Internationally there has been a growing emphasis on the provision of timely early intervention for mental disorders among young people. The vast majority of adult-pattern, major mental disorders have their onset during the developmental period between the ages of 12 and 25 (

1). The incidence and prevalence of mental disorders in this age group is high (

2), and mental disorders are associated with significant social and economic disability among young people (

3). However, members of this age group also have relatively low rates of help seeking (

4).

These factors have led to the introduction of several new models of health care provision that focus on greater engagement of young people with emerging, but often subsyndromal forms of mental disorder (

5). In Australia, publicly funded youth mental health centers known as “headspace” (

6) have been specifically designed to intervene early in the development of psychiatric symptoms. The goal of headspace is to provide holistic care, reduce secondary morbidity, and prevent or delay the onset of severe mental disorders and their associated adverse consequences. These centers provide easy-access, primary care–level services from a mix of professionals to address needs associated with mental health, general medical health, alcohol and other drug use, and education and employment support.

A focus on early intervention has also drawn attention to the need to develop a greater understanding of illness trajectories and how and when to intervene with youths presenting with a range of symptoms, impairments, or distress. Clinical staging models, adapted from those used routinely in general medicine (for example, in cardiovascular disease or cancer), have been proposed as a way for providers of youth mental health services to identify youths who are at highest risk of developing severe mental disorders and persistent disability (

7). These models are especially helpful for classifying the clinical presentations of individuals seen in youth mental health services operating at the interface of primary and secondary care (

8,

9). In one such transdiagnostic staging model, outlined in

Table 1, individuals are placed on a continuum, from help seeking for mild symptoms (stage 1a) to attenuated features of a severe disorder (stage 1b), discrete severe mood and psychotic syndromes that meet traditional diagnostic thresholds for a disorder (stage 2), recurrent illness (stage 3), or end-stage, unremitting (stage 4) illness (

7,

10,

11). Inherent in the model is the concept that within each stage, individuals are at differential risk of progression to the next, more severe clinical stage over time. In an earlier longitudinal study, we demonstrated that approximately 19% of a transdiagnostic sample who met criteria for stage 1b at initial presentation progressed to stage 2 (met criteria for a major mental disorder) within 12 months (

11). Preventing or delaying progression to stage 2, particularly among the groups at highest risk of early transition (stage 1b), is an important and measurable goal of youth services that are based on clinical staging models. The effectiveness of services can be tested by their relative capacity to reduce or delay clinical or functional deterioration among those identified as being at high risk of disease progression.

There is much variability in rates of individual patient treatment response to real-world clinical services, including deterioration, persistent but stable levels of problems, and clinically or statistically significant improvement. Additionally, there is discordance between the outcomes of efficacy trials of homogeneous, selected subpopulations and naturalistic studies, with the latter often reporting much poorer outcomes (

12). For example, Warren and colleagues (

13) showed that 24% of young people treated in a public community mental health service in the United States demonstrated statistically reliable deterioration in clinical outcomes over approximately six months, whereas 28% showed reliable improvement. Murphy and colleagues (

14) reported a reliable deterioration rate of 16% over three months among patients in an outpatient child and adolescent psychiatry clinic.

To date, there have been two published studies reporting on the clinical and functional outcomes among young people attending services at headspace. The first was a short-term study of a large national sample of close to 10,000 young people (

15). The study reported change in outcomes between first and last service visits (the mean duration of treatment was not reported), which varied between patients. Using statistically reliable improvement analysis (

16) of measures of psychological distress (

17) and social and occupational functioning (

18), the study found that reliable improvement in psychological distress was demonstrated in 26% of patients and reliable improvement in social-occupational functioning was demonstrated in 31% of patients. Additionally, 8% and 16% of patients showed reliable deterioration in distress and functioning, respectively. However, no analysis of differences between severity-based subgroups was conducted (

8).

The second study was conducted in a single headspace center and reported on the differential outcomes of 880 young persons by clinical stage (

19). It showed that individuals with conditions characterized as stage 1b demonstrated the same degree of improvement between baseline and last (repeated) measurement on both the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) compared with individuals with less severe conditions (stage 1a). However, given that individuals with conditions characterized as stage 1b typically began treatment with greater levels of distress and impairment, their final clinical outcomes over the same period were significantly poorer than individuals who began treatment at stage 1a. On the basis of this and related findings in this group (

8,

9,

11,

19,

20), we developed a model of care that gave particular clinical attention within these settings to persons with clinical presentations characterized as stage 1b (

21).

