Opioid misuse is a major public health crisis in the United States. Among adolescents, the rate of drug overdose deaths involving opioids increased from 1.6 per 100,000 in 1999 to 3.7 per 100,000 in 2015 (

1). Between 2008 and 2014, opioid-related emergency department visits doubled for individuals ages 1–24 (

2). Use of prescribed opioid analgesics before high school graduation is associated with a 33% increase in the risk of later opioid misuse (

3). By the end of high school, approximately 13% of adolescents have used prescription opioids nonmedically (

4), and misuse of opioid pain medications in adolescence strongly predicts later onset of heroin use (

5).

Opioid misuse often begins with a medical prescription for pain relief (

4,

6). For adolescents, opioids can be prescribed for short-duration pain related to a procedure or an acute injury (

7). Rarely, some adolescents may have chronic conditions, including cancer, for which opioids are prescribed for longer-term use. Adolescents may be more susceptible than adults to misuse of prescribed opioid medications (

8).

Because of the potential harms of overprescribing opioids, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued opioid-prescribing guidelines in 2016 that recommend limiting opioid use as a first-line therapy for chronic pain and not prescribing extra pills “just in case” for acute pain (

9). The CDC guidelines further recommend that adult prescriptions for acute pain should be limited to the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids (typically no more than three days) to minimize abuse and diversion (

9). Both the CDC guidelines and other literature indicate that opioids should be prescribed to adolescents more cautiously than to older age groups because of a lack of studies testing efficacy in this population and because teens are at a critical window of vulnerability for substance use disorders (

8,

9).

In addition to the CDC guidelines, states increasingly are enacting laws or promulgating regulations to reduce the days’ supply of opioid medications prescribed. For example, Massachusetts imposes a seven-day supply limitation for initial prescriptions to adults and for any prescription to minors, with additional requirements for prescribing to minors, such as consultation with the legal custodian (

10). Other states—for example, Connecticut (

11)— have amended those restrictions to further limit prescriptions for minors to five days. Some states, however, are even more restrictive, such as Ohio, which limits a prescription to 72 hours if the party authorizing treatment for the minor is not the parent or guardian (

12). Vermont limits prescriptions for minors for moderate to severe acute pain to three days (

13), and Minnesota limits prescriptions for everyone to four days for any acute dental pain (

14). The latter would include opioid prescriptions following wisdom tooth extraction, a common source of misused opioids among minors and young adults (

15). It is anticipated that laws such as these will become increasingly common and possibly more restrictive. With that in mind, we sought to understand trends in days’ supply for adolescents over a 12-year period during the development of the opioid crisis. The CDC recommendations were issued in 2016, the last year of the study time frame.

Methods

In this study, we conducted a descriptive analysis of opioid pharmacy claims to understand levels and change in opioid prescribing to adolescents starting in 2005. We measured opioid days’ supply for both Medicaid and commercial insurance by using the 2005–2016 IBM MarketScan commercial and Medicaid databases. The MarketScan commercial database includes insurance claims from over 200 million employees and dependents covered by large, self-insured employers and by regional health plans. The MarketScan Medicaid database contains claims of approximately 30 million enrollees with public insurance (Medicaid) from multiple states. The MarketScan databases are consistent with the definition of limited data sets under the HIPAA privacy rule and contain no unencrypted patient identifiers, and thus they were considered exempt from institutional review board review. We limited the sample to adolescents ages 12–17. We identified and excluded individuals with cancer on the basis of diagnosis and procedure codes because opioid prescribing guidelines often exclude cancer. We also excluded from the Medicaid analysis those who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid because we did not have access to pharmacy claims billed to Medicare.

We identified all oral prescriptions with the dosage form of tablet or capsule filled by adolescents for the most commonly prescribed opioids: hydrocodone, hydromorphone, oxycodone, codeine, methadone, tramadol, and morphine. We did not include oral liquid forms of the commonly prescribed opiates because days’ supply for these prescriptions was not as consistent and accurate as pills. We excluded prescriptions with invalid information defined as less than one day’s supply or >365 days’ supply, quantity less than one, or quantity equals one and days’ supply >30. Combination drugs were classified according to the opioid ingredient. We measured average days’ supply per prescription by using the following categories: one, two or three, four or five, six or seven, eight to 15, 16–30, and >30 days.

