Communication Strategies to Counter Stigma and Improve Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorder Policy

Abstract

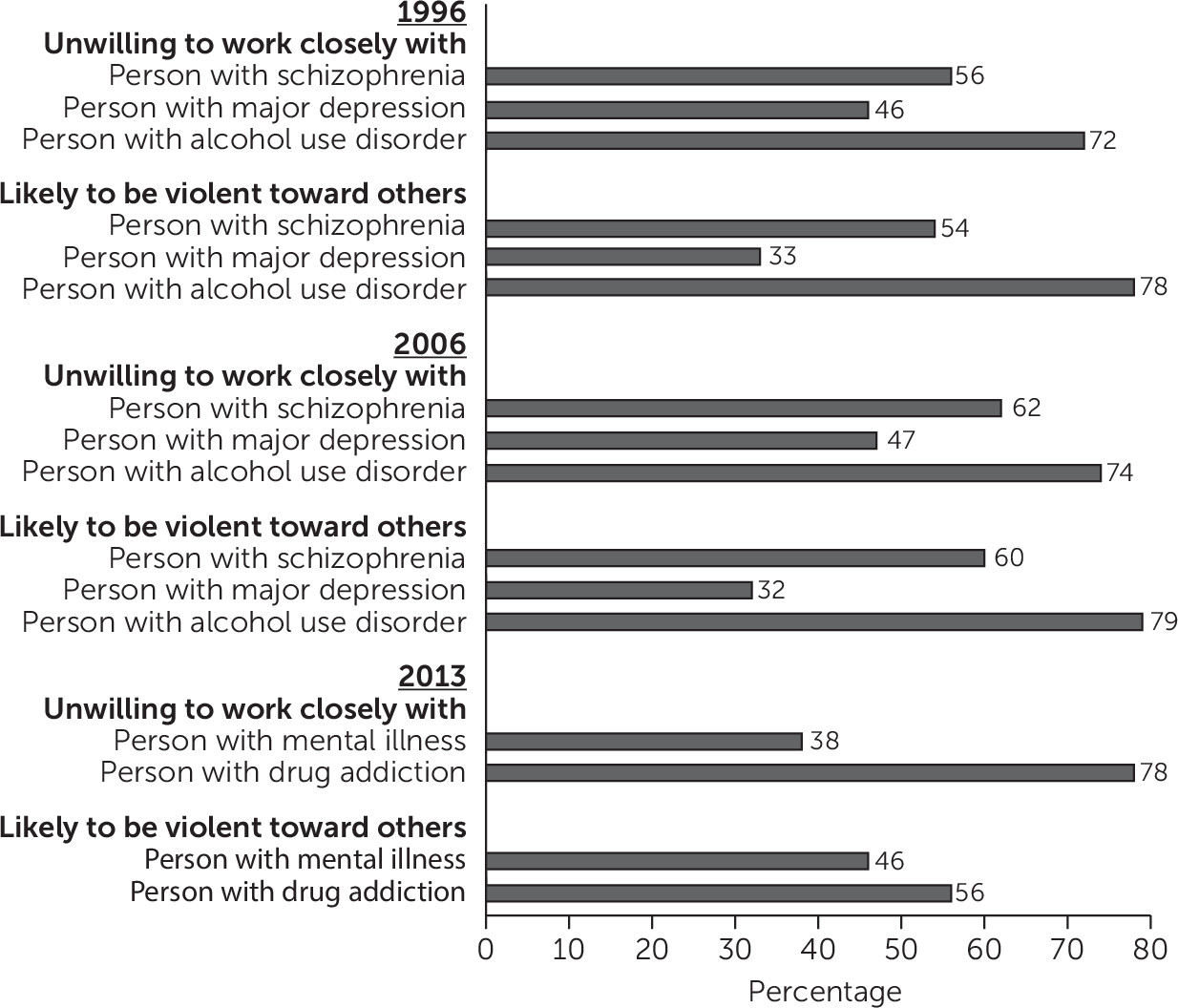

The Role of Stigma in Policy Preferences

Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorder Policy Communication Strategies

| Strategy | Conclusion | Evidence base |

|---|---|---|

| Sympathetic narratives (stories that humanize the experiences and struggles of individuals with mental illness or substance use disorder) | A promising technique for reducing stigma and increasing support for beneficial policies | Narratives can increase audiences’ receptivity to messages by enhancing engagement and eliciting emotional responses. A key strength of narratives is their ability to blend stories about individuals with contextual information about policy issues. By themselves, stories about individuals can prevent audiences from understanding the societal causes of policy problems and decrease support for beneficial public policies. |

| Messages blaming people with mental illness or substance use disorder for their condition | Can decrease the public’s willingness to help these groups and increase support for punitive policy options | Public perception that the affected group is responsible for the problem they face can lead to lower support for policies benefiting and higher support for policies punishing that group. In contrast, when the public views the cause of the problem as outside of individual control, they are more likely to support beneficial policies. Studies show that messages blaming individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders for their conditions are associated with negative emotions, including increased anger and decreased pity; increased desire for social distance and acceptance of discrimination; and increased support for coercive treatment, segregated treatment, and other punitive policies. |

