In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published

Unequal Treatment, which served to elevate racial-ethnic health care disparities to the forefront of clinical and policy attention (

1). Eliminating health care disparities was also cited as one of the overarching goals of Healthy People 2010 and 2020 (

2,

3). Despite these efforts, disparities in mental health care remain wider than in most other areas of health care services (

4), and mental illness remains as one of the highest health burdens for minority populations (

5). Previous studies of trends found that although overall rates of mental health treatment increased, gaps in access to mental health treatment between blacks, Latinos, and non-Latino whites (hereafter referred to as whites) were sustained (

6,

7). In addition, Hispanic-white and black-white disparities were exacerbated in access to mental health care (

8). However, information regarding trends in mental health disparities beyond 2006 is limited. Updating our knowledge of trends in these disparities—and including Asian-white disparities—is critical for understanding whether efforts to decrease disparities have been fruitful. Such an update also provides a baseline for future studies evaluating the impact of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on reducing these disparities.

Since 2004, there have been significant shifts in the magnitude of expenditures and sources of payment for inpatient, outpatient, and medication therapies for mental illness in the United States. Growth in mental health care spending by private payers decelerated significantly in 2007–2009 compared with 2004–2006; state and local mental health care spending showed negative growth while federal mental health care spending accelerated (

9). During this time, major psychiatric medications, such as sertraline, risperidone, and quetiapine, came off patent (2006, 2007, and 2011, respectively) and prices decreased. Access to less expensive medications is one explanation for growth in psychotropic medication use in the overall U.S. population (

10). The impact of these overall trends on disparities in psychotropic medication use is unclear.

Discussion

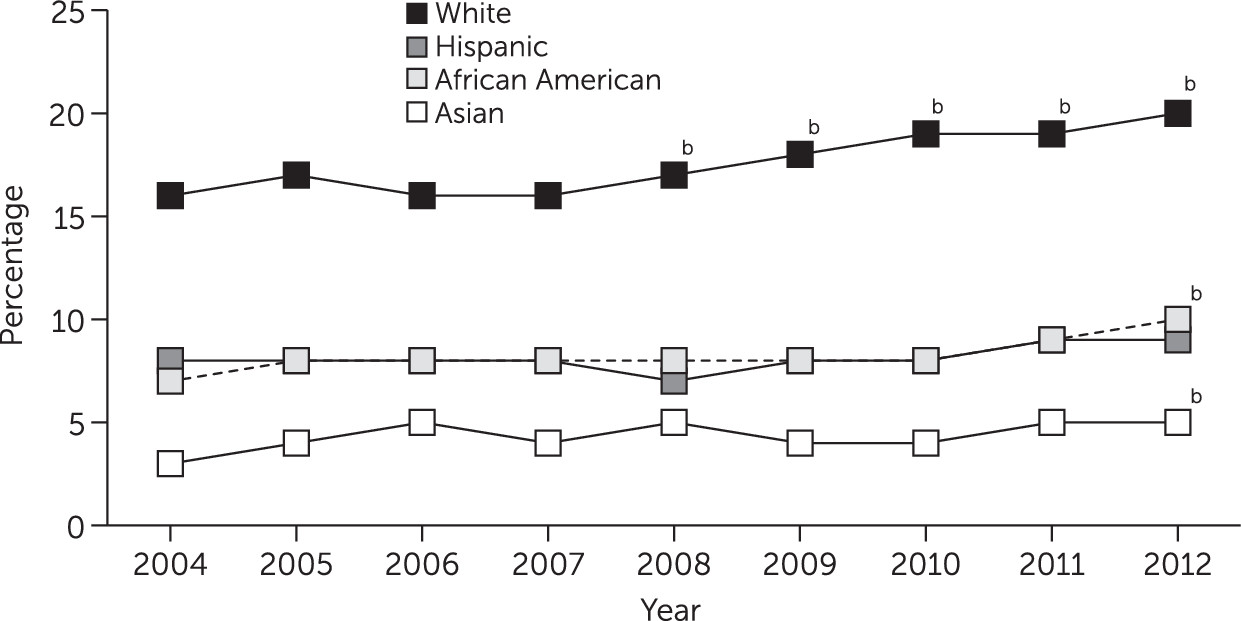

Little progress was made in reducing disparities in access to mental health care for blacks, Hispanics, and Asians compared with whites between 2004 and 2012. This was true for access to any type of mental health care, outpatient mental health visits, and psychotropic medication use, even after adjustment for racial-ethnic differences in clinical need. In the case of blacks and Hispanics, disparities in rates of access to any mental health care and any psychotropic medication were exacerbated over this period in absolute and relative terms. Asians had persistently lower rates of access to care across this period.

The widening disparities in any mental health care were predominantly driven by significant increases in psychotropic medication use among whites but not among blacks and Latinos. Only small increases in outpatient mental health care were noted among whites. Changes in ED and inpatient use for psychiatric diagnoses represented only a small percentage of total mental health services (less than 1% of the study population used these services). Our findings are consistent with analyses of national trends showing that use of prescription drugs, as well as antidepressants, increased broadly in the United States from 1999 to 2012 (

30). That blacks and Latinos did not participate in this increasing trend in psychotropic medication use may be due in part to the persistently higher uninsured rates among blacks (19% in 2012) and especially Hispanics (29%), compared with whites (11%) (

31).

