Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including neglect, abuse, and family dysfunction, are overrepresented in the histories of homeless individuals (

1,

2). In fact, some researchers assert that exposure to adversity during childhood and adolescence is the primary trigger for leaving home and early homelessness (

3), which may increase the risk of involvement with antisocial peers, substance abuse, deviant subsistence strategies, and risky sexual behaviors (

4). Therefore, homeless individuals who have been exposed to childhood adversity are expected to be at substantially greater risk of criminal justice involvement and victimization than individuals without such experiences.

Among homeless individuals, a history of childhood abuse and neglect has been found to increase the risk of physical or sexual victimization (

2,

5) and instances of intimate partner violence (

6,

7). Some researchers have suggested that a child exposed to unhealthy relationship dynamics (for example, physical abuse of loved ones) may assume this behavior to be normal and may then become assimilated into unhealthy and abusive adult relationships (

8) with increased risk of victimization. Other authors have asserted that additional factors, such as amount of time at risk, deviant peer affiliations, participation in deviant subsistence strategies, trading sex, and symptoms of mental illness, mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and later victimization of homeless persons (

9,

10). In addition, homeless individuals are more likely than the general population to suffer from a psychiatric disorder, such as schizophrenia, a substance use disorder, and major depression (

11), which may also adversely affect their ability to avoid risky situations and unsafe relationships. Severe mental illness has been identified as a major risk factor for victimization through multiple individual and environmental pathways (

12,

13).

A history of childhood physical abuse has been found to significantly increase the risk of delinquent behaviors, arrest, incarceration, and negative police encounters among homeless individuals (

14–

16), even after control for the significant impact of drug use, deviant peer interactions, and deviant survival behaviors (

17). In addition to physical abuse, other types of adversity also increase the risk of criminal justice involvement among individuals who experience homelessness. For example, a study of 5,774 homeless persons with severe mental illness found that exposure to childhood emotional or sexual abuse was associated with higher rates of incarceration (

16). Moreover, exposure to emotional neglect during childhood increased involvement in delinquent activities, such as violence and stealing (

18), and was found to be associated with elevated incarceration rates (

19) among homeless individuals. Overall, evidence suggests that early exposure to adversity may have an enduring effect on individuals’ propensity to become involved in the criminal justice system later in life (

20).

Although research has shown that homeless individuals with histories of ACEs are at higher risk of involvement in the criminal justice system and victimization, there is a dearth of literature in this area. Specifically, most research on the relationship between ACEs and both criminal justice involvement and victimization has focused on homeless youths (

6,

7). Many studies also suffer from important methodological limitations, including small samples and a failure to control for other factors that may affect the rate of criminal justice involvement and victimization among homeless adults. Notably, most previous research has focused on investigating crimes committed by homeless persons rather than on their high vulnerability to victimization; specifically, there is a lack of research examining justice involvement and victimization in the same sample (

21). Finally, there is a need to examine the impact of different types of ACE, including neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and the diverse forms of dysfunctional household events that are associated with elevated risks of subsequent criminal justice involvement and victimization.

This study aimed to address important gaps in the literature by investigating the differential effect of various ACEs and cumulative effects of ACEs on criminal justice involvement and victimization in a large sample of homeless adults with mental illness, while controlling for sociodemographic factors, psychiatric diagnoses, and duration of homelessness. We hypothesized that all types of ACE are associated with a higher rate of criminal justice involvement and victimization in the past six months and that a history of cumulative ACEs is associated with a higher rate of criminal justice involvement and victimization in the past six months.

Methods

Participants

This study was part of the At Home/Chez Soi project, which included 2,255 participants from five Canadian cities: Toronto (25%), Vancouver (22%), Winnipeg (22%), Montreal (20%), and Moncton (9%) (

22). Participants were eligible to participate if they were over 18 or 19 years old (depending on the province), were absolutely homeless or precariously housed, and met criteria for a mental illness at the time of enrollment. Those with no legal status as a Canadian resident, landed immigrant, refugee, or refugee claimant and those who were currently a client of another assertive community treatment or intensive case management team were excluded from the study. Participants were recruited from a wide variety of settings, including the street, shelters, and day centers, and from hospital referrals between October 2009 and June 2011.

A total of 367 participants (28% female), representing 16% of the total sample, were excluded because of invalid responses on the questionnaire about ACEs. Thus our final sample included 1,888 (32% female) participants. Analyses confirmed that the excluded participants were not significantly different in terms of sociodemographic factors or duration of homelessness from those who provided valid responses on the ACEs questionnaire. However, the rates of alcohol and drug dependence were lower among the excluded individuals (p<.05 for both) and the rate of psychotic disorders was higher (p<.05).

