Antidepressants are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat depression symptoms. However, many people without depressive disorders receive antidepressant drugs, commonly referred to as off-label use (

1–

3). Off-label use is often considered to be a type of drug overuse because of insufficient evidence regarding clinical safety and efficacy. It thus indicates poor quality of care and can worsen health outcomes due to adverse drug reactions (

4–

6).

Despite its potential risk, off-label use of antidepressants is prevalent in the United States (

7,

8). It is estimated that between 30% and 70% of all antidepressant prescriptions are for off-label use (

1–

3,

7,

8). Psychiatric symptoms similar to those of depression are shared by other mental disorders (for example, schizophrenia), and this can result in high off-label antidepressant use (

9,

10). Physician specialty and patient insurance status are also important contributors to off-label use: patients visiting primary care physicians are more likely to receive antidepressants off label than those visiting psychiatrists; off-label use is higher among self-paying patients than among those with private coverage (

11,

12). Old age and female gender have been found to be associated with greater off-label use (

3,

13). However, little is known about whether patient race and ethnicity influence off-label antidepressant use.

Previous studies have shown that use of antidepressants is related to patient race and ethnicity (

14,

15). Among patients with similar depression symptoms, those from racial-ethnic minority groups generally have fewer visits to psychiatrists or are less likely than whites to seek providers other than primary care providers for depression treatment (

16). Even with equal access to treatment, the probability of receiving antidepressant therapies was found to be lower among racial-ethnic minority groups than among whites (

14–

17). Racial-ethnic gaps in antidepressant use also differ by insurance types: greater racial-ethnic variation was found among patients covered by private health insurance than among those covered by Medicare and Medicaid (

18).

These findings suggest that off-label antidepressant use may be influenced by patient race-ethnicity and by insurance type. Although health care utilization is generally lower among minority groups than among whites, racial-ethnic minority groups are at greater risk than whites of receiving non–evidence-based pharmacy treatment (

19–

21). This implies that off-label use may be more prevalent among patients from minority groups than among whites. No study has examined whether and how off-label antidepressant use differs by patient race-ethnicity and by insurance type.

To fill this gap, we examined racial-ethnic differences in the use of off-label antidepressants, focusing on the association of such use with type of insurance coverage. We estimated racial-ethnic differences in the likelihood of obtaining off-label antidepressant prescription fills. We compared those racial-ethnic gaps across insurance types by performing the estimation separately for each insurance group.

We also assessed whether the frequency of off-label antidepressant prescription fills differs between whites and racial-ethnic minority groups among those who filled off-label antidepressant prescriptions (“off-label antidepressant users”). A study showed that racial-ethnic disparities in antidepressant use were mainly observed in treatment initiation (

22). Once patients entered the health care system seeking treatment, rates of antidepressant use among blacks and Hispanics were found to be similar to rates among whites. This suggests that among off-label antidepressant users, the total number of off-label antidepressant prescriptions might not differ between racial-ethnic minority groups and whites. However, given that off-label prescription drug use is considered to be inappropriate care, we might observe different patterns in the frequency of off-label antidepressant fills among off-label users and other users. Therefore, we examined the number of off-label antidepressant prescription fills among off-label users by racial and ethnic group.

Methods

Data and Sample

We used multiyear (2000–2010) data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which is a nationally representative annual survey by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of approximately 15,000 households (

23). The survey collects detailed information on health service utilization (type, frequency, and expenditure), insurance coverage, health conditions, and sociodemographic characteristics of respondents and their families. MEPS has an overlapping panel design that collects data over five rounds of interviews during a period of two-and-a-half years. To identify respondents with antidepressant use, we used MEPS Prescribed Medicines files, which report therapeutic classification codes for all prescription drugs filled by respondents.

The study sample included all individuals who filled antidepressant prescriptions at least twice in a given year. This condition was imposed to use the criterion of a minimum of two off-label fills in identifying off-label antidepressant users (see below). Drugs with a classification code of 249 and subclassification code of 76, 208, 209, 250, 306, 307, and 308 are identified as antidepressants from the Prescribed Medicines file. [A list of all antidepressants identified and used in the analysis is included in an online supplement to this article.]