This study reports on the characteristics of patients with subsyndromal conditions characterized as stage 1b. It also reports on the longitudinal clinical and functional outcomes for these young people (as a group and as individuals) over a period of six months.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

With ethics approval granted by The University of Sydney Human Ethics Board, we obtained written informed consent from patients (or their guardians for those under age 18) to collect and use their deidentified data. Participants were ages 12 to 25, had conditions that met criteria for clinical stage 1b according to our published criteria (

11) (

Table 1), and attended headspace Campbelltown between January 2014 and June 2015. The Campbelltown facility is a youth mental health service located in outer metropolitan Sydney, Australia, that provides early intervention treatment. There were no differences in the care or treatment provided to youths who did or did not give informed consent to participate in the study.

As a specialized, primary-level service for young people, headspace provides services such as care coordination and support by allied health professionals; general medical services by general practitioners (primary care physicians); more specialized mental health services delivered by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists; and education, employment, and other social supports delivered by colocated specialist services. A key aspect of headspace services is the direct connection and ease of access to secondary-level specialist services, such as early psychosis services (

5). The specific clinical model employed in this study involves a comprehensive mental health assessment by a senior psychologist or psychiatrist followed by consensus-based stage allocation by the assessing clinician and the multidisciplinary team. Interventions are matched to that stage, and outcomes are subject to routine monitoring by a multidisciplinary team. The results of monitoring guide reassessment of stage and, if indicated, alteration of the treatment plan. The clinical model has been previously described (

21).

Data Collection

Demographic details (age and sex) and a subjective estimate of the age of onset of first disabling symptoms or psychological problems were collected by treating clinicians at service entry (baseline). At baseline, three months, and six months, clinicians also collected data on psychological distress (K10) (

17), symptoms (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale–Expanded [BPRS]) (

22), and social and occupational functioning (SOFAS) (

18); consensus-rated clinical stage (obtained from clinical team meetings); and the total number of sessions with a psychiatrist or psychologist attended by the patient. Possible scores on the K10 range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating a greater range and severity of psychological symptoms. Possible scores on the BPRS range from 0 to 168, with higher scores indicating a greater range and severity of clinician-rated psychiatric symptoms. Possible scores on the SOFAS range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better social and occupational functioning.

Statistical Analyses

Analysis was performed by using SPSS, version 22.0, with statistical significance set at p<.05 (two-tailed) for all analyses. Outcomes were measured by using both effect size (ES) change and statistically reliable change. ES change was calculated in standardized units of change between the mean scores at baseline and at later time points, with the baseline standard deviation (SD) for the relevant measure used for standardization. Statistically reliable change was calculated by using the reliable change index (RCI) according to the methods set out by Jacobson and Truax (

16). The methods compare the change between an individual's scores at service entry and later time points (in this case three and six months into treatment) with the standard error of measurement of the scale. The RCI, therefore, represents the smallest amount of change that is unlikely to be caused by statistical fluctuation or chance. Whereas other methods identify treatment differences between groups, RCI identifies treatment outcomes within individuals.

Outcomes are reported as means and SDs or as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), depending on the normality of distributions of the measure or subscale. We used an RCI of 7 points for the K10 and 10 points for the SOFAS (

15). Because of a lack of normative data reported for the BPRS in this age group, we used the Jacobson and Truax method (

16) to calculate an RCI for the BPRS on the basis of mean±SD scores for a control group reported by Hermens et al. (

20), producing an RCI of 11 points.

Stepwise linear regression was used to examine the associations between clinical, social, and demographic variables at baseline and treatment intensity (number of psychiatry, psychology, or combined sessions) with final outcome scores.

