Self-direction involves control by participants with serious mental health conditions of a portion of funds typically spent on their mental health treatment. Self-directing participants allocate individual budgets in a manner of their choosing within a set of program parameters, selecting and purchasing goods and services to work toward their goals. Typically, a coach or broker supports participants, facilitating development of person-centered plans, helping track progress toward goals and objectives, and assisting participants with financial management (

1–

3). Self-direction purchases are broad ranging and may include clinical services and nontraditional expenditures, such as transportation, vision and dental care, and computers (

1,

4). Self-direction arrangements take different forms and are housed in and overseen by various entities, including mental health authorities, managed care entities, social service agencies, and advocacy organizations (

5). At last count, approximately 700 individuals with serious mental health conditions participate in self-directed services in the United States (

5), and mental health self-direction is expanding worldwide (

6).

A 2014 systematic review examining 15 studies, including four conducted in the United States, concluded that although mental health self-direction is associated with increased quality of life and cost-effectiveness, extant research had significant methodological limitations. The authors called for more rigorous research to inform policy and practice (

7). Since that review, Spaulding-Givens and Lacasse (

2) published a descriptive study of Florida Self-Directed Care (FloridaSDC). In that study, participants had modest improvements in mental health–related functioning and spent a majority of days in the community as opposed to institutional settings. A recent qualitative study documented gains by self-directing participants in several domains, including vocational pursuits, independent housing, and community inclusion (

1). Another study explored purchase types and concluded that self-direction enabled individuals to better address their needs through individualized strategies that support wellness and increase engagement in meaningful activities (

4).

This study adds to this evidence base. Its purpose was to compare two functional outcomes, employment and independent housing, between individuals who did and did not participate in mental health self-direction. These domains reflect self-direction’s value base, which is rooted in principles of recovery, independence, and community inclusion. A recent Institute of Medicine report highlighted similar indicators as key social determinants of health (

8), and both were identified as priority outcomes in the report of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (

9) and in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s

Description of a Good and Modern Addictions and Mental Health Service System (

10). Service users, families, and administrators alike value these outcomes, which enhance quality of life and community inclusion and may reduce reliance on publicly funded systems. Using a quasi-experimental design with coarsened exact matching (

11) and logistic regression, we estimated odds of change or maintenance of a positive outcome in employment and in housing independence among individuals who were and were not self-directing.

This study used data from FloridaSDC, the country’s oldest and largest mental health self-direction effort. There are two FloridaSDC programs in the state, which contracts mental health services through regional systems of care overseen by nonprofit managing entities. These voluntary programs enroll approximately 330 individuals and are funded through a combination of state and local funds. To be eligible for either FloridaSDC site, individuals must be at least 18 years old and designated as having a serious and persistent mental illness as determined by the state. Individuals must also have permanent residence in the program areas and rely on public funds to cover mental health services. If individuals are not enrolled in Supplemental Security Income, Social Security Disability Income, or veterans’ benefits, they must be in the process of applying for those benefits. FloridaSDC participants must be legally competent to make financial decisions and may not be enrolled in assertive community treatment. During the study period, SDC participants enrolled in public benefits received a yearly budget of approximately $1,900 per year, which could be used in addition to their existing insurance coverage. Uninsured individuals received an approximately $3,700 yearly budget, with half reserved for outpatient mental health treatment, such as psychiatric treatment and therapy. With support from a coach and within program policy guidelines, participants link purchases to specific recovery goals in their person-centered plans.

