Individuals with serious mental illnesses who receive inpatient psychiatric treatment are at high risk of experiencing adverse events and poor outcomes during the period immediately following discharge (

1). These risks are especially concerning given the low rates of successful transitions from hospital to outpatient psychiatric care in this population. Studies have shown that only 30% of adults with Medicaid receive follow-up care within seven days of a psychiatric hospitalization and that only 42% to 49% receive such care within 30 days of hospital discharge (

1,

2). Not surprisingly, payers and accrediting bodies have looked to hospitals to implement discharge planning practices to increase the rate of timely transition to outpatient treatment.

Routine discharge planning practices include communicating with outpatient providers regarding treatment plans, scheduling timely appointments for outpatient follow-up care, and forwarding discharge summaries to outpatient providers. Although these practices are widely endorsed as a standard of care for hospitalized patients (

3,

4), there is little empirical research documenting the extent to which these practices are provided in routine care and whether they influence care transitions. Communication by hospital staff with outpatient providers and timely scheduling of initial outpatient visits following discharge have been associated with improved attendance at outpatient psychiatric services (

5,

6). However, one study of standardized discharge planning contacts pre- and postdischarge for individuals with multiple readmissions found no impact on readmissions or engagement in outpatient services (

7).

This study examined associations between routine discharge planning practices and time to treatment follow-up after discharge for 17,053 psychiatric discharges. We hypothesized that receipt of more discharge planning practices would be associated with greater likelihood of entering outpatient treatment following discharge and less time between discharge and the first psychiatric outpatient follow-up visit.

Methods

The New York State (NYS) Medicaid program transferred management of behavioral health benefits for individuals receiving federal Supplemental Security Income benefits to managed care plans beginning in 2015. NYS wished to collect baseline data regarding discharge planning practices by hospital providers prior to the managed care transition. It contracted with five managed behavioral health care organizations (MBHOs) to review psychiatric admissions in defined geographic regions in 2012–2013. The MBHOs reviewed psychiatric admissions of patients whose care was covered by fee-for-service arrangements, excluding admissions of individuals who were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare and those who were admitted to state-operated psychiatric hospitals. The MBHOs neither authorized nor paid for hospital services. NYS required hospital providers to notify the regional MBHO of each psychiatric admission and review care coordination and discharge planning needs with an MBHO care manager (via telephonic concurrent review). The MHHO care manager documented whether the hospital provider contacted a current or prior mental health outpatient provider, scheduled an aftercare appointment, and forwarded a discharge summary to the outpatient provider. Documentation of completion of each of the practices was based on hospital providers’ self-reports (yes/no). We did not analyze information about when the practices were completed or the timeliness of scheduled aftercare appointments relative to the discharge date.

Discharge records for a one-year period (July 2012–June 2013) were selected (N=24,034). Discharges to institutional settings (N=2,913)—for example, nursing homes, residential treatment centers, and state-operated psychiatric hospitals—were excluded because the study focused on the transition from inpatient care to outpatient community-based care. Discharge records missing a Medicaid identification number or for persons who did not have continuous Medicaid eligibility for at least 45 days postdischarge were excluded (N=4,068). The final study cohort included 17,053 discharges.

Outpatient mental health service use following hospital discharge was documented from Medicaid claims data. Mental health treatment services were defined as any visit to a clinic or specialty behavioral health service licensed by the state mental health authority or any outpatient service for a primary diagnosis of mental illness that was provided by a mental health practitioner or physician. The primary outcome was a continuous measure of time to first psychiatric outpatient treatment follow-up during the first 45 days after hospital discharge. To calculate rates of follow-up, we also categorized the outcome by whether the visit occurred within the first seven or 30 days following discharge. Predictors included dichotomous (yes/no) indicators for each of the discharge planning practices and a separate variable created to reflect the total number of practices that were implemented (range 0–3).

