The need to bring into primary care high-quality treatment and management of depression, anxiety, and other common behavioral health conditions has been well documented (

1,

2). Health care reform efforts are focusing on achieving the “triple aim”: improving population health, improving patient experience of care, and reducing per-capita costs. Health care systems and communities increasingly realize that an integrated behavioral health strategy is essential to achieve the triple aim (

3). The Affordable Care Act has been encouraging health care reform through Medicaid and Medicare, and commercial insurance plans appear to be following suit, thus providing an opportunity for behavioral health integration models to be implemented, disseminated, and sustained. While it remains unclear whether the current movement to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act will affect these efforts, there has been encouraging bipartisan support for legislation in the 21st Century Cures Act, which passed in December 2016. This act supports the prioritization of integration activities that would be likely to encourage innovation at the state level by reauthorizing grants for integration, as well as enforcing existing parity laws (

4).

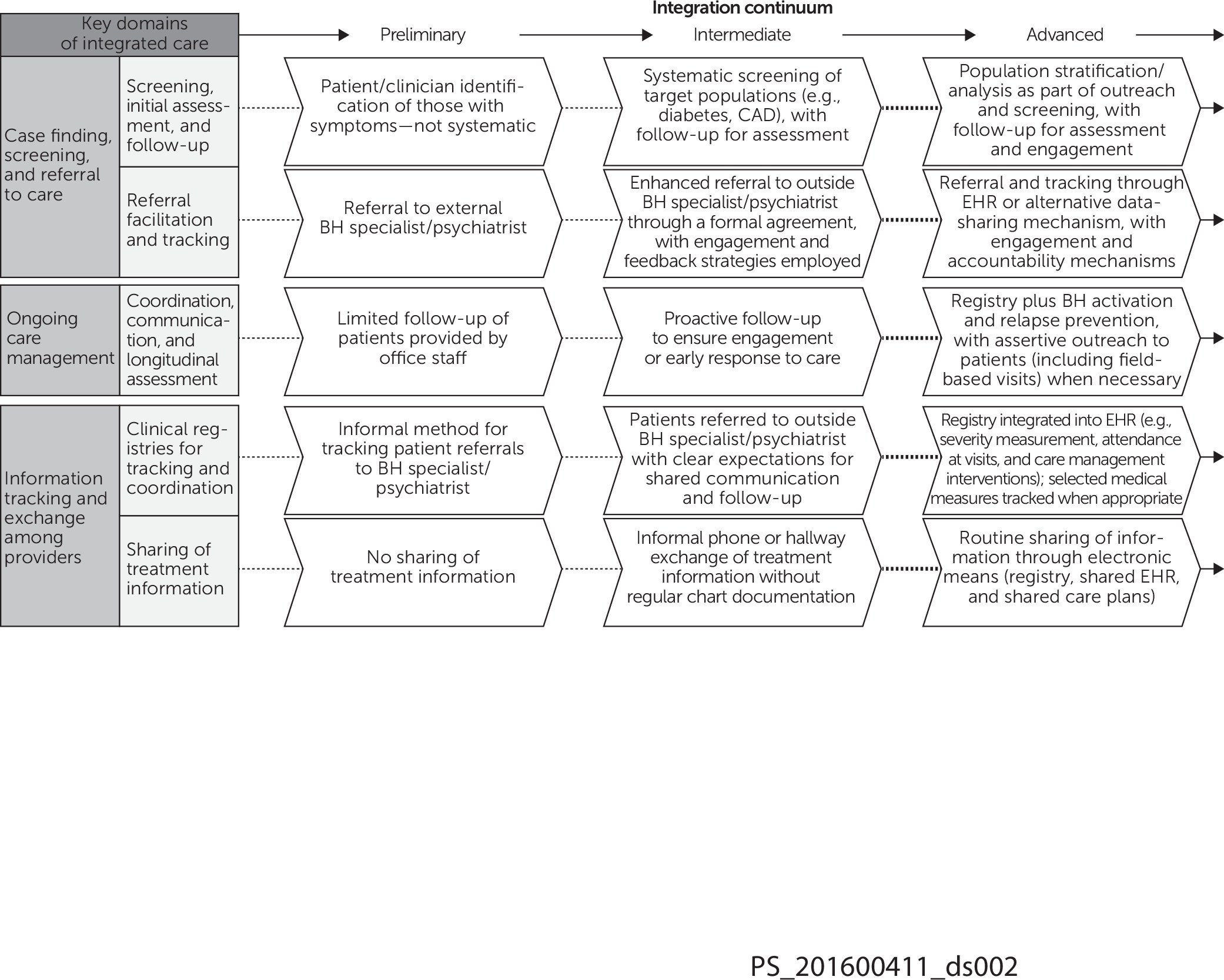

Addressing behavioral health issues in primary care requires significant system changes to bring about meaningful improvement. Adaptations of integrated care models will often vary according to the size, location, and resources of a primary care practice. With these realities in mind, a framework for integrated care was recently created in New York State (NYS) with input from multiple stakeholders in order to support key statewide policy initiatives promoting integration (

5). The framework is based on evidence and is structured on a continuum that can be used as a roadmap while allowing flexibility for implementation and advancement of integration (

Figure 1). This is a departure from previous frameworks, which tend to be more categorical (

6). The framework is intended to aid in the assessment of the current state of practice integration across a range of integration domains (including case finding, screening and referral to care, ongoing care management, and culturally adapted self-management support) and to provide specific guidance for moving forward along the integration continuum, with achievable goals at each step along a domain. The continuum structure recognizes that achieving the most advanced state of each domain and its components will not necessarily be the ultimate target for every primary care practice.

