Virtual reality interventions are emerging as evidence-based and highly scalable approaches to enhance skills and outcomes among individuals with severe mental illness or individuals who are on the autism spectrum. SIMmersion, L.L.C., developed virtual reality job interview training (VR-JIT) by using recommendations from vocational-rehabilitation experts (

1) and a theoretical model of job interviewing (

2) (

www.jobinterviewtraining.net). Moreover, VR-JIT integrates neuroscience-based learning principles that include repeated practice, hierarchical learning across progressive degrees of difficulty, and a reward system to reinforce behavioral change (

3).

We conducted four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the efficacy of VR-JIT in improving interviewing skills for individuals with psychiatric disorders (for example, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorder ([ASD]) or veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We found that completion of VR-JIT improved interview performance between pretest and posttest for trainees in each cohort (

4–

7). Trainees in each cohort had greater odds of receiving a competitive job offer (

5,

8) or an offer for a competitive volunteer position or job at six-month follow-up compared with members of the comparison groups (

9). Moreover, we observed a VR-JIT dose effect in two cohorts—completing more virtual interviews was associated with greater odds of getting a job offer (

8).

Although we hypothesize that more training led to better interviewing skills, which in turn resulted in more job offers, the association between training and job offers could be explained by other nonspecific mechanisms (for example, people who persisted in training also persisted in job searching). Understanding the relationship between interviewing skills and job offers in a sample of individuals with severe mental illness or on the autism spectrum seeking employment is of interest because a thorough literature review found no previous study demonstrating this connection. Job interview training is widely believed to be important for job seekers, a belief that seems rooted in common sense. Yet, there are no scientific reports on whether interviewing is a mechanism of employment.

Mediation analyses have lower statistical power than tests of main effects, so to increase power, we combined the data from four cohorts to assess whether improved interviewing skills among trainees is a mechanism for obtaining a job offer. Our primary hypothesis was that posttest interviewing performance mediates the relationship between the number of completed virtual interviews and receiving a job offer. We also examined whether there was evidence of heterogeneity in the mediated effect across trials.

Methods

Participants included 79 individuals (including veterans) who had been diagnosed as having a mood disorder (depression or bipolar disorder), PTSD, schizophrenia, or ASD and who were assigned to the training group in four RCTs evaluating VR-JIT from January 2012 to May 2014. There were 119 participants across the four studies, including 40 participants in the multiple comparison groups. The mean±SD age of participants was 43.1±14.8 years, 56 (71%) were male, 47 (59%) were African American, 26 (33%) were Caucasian, and six (8%) were Latino, Asian, or biracial. Participants’ parents had a mean of 13.5±3.1 years of education, which served as a proxy of socioeconomic status. Additionally, eight (10%) participants were never employed or were underemployed, 14 (18%) had been unemployed for six months or less, 11 (14%) had been unemployed for seven to 23 months, 32 (40%) had been unemployed for 24 to 59 months, and 14 (18%) had been unemployed for 60 or more months.

ASD and other psychiatric diagnoses were confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; Social Responsivity Scale, second edition; and clinical records. All participants were clinically stable. Inclusion criteria included ages 18 to 55, minimum sixth-grade reading level (determined by the Wide Range Achievement Test 4), willingness to be video-recorded, being unemployed or underemployed, and having demonstrated active seeking of employment. Exclusion criteria included having a medical illness that compromised cognition (such as traumatic brain injury), uncorrected vision or hearing problems, or active difficulties with substance abuse.

We randomly assigned participants by a ratio of 2 to 1 into the training or control groups. Measurements collected at pretest, posttest, and six-month follow-up are described below. After six months, we approached participants and asked them to complete a brief survey in person, over the phone, or by e-mail. All participants provided informed consent, and Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board approved the protocol. Additional methodological details are reported elsewhere (

5–

7).

VR-JIT is based on eight learning goals that fit within Huffcutt’s (

2) theoretical framework for successful job interviewing. Four goals emphasize job-relevant interview content (conveying oneself as a hard worker, being easy to work with, behaving professionally, possessing negotiation skills), and four goals emphasize interview performance (sharing things positively, sounding honest, sounding interested in the job, and appearing comfortable during the interview) (

4,

6,

7). Trainees learn about interviewing skills from online didactic lessons and by practicing these skills during their interactions with “Molly Porter,” a virtual human resources agent from a fictional store called Wondersmart.

VR-JIT scores each virtual interview from 0 to 100 on the basis of how well the trainee performs on the eight learning goals. Trainees also received in-the-moment rewarding feedback from a virtual job coach about a response’s appropriateness. After each virtual interview, trainees reviewed their scores and received automated positive reinforcement and constructive feedback on their performance for each learning goal. Last, trainees were required to score 90 or better at each level of difficulty (easy, medium, and hard) within three attempts before progressing to the next level. After five attempts at the same level, trainees automatically advanced to the next stage of difficulty if they did not score a 90 or better. Training occurred during five visits across five to 10 business days.

Research staff recorded the number of completed virtual interviews with Molly. The number of completed virtual interviews was considered a proxy for the dose of training. Trainees completed 14.8±3.5 virtual interviews.