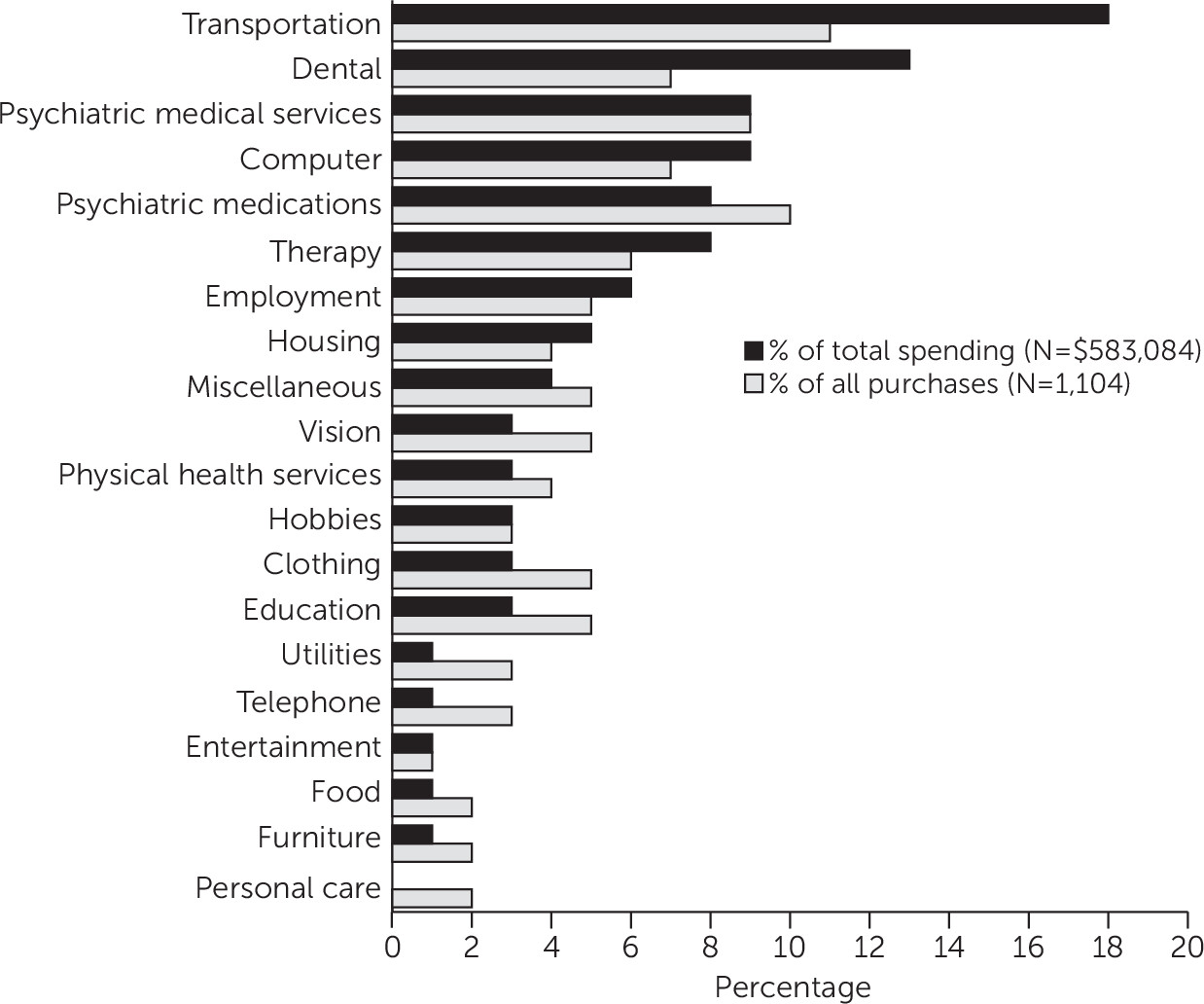

Figure 1 depicts a breakdown of FloridaSDC spending by purchase category at one site (where such data were available). Most purchases were related to goods and services other than mental health treatment (some participants accessed mental health treatment by using Medicaid or other benefits, and these services are not included in

Figure 1), from transportation and dentistry to housing and employment-related supports.

Methods

The Brandeis University Institutional Review Board and the Florida Department of Children and Families’ human protections administrator reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Data and Variables

Data were obtained as limited, deidentified data sets from the two managing entities that oversee the FloridaSDC programs, with consent from the state. According to state regulations, managing entities must collect demographic information, service event data, and mental health outcomes data. Providers report demographic information to managing entities at admission and whenever that information changes, and mental health outcome assessments are reported at first assessment, quarterly thereafter, and at discharge.

The data sets included demographic and outcomes information for all adults with a serious and persistent mental illness designation. Information regarding self-direction budget purchases and service use details were unavailable for both programs; therefore, this information was not analyzed in this study. The data sets used in the study covered different periods because the managing entities assumed responsibility at different times and transferred the data at different times. The program A study period spanned 4.8 years, beginning July 1, 2010. The study period for program B covered three years, beginning July 1, 2012. Because of these disparate periods and because of demographic differences, the data sets were kept separate during the selection of matched comparison cases, and results are reported by site as well as in the aggregate.

Individuals enrolled in FloridaSDC were categorized as the intervention group, and individuals who never enrolled in FloridaSDC were categorized as the comparison group. Before data cleaning, the data set included 21,183 individuals, 403 of whom were SDC participants. Comparison group individuals who did not meet FloridaSDC eligibility criteria at any point during the study period (under age 18, enrolled in Florida assertive community treatment, or resided outside the geographic service area) were removed, as were individuals with only one assessment. After data cleaning and before matching, there were 403 FloridaSDC participants and 12,209 nonparticipants.