Results

Of the 1,142 patients who attended the service during this time, 867 provided consent for their deidentified information to be used for research purposes. The eligible stage 1b sample comprised 243 patients with a mean±SD age of 18.1±3.0 years; 36% (N=87) were male. The remainder of the sample was not eligible for the study because their clinical presentation was not staged at 1b, with 529 (61%) rated as stage 1a and 95 (11%) rated as stage 2 or above. The mean age of onset of first disabling symptoms or psychological problems was 13.0±3.1 years, according to subjective estimates. Most (N=232, 95%) individuals attended sessions with both a psychiatrist or a psychologist over the six-month period, and the average number of sessions attended was 13.9±11.8. Those who consulted a psychologist only (N=240, 99%) or a psychiatrist only (N=233, 96%) attended 10.0±6.3 and 6.0±4.3 sessions, respectively.

Group-Level Change in Outcome Measures

Baseline scores for the SOFAS, K10, and BPRS were 61.1±8.8, 31.1±8.9, and 40.6±8.3, respectively.

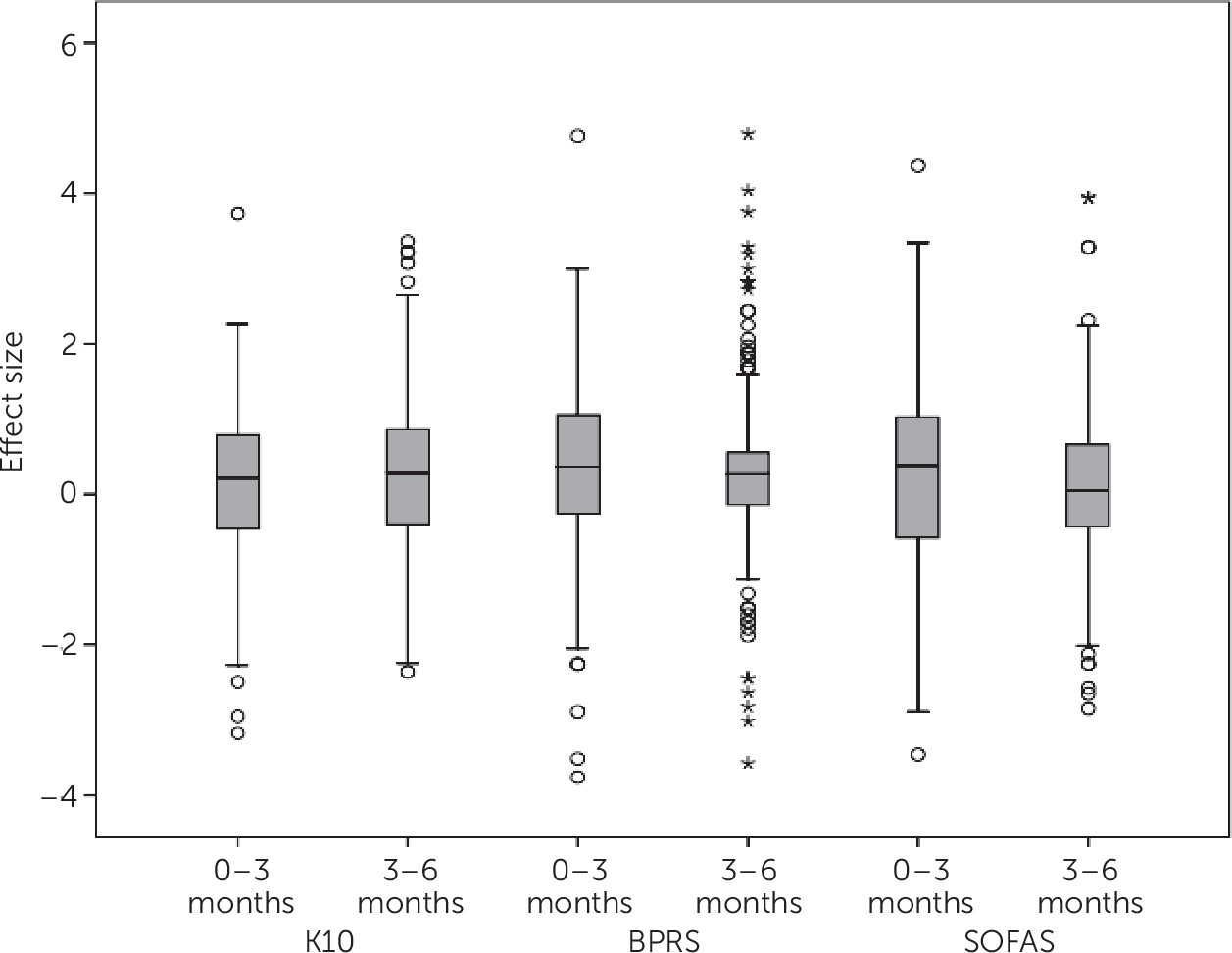

Table 2 and

Figure 1 show that by six months, median ESs of .25, .46, and .56 were observed for functioning (SOFAS), symptoms (BPRS), and distress (K10), respectively. ESs for functioning and symptoms were slightly lower in the three- to six-month period compared with the zero- to three-month period. The sample was divided into quarters based on ES change at each time point. The degree of improvement for the top 25% of the sample was much higher than the degree of deterioration for the bottom 25% of the sample, with ESs exceeding 1.0 for functioning and symptoms and approaching 1.0 for distress.

Individual-Level Change in Outcome Measures

In terms of reliable change in scores on the K10, SOFAS, and BPRS, respectively, between baseline and six months,

Table 3 shows that 13%, 9%, and 5%, of the sample deteriorated, 54%, 66%, and 72% showed no reliable change, and 33%, 25%, and 23% had scores indicating reliable improvement. The degree of change for individuals across and within each of the time periods for each measure varied. More patients exhibited reliable deterioration across all measures in the first three-month period than in the second three-month period, whereas more patients exhibited reliable improvement on the BPRS and SOFAS in the first three-month period than in the second three-month period (data not shown).

Of the 21 patients who deteriorated on the SOFAS over six months, none had deteriorated at both the zero- to three-month and the three- to six-month periods. Eight of the 21 (38%) patients who showed overall deterioration by six months showed no reliable change at both the zero- to three-month and the three- to six-month periods. Forty-nine percent (N=79) of those who showed no change in the SOFAS at six months had scores reflecting either deterioration or improvement at one or both of the three-month measurement points. Thirty-five (57%) of those who improved in the SOFAS at six months improved reliably in the first three months.

The BPRS showed much less movement across change categories over time than the other measures, with 63% of patients showing no reliable change at all measurement points (0–3, 3–6, and 0–6 months). Sixty-six percent (66%) of those who improved at six months showed reliable improvement in the first three months.