Survival analysis was used to examine whether the number of discharge planning practices (all three, any two, one, or none) were associated with time to the first outpatient visit. A Cox proportional-hazards regression model was fitted to examine the effects of the practices on time to first follow-up visit. All data management and analyses were performed by using SAS, version 9.4. The NYS Office of Mental Health Institutional Review Board determined that this analysis did not constitute research involving human subjects.

Results

The 17,053 discharges included 12,199 unique individuals, of whom 3,971 (33%) had two or more inpatient discharges during the study period. Of all discharges, 56% (N=9,625) were male patients, 76% (N=12,954) were adults (defined by NYS Medicaid as ages 21 and over), and 24% (N=4,099) were youths (under age 21). The most common primary discharge diagnoses reported by providers were schizophrenia and related disorders (N=7,055, 41%), depressive disorders (N=3,876, 23%), and bipolar disorder (N=2,779, 16%). Hospital providers reported having contacted a current or prior outpatient mental health provider for 70% (N=11,915) of discharges; having scheduled an appointment for outpatient mental health treatment prior to discharge for 82% (N=13,981) of discharges; and having forwarded a discharge summary to an outpatient provider for 85% (N=14,495) of discharges.

Thirty-five percent of discharges of adults and 48% of discharges of youths were associated with keeping an outpatient appointment within seven days of discharge, and 55% of adult discharges and 65% of youth discharges were associated with keeping an outpatient appointment within 30 days of discharge, similar to rates reported in prior studies of Medicaid populations (

1,

2).

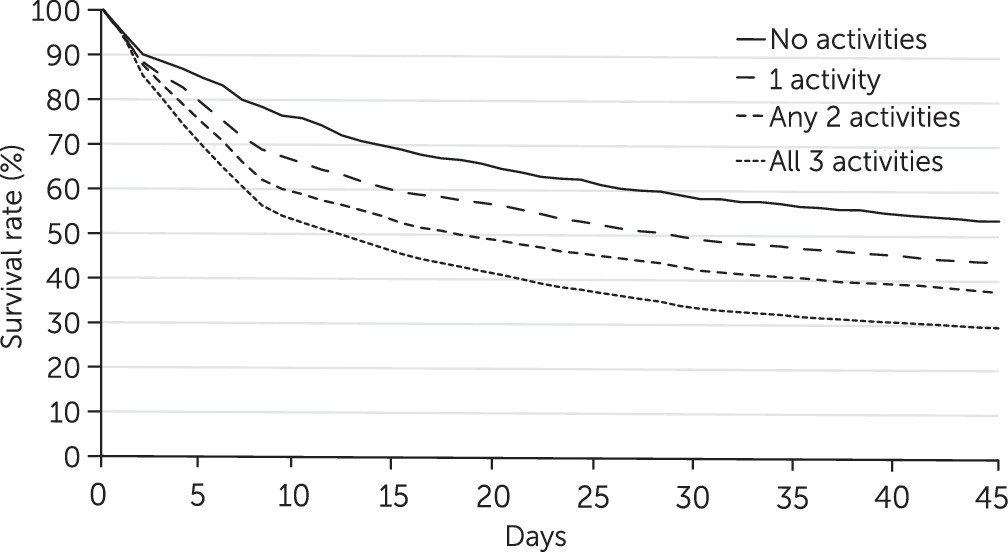

Figure 1 displays the results of a survival analysis comparing the time to first follow-up visit among all discharges, grouped by number of discharge planning activities (none, one, any two, or all three). The group differences were statistically significant (log-rank test χ

2=285.63, df=3, p<.001). The four groups appeared to separate by day 3 following discharge and to diverge between days 3 and 8, with individuals who received more discharge planning activities showing more rapid connections with aftercare. The differences between the four groups were little changed after day 9. The median time to initial follow-up appointment was 12 days for discharges associated with all three activities, 18 days for discharges associated with any two activities, and 28 days for discharges associated with only one activity. The cohort of discharges associated with none of the practices had the lowest rates of follow-up; for 50% of discharges in this group, there was no aftercare appointment in the 45-day follow-up window.