We created two binary dependent variables—employment and independent housing—by comparing measurements at first and last assessment for each individual. Outcome variables, selected on the basis of study aims, were constructed to capture both positive change and maintenance of a positive outcome over the study period. There were three available indicators for exploring employment: employment status, income from paid employment (past 30 days), and days worked for pay (past 30 days). We selected days worked for pay because it reflects work behavior (as opposed to income) most accurately and in greatest detail. Individuals with a positive employment outcome were those who either increased the number of days worked in the past 30 days at last assessment compared with first assessment or reported 20 or more days of work at both assessments. For housing independence, we constructed an outcome variable indicating transition from dependent housing (dependent living with others, group home, assisted living, supported housing, or hospital) or homelessness to living independently or maintenance of independent housing status at first and last assessments.

We defined a positive program effect as either a positive change or maintenance of an already good outcome to account for the dual purposes of FloridaSDC—that is, helping participants gain access to employment and independent living, as well as preventing them from losing the resources they already have. The preventive goal is important to capture because the target population is at continued risk of losing access to employment or independent living. Focusing only on participants who lacked access to these resources at first assessment would miss the effects of the program in preventing loss of resources. For example, if SDC participants are more likely than non-SDC participants to remain living independently from first to last assessments, this positive outcome would not be evident from examining changes in independent living status over time.

Matching and Analysis

We used coarsened exact matching to create a non-SDC comparison group (

11,

12). This straightforward method is designed to reduce imbalances between groups by using specified categorical variables. The matching algorithm (available as an SPSS add-on) constructs a stratum for each combination of covariates and matches each intervention participant to one or more nonintervention individuals sharing the same stratum. The algorithm then produces weights to account for postmatch group size differences (

13). This method was chosen over other matching methods (for example, propensity scores) because of the high number of categorical variables in the data set and because it results in matched cases that share identical values (

12).

Factors hypothesized to affect both the outcomes and participation in FloridaSDC were selected as matching variables (

14). Variable choice was informed by reviewing prematch descriptive statistics, key informant interviews with individuals knowledgeable about self-direction, and information gleaned from previous FloridaSDC evaluations (

1,

2,

5,

15–

17). We selected the following matching variables: age, high school completion, gender, ethnicity (program A), race (program B), schizophrenia diagnosis, substance use disorder diagnosis, marital status, county of residence, veteran status, limited English proficiency, arrests (ever arrested during the study period), activities of daily living (ever assessed as unable to perform activities of daily living during the study period), community tenure (ever spent one or more days out of the community during the study period), days between first and last assessments, and disability income receipt. We successfully matched 67% (N=271) of the SDC participants to 1,099 non-SDC participants. Postmatch weights were used in all subsequent analyses.

We fitted two logistic regression models to estimate the likelihood of achieving a positive outcome on each of the dependent variables, controlling for relevant covariates. Model specifications were guided by a priori theory and methodological considerations. To control for differences in outcome variables at the first assessment, we included the value of the outcome measure at the first assessment as a covariate in each model. The set of standard covariates was age, gender, race, ethnicity, high school completion, county of residence, program site, veteran status, marital status, physical disability, schizophrenia diagnosis, substance use disorder diagnosis, disability income receipt, days between first and last assessment, value of the outcome measure at first assessment, and any of the following during the study period: arrested, unable to perform activities of daily living, admitted to services as incompetent or involuntary, and spent one or more days out of the community.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the SDC and non-SDC groups before and after matching are presented in

Table 1. Before matching, the groups were significantly different on nearly all measures. After matching, there were no statistically significant differences between the SDC and non-SDC groups.

Table 2 presents unadjusted mean values of outcome variables at first and last assessment for SDC and non-SDC groups. The mean differences depicted in

Table 2 do not capture maintaining a desirable outcome over the study period. To capture maintenance in addition to positive gains, we used the outcome variables described above rather than differences in means or proportions with improved outcomes for the multivariate analysis. Notably, SDC participants’ first assessments did not constitute a true baseline because 58% (N=158) of the SDC group were enrolled in FloridaSDC prior to the beginning of the study period. Some of the observed first-assessment differences may be due to having received FloridaSDC prior to the first observation. The regression models adjusted for this nonequivalence by estimating odds ratios (ORs) while controlling for the first-assessment values of outcome measures.

We used logistic regression to produce adjusted ORs of SDC membership predicting the likelihood of a positive outcome, controlling for observed first-assessment nonequivalences (

Table 3). The logistic regression results indicated that, when covariates were held constant, SDC participants in both programs were significantly more likely than the non-SDC group to experience a positive outcome in days worked for pay (OR=1.73, p≤.01). SDC participants had more than twice the odds (OR=2.04, p<.05) of maintaining or attaining independent housing, compared with the non-SDC group, when the analysis controlled for covariates. We calculated two indicators of effect size: Cohen’s h and number needed to treat (NNT). Cohen’s h was .18 for employment and .21 for independent living. To achieve a positive employment outcome for one participant, 18 participants need to be enrolled in SDC for three years (the sample mean for length of enrollment). The corresponding NNT for a positive independent living outcome was 16 participants. As discussed above, these numbers reflect both improvements and maintenance of positive outcomes and were adjusted for all model covariates, including outcome values at first assessment. They indicate small effect sizes, with a larger effect size on independent living than on employment.

