The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for protecting public health interests by assuring the safety and security of medications (

1). To achieve that goal, the FDA undertakes comparative effectiveness research to determine risks and issue risk warnings when necessary. In October 2004, after conducting a series of meta-analyses and finding an increased risk of suicidality events among paroxetine-treated children, the FDA directed pharmaceutical companies to issue a black box warning on antidepressants about the potential link between the use of antidepressants and suicidal ideation among children (

2–

4). The goal of this study was to analyze the long-run trends in antidepressant use among children before and after the black box warning and to see whether an initial decline in use was followed by a return to rates of use before the warning.

The prescription of antidepressants for children was on the rise along with the diagnoses of depression until 2005, when rates of both prescriptions and diagnoses dropped sharply due to the implementation of the black box warning (

3,

5). Initially, the black box warning resulted in an overall decrease of antidepressant use among both adults and children (

6,

7). The trends in antidepressant use in the years immediately after the warning have been studied extensively; however, most studies since then have focused on retesting the effectiveness and risks of antidepressants for pediatric patients rather than analyzing the long-term effects of the black box warning on antidepressant use (

8–

12).

One such study suggested that “meta-analyses fail to undermine evidence that antidepressants are associated with increased risk of suicidality in children” and that the black box warning on pediatric use of antidepressants are warranted (

10). On the other hand, Lu and colleagues (

12) found that although antidepressant use among youths declined after the black box warning, suicide attempts may have actually increased. This suggests that there may have been unintended negative consequences attributable to the overall decline in treatment for depression (

3,

5) and to the decline in the prescription of antidepressants without the FDA-recommended close monitoring of patients (

13). Understanding national, long-run trends in antidepressant use acts as an indicator of the strength of the black box warning in the midst of conflicting evidence, as well as how providers have reacted to the evolving uncertainty and complexity of youth depression treatment.

Other medication and product warnings have had varied impact on patterns of use (

14–

17). For instance, FDA black box warnings regarding antipsychotic use for patients with Parkinson’s disease and medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among pediatric patients did not decrease the use of these medications (

18), possibly because of the lack of a media campaign (

19). Other product warnings (such as warnings about artificial sweeteners and cigarettes), however, have resulted in sharp drops of product use shortly after a warning, only to be later followed by a renewed increase in product use (

20,

21). Consumer studies show that compliance with warnings depends on a variety of consumer factors that are both design and nondesign related (

22), such as the fact that text labels are more difficult to remember than graphic warning labels (

23) and that for certain products, it is more difficult to implement effective advisories (

24).

Individuals adhere to black box warnings depending on the perceived risks and benefits of the product, which is true for both patients receiving mental health care (

25) as well as providers (

26). These perceived risks are unrelated to the actual risk or even to the risk stated in a warning label (

21,

27,

28). The level of perceived risk is associated with factors such as the visual accessibility of information for consumers (

29) and years of experience and gender for providers (

26). Perceived liability (

30) and provider knowledge (

31) may also affect prescription behavior, regardless of the information provided by the black box warning. Among consumers, a black box warning for antidepressants does increase the perceived risk (

32). On the other hand, consumers with prior continuous use of antidepressants might have a reduced perceived risk, because continuous use of antidepressants reduces the risk of relapse and recurrence of depression (

33). In analyzing perceived risks over time, it is also important to consider the role of the pharmaceutical companies. In response to product sales decreases, pharmaceutical companies have been motivated to downplay warnings after their initial implementation (

34).

Possibly because of changes in these perceived risks and behaviors over time, the 2004 black box warning appears to have a differential effect on antidepressant use among children in the short run and the long run. Analyzing the trends of antidepressant use among children is the first step toward understanding the long-run response of consumers, providers, and manufacturers to risk warnings. In this study, we examined the long-run effect of the black box warning on antidepressant use and determined whether the impact differs between the populations with severe and nonsevere psychological impairment. We divided the postwarning years into two time periods—early postwarning (2004–2007) and late postwarning (2008–2011)—to differentiate the short-run and long-run impact of the warning on rates of use. The cutoff year chosen was 2007 because of FDA’s revision to the black box warning that year and to better accommodate the initial uncertainty that may have been associated with the 2004–2007 time period.

