In the United States, more than two million people with serious mental illness are booked into jails each year, and the rate of mental illness in the criminal justice population is three to four times greater than in the general population (

1). Justice-involved people with mental illness embody a high-cost, high-need, and high-risk group. Specifically, this group incurs double the cost in mental health, substance abuse, and justice services compared with people with mental illness who are not involved in the justice system (

2). Similarly, jails spend two to three times more for inmates with mental illness than for inmates without mental illness (

3). In part, these costs accrue because justice-involved people with mental illness often have pronounced needs (for example, homelessness and poor health), multiple risk factors for recidivism (for example, substance abuse, antisocial associates, and procriminal attitudes), and high rates of reincarceration (

4; unpublished report, Skeem and Peterson, 2011 [

http://risk-resilience.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/journal-articles/files/major_risk_factors_for_recidivism_among_offenders_with_mental_illness_2011.pdf]).

There is a well-recognized need to intervene more effectively with justice-involved people with mental illness. In fact, over 375 counties have joined “Step Up,” a national initiative to reduce the number of people with mental illness in jail (

5).

Specialty mental health probation is a promising intervention that policy makers could use as leverage in these efforts (

6,

7). Probation involves supervision in the community as an alternative to incarceration; it is the most common form of sentencing in the United States and has become a cornerstone of policies designed to reduce incarceration—partly because services delivered in the community cost less and reduce recidivism better than services delivered behind bars (

8,

9). Compared with traditional probation, which usually involves heterogeneous caseloads of more than 100 individuals, specialty probation is distinguished by small caseloads (fewer than 50 individuals) comprised solely of people with mental illness, sustained officer training in mental illness, and officer involvement in clients’ treatment (

10). In specialty agencies, officers balance control of the individual’s behavior (surveillance) with participation in the delivery of care (rehabilitation), and they stress linkage with psychiatric services as a key to reduction in recidivism (

11,

12).

The few rigorous studies of the effects of specialty probation provide evidence that it reduces recidivism. Based on the sample in this study, we found that the odds of rearrest two years after probation placement were 2.68 times higher for clients on traditional probation than for clients on specialty probation. Estimated rearrest probabilities for the two groups were 54% and 29%, respectively—and the effects endured for at least five years (

13). These results are consistent with those of a quasi-experiment based on administrative data, which indicated a greater decrease in jail days over six months for clients in specialty probation, compared with clients in traditional probation who received any mental health services (

14).

Specialty mental health probation appears underutilized. A decade ago, about 130 agencies had implemented specialty probation (

14)—whereas implementation of mental health courts (MHCs), a more recent invention, was climbing rapidly to 300 or more (

15). Specialty probation might achieve broader uptake if its value was understood. Policymakers are interested in alternatives to jail that are not only evidence based but also cost

-effective (

5). Although specialty probation has been shown to improve public safety outcomes, whether it merely shifts costs from the criminal justice to the behavioral health care system or results in net cost savings is unknown.

In this article, we describe the results of a longitudinal, multimethod study with two aims. Aim 1 was to compare the costs incurred over a two-year period by people with mental illness who were placed on specialty probation versus traditional probation. We hypothesized that specialty probation would result in net cost savings because, theoretically, it meets the needs of people with mental illness more effectively and efficiently than traditional probation. Aim 2 was to describe the extent to which savings achieved through use of specialty probation were attributable to savings in the criminal justice system, the behavioral health care system, or both. We hypothesized that greater expenditures on probation supervision and outpatient treatment in specialty probation would be offset by recidivism-related savings.

Our analysis was conducted from a taxpayer’s perspective, with a focus on the costs of providing criminal justice services and behavioral health care across public sources, from the municipal to the federal level. The goal was to inform policy makers about specialty probation’s return on investment to help drive public dollars into programs that deliver strong outcomes at low cost.

This study appears to be the first examination of the costs of specialty probation. In a sister study of MHCs that used a similar approach, Steadman and colleagues (

16) found that three years after enrollment, MHC participants incurred greater net costs compared with participants in a matched control group. Although the criminal justice costs of the two groups were comparable, behavioral health care costs for the MHC participants were about $4,000 more per year than for the control group. Because specialty probation had a stronger effect on arrests in this study (

13) compared with the MHC study (

16), we expected specialty probation to yield net cost savings.