Participants completed two mock job interviews with a professional actor at pretest and two mock job interviews at posttest during the RCTs. The posttest measurement was evaluated as the mediator for this study. We assessed performance across nine domains that overlap with the eight learning goals, with the ninth domain assessing overall rapport with the interviewer. The videos were randomly assigned to two raters, blind to condition, with more than 15 years of experience in human resources. Total scores for the nine domains were computed for each video (score of 1 to 5 per domain), and the scores of the two videos were averaged to provide a single score for each time point. Additional methodology (including scoring manuals) on the posttest mock interview measurement can be found elsewhere (

6,

7).

We evaluated neurocognition, measured by the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status total score, and the self-reported number of months since prior employment as covariates, given that they are associated with vocational outcomes (

10,

11). We also evaluated diagnosis as a covariate, given the variety of diagnoses among trainees.

At six-month follow-up, we surveyed participants and asked them whether they had received a job offer since completing the study.

We used a Bayesian estimator to conduct a mediational path model with Mplus 7.2 because of the estimator’s robust performance under conditions of smaller sample sizes compared with maximum-likelihood estimation and the Sobel test. Model fit for Bayesian estimation uses the posterior predictive checking method; a posterior predictive p (PPP) value above .05 indicates a good fit. To assess the statistical significance of mediation by using the Bayes posterior credible interval (PCI), the specified indirect effect is considered significant if the PCI does not contain 0 (

12). We also examined heterogeneity in mediation across trials (

13). [Citations for the assessments and information about tools discussed in this section are available in an

online supplement to this report.]

Results

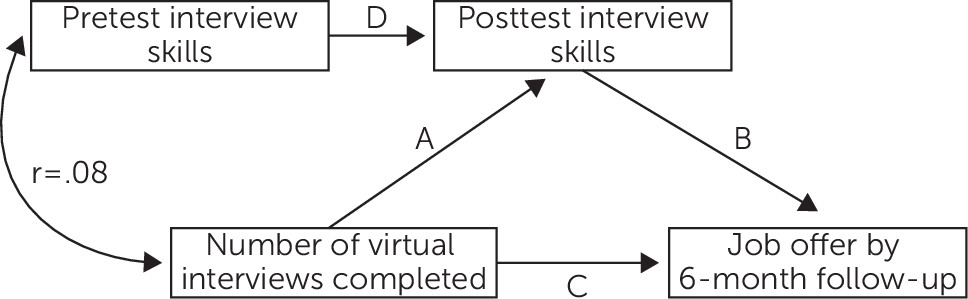

Our mediation model provided a good fit to the data (PPP=.47) when we accounted for pretest interview skills. Pretest and posttest interview skills were highly correlated (r=.82, p<.001) (

Figure 1, path D). Diagnosis, neurocognition, and months since prior employment were removed as covariates because they did not explain significant variation in the model. We observed a significant mediation effect whereby the number of completed virtual interviews predicted posttest interviewing skills, which in turn predicted receiving a job offer by six-month follow-up (product of coefficients=.02, SD=.01, β=.02, p<.05; 95% PCI=01–.04) (

Figure 1). The relationship between number of virtual interviews completed and job offer attainment was fully mediated by posttest interviewing skills (

Figure 1). As indicated by path C, the direct effect between completed interviews and job offer changd from significant (B

=.09, p<.05; SD

=.046, β=.30, 95% PCI=.01–.54) to nonsignificant. No evidence of heterogeneity in mediation across trials was found (that is, the strength of the hypothesized mediation pathway was of similar magnitude across the included trials). We conducted a second mediation analysis while accounting for potential heterogeneity of the meditational paths when combining data from multiple trials (

13). The results were very similar (95% PCI=–.01 to .05) and add to our confidence in a mediated effect.

Discussion

Standardized vocational-rehabilitation programs, such as individual placement and support, use several mechanisms (such as job development) to help clients obtain employment (

14). We conducted a mediation analysis to evaluate whether VR-JIT provides evidence that job interview training is a mechanism for helping trainees obtain employment. The results support our hypothesis that job interviewing skills fully mediated the relationship between completed virtual interviews and obtaining a job offer. Specifically, we observed that performing more virtual interviews enhanced job interviewing skills, which predicted a greater likelihood of receiving a job offer. Although diagnosis was not a significant covariate, according to our observations, a mediation analysis using a larger sample could test whether the mediation results observed in this study varied by diagnosis.

Prior studies suggested that VR-JIT trainees from individual cohorts had greater odds of receiving a job offer. Trainees across all four cohorts had increased odds of receiving a job offer [see online supplement]. However, the current study identified the relationship between the number of completed virtual interviews and improved interviewing skills as the mechanism for getting a job offer. To our knowledge, this is the first study to confirm that job interview training is related to getting job offers. Although we did not evaluate a large enough sample to determine the optimal dose of interview training, we found that completing three to five sessions was sufficient for most trainees to significantly improve their interviewing skills. VR-JIT provides scores, feedback, and hierarchical training so that dose can be adjusted depending on individual performance. Perhaps some trainees maximize their benefit with fewer hours of training, whereas others may need more training to acquire the same skill level.

The results should be interpreted while considering some limitations. The trials were conducted in a laboratory setting; hence, the findings may not generalize to community settings. Also, the samples were small and did not include individuals at an early-onset stage of their disorder. Participants needed at least a sixth-grade reading level to use VR-JIT, so the findings may not generalize to individuals with lower reading ability. Last, several other mechanisms of improved skill and outcome (such as motivation and anxiety) have been identified as barriers to employment (

15), but they were not measured in these trials. However, future research can evaluate these factors as possible mediators of the relationship between training and receiving a job offer.