Methods

Data

For our analysis, we used data for children ages five to 17 from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) covering years 2000–2011. This age range corresponds to the population targeted by the FDA black box warning. MEPS is a nationally representative survey of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population. Approximately 15,000 individuals are newly surveyed each year about their health care use, demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, and physical and mental health status. Our final sample included 75,819 children ages five to 17.

Psychological impairment in our analysis was defined by using the Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) score, which is reported as part of the MEPS data. CIS is a 13-item global measure of impairment administered to parents by an interviewer. It addresses four areas of functioning (interpersonal relations, broad psychopathological domains, functioning in job or school, and use of leisure time), and it has been used in prior studies of trends among youths (

35). Items are scored on a range of 0 to 4, with total scores ranging from 0 to 52. This is a parent-reported instrument that correlates well with clinicians’ Children’s Global Assessment Scale score (

36). A CIS score of ≥16 was used to indicate severe psychological impairment (

37).

The dependent variable of interest was any antidepressant use at a given year. Using the prescription names listed in the MEPS prescription files, we identified the children with any antidepressant use in a given year. [The list of antidepressant prescription names included in our definition can be found in an online supplement to this article.] We included a broad list of antidepressants that might be used among children and adolescents for purposes other than depression. Removing these medications from our list (such as amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine, and trazodone) did not make a difference in terms of the direction or magnitude of our findings.

The additional covariates used in our models were age, race, gender, income level, insurance status, health status, and metropolitan statistical area (MSA). Age was calculated from date of birth and indicates age status as of December 31 of each year; it was categorized into three groups (

5–

17). Insurance status indicates the respondents’ insurance coverage by private insurance; Medicaid (including the State Children's Health Insurance Program) or Medicare; other public insurance; or uninsured. Income is denoted as a categorical variable: below poverty (<100% of the federal poverty level [FPL]), near poverty (100%−125% of FPL), low income (125%−200% of FPL), middle income (200%−400% of FPL), and high income (>400% of FPL). The race and ethnicity variable was coded by using three Census-based categories: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic. Other racial and ethnic groups were excluded from the sample because of small samples. Health status measured perceived health status, given that the respondents were asked to rate their health according to the following categories: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor.

Statistical Approach

To estimate how the impact of the black box warning on antidepressant use among children changes over time, we first divided the entire sample period (2000–2011) into four periods: early prewarning (2000–2001), prewarning (2002–2003), early postwarning (2004–2007), and late postwarning (2008–2011). Then, we estimated the short-run and long-run impact of the warning on antidepressant use using a multivariate probit model:

where

y is any antidepressant use at a given year;

X is vector of explanatory variables, including gender, age, race, income, health status, insurance status, and MSA; Time is the categorical variable that denotes the time periods of early prewarning, prewarning, early postwarning, and late postwarning; and G(.) is the cumulative distribution function of standard normal distribution. The main coefficient of interest is β

1, which denotes the short-run (early postwarning) and long-run (late postwarning) impact of the warning compared with the prewarning years.

Sample years before the warning were divided into two categories, early prewarning (2000–2001) and prewarning (2002–2003). The prewarning period (2002–2003) was used as the reference category, mainly because of the noticeable difference in antidepressant use rates between these two periods, with the years 2002–2003 more representative of the antidepressant use trends right before the warning.

We used the coefficient estimates from the model in the equation above to generate recycled predictions, also called the predictive margins method, to estimate the regression-adjusted yearly predicted probability of use (

38). The standard errors of the predicted probabilities were estimated by using bootstrap methods (N=500) (

39). In all of our analyses, we adjusted for the sampling design used in the MEPS, including the estimation weight, sampling strata, and primary sampling unit (

40). We estimated the probit model in the equation above for children with and without severe psychological impairment to explore whether the long-run effects were different between the two populations. Goodness of fit in all models was verified by using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test [see

online supplement] (

41).