On the K10, 25% of the sample who showed no change at six months either improved or deteriorated in the first three months, then experienced the opposite outcome (improved to deteriorated or deteriorated to improved) in the second three months. Fifty-eight percent and 54% of patients who deteriorated or improved (respectively) did so in the first three months.

Predicting Six-Month Scores

After the analyses were controlled for demographic and baseline symptoms and functioning, stepwise regression demonstrated that about 17% of the variance in K10 score (R=.421, adjusted R2=.170, F=25.60, df=2 and 238, p≤.001) and about 4% of the variance in BPRS score (R=.231, adjusted R2=.041, F=4.46, df=3 and 237, p=.005) were accounted for by number of sessions with a psychiatrist. [Details of final regression models and other significant covariates are available as an online supplement to this article.] Also, after the analyses were controlled for other factors, stepwise regression demonstrated that about 8% of the variance in SOFAS score at six months was predicted by total number of sessions with a psychiatrist and psychologist (R=.301, adjusted R2=.083, F=11.82, df=2 and 238, p≤.001).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that on average, young people who accessed an early intervention service for treatment of subthreshold manifestations of severe mental disorders and concurrent functional impairment showed varied symptomatic and functional outcomes over a six-month period. Although rates of reliable improvement were modest, they appear to be comparable with those reported in other studies of youth cohorts (

13,

15). However, rates of deterioration among patients in this study appear to be slightly lower than reported in other studies of youth cohorts. An important objective of early intervention services is to prevent worsening or deterioration, especially among those at greatest risk of progression to poorer functional or clinical outcomes or progression to full-threshold severe disorders. Whereas aiming for reliable improvement over time for patients is the most desirable goal, halting deterioration among those deemed to be at highest risk of deterioration is also a desirable goal. With this in mind, the finding that most of these at-risk patients experienced no reliable deterioration in distress, functioning, and symptoms over the six-month period can also be viewed as a worthy outcome. Longer-term tracking of these patients will help to determine if rates of reliable improvement rise with more time spent in treatment.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the use of the RCI is recognized as being extremely conservative when it comes to measuring treatment outcome (

23). Those categorized as having improved demonstrate unequivocal improvement, whereas those categorized as having experienced no change will include a mix of minimal improvers, minimal deteriorators, and patients who did not respond to treatment over the defined time period. For example, a variation of less than 10 points in either direction on the SOFAS (a range of 20 points) will still result in an allocation to the “no change” category. Future research, especially in other highly variable at-risk cohorts, could report on this greater range of individual outcome classifications over a longer period (

23).