Methods

Procedures

This cost analysis was part of a larger quasi-experiment that compared public safety outcomes of matched groups of clients placed in specialty versus traditional supervision. Based on a national survey (

10), two probation agencies were selected that exemplified specialty and traditional probation (located in Texas and California, respectively). Agencies were chosen based on similarities in jurisdiction size, client characteristics, and county mental health expenditures.

Clients and officers were assessed three times in the year after placement; probation records were reviewed on the same schedule. Administrative databases were integrated to capture clients’ behavioral health care services and criminal justice contacts for at least two years postplacement. As explained later, unit costs were attached to these data to estimate the cost incurred by each client, for example, by multiplying the number of arrests by the cost per arrest. The protocol was approved by several institutional review boards.

Participants

Eligibility criteria for the study included age between 18 and 65, English speaker, active probation with at least one year remaining on probation term, capability of providing informed consent, and having been identified as having mental health problems (without an intellectual disability). At the specialty probation site, clients were referred to the program by traditional officers, psychologically evaluated, and diagnosed as having a mental illness. Of 248 eligible clients assigned to specialty caseloads, 183 (74%) enrolled.

At the traditional probation site, officers referred clients with documented psychiatric problems, prescriptions for psychotropic medication, or a history of psychiatric hospitalization to the study, and researchers verified mental health problems by administering validated screening tools (

12). Attempts were made to enroll clients from the traditional program who matched clients in the specialty program by gender, age, race, length of probation, and offense type. Of 311 eligible and matched clients, 176 (57%) enrolled.

There were no significant demographic differences between clients who did—and did not—enroll. Clients in both the specialty and traditional programs were ethnically diverse men and women with similar characteristics across the matching variables. Their average Colorado Symptom Inventory (

17) scores fell near the cut score of 30 for psychiatric disability (

18), indicating serious mental illness.

Covariates

In estimating the difference in cost between probation conditions, we addressed potential confounding introduced by nonrandom assignment by controlling for covariates that theoretically predicted both treatment assignment (specialty versus traditional) and outcomes (costs). As detailed in our earlier study (

13), the covariate set consisted of 21 variables that included participants’ demographic characteristics and socioeconomic status; history of criminal behavior and childhood abuse (

19); and substance abuse, externalizing. and other psychiatric symptoms, based on results of the Personality Assessment Inventory (

20), the Colorado Symptom Index (

17), and the Global Assessment of Functioning (

21). Together, these covariates accounted for baseline differences between the groups on a range of demographic, clinical, and criminal characteristics.

Intervention

We directly measured the implementation of specialty and traditional probation—as detailed previously (

12). Briefly, specialty clients were assigned to small caseloads that consisted exclusively of people with mental illness and that were supervised by officers with relevant expertise. Average caseload sizes for specialty probation officers (N=15) and traditional probation officers (N=87) were approximately 50 and 100 clients, respectively. Compared with traditional probation officers, specialty probation officers established higher-quality relationships with clients, participated more directly in treatment, and relied more on positive compliance strategies than on sanction threats. Participants in specialty probation were more likely than participants in traditional probation to receive mental health treatment (91% and 60%, respectively) and treatment for co-occurring mental and substance use disorders (34% and 15%, respectively) within one year of placement, but they were no more likely to receive substance use disorder treatment (28% and 31%, respectively (

13).

Cost Estimates

We used Steadman et al.’s (

16) two-step approach to calculate the costs incurred by each client during a two-year period after placement. First, we obtained administrative data to characterize each client’s service use and criminal justice contacts. Service use was operationalized as Medicaid-reimbursable behavioral health care service events, obtained from county-level administrative databases. Criminal justice contacts were operationalized as probation supervision days (from county databases), arrests (from Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI] rap sheets), and jail and prison nights (from county and state databases). Second, for each service event and criminal justice contact, we attached a unit cost (for example, $1,523 per inpatient night)—which permitted total costs in each category to be calculated. Beyond macro-level categories (behavioral health, criminal justice, and total), we examined subcategories for behavioral health (outpatient care versus emergency room care, hospitalization, or residential treatment) and criminal justice (supervision versus arrests and days incarcerated).