A Cox proportional-hazards regression modeled time to first postdischarge follow-up as a function of number of discharge planning practices (none, one, any two, or all three). The regression model fit was significant (likelihood ratio test statistic=290.13, df=3, p<.001). Among discharges associated with one discharge planning practice, the individual received his or her first outpatient visit approximately one-third faster compared with discharges associated with no discharge planning practices (hazard ratio [HR]=1.32, p<.001). The first follow-up visit occurred nearly twice as fast for discharges of individuals who received all three practices compared with no practices (HR=1.96, p<.001).

Discussion

There is widespread acceptance of basic discharge planning practices as a standard of care. However, few studies have documented the frequency with which these practices are provided in routine care and their associations with timeliness of first outpatient visits following discharge. We found that hospital providers reported completing at least one of the three discharge planning practices for 85% of discharges, and there was a significant association between number of discharge planning practices and speed to first outpatient visit.

Discharge planning rates were substantially higher than the rates reported for general medical and surgical providers. A literature review noted that outpatient primary care providers receive a continuing care plan within one week for only 15% of discharged patients, and up to 25% of continuing care plans never reach outpatient providers (

8). These differences may reflect a greater perceived need for communication among hospital psychiatric providers, given the psychosocial factors that often play a key role in the onset and treatment of psychiatric conditions. It is also possible that the concurrent review of mental health admissions, with its focus on determining care coordination needs and documenting provider discharge planning practices, increased the prevalence of these discharge planning practices.

Our findings suggest that routine provider discharge planning practices improve successful care transitions. These practices appear to exert a short-term effect during the first week following discharge, a key high-risk period for treatment discontinuation. This finding has face validity; one would not expect routine discharge planning practices to influence treatment trajectories over longer periods following discharge, when other clinical factors (such as substance use and lack of awareness of need for treatment) and social and environmental factors (such as lack of transportation) are more likely to influence health-seeking behavior.

For many individuals, routine discharge planning practices may be necessary and sufficient to ensure successful care transitions. However, for 45% of discharges involving adults and 35% of discharges involving youths, the patient did not attend an initial aftercare appointment within 30 days of discharge. For individuals with more severe illnesses, comorbid conditions, housing instability, or multiple care coordination needs, routine discharge planning practices may have little impact on transition to outpatient care. These individuals likely require intensive care transition interventions that have been shown to improve linkages to outpatient services for general medical and surgical patients (

9,

10) and for psychiatric patients (

11,

12) at high risk of readmission. Further research that determines the best time to use intensive care transition interventions and how to tailor the use of specific interventions for individual patients will allow providers to better align scarce resources.

This preliminary analysis had several limitations. The sample included only Medicaid recipients; measurement of the discharge planning practices was based on provider report, yet providers received no standardized guidance as to what constituted the contacts and communications called for in these practices; and we were unable to document timeliness of the specific practices relative to the discharge date. Although the MBHOs conducted telephonic concurrent review, they were unable to independently confirm that hospital providers completed each activity. A significant number of individuals had two or more discharges during the 12-month period, and no adjustment was performed for the lack of independence of these observations. Importantly, we were unable to control for key individual, provider, and service system characteristics that may influence postdischarge follow-up, including gender and ethnicity (

13), co-occurring substance use (

1,

13,

14), lack of contact with psychiatric providers prior to admission (

1,

2,

15), and availability of outpatient psychiatric providers (

1,

14). Finally, the clinical consequences of accelerating the speed to first follow-up visit remain unknown.

Conclusions

This study provided preliminary evidence of an association between commonly required discharge planning practices (contacting a current or prior mental health outpatient provider, scheduling an aftercare appointment, and forwarding a discharge summary to the outpatient provider) and the likelihood and timeliness of the first outpatient appointment following a psychiatric hospitalization for individuals with Medicaid. Future research should control for important confounding factors that may affect the likelihood that highly vulnerable individuals will access outpatient treatment soon after discharge from hospital psychiatric care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dana Cohen for assistance with manuscript preparation.