HUD-VASH program.” Another housed veteran stated, “They put me in housing, raising my self-esteem, helping me with my issues, in order for me to maintain the housing. It is beautiful.” A third said, “Once I had my mind set on what I was going to do, there was no looking back, no accounting at all. They just were there for me. They had my back.” And a fourth noted, “They have allowed me to have a secure shelter with support and that is an emotional strength for me. And, they helped me acclimate myself back into society with their help. For a while I was in a culture that—it was not normal, and it takes you a little while to transition from that subculture to a social culture that you can function in.”

Housed veterans also discussed how case managers helped them during their housing search, from providing lists of available units and transportation to view units to assisting with interactions with landlords and completing paperwork. As one housed veteran stated, “[My case workers] also took me around if I needed transportation to get to certain places that were inaccessible by public transportation, they would take me to handle the biggest [parts of the process]. To actually get the paperwork started for me.” Another stated, “The staff, the ability to interact and to work with the staff and the counselors, and how easy they try to make the process on veterans, takes the stress out of it, the uncertainty out of the process and what you are going through and what you got to face, and any challenges you might come up against. They really try really hard to give you the best overview and the best options, and it is always your decision, but they put that out there for you. And, you cannot ask for any better than that.”

Discussion

Most veterans who received a HUD-VASH voucher ultimately found and moved into permanent housing. The outcome was partly explained by a number of individual- and structural-level factors. First, veterans receiving compensation related to service-connected disabilities had lower odds of becoming housed through HUD-VASH. Other studies have found that veterans receiving compensation related to a service-connected disability were more likely to maintain housing stability and less likely to return to homelessness (

19,

20). The lower odds of becoming housed among these veterans in our study may indicate that they became financially ineligible for housing assistance or that they had increased access to independent housing options because of their higher incomes, resulting in less need for a housing subsidy and perhaps a lack of interest in the supportive services attached to the subsidy.

Second, the presence of general medical and behavioral health conditions and related use of services during the 90 days after program admission—which overlapped substantially with the period after veterans received their vouchers and were conducting their housing searches—were significantly associated with becoming housed. Compared with their housed counterparts, veterans who did not become housed had higher rates of general medical and behavioral health conditions but were less frequently engaged in health care. However, a larger proportion of the nonhoused veterans used emergency department visits during these periods, suggesting a need for additional services, which veterans described during qualitative interviews. This finding corroborates another study that found a relationship between lack of adherence to outpatient care and not accessing housing (

9).

Third, the provision of supportive services decreased the time to placement in housing. Among veterans who accessed housing, those with a diagnosis of a drug use disorder moved in more quickly than those without such a diagnosis. This may indicate receipt of treatment or other support related to substance use, which has been reported elsewhere (

10). In addition, there was a relationship between the frequency of case management contacts—particularly during the period after voucher receipt and prior to move-in—and decreased time to housing. This finding is consistent with veterans’ responses during in-person interviews: those who became housed often reported that they received assistance finding apartment options and that their case managers were able to help them.

Although this study contributes to the literature about access to housing—specifically regarding the role of supportive services, and particularly engagement in health care and case management—it had a number of limitations. The analyses did not control for other individual-level characteristics often associated with housing instability or lack of access to housing, such as household composition, income, or prior incarceration. In addition, although the study tested an important program-level factor, it did not control for specific structural-level barriers, such as characteristics of the local rental market.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that providing pre- and postenrollment health care and case management to individuals in PSH programs has a significant impact on access to housing. A holistic approach to addressing general medical, behavioral, and substance use health care and supportive services may lead to improved outcomes for program participants. In particular, individuals with behavioral health conditions may require additional support throughout the housing process. The provision of outpatient care tailored to this population may decrease the frequency with which veterans do not complete the housing process (

9).

In addition, more intensive case management paired with innovative housing strategies to access housing would support rapid housing of veterans. Examples of strategies used in some HUD-VASH programs include deputizing case managers to conduct inspections, maintaining lists of preinspected housing units and landlords who are willing to rent units to high-need tenants, addressing some of the “street-level bureaucracy” identified in other studies (

6,

13,

14), and providing move-in assistance, such as providing transportation for the housing search and securing money for deposits.