Measures

Sociodemographic and background information.

Sociodemographic characteristics and duration of homelessness (that is, lifetime homelessness, longest single period of homelessness, and age at first homelessness) were collected at baseline with the Demographics, Housing, Vocational, and Service Use History questionnaire, which was developed for the demonstration project (

22). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview 6.0 (MINI) was used during enrollment to assess the presence of axis I psychiatric disorders (

23).

ACEs.

The ACEs questionnaire retrospectively assesses exposure to ten types of childhood adversity that occurred before age 18, including neglect (physical and emotional), abuse (emotional, physical, and sexual), and household or familial dysfunction (household mental illness, household substance abuse, mother treated violently, parental separation or divorce, and incarcerated family members) (

24). The ACEs questionnaire provides dichotomous (yes or no) responses for each item. To create a cumulative ACEs score, responses from all ten items are summed (

24).

Criminal justice involvement and victimization.

The sections on use of justice services, arrest, court appearances, and victimization of the Health, Social, and Justice Service Use (HSJSU) inventory, which was also developed for the study (

22), were used to assess the occurrence of criminal justice involvement and victimization in the past six months. Two dichotomous dependent variables were created: criminal justice involvement and victimization. Criminal justice involvement referred to any involvement in the past six months (versus no involvement) and was computed from summing the scores for detention by police without being held in a cell, held in a police cell for 24 hours or less, arrest, and court appearance. Any victimization in the past six months (versus no victimization) was computed from summing the scores for victim of robbery, threatened, victim of a physical assault, and victim of a sexual assault. The HSJSU also assesses the frequency and nature of or reason for the incident in each category.

Procedure

At Home/Chez Soi was a research demonstration project providing Housing First and recovery-oriented services and supports to homeless adults with mental illness (

22). We used data from all five cities for all participants who provided valid responses regarding ACEs and written informed consent to the full study. We did not differentiate between the treatment allocation groups. The MINI, HSJSU, and demographic and background information were collected at baseline. Participants completed the ACEs questionnaire at the 18-month follow-up interview.

Data Analysis

To address the first aim of the study, chi-square analysis was used to examine the contribution of ACE category to the risk of criminal justice involvement and victimization in the past six months. To address the second aim of the study, a series of separate logistic regression analyses (

25) was conducted by using cumulative ACEs scores as the predictor variable and criminal justice involvement and victimization as the dependent (outcome) variables, with control for potential confounders (that is, sociodemographic factors, duration of homelessness, and diagnoses of psychiatric disorders). We first examined the bivariate association of each factor with each outcome. Each candidate predictor variable associated with a measure of criminal justice involvement and victimization at p<.10 in bivariate analyses was retained and included in initial multivariate logistic models for criminal justice involvement and victimization outcomes.