| Messages highlighting structural barriers to mental illness and substance use disorder treatment | Can raise support for beneficial policies without increasing stigma | Messaging strategies highlighting structural barriers to treatment, such as inadequate insurance coverage, provider shortages, and lack of availability of evidence-based services, can increase the public’s willingness to allocate additional resources to mental illness and substance use disorder treatment and do not elevate stigma. |

| Messages emphasizing violence by people with mental illness | May increase public support for expanding mental health services but are stigmatizing; equally effective alternative strategies exist | Messages linking mental illness with interpersonal violence increase public stigma toward this group. Although such messages may increase public support for expanding mental health services, nonstigmatizing messages emphasizing structural barriers to mental illness treatment are equally effective. To date, no experimental studies have examined how depictions of violence by people with substance use disorders influence public stigma and policy attitudes. |

| Messages focused on treatment effectiveness | May reduce stigma associated with mental illness and substance use disorders, but effects on policy preferences are uncertain | Narratives portraying individuals with untreated and symptomatic mental illness and substance use disorders increase public stigma; compared with these depictions, portrayals of people experiencing successful treatment recovery decrease stigma. Studies suggest that on their own, messages about treatment effectiveness may not increase support for expanding mental illness and substance use disorder treatment, potentially because depictions of individuals successfully accessing services fail to convince the public of the need for treatment expansions. Future studies should test narratives combining messages highlighting treatment effectiveness, which may reduce stigma, with messages about structural barriers to treatment, which appear to increase support for expanded services. |

Sympathetic Narratives

Messages Blaming People for Their Condition

Messages Highlighting Structural Barriers to Treatment

Messages Emphasizing Violence by People With Mental Illness

Messages Focused on Treatment Effectiveness

Future Research

| Priority | Evidence base |

|---|---|

| Increase public support for expanding evidence-based substance use disorder treatment | Given the high prevalence and low treatment rates of substance use disorders in the United States, development of communication strategies to increase support for evidence-based policies to prevent and treat substance use disorders is a priority. To succeed, such strategies need to overcome the dominant public perception that people with substance use disorders are to blame for and are in control of their condition. |

| Assess communication strategies to increase public support for harm reduction approaches | Harm reduction strategies aim to reduce negative consequences associated with drug use. Evidence-based harm reduction strategies such as needle exchanges, safe injection facilities, and naloxone administration have been shown to decrease overdose, decrease transmission of HIV and other diseases, and increase rates of treatment. With the exception of naloxone, however, these strategies have not been widely implemented in the United States, in part because of low public support for policies designed to reduce the negative consequences of drug use without eliminating drug use itself. |

| Disentangle the role of race and socioeconomic status in public stigma and support for policies involving mental illness and substance use disorders | Mental illness and substance use disorders are linked in the public’s mind with racial, ethnic, and class characteristics that independently engender stigmatizing attitudes. One of the challenges of overcoming public stigma toward people with mental illness and substance use disorders and garnering public support for policies benefiting these groups is our lack of understanding regarding how much stigma and support for beneficial policies is related to mental illness and substance use disorders themselves versus race, class, or other stigmatizing characteristics. |

| Understand policy feedback—how do perceptions of existing mental illness and substance use disorder policies influence public stigma and support for further policy enactment? | The policy feedback literature shows that enactment of public policies can lead to shifts in public perceptions of the worthiness of the population targeted by the policy and shift political power by creating new constituencies. For example, Medicare is widely credited with increasing public perceptions of older adults as deserving of significant public investment and creating a powerful interest group of beneficiaries. In the mental illness and substance use disorder context, it is particularly important to understand how the growing number of policies designed to ensure equity in how the medical and insurance sectors approach mental illness and substance use disorders relative to other medical conditions, like insurance parity, and how shifts away from punitive drug control policy and toward increased emphasis on prevention and treatment influence public attitudes. |

| Test the effects of rights-oriented messages on public stigma and mental illness and substance use disorder policy preferences | The major mental illness and substance use disorder policy initiatives of the past century, including deinstitutionalization, passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the federal insurance parity law have shared a civil rights orientation, seeking to prohibit discrimination on the basis of mental illness or substance use. To date, however, little is known about how rights-oriented messages influence public stigma and support for mental and substance use disorder policies. Rights-oriented messages have most commonly been applied to mental illness, but the potential for such messages to shift public attitudes about substance use disorder policy issues should also be considered. |

Increasing Public Support for Expanding Treatment

Increasing Public Support for Harm Reduction Approaches

Disentangling the Role of Race and Socioeconomic Status

Understanding Policy Feedback

Testing the Effects of Rights-Oriented Messages

Other Topics for Future Research

Conclusions

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Cover: Frosty Day, by Alexej von Jawlensky, 1915. Oil on paper on cardboard; 10½ by 14 inches. Gift of Benjamin and Lillian Hertzberg, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

History

Keywords

Authors

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).