Continued access disparities are of high clinical and public health significance given that persons from racial-ethnic minority groups, although generally having similar levels of mental illness prevalence as whites (

32), have greater persistence (

33) and severity of mental illness (

34), and because reducing racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care has been shown to lead to savings in expenditures for acute medical care (

35). The findings are similar to results from previous trends studies, which used data ending in 2004, that showed little progress toward reducing mental health care disparities for racial-ethnic minority groups (

6–

8). This suggests that calls to reduce mental health care disparities have not been successful (

1,

36–

38). These findings come at a time when renewed debate on racial inequality and social justice has given rise to increased discussion among health professionals that has identified inequality not only as a social justice issue but also as a public health problem, with tangible population and individual health consequences (

39–

42).

Our results may be explained by primary care providers' continued problems with detection of psychological distress among Asians, blacks, and Hispanics, compared with whites (

43,

44), suggesting that improved provider training in recognizing symptoms among racial-ethnic minority groups and standardized screening might help to improve provider recognition. Increasing managed care penetration (

45) and the supply of specialty providers in racially segregated communities (

45,

46) has been shown to be associated with decreases in racial-ethnic access disparities. Integrated health care initiatives may serve to address issues of recognition and provider supply through the colocation and cross-training of mental health professionals and primary care providers (

47) and the provision of mental health treatment by physician extenders, such as nurse practitioners and case managers (

48).

Financial and insurance barriers continue to interfere with access to high-quality care among racial-ethnic minority groups (

49), because persons from minority groups are more likely to report financial burden as a barrier to mental health treatment (

50). Medicare and Medicaid policies could begin to reverse these persistent trends, given that persons from racial-ethnic minority groups are more likely to have low incomes, to be Medicaid beneficiaries, and to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid benefits (

51–

53). Expanding Medicaid eligibility in states that have opted out of ACA Medicaid expansion, increasing primary care provider or specialist service reimbursement for Medicaid beneficiaries, and decreasing copays in these programs may reduce financial barriers to accessing care.

A secondary finding of note is that although disparities in access to mental health care worsened or persisted between 2004 and 2012, unadjusted mean scores on mental health scales did not change or even improved over time among racial-ethnic minority groups. Future research identifying the impact of access disparities on mental health outcomes is warranted, with attention to effects both at the mean and across the distribution of persistence and severity.

Disparities were consistently wider for Asian Americans than for any other racial-ethnic group. Asian Americans tend to report psychiatric symptoms only when they become severe and may report these symptoms in physical or psychosomatic terms, such as loss of sleep and fatigue (

54). Increasing clinician awareness of psychosomatic symptoms may improve recognition and treatment of mental illness among Asian Americans. Some barriers to mental health treatment may be more salient for Asian-American adults (

11), including cognitive processes (for example, failure to identify emotional distress as mental illness worthy of treatment), affective issues (for example, shame or stigma), cultural value differences (for example, possible conflicts between collectivist values and the individual orientation of psychotherapy) (

55), and fear of the stigma of mental illness, resulting in a reluctance to report psychiatric symptoms (

55,

56). In some Asian cultures, receiving treatment outside the family may be perceived as shameful, disgraceful, or a violation of the family hierarchical model (

56).

There is a need for future research to identify appropriate measures of fully informed preferences (

1,

57) and to isolate the portion of patient preferences related to past experiences of discrimination (

58). For example, categorizing Asian-white differences in cultural values as disparities may not be true to the IOM definition if these factors represent patient preferences (for example, a preference among Asians to treat mental illness with traditional or alternative medicines). However, differences in values could also be regarded as unallowable differences: Asian communities may receive less information about the efficacy of mental health care, and Asian Americans with mental illness may experience double external stigma from the majority group both for being a member of a racial-ethnic minority group and for living with mental illness (

59). Preferences for type of treatment may also play an important yet underexamined role. If persons from minority groups prefer psychotherapy over medication and face a shortage of trained psychotherapists—and if researchers should adjust for this preference—then our analysis overestimates the disparity in access to any mental health care. On the contrary, we are likely to underestimate disparities by not adjusting for greater preferences for receiving care from primary care providers among patients from minority groups (

60,

61) given that there is a relatively greater availability of such providers compared with specialist mental health providers.

This study had several limitations. First, we adjusted for differences in clinical appropriateness and need across racial-ethnic groups by using available mental health measures in the MEPS that have high sensitivity and specificity for mental illness (

19–

21); however, these are not gold-standard diagnostic measures. Second, we had little information on disparities in the quality of care once persons were in treatment. Third, geographic information in the MEPS is limited to identification of four U.S. regions. Thus our analysis did not allow us to consider the important role of state- and community-level differences found in prior studies of mental health care disparities (

45,

62). Fourth, the MEPS excludes homeless individuals and those in institutions and does not accurately measure undocumented immigrant status (which would be a large barrier to access). Fifth, our analysis predated the main implementation of the ACA, which should improve access to mental health care and reduce disparities because it aims to increase insurance coverage, contribute resources for establishing mental health clinics to communities with large racial-ethnic minority populations, and invest in a more diverse mental health care workforce.

Despite these limitations, we present evidence that little progress has been made between 2004 and 2012 in reducing mental health care access disparities in the United States. Persons from racial-ethnic minority groups, even after analyses adjusted for clinical need, continued to access mental health care at lower rates than whites. For Hispanics and blacks, this gap in access increased between 2004 and 2012 for any mental health care and psychotropic medications. Given stagnant progress in reducing disparities and increases in disparities for some populations, renewed attention to identifying interventions that improve access to mental health care for racial-ethnic minority groups is urgently needed. In addition, given the breadth of access disparities, clinically oriented interventions that improve the quality of mental health care for minority populations should also be evaluated to understand their broader impact on future community rates of access to care.