Results

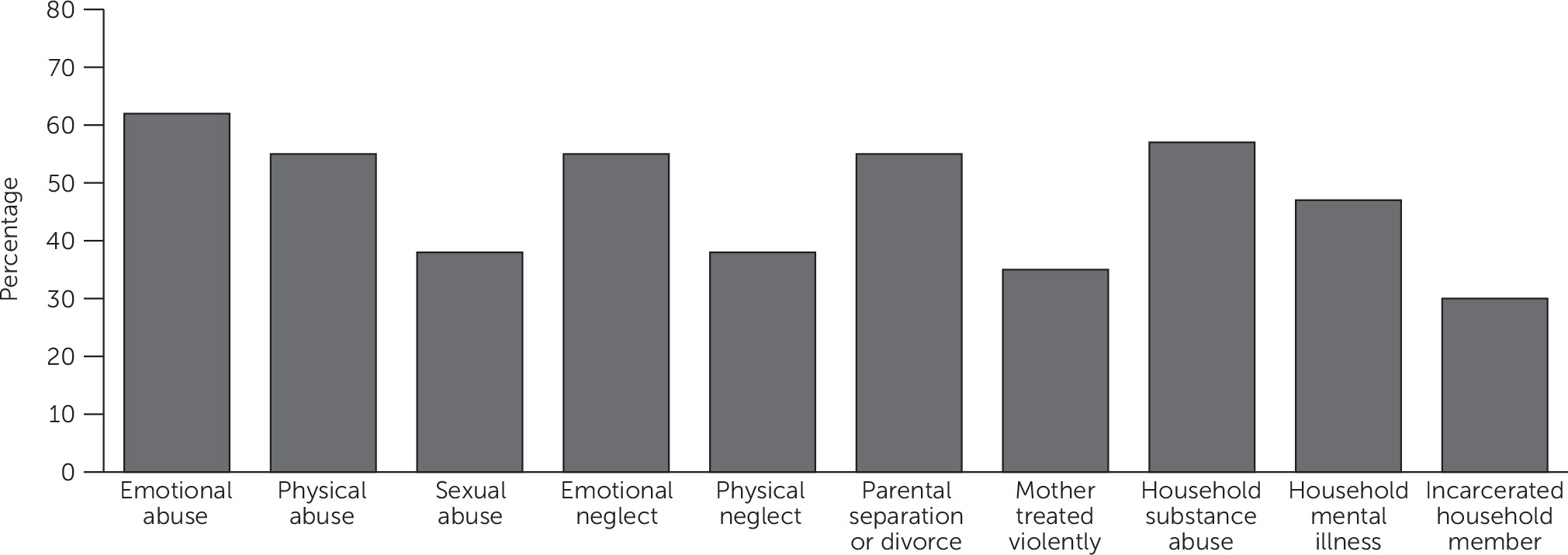

Figure 1 shows the percentage of participants who experienced each type of ACE. Fifty percent (N=938) reported more than four types, 19% (N=365) reported three or four types, 19% (N=353) reported one or two types, and 12% (N=232) reported no ACEs.

Table 1 presents data on the sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric diagnoses of the sample, along with scores on the ACEs questionnaire.

Table 2 presents data on the rates of each type of ACE among participants who reported criminal justice involvement and victimization in the preceding six months. Rates of both criminal justice involvement and victimization were generally higher among participants who had experienced any type of ACE. For victimization, the association was significant for all ten types of ACE; for justice involvement, it was significant for all categories except emotional neglect, sexual abuse, and household mental illness.

Results from logistic regression analyses are reported in

Table 3. The first model, in which cumulative ACEs scores were entered as the only predictor variable, showed the strong impact of the cumulative ACEs score on both outcome variables. In model 2, in which age at enrollment, gender, and ethnicity were entered as covariates, cumulative ACEs score maintained a significant direct relationship with both outcome variables. Being in an older age group significantly reduced the risk of both outcome variables. Being female reduced the likelihood of criminal justice involvement but had no effect on victimization. Aboriginal ethnicity was a significant predictor of an increase in both outcome variables in the past six months.

Adjusting for lifetime homelessness and age at first homelessness (model 3) did not change the relationship between cumulative ACEs and the outcome variables. Being homeless for >36 months was positively associated with victimization but not with criminal justice involvement. Becoming homeless as a youth (under age 25) predicted significantly elevated rates of both outcomes.

Cumulative ACEs continued to be directly related to victimization when the analysis controlled for psychiatric disorders (model 4). However, the relationship between cumulative ACEs and criminal justice involvement was no longer significant in this model. The diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was a strong predictor of victimization. Both alcohol dependence and drug dependence increased the likelihood of both outcome variables.

Discussion

This study investigated the association between ACEs and the risk of criminal justice involvement and victimization over a short period (six months prior to baseline interviews) in a large sample of homeless adults with mental illness. As in previous studies of homelessness (

1), the prevalence of ACEs was very high in our sample, in particular compared with the general population; for example, 50% of our sample experienced more than four types of ACE compared with 12.5% in the general population (

26).

ACEs and Victimization

Consistent with previous studies (

2,

7), our findings indicate that exposure to ACEs increased the risk of victimization among homeless adults with mental illness. Our results regarding the effect of household dysfunction on adult victimization among homeless individuals with mental illness are quite novel. These results are consistent with findings of one of a few studies of homeless mothers and extremely poor housed mothers, which indicated that being exposed to parental fighting, having a mother who was a victim of abuse or battering, having a primary female caretaker with mental health problems, and being placed in foster care increased the risk of exposure to partner violence in adulthood (

27).

Although other factors (for example, earlier homelessness and diagnoses of PTSD and substance dependence) increased the risk of victimization in our sample, a history of ACEs remained a strong predictor of victimization. Individuals with a history of ACEs may develop maladaptive self-attitudes and low self-worth (

28), which can increase the likelihood of engaging in dangerous behaviors (

29,

30), adding to the risk of victimization. Previous studies have shown that individuals with a history of ACEs live in more deprived neighborhoods and have lower levels of educational attainment and lower employment rates, which points to a lack of life opportunities that could act as protective factors against victimization (

31). These findings suggest that among people who share multiple disadvantages associated with mental illness and homelessness, the impact of growing up in a dysfunctional environment and exposure to adversity may further increase the risk of future victimization.