Identifying Off-Label Antidepressant Use

Off-label antidepressant use refers to filling a prescription for an antidepressant without having depression symptoms. MEPS asked respondents to describe their medical conditions, and professional coders recorded those self-reported conditions by

ICD-9-CM diagnosis. We thus identified off-label antidepressant use as having an antidepressant fill without having self-reported depression symptoms (

ICD-9-CM codes 296, 300, 309, or 311) in any round of interviews (

22,

24,

25). [A table in the

online supplement presents data on off-label use rates by therapeutic class and generic names and the medical conditions for which antidepressants were frequently prescribed off label.]

We defined off-label antidepressant users as those filling antidepressant prescriptions for off-label indications at least twice in a given year. This minimum of two off-label fills was used to minimize potential reporting errors. Patients who reported filling off-label antidepressant prescriptions only once may have not accurately recalled their health conditions or the drugs they received. The requirement of two off-label fills allowed us to minimize false identification of off-label antidepressant users.

Outcome Measures

We evaluated two annual outcomes: a binary indicator of off-label antidepressant use (filling off-label antidepressants at least twice) and counts of off-label antidepressant prescription fills among off-label users.

Racial-Ethnic Groups, Insurance Coverage, and Covariates

The key variable in our analysis was respondent race and ethnicity. We constructed three mutually exclusive categories of race-ethnicity: non-Hispanic whites (hereafter referred to as whites), non-Hispanic blacks (referred to as blacks), and Hispanics. We excluded other racial and ethnic groups, which accounted for 3.9% of the sample.

For insurance coverage, we used four mutually exclusive categories: Medicare, Medicaid, private coverage, and uninsured. For individuals with multiple insurance types in a given year, we assigned them to the group with the maximum coverage months. Medicare beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicaid or with private insurance were assigned to the Medicare group because Medicare is the primary payer (

26,

27). The uninsured group included individuals who remained uninsured throughout the entire year. We also identified prescription drug coverage status. Individuals who paid all drug expenditures out-of-pocket were identified as lacking drug insurance; those with any payment from other sources were classified as having drug coverage.

Covariates included age, gender, education, family income, employment status, region, and health condition variables. Education was measured by 0–11 years, 12 years, and ≥13 years of education. Family income was classified as poor (less than 125% of the federal poverty level [FPL]), low (125%−199% FPL), middle (200%−399% FPL), and high (≥400% FPL). Census region (Northeast, Midwest, West, and South) and metropolitan statistical area indicators were also used. Health variables included indicators of chronic conditions (high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, joint pain, arthritis, or asthma), self-reported general medical and mental health status (excellent, very good, and good status versus fair and poor status), and limitations in activities of daily living. Year dummies were included to capture time-specific effects common to all groups.

Statistical Analysis

We began with descriptive analyses to check differences in all study variables across insurance types, using chi-square tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA). We then performed regression analyses that involved two parts. The first part examined off-label use of antidepressants. We used logistic regression to estimate the probability of each respondent’s having off-label antidepressant fills (off-label antidepressant use). With whites as the reference group, we obtained adjusted odds ratios (AORs) of off-label antidepressant use for blacks and Hispanics. We performed the analysis separately for each insurance group.

The second part analyzed the number of off-label antidepressant prescription fills among off-label users (those who had off-label antidepressant fills). We used negative binomial regressions. With whites as the reference group, we computed incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of the number of off-label antidepressant prescriptions of blacks and Hispanics. This analysis was also conducted separately for each insurance group.

To account for the panel designs in the survey (repeated interviews of the same person), we clustered standard errors within an individual. Institutional review board approval was waived because the study used publicly available data.

Results

Table 1 describes the sample characteristics by insurance coverage. After the analysis accounted for oversampling of racial-ethnic minority groups, the proportion of respondents from minority groups was significantly larger in Medicaid (28%), uninsured (17%), and Medicare (13%), compared with private coverage (7%). Off-label use was most prevalent in Medicare (25%) and was least prevalent in Medicaid (18%). Among off-label users, respondents with private coverage had fewer off-label prescription fills (N=6.2) than those in public programs or uninsured respondents (Medicare, N=6.9; Medicaid, N=7.0; uninsured, N=6.3). The chi-square and ANOVA tests indicated that both the prevalence and frequency of off-label use were significantly different across insurance types (p<.001 for both).