Discussion

Using several years of administrative data, we found evidence suggesting positive effects of self-direction on both outcomes of interest: employment and independent housing. Although these results are promising, findings should be regarded with caution because of study limitations. Although matching eliminated all observed differences between SDC and comparison groups, unobserved group differences likely remained. As is typical of quasi-experimental designs, matching and statistical controls minimized but did not guarantee the elimination of case mix issues, so the results should be regarded as preliminary. Furthermore, only 67% of SDC participants were successfully matched, and approximately one-third of SDC participants were thus not included in the analyses. However, in preliminary analyses we used only 10 variables to define the matching algorithm (versus the 16 variables in the final analysis); while approximately 90% of the sample was successfully matched, the balancing between the groups was inadequate. Therefore, we chose to sacrifice the number of matches for quality of matches, and the overall results were robust to these varying specifications. Future studies should collect more detailed background information in order to account for a broader range of potential nonequivalence factors. However, it is worth noting that complete intergroup equivalence is notoriously hard to establish in studies of socially complex outcomes, even with randomized controlled designs (

18).

Second, participants’ first assessments did not constitute a true baseline because a majority of the FloridaSDC group were enrolled prior to the beginning of the study period. Reported group differences in outcomes between first and last assessments are net of first-assessment differences, possibly masking some intervention effects that might occur before first assessment. More accurate estimates of intervention effects would have been possible with a design utilizing true baseline data.

To assess the degree to which the lack of a true baseline affected our results, we repeated the analysis limiting the SDC group to the 158 participants who enrolled during the study period and thus had a true baseline. For all models, the results were in a direction similar to that in the full sample. SDC enrollment remained a statistically significant predictor of the employment outcome in the combined sample (OR=2.22, p<.01), whereas its effect on independent living did not reach significance (OR=1.87, p=.165). The difference in significance level is to be expected given the reduction in sample size, and the sensitivity analysis suggested that the program effects reported above were not unduly biased by the lack of a true baseline.

Because the study was limited to available administrative data, potential confounders—including information about SDC-purchased goods and services and implementation-related factors, such as informal screening practices—were not available in the data. Furthermore, the data were collected by providers for billing and reporting purposes and are thus subject to possible unmeasured biases. Although it would have been desirable to investigate self-direction’s relationship to service use, detailed service use information was not available.

Despite its limitations, this study had unique and important strengths. The outcomes have import for publicly funded mental health systems, and possible improvement in the areas of employment and independent housing suggests that persons are enhancing their independence and self-sufficiency. These findings are supported by a recent qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews with 30 FloridaSDC participants (

1). In that study, 10 interviewees reported gains in employment, five reported recent or planned transitions to independent housing, and nearly all reported pursuing valued roles in their communities. This study’s quantitative findings, from a sample that included nearly all eligible FloridaSDC participants, provides initial confirmatory evidence of findings reported for the smaller sample.

To the best of our knowledge, this study had the longest observation period of any mental health self-direction research. Self-direction is a complex intervention and requires a high level of participant engagement (

1). Developing person-centered plans and working with a budget takes time. As such, gains may not be fully realized until after months or years of participation. This study’s three-to-five-year observation period may provide a more representative picture of program effects compared with earlier studies.

Conclusions

This study adds to a small but growing body of literature addressing mental health self-direction’s effects. Compared with nonparticipants, self-directing participants were more likely to improve, or maintain at high levels, engagement in paid work and independent housing. We note, however, that there were marked case mix differences between groups, and there was uncertainty about whether the analytic approach adequately accounted for these differences. Future research should seek to corroborate these findings using more robust methods and might involve additional outcome domains, such as service use and social connectedness, as well as alternative measures for employment, community integration, and independent living. Future work should involve mixed methods and implementation science approaches to explore issues associated with program reach (for example, participant recruitment and formal and informal selection criteria) to further understand the specific mechanisms within self-direction that support recovery. For example, participants’ relationships with their support brokers have been found to be critical for facilitating gains in self-esteem and independence, which were identified as core drivers in recovery (

1). Studies establishing deeper and more nuanced understanding of program effectiveness could inform future research on program- and system-level factors. Future research should also examine cost implications of self-direction across health and social service systems; such information would support mental health leadership in expanding the use of self-direction to enhance self-sufficiency and quality of life.