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the final sample, which included 75,819 children ages five to 17. Approximately half of the sample was female (48.9%), the predominant race was non-Hispanic white (42.0%), and most of the children were insured (90.4%). Only 27.7% of the children lived in households with incomes below the FPL, and 1.5% reported the use of any antidepressants. In our final sample, 19.2% of the children (N=14,523) were considered to have severe psychological impairment (CIS score ≥16). The prevalence of antidepressant use differed noticeably between those with severe psychiatric impairment and those without (5.0% and .7%, respectively).

The probit regression results are presented in

Table 2, and they include estimates for the total sample in addition to the subsamples of children with or without severe psychiatric impairment. Among all children, after adjustment for all covariates, there was a significant decline of .5% in the probability of using any antidepressants during the early postwarning years (2004–2007) compared with the prewarning years (2002–2003) (coefficient=–.13, p<.01). In the long run, however, there was no statistically significant difference. In the late postwarning years (2008–2011), the probability of use was not significantly different than in the prewarning years (2002–2003) at any conventional level.

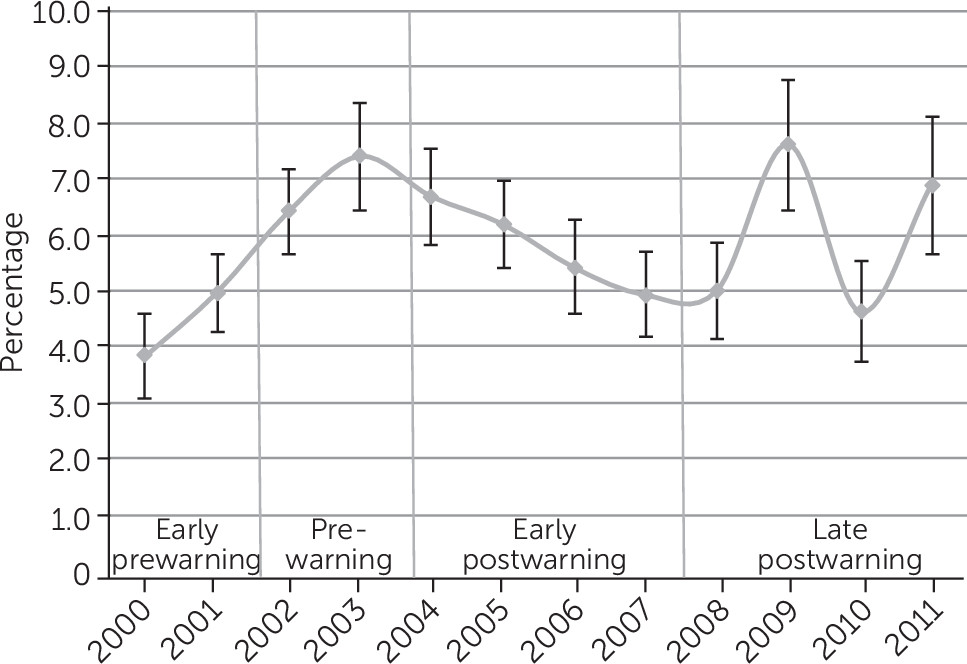

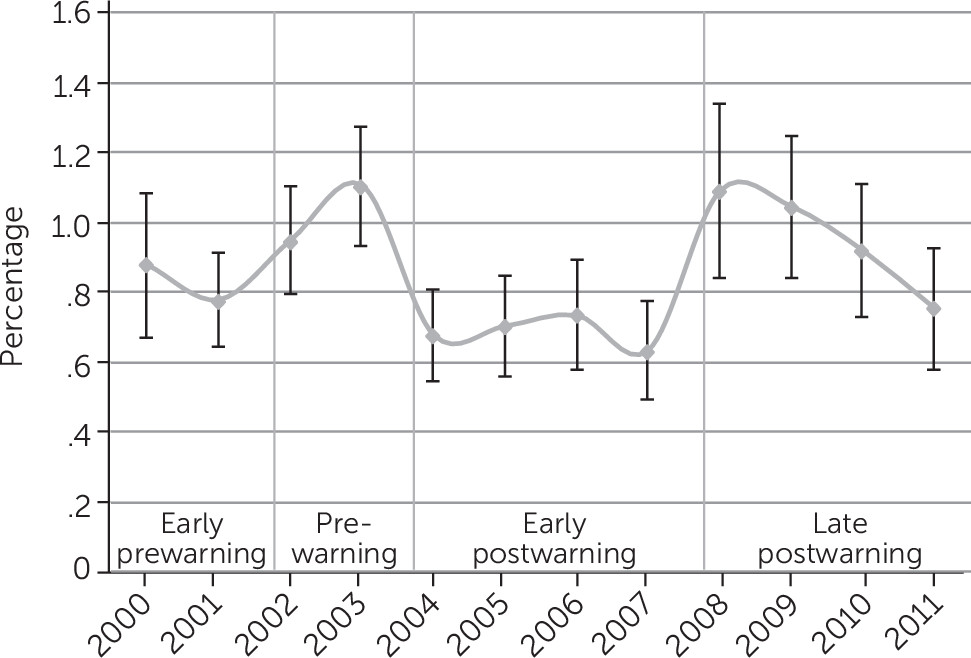