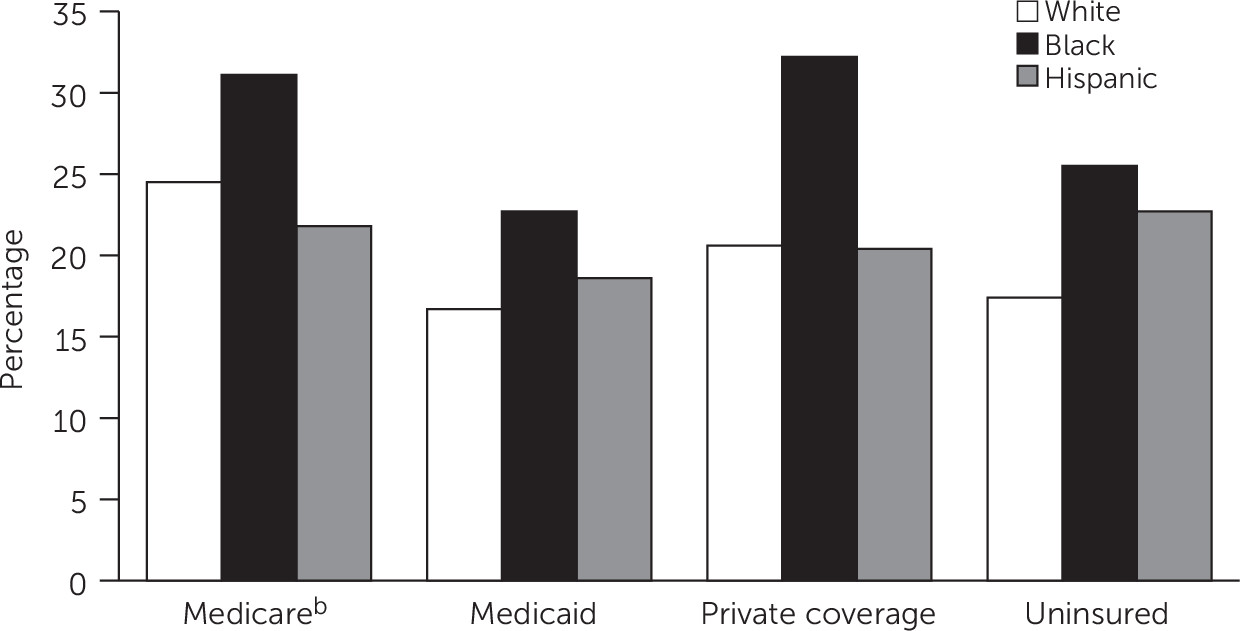

Figure 1 shows off-label antidepressant use rates by race-ethnicity and by insurance type. The off-label use rate was higher among blacks, compared with whites and Hispanics, by 6–12 percentage points across all insurance groups. Rates of off-label antidepressant use were similar for Hispanics and whites in all insurance types except the uninsured group. Chi-square analyses indicated that off-label antidepressant use rates differed significantly across insurance types among whites (p<.001) and blacks (p=.001). Rates among Hispanics did not differ significantly across insurance types.

Table 2 presents results from the logistic regressions of off-label antidepressant use for each insurance group. Blacks were significantly more likely than whites to use antidepressants for off-label indications in all insurance groups (Medicare, AOR=1.68; Medicaid, AOR=1.76; private coverage, AOR=2.10; and uninsured, AOR=1.88). Hispanics had significantly higher rates of off-label use than whites in only the uninsured group (AOR=1.58). The year indicators showed that off-label antidepressant use generally decreased over years in all groups except for Medicaid. Older age was associated with increased off-label use. This may be because older adults tend to visit primary care physicians as a first contact for their health services (

28), and these physicians are more likely than psychiatrists to prescribe antidepressants for off-label indications (

11). Individuals with better self-reported mental health were more likely to have off-label use of antidepressants. A possible reason for this finding is that good mental health among the individuals who reported it may have resulted from their taking off-label antidepressants.