We applied the same estimated unit cost to data from both sites, given our focus on the relative cost of specialty and traditional probation. Unit costs were based on published, multisite estimates, when available. All unit costs were adjusted to the 2008 Consumer Price Index by using urban consumer yearly averages from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Although we strove to derive methodologically comparable unit costs, it was necessary to rely upon multiple sources, which is a common study limitation (

22). Following Steadman et al. (

16), estimated costs per unit for behavioral health services were chiefly based on the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey event files (

MEPS.ahrq.gov), supplemented by cost estimates for nonmedical support services from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (

23). Estimated unit costs for criminal justice contacts were based on three sources. The estimated cost of an arrest was based on Clark et al.’s (

24) study of people with co-occurring mental and substance abuse disorders. The estimated cost of a day in jail and a day in prison were based on McCollister et al.’s (

25) study of people with substance abuse disorders, supplemented by national estimates by Perkins et al. (

26) and the Pew Center (

27). The estimated cost per day of traditional probation supervision was based on the national estimate by the Pew Center (

27); specialty mental health supervision was estimated to cost 1.97 times more, given Texas legislative data (

28) and Pew’s (

27) relative estimates for regular versus intensive supervision.

Analyses

Because participants were not randomly assigned to probation type, it would be misleading to statistically compare raw, average cost estimates for traditional and specialty groups. To rigorously control for potential confounders, we used targeted maximum-likelihood estimation (TMLE), in tandem with a data-adaptive algorithm called SuperLearner, to estimate the average difference in cost between groups.

TMLE is a double-robust, semiparametric estimator that uses estimates of both the treatment mechanism (that is, the propensity score [the probability of specialty probation assignment, given covariates]) and the outcome regression (that is, the expected cost, given probation type and covariates). This estimation technique is especially suitable for the current study because the estimator does not solely rely on a correctly specified model of the outcome regression or treatment assignment process, which we did not know because the study was observational (

29).

Within TMLE, we used the SuperLearner algorithm to estimate the treatment mechanism and outcome regression. SuperLearner combines a library of machine-learning algorithms and parametric models to build an estimator that performs as well as—or better than—any candidate algorithm in the library, if the library does not contain a correctly specified parametric model (

30). SuperLearner was useful for addressing our study aims because the outcome variable—cost—is characterized by outliers (a few participants with extremely high costs), zero inflation (many participants with no cost), and high variability (costs from $0 to $100,000). SuperLearner includes algorithms that are robust to outliers and does not depend on the variable’s distribution having a certain shape (for example, nonparametric algorithms including classification and regression trees). [More information about the algorithms is available online in a

data supplement to this article.] Moreover, SuperLearner includes a cross-validation step that assigns greater weight to the algorithms in which predictions deviate the least from the observed values (decreasing sensitivity to outliers) and assesses the performance of candidate algorithms to avoid overfitting.

Analyses were performed by using R, version 3.3.3—using the “tmle” package for TMLE analyses (

31) and the “SuperLearner” package to estimate the treatment mechanism and outcome regression (

32).