Direct comparison with findings from other research is not possible because of variability in patient (demographic information and clinical severity) and service-level characteristics across studies. The rates of deterioration at six months for this high-risk cohort on functioning (9%), distress (13%), and symptoms (5%) appear to be relatively lower than or equivalent to those reported elsewhere. On the basis of our own prior naturalistic follow-up of stage 1b patients who had received treatment as usual (

11), however, we expected to see rates of clinical deterioration in this subgroup on the order of 20%. Although not directly examined in this study, it is possible that in addition to the interventions provided, the routine monitoring aspect of the service model may have contributed to these comparatively lower deterioration rates.

The value of routine outcome measurement (ROM) in these settings has been proposed previously and has been directly linked to improvements in patient outcomes of modest effect size (

24,

25). If some young people do, in fact, present to care with pretreatment negative illness trajectories, as is predicted by staging models, then proactive and objective monitoring of outcome is vital. This study showed that degrees of improvement or deterioration vary considerably between individuals, across and within different periods, and across various measures. As such, this study lends some support to using clinical models with embedded systematic ROM practices for individual patients. Such models have the capacity to be more responsive to changes within the individual, resulting in a more personalized approach to care.

There is some evidence that treatment intensity is related to clinical improvement among youths (

15), although other studies have found no relationship between outcome and number of sessions (

26). We found that a small amount of the variance in outcome was explained by treatment intensity (primarily a greater number of sessions with a psychiatrist or (for variance in functioning) with a psychiatrist and a psychologist). However, the findings from this low-resource study do not allow us to further clarify any associations between improvement and treatment intensity, given that intensity was crudely measured. Also, it is possible that the service model, the range and quality of interventions provided (such as medication or therapist adherence to cognitive-behavior therapy models), the physical environment, the therapeutic relationship, the coordination of care needs, and other factors had additional unmeasured effects on outcome. In line with previous findings, baseline severity and early symptomatic or functional change appear to be most strongly linked with later outcomes (

12).

The lack of real-world outcome data regarding early intervention services makes the current observational study both timely and important. However, because the study had several limitations, it should be considered a starting point for further research. For example, the study featured a quasi-experimental design with a lack of a control or a comparison group. Instead, a prospective observational monitoring approach was employed, and both patient and clinician ratings of outcome were collated across a heterogeneous clinical sample. This approach is in contrast with a randomized controlled trial, which would have involved recruiting a more selected, homogeneous sample. Although our goal was to enhance generalizability of the findings, it is notable that we cannot be certain of how much the observed outcomes vary from naturalistic patterns of disease or illness progression that might have been observed in an untreated population. Also, some of the analyses demonstrated that the observed outcomes were not normally distributed. The sample size limited the extent to which this distribution could be examined, and either a larger cohort or longer follow-up period may be needed to determine the importance of this limitation. Treatment data were also limited to those that could be reliably collated via routine clinical practice, namely number of treatment sessions, rather than the type or quality of the intervention. Although number of treatment sessions has been used as a proxy measure of the intervention received, a more systematic assessment that includes markers of quality assurance is likely to shed more light on any associations between treatment (including use of medication) and outcomes.

Conclusions

Given that many nations are moving to develop and expand the early intervention services provided to youths with emerging mental disorders, this study provides an example of incorporating a stage-based service framework into clinical settings. A guiding principle of this approach is that resources are allocated according to individual needs (severity of symptoms and level of functional impairment) regardless of whether the patient’s condition meets subthreshold or threshold criteria for a major mental disorder. This approach, which is a foundation of general medicine, is relatively untested in mental health, but this study identifies both the potential importance and the difficulties of undertaking such research.