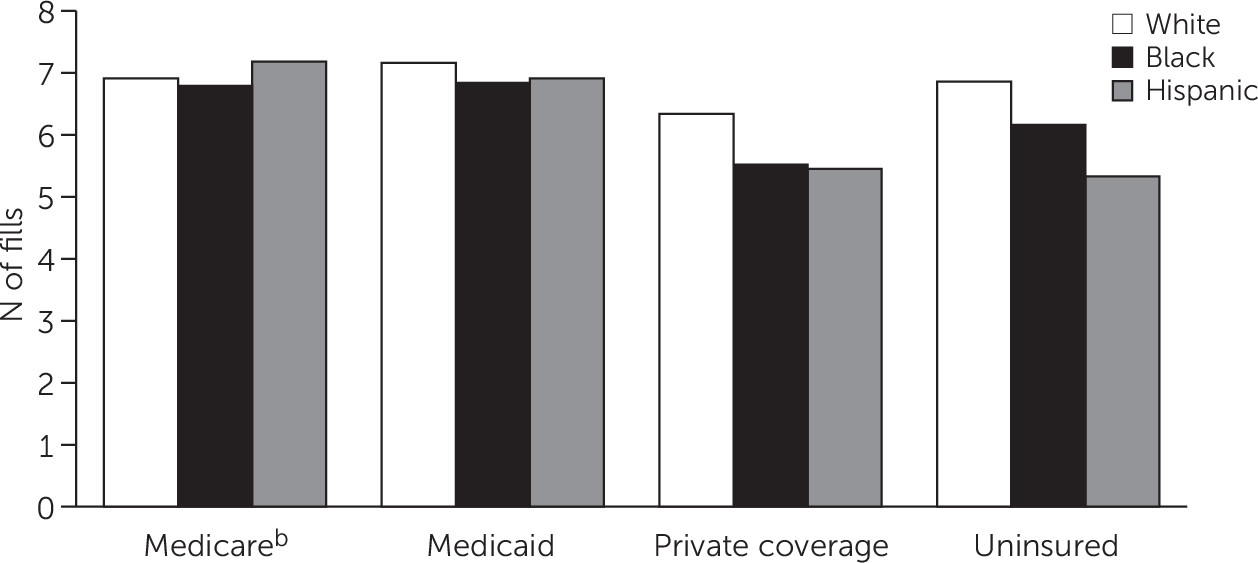

Figure 2 shows the mean number of off-label antidepressant fills among off-label users by insurance group. Whites generally had more off-label antidepressant fills than blacks and Hispanics. The only exception was in Medicare, where Hispanics had more off-label antidepressant fills than whites. ANOVAs indicated that the frequency of off-label use differed significantly across insurance types for all racial groups.

Table 3 shows the results from the negative binomial regressions of the number of off-label antidepressant fills among off-label users. The results showed no significant racial-ethnic differences in Medicaid. In addition, no significant gap was observed between whites and Hispanics in Medicare and between whites and blacks among the uninsured. However, for those with private coverage who initiated off-label use, respondents from racial-ethnic minority groups filled significantly fewer off-label prescriptions than did whites. The incidence rate of off-label antidepressant fills was lower among blacks by 19% (IRR=.81) and among Hispanics by 12% (IRR=.88) compared with whites. Blacks covered by Medicare had fewer off-label antidepressant fills than whites (IRR=.87), and Hispanics without insurance had fewer off-label fills than whites (IRR=.82). These findings indicate that having greater access to off-label antidepressants did not necessarily translate into a greater volume of off-label antidepressant fills.

Discussion

Using data from a survey of a nationally representative sample, we examined racial-ethnic differences in off-label antidepressant use by insurance type. We found significant racial-ethnic gaps between whites and blacks in the likelihood of off-label antidepressant use in all insurance groups. This finding suggests that blacks are exposed to potentially inappropriate care at a higher rate than whites, given that off-label use of medications often lacks scientific support. The finding is consistent with those of previous studies in that persons from racial-ethnic minority groups have been found to be more likely than whites to receive non–evidence-based pharmacy therapies (

19–

21). Off-label drug use can lead to adverse drug reactions, which have adverse effects on health outcomes. Therefore, the white-black differences we found are another indication of disparities in quality of care by race-ethnicity, which raises a public health concern for racial-ethnic minority groups.