ACEs and Criminal Justice Involvement

Consistent with previous research (

15–

17,

32), results from this study indicate that rates of criminal justice involvement were generally higher among homeless persons who experienced any type of ACE, compared with their counterparts with no such history. However, we did not replicate the findings of studies that showed a significant difference in criminal justice involvement among those with histories of childhood sexual abuse (

16) or emotional neglect (

19,

33).

Of note, the greatest effect on criminal justice involvement was seen among participants who reported parental separation and divorce and an incarcerated household member, compared with those who did not have such experiences. Children of incarcerated parents have a higher risk of antisocial behavior than children without that experience (

34). Living in a home where drug use is present has been shown to increase the risk of severe aggression among runaway and homeless youths (

35). Other studies have similarly indicated that both parental incarceration (

36) and parental separation or divorce (

37) increase the risk of criminality among children and youths. It has been suggested that family disruption is associated with weak parental attachment (

38); emotional problems (

39); and exposure to discrimination, violence, and abuse (

40), which consequently increase the risk of delinquency among the children of these parents.

Results from logistic regression models indicated that exposure to ACEs had a significant effect on criminal justice involvement regardless of sociodemographic factors and duration of homelessness. However, the relationship between ACEs and criminal justice involvement became insignificant when the analysis controlled for the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol and drug dependence. These findings demonstrate that in this population, diagnoses of alcohol and drug dependence may be better predictors of recent criminal justice involvement than a history of ACEs. Prior studies have indicated that substance abuse and dependence are highly prevalent among homeless persons and that these diagnoses are particularly associated with criminal justice involvement (

19,

41). It is not surprising that many homeless individuals may have substance-related offenses or may engage in illegal behaviors to access alcohol and drugs.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, it involved a sample of homeless adults with mental illness, which may limit generalizability of our findings to other groups of homeless individuals. Second, the findings are based on cross-sectional data, self-report questionnaires, retrospective assessment, and single-reporter accounts. Notably, we were not able to present documented cases of ACE or official reports of victimization or criminal justice involvement (for example, a police record), which could increase the reliability of participants’ responses. Because of the highly sensitive nature of reporting ACEs, victimization, and criminal justice involvement, they might have been underreported. The retrospective assessment of variables may also have contributed to misreporting. Third, we did not assess important characteristics of ACEs, such as severity, duration, or age at occurrence, each of which may affect long-term outcomes.

Fourth, the assessment of outcome variables was based on dichotomous variables, which indicated only the absence or presence of victimization or criminal justice involvement during the past six months. Thus we were unable to differentiate more specific aspects and characteristics of any incident. In addition, because the outcome variables focused on events in the past six months, the findings likely underestimate both victimization and criminal justice involvement. Fifth, mechanisms linking ACEs and the two outcome variables need to be determined. Although we accounted for important factors that may have influenced the outcome variables, it is possible that other variables, such as individual factors (for example, antisocial traits and self-worth) or environmental and systemic factors (for example, poverty, access to health and social services, and social inequalities) in childhood or adulthood may also have affected the outcome variables. Finally, many cases of criminal justice involvement among homeless persons are simply a by-product of the visibility of homelessness rather than of having broken any law or regulation. For various reasons, contact with police and negative police encounters are common experiences among homeless individuals (

21,

42). These experiences are particularly common among homeless individuals with mental illness because some police services believe that incarceration of homeless individuals will facilitate access to psychiatric or general medical services (

43). Additional research is needed to extend our findings in other populations of homeless individuals with histories of ACEs.

Conclusions

The findings of this study support efforts to ensure that mental health clinicians and care providers are universally attentive to trauma when providing services to homeless and mentally ill individuals. Because of the long-term impact of ACEs and early homelessness on the development of mental illnesses, homeless adults with histories of ACEs may not particularly benefit from traditional programs and treatment for psychiatric disorders. There is a strong need to implement trauma-informed practices and violence prevention policies (

44) that specifically target homeless adults with mental illness. Intervention efforts should include not only providing housing services but also implementing community-based interventions, treating mental illness and substance use problems, and addressing family and employment problems.

Our findings highlight the importance of early intervention and supports for maltreated children and families at risk of ACEs to reduce the lifelong devastating burden of these experiences on individuals and society. Services for homeless youths should be equipped to adequately address the mental health needs of youths with histories of trauma and adversity, before their vulnerability places them at risk of further harm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the At Home/Chez Soi Project collaborative at both national and local levels, including Jayne Barker, Ph.D., Cameron Keller, Paula N. Goering, R.N., Ph.D., approximately 40 investigators from across Canada and the United States, five site coordinators, numerous service and housing providers, and persons with lived experience of mental illness. Dr. Nicholls is also grateful for her Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator award and foundation grant.