Results

Aim 1: Comparing Two-Year Costs

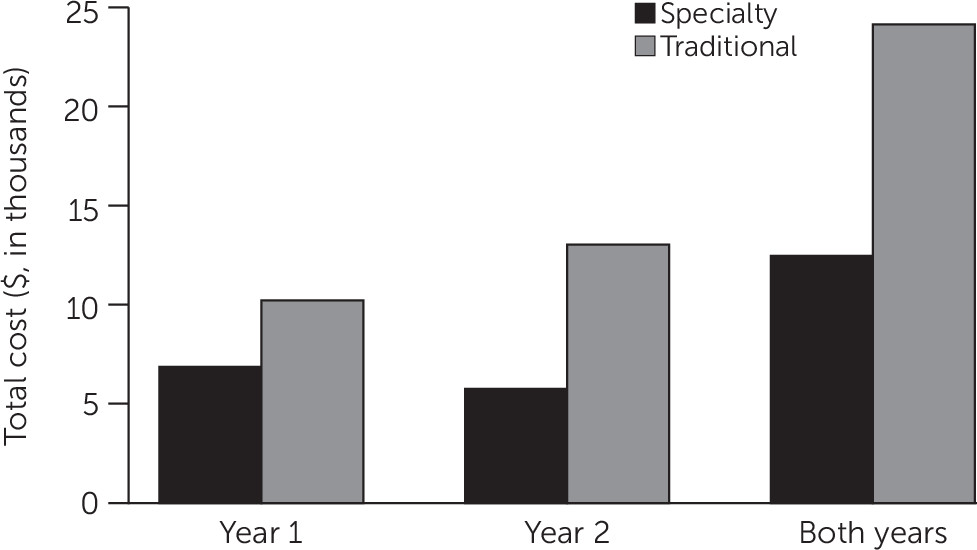

Table 1 shows a comparison of participants’ baseline characteristics before adjustment by TMLE for potential confounders. To compare the costs incurred over a two-year period by people with mental illness placed in specialty versus traditional probation, we collapsed costs across criminal justice and behavioral health care domains (

Figure 1). As hypothesized, specialty probation resulted in net cost savings. As shown in

Table 2, adjusted estimates showed that specialty probation cost $11,826 less per client over two years than traditional probation (p<.001). Specialty and traditional probation cost an average of about $12,349 and $24,174, respectively, per client, a cost savings of 51% for specialty probation. A large proportion of the savings appeared in the second year.

Aim 2: Chief Components of Cost-Effectiveness

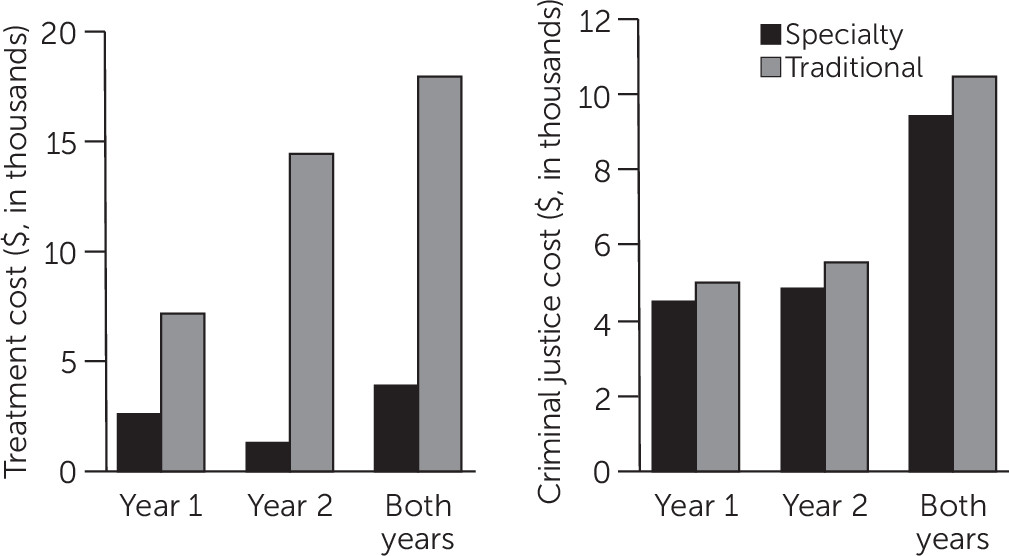

To describe the extent to which specialty probation reflected savings in criminal justice, behavioral health, or both systems, we examined each system’s costs separately. As shown in

Figure 2, contrary to our hypothesis, most cost savings for specialty probation came from the behavioral health care domain rather than from the criminal justice domain. Over two years, average estimated behavioral health care costs for a client in traditional probation exceeded those for a client in specialty probation by $14,049 (p<.001)—again with much of the difference occurring in the second year (

Table 2). In contrast, there were no significant group differences in criminal justice costs.

To identify the source of the significantly greater costs in service use for traditional rather than specialty supervision, we disaggregated costs in this domain. As shown in

Table 2, the behavioral health care savings associated with specialty probation were driven by reduced reliance on emergency, inpatient, and residential services—the average two-year costs per client for these services were $30,694 less in the specialty program than in traditional supervision (p

<.001). At the same time, outpatient services cost an estimated $1,141 more per client in specialty probation compared with traditional supervision, with much of the difference occurring in the first year (p=.008) (

Table 2).