The results also showed that short-term impact of the black box warning differed between the population with severe psychological impairment and the population with nonsevere psychological impairment. Among children with severe psychological impairment, there was no significant decline in the probability of using antidepressants during the early postwarning years (2004–2007), compared with the prewarning years (2002–2003) (p=.17). However, those with nonsevere psychological impairment were .3% less likely to use antidepressants in the early postwarning years compared with the prewarning years (2002–2003), and the effect was significant (coefficient=–.16, p<.01). Neither the severe nor the nonsevere psychological impairment population showed significant decline in antidepressant use in the late postwarning years (2008–2011), compared with the prewarning years (2002–2003). In other words, antidepressant use in the late postwarning years did not significantly differ from the prewarning years in either population.

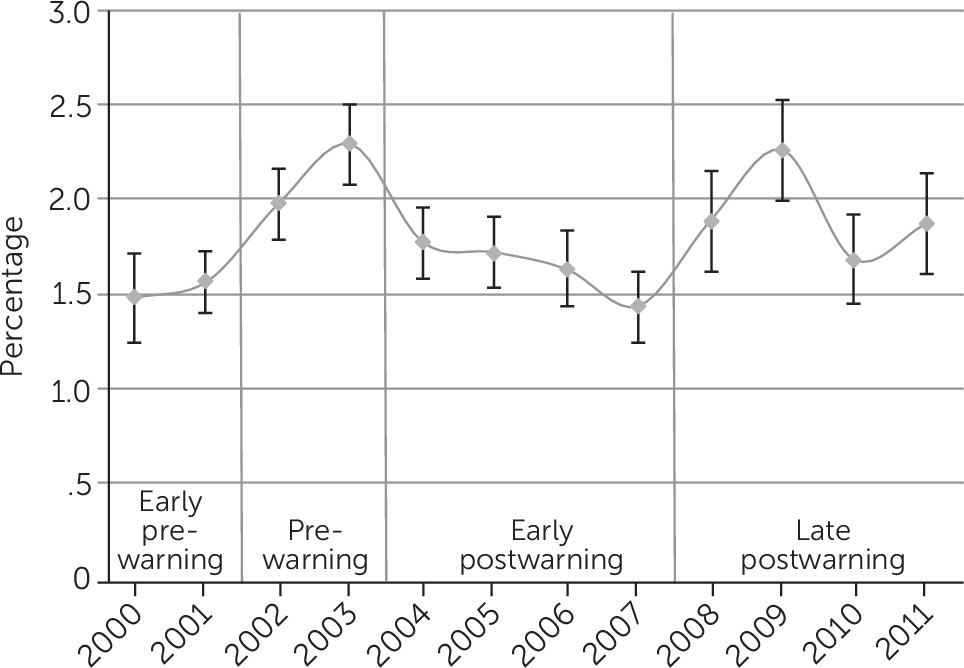

Figures 1–

3 present the regression-adjusted yearly trends in antidepressant use from 2000 to 2011 among the three samples of interest: all children ages five to 17, those with severe psychological impairment, and those with nonsevere psychological impairment. Five years after the warning in 2009, the adjusted rates of use increased to the prewarning level in 2003 (2.29% in 2003 and 2.26% in 2009) (