Use of the Framework in NYS

Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment.

The Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) is a transformational model funded via a Medicaid 1115 waiver that rewards providers for performance on delivery system transformation projects that improve care for Medicaid patients. In NYS, the DSRIP has the explicit statewide goal to reduce avoidable hospital use by 25% over five years (

7). Of note, integrated behavioral health is the only transformation project (among a menu of more than 20 possible projects) unanimously chosen as a focus by all funded regional collaborations, dubbed Performing Provider Systems (PPS), participating in New York’s DSRIP (

8). NYS DSRIP offers two integration models in primary care that can be chosen: an enhanced colocation model or a collaborative care/IMPACT model (

9). Each model has significant regulatory, staffing, and workflow requirements, and participating practices and systems tend to be larger and better resourced than nonparticipants. The NYS framework can be used by PPSs participating in DSRIP for assessment of the baseline state, as a roadmap for practice integration for the two models, and for assessment of progress over time.

Advanced Primary Care.

NYS received a state innovation model grant in 2014 supporting its use of the advanced primary care (APC) model to achieve the triple aim. APC is an augmented patient-centered medical home model that will be supported by Medicare, commercial, and Medicaid payers. APC complements DSRIP by allowing practices with majority Medicare and commercially insured patients to participate in primary care transformation projects. APC prioritizes processes and outcomes related to integration, with the overall aim of ensuring that 80% of New Yorkers are receiving value-based care by 2020. Indeed, one of the five “strategic pillars” for transformational change, as outlined by the state, is that patients receive health care services through an integrated care delivery model, with a systematic focus on prevention and coordinated behavioral health care (

10).

The APC model has less onerous resource and workflow documentation requirements than DSRIP, making it more feasible for smaller, independent practices to implement integration, but nonetheless has significant requirements for achieving quality measures (

11).

Practices joining APC will be required to demonstrate the achievement of milestones along with acceptable performance on a robust set of quality measures. The NYS behavioral health integration framework can be used to help practices develop a plan to progress through the “gates” or core practice competencies, in behavioral health integration. For example, at gate 1, it is expected that primary care practices perform a practice self-assessment as well as set concrete goals to achieve the gate 2 milestones of screening, evidence-based treatment, and referral. The framework is uniquely positioned to help practices achieve these initial gates. At gate 3, there is an expectation that sites will be using either the collaborative care model or some form of colocation model. In order to support value-based payment at these gates, practices will need to attest to completion of these goals (subject to audit) as well as be measured on several key behavioral health plan measures developed for APC, such as clinical depression screening and follow-up, antidepressant management, and initiation and engagement of treatment for alcohol and drug dependence. [The APC framework is illustrated in the online supplement to this column.]

Thrive NYC.

Thrive NYC (

https://thrivenyc.cityofnewyork.us) is an initiative to transform the public mental health system of New York City (NYC) (

12). Launched in 2015, it involves many city agencies, including NYC Health and Hospitals, the New York Police Department, the Department of Education, and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and is funded by the City of New York, which invested $850 million over four years, with 54 initiatives. Thrive NYC is founded on six guiding principles: change the culture, act early, close treatment gaps, partner with communities, use data better, and position government to lead. Improving access to mental health treatment is a priority, and Thrive NYC has created the Mental Health Service Corps (MHSC) to promote integration of behavioral health into primary care using an enhanced colocation model similar to NYS DSRIP. It does so by recruiting early-career mental health clinicians for placement in primary care, substance use treatment, and mental health settings citywide with supervision by a psychiatrist. MHSC is using the behavioral health framework to assess the state of integration from selected primary care practices in order to develop a strategic plan to implement elements of its integrated care model, such as an electronic registry, case consultations, and stepped-care referrals, and to measure progress toward performance targets. Finally, the framework will be used to measure the progress of advancing the integration level for MHSC sites (G. Belkin, personal communication, 2016).

Conclusions

In a time of tremendous change in health care, it is reassuring and important that NYS and other U.S. locales have moved behavioral health integration into the forefront of health care reform, especially in the primary care sector. However, given the diversity of primary care practices around NYS, and indeed the country, a common organizing integration framework is needed along with guidance for practices based on geography (urban, suburban, and rural), workforce capacity, training, reimbursement, and culture change. NYS is providing substantial funds and technical assistance to achieve sustainable behavioral health integration in primary care practices, and documenting the progress both at the practice level and aggregate level will be key. The NYS framework builds on the SAMHSA framework by providing a high level of detail for taking concrete steps toward integration while assisting with concrete goal planning across multiple domains. Its flexible, continuum-based approach allows practices at any stage of integration to assess and advance their integration efforts. Looking forward, additional efforts to evaluate the framework for its overall utility as well as for accumulating aggregate data on progress toward advancing integration in multiple primary care practices will be welcome to assess its generalizability for other efforts in the United States.