Finally, we disaggregated criminal justice costs to determine whether the greater cost of small specialty caseloads was offset by reduced recidivism and other justice costs. As shown in

Table 2, supervision costs were significantly higher for clients in specialty probation than for clients in traditional probation—despite no significant group differences in total criminal justice costs. Thus the higher cost of reduced caseloads in specialty probation was offset by other justice savings.

Discussion

Today’s policy makers are interested in evidence-based, cost

-effective alternatives to incarceration for people with mental illness (

5). Specialty mental health probation has been shown to reduce recidivism (

13,

14). To test the value of specialty probation, we conducted a multimethod quasi-experiment and applied TMLE, a doubly robust approach, to statistically “break” associations between any confounding variables and both treatment assignment and cost outcomes. We found that overall, specialty probation cost nearly $12,000 less per client over a two-year period than traditional probation—a net savings to taxpayers of 51%.

These cost savings were not simply attributable to reduced recidivism. Specialty and traditional probation were similar in criminal justice costs, despite greater costs for supervision of specialty caseloads. That is because these costs were completely offset by savings in reduced recidivism. But specialty probation cost less than traditional probation in behavioral health care. Specifically, the cost of outpatient services was marginally greater in specialty probation than in traditional probation. However, these costs were more than offset by lower costs for emergency, inpatient, and residential services. This finding is consistent with the results of an experiment that evaluated forensic assertive community treatment (FACT) (

33)—although outpatient costs for FACT are unusually high and were not completely offset by inpatient savings. We hope that a future experiment will test our hypothesis that specialty probation reduces behavioral health care costs by providing well-coordinated outpatient services that prevent psychiatric crises (

34).

Although the behavioral health care system may accrue greater cost savings than the criminal justice system from specialty probation, the use of specialty probation offers a range of incentives to criminal justice stakeholders. Specifically, specialty probation costs the justice system no more than traditional probation, is valued by probation personnel as an efficient means of supervising clients often perceived as dangerous and difficult to supervise (

12), and reduces recidivism (

13,

14)—which is central to the justice system’s public safety mission. Overall, specialty probation seems to be an efficient intervention for justice-involved people with mental illness, particularly compared with mental health courts, which inadvertently involve lengthy jail stays (

16,

35), and FACT teams that provide intensive outpatient treatment (

36).

Importantly, the positive effects observed here are unlikely to generalize to nonprototypic agencies; results of a national survey suggest that as “specialty” agencies increase caseload sizes above 45, they function more like traditional agencies (

10). Agencies must allocate resources to permit high-fidelity implementation of specialty caseloads. Some hallmarks of specialty probation—such as establishing firm, fair, and caring relationships with clients—are also staples of evidence-based practice in community corrections (

37,

38) and are well worth the investment.

This study’s chief limitation was that participants were not randomly assigned to probation types; instead, specialty probation clients and traditional probation clients were drawn from different jurisdictions, introducing potential confounds. We address this limitation in three ways. First, we used TMLE and included a rich set of 21 covariates to adjust for as many possible confounders as possible. Second, we consulted FBI comparison data (retrieved on January 16, 2017, at

www.ucrdatatool.gov), which suggest that the effects of specialty probation were not an artifact of local practices. In fact, arrest rates were slightly higher in the jurisdiction of the specialty probation clients. Third, to enable direct cost comparisons, we applied the same unit costs across sites for service use and criminal justice contacts. Together, these points—along with sample matching, precise measurement, and strong implementation—lent substantial confidence to our results. Nevertheless, it is essential that the findings be replicated in a randomized controlled trial.

Conclusions

Well-implemented specialty mental health probation yielded substantial cost savings compared with traditional probation—and should be considered in current justice reform efforts for people with mental illness.

Acknowledgments

Data for this study were collected, entered, and cleaned by staff and volunteers in California and Texas who are affiliates of the Risk Resilience Lab (originally based at the University of California, Irvine, and now based at the University of California, Berkeley). The authors thank Jennifer Eno Louden and Patrick Kennealy for their comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.