The analysis also found that the degree of white-black gaps differed by insurance type: the odds of off-label antidepressant use among blacks were higher than among whites in Medicare (AOR=1.68) and Medicaid (AOR=1.76) and among the uninsured (AOR=1.88) and those with private coverage (AOR=2.10). These racial-ethnic gaps were substantial. The large white-black gaps in public insurance (Medicare and Medicaid) are somewhat surprising. Prior studies showed that racial-ethnic disparities in health service use often do not exist in Medicare or Medicaid because of interventions to eliminate such gaps (for example, provider education and financial support) (

29,

30). Because previous efforts have focused on increasing the level of health care utilization among minority groups, off-label use—potential low quality of care caused by overuse—may not have been considered as an area in which to intervene. However, our finding suggests that attention should be directed to use of non–evidence-based health services, such as off-label prescription drug use, to improve quality of care among racial-ethnic minority groups.

Despite significant white-black differences, we did not find gaps in off-label antidepressant use between whites and Hispanics. This indicates that blacks and Hispanics, although both constituted the racial-ethnic minority population in this study, may have different attitudes and behavioral patterns toward off-label antidepressant use. Our finding suggests that blacks may receive a higher degree of suboptimal care, compared with other racial-ethnic minority groups, at least in off-label antidepressant use. Thus patient education programs specifically focusing on black patients may be needed to encourage them to participate in the shared clinical decision process, which could reduce suboptimal care (

31). Physicians’ understanding of racial-ethnic differences in cultural norms and lifestyles may reduce provider-patient miscommunication and thereby decrease off-label prescriptions (

32).

Our work also provides new information related to the frequency of off-label antidepressant fills among off-label antidepressant users. The number of off-label antidepressant prescription fills among users was relatively small among those with private coverage compared with the publicly insured groups regardless of race and ethnicity. Private insurers may have implemented utilization management tools to reduce off-label antidepressant use. Or public insurance programs may have offered more generous benefit coverage than private insurers for off-label use.

In addition, our analysis indicated significant racial-ethnic variations in the number of off-label antidepressant prescription fills among users. Among those with private coverage, even though whites had a lower probability than blacks of off-label use of antidepressants, once whites initiated off-label treatment, they filled more off-label antidepressant prescriptions than blacks and Hispanics. It may be that persons from racial-ethnic minority groups with private coverage have less generous insurance policies (less favorable for off-label prescription drug use) compared with whites. Whether racial-ethnic minority groups are in private plans with less generous benefits compared with whites is an important factor. However, we could not control for this factor because MEPS does not offer information on plan benefit generosity. As a proxy, we included an indicator of whether a person had drug coverage. However, the results from the analysis without the drug coverage indicator did not change, and we found no significant impact of the drug coverage indicator on off-label antidepressant use in any insurance group. Exploring differences in plan generosity and the association of such differences with off-label antidepressant use by race is an important topic to pursue in future studies.

We found no significant racial-ethnic gaps in the number of off-label antidepressant prescription fills in Medicaid. Compared with private plans and Medicare, Medicaid offers a relatively standardized benefit package to beneficiaries regardless of race and ethnicity. This may explain the smaller racial-ethnic gaps in the number of off-label antidepressant prescription fills in Medicaid compared with other insurance groups.

A few limitations should be noted. First, we used self-reported medical conditions to identify patients with depression because of a lack of claims-based data on diagnoses of depression in MEPS. Self-reports of depression symptoms might not be accurate because of limited memory. However, the self-reported medical information in MEPS is verified by medical providers to ensure the accuracy of the data (

33). Thus reporting errors related to medical conditions in MEPS are likely to be small. In addition, we minimized reporting errors by imposing the criterion of a minimum of two off-label fills to identify off-label users. Second, we did not control for cost-sharing schemes of private insurance plans. We also could not account for drug prescriber characteristics (primary care physicians versus psychiatrists) because of limited data. Finally, we were unable to assess whether cultural differences between whites and racial-ethnic minority groups, such as stigma related to a diagnosis of a mental illness, affected off-label antidepressant use because of limited data. This is an important topic to pursue in future research. Despite these limitations, our study is the first to document large differences in off-label antidepressant use among persons with private insurance in a direction unfavorable to racial-ethnic minority groups. Continuing assessment of this issue is needed to improve quality of care for all racial-ethnic groups.

Conclusions

In all insurance groups, blacks were more likely than whites to use off-label antidepressants. However, after whites began off-label use of antidepressants, they tended to fill a greater number of off-label antidepressant prescriptions than blacks or Hispanics. Considering that off-label use may be inappropriate, clinical and policy efforts should aim to reduce off-label antidepressant use, with particular attention to racial-ethnic differences.