Figure 1). The initial decrease in antidepressant use after the warning was not prominent among children with severe psychological impairment, as represented by the early postwarning area in

Figure 2. However, we observed an almost perfect U-shaped trend among children with nonsevere psychological impairment in

Figure 3, which shows that the rate of antidepressant use in 2008 (1.09%) was almost identical to the rate in 2003 (prewarning) (1.10%).

As a sensitivity check on our findings, to support the argument that initial decline in use was indeed due to the black box warning and not a trend that is present in all populations, we also examined the same trends among the adult population. We found no spillover effects of the black box warning on the adult population [see online supplement]. There was no decline in antidepressant rates in the early postwarning or late postwarning periods in the adult sample. On the contrary, adults’ rates of any antidepressant use were significantly higher (not lower) than the prewarning period in both the early (2004–2007) and the late postwarning (2008–2011) periods (p<.001).

Discussion and Conclusions

We found a .5% statistically significant decline in antidepressant use in the years immediately following the black box warning, suggesting that the diffusion of risk information was effective at reducing rates of use in the short run. However, the initial impact of the warning seemed to fade away in the long run, as the prevalence of antidepressant use returned to the prewarning year levels by 2009. We also found that the initial impact of the warning differed between the population with severe psychological impairment and the population with nonsevere psychological impairment. The warning appeared to have a stronger effect on children without severe psychological impairment. As shown by the regression-adjusted annual trends, the U-shaped trend of immediate decrease in use, followed by a return to the prewarning levels was most prominent among children with nonsevere psychological impairment. Among those with severe psychological impairment, there was a slight decline in antidepressant use until 2008, but the change in prevalence did not appear as dramatic and was not significant.

These findings suggest that providers and families of youths may have reacted to the black box warning in an appropriate manner, weighing the warning with the risks and benefits of the treatment, deciding not to use the medication when psychological impairment was low, and choosing to use the medication when impairment was high and the benefits outweighed the risks. A return to the rates of antidepressant use before the black box warning raises concern that this thoughtful accounting of the risks and benefits may have dissipated over time. The period of increased caution might have been followed by a return to previous levels after newly available information on the warning was assessed properly.

An important policy implication of our findings could be that more frequent updates of FDA risk warnings might be necessary to prevent patients and the providers from “forgetting” the potential risks outlined in the original warning. Methods have been suggested to increase the long-run effectiveness of warnings for both medical and nonmedical products. For example, a study of the warning labels for cigarettes found that designs should be rotated regularly and that they should be simple text accompanied with images (

42). Complex advisories are likely to be ignored by consumers, and effective advisories should be tailored to specific consumers (

43). Label design has a significant impact on warning label effectiveness (

44). A careful review of the successes and failures of different consumer advisories can show how to best increase the long-run effectiveness of pediatric antidepressant risk warnings.

One limitation of this study is the methodology used to determine the severity of depression. Even though the CIS is commonly used in clinical settings, it is not specific to the assessment of depression severity. The indicator of severe psychological impairment that we used was based on the CIS score and serves as only a proxy to the respondents’ actual level of severity and need for antidepressants.

An interesting future research question that is not within the scope of this article is whether the short-run and long-run trends observed in antidepressant use was driven by provider or patient behavior. Some research has suggested that both patient and provider behaviors have changed because of the warning (

45–

47), but studies have focused mostly on the decreased treatment of depression (

5) or the lapses in heeding the black box warning in ambulatory services (

11). Another related research area is the appropriate clinical reaction to this specific FDA black box warning. Rather than the black box warning resulting simply in fewer prescriptions, some researchers have advised that the warning should also result in increased monitoring of children on antidepressants or an increase in alternative treatment, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal counseling (

48), and psychosocial treatment (

49).