Results

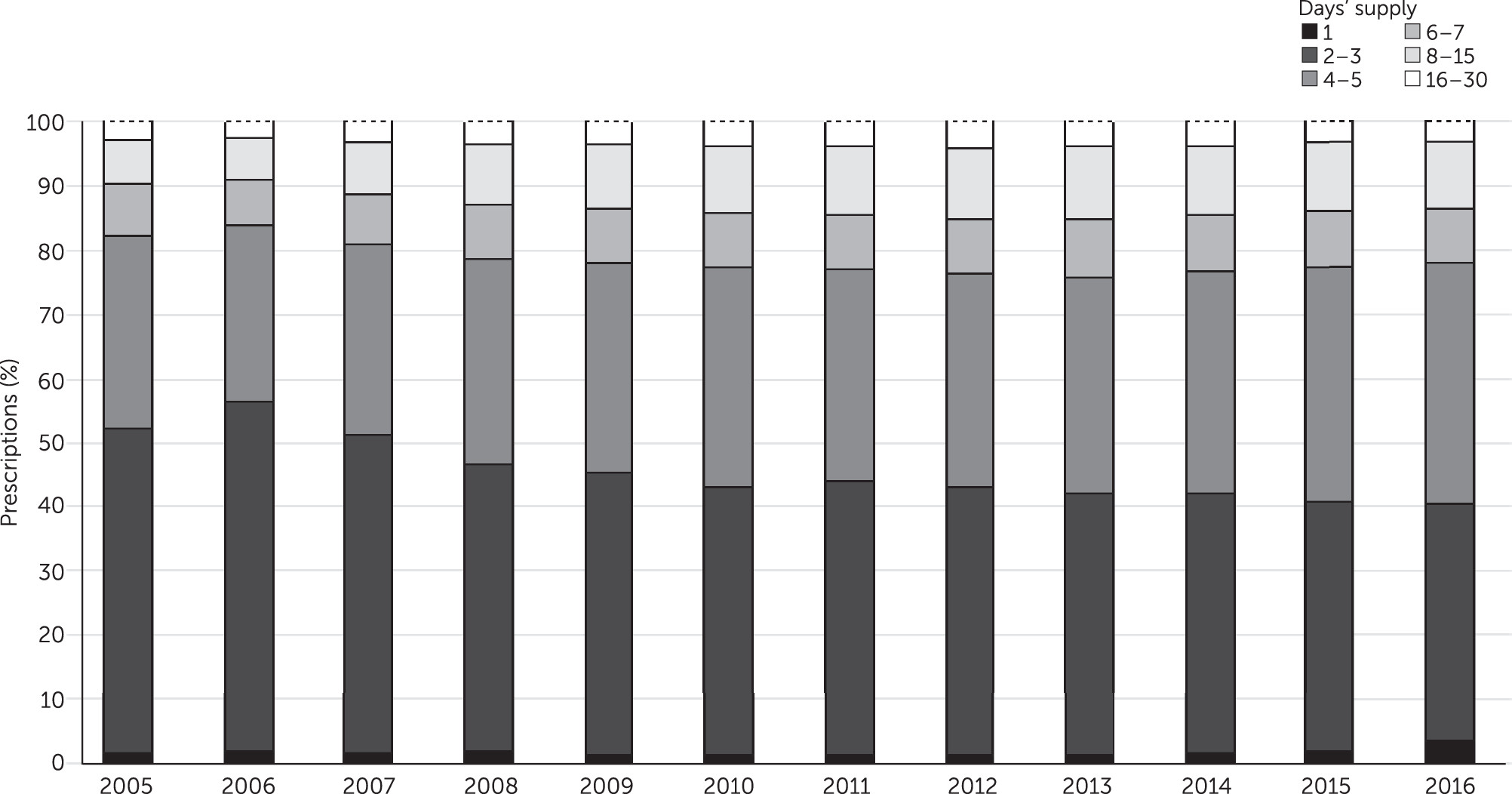

For adolescents with Medicaid insurance (

Figure 1), a supply of two or three days was the most common prescription range until 2016, decreasing from 50.5% of prescriptions filled in 2005 to 36.7% in 2016. Over the period, the percentage of prescriptions with a supply of four or five days increased from 30.2% to 37.7%. These trends mirror each other in opposite directions. Other ranges did not change greatly, with prescriptions for supplies of six or seven days and 8–15 days both increasing somewhat across the study period. Prescriptions for >30 days remained near 0%, and one-day prescriptions remained at 1.0% to 2.0% until 2016, when they increased to 3.6%. Over the 12-year period, the greatest changes occurred in the years 2005 to 2010. [A color version of Figure 1 is available in an

online supplement to this report.] Adolescents with commercial insurance received opioid prescriptions that followed very similar patterns to those for adolescents with Medicaid [see

online supplement]. The change in proportion of prescriptions in each days’ supply group between 2005 to 2016 was statistically significant (p<.001) for both Medicaid and commercial insurance [see tables in

online supplement].

Discussion

We found that in the years leading up to widespread awareness of the dangers of opioid prescribing, the days’ supply of prescribed opioids for adolescents often was higher than the three days recommended by the CDC in 2016 for adults with acute pain. The CDC did not provide explicit guidance for individuals under age 18 but did recommend that opioids be prescribed even more cautiously for adolescents than for adults (

9). Our finding that prescriptions for a supply of two or three days was decreasing while prescriptions for a supply of four or five days was increasing suggests a substitution effect. However, the uptick in one-day opioid prescriptions in 2016, the same year as the CDC guidelines, is promising and may indicate that some prescribers are increasingly trying to minimize prescribing to adolescents. The impact of recent state policies aimed at improving opioid prescribing may not be observable in our time frame. As states increasingly impose days’ supply restrictions for adolescents that are often more restrictive than those for adults (

10–

14) and as those restrictions are strictly enforced, it is possible that the increasing trend of prescribing a supply of four or five days of opioids for adolescents might reverse.

There are few studies connecting state regulations to outcomes. However, certain steps might help reduce overprescribing to adolescents and opiate misuse in this population, such as enacting laws limiting supply and mandating prescriber education that focuses on adolescent needs and on the risks associated with misuse and diversion of excess opioids. Publication of guidelines on adolescent opioid prescribing may also be valuable. Two primary prescribing venues on which to focus efforts on adolescent prescribing may be emergency departments and dental practices, because these are common sources of misused prescriptions for adolescents. Prescribers in emergency departments and dentists may not be acutely attuned to distinctions in prescribing for adolescents compared with adults.

One limitation of this study was that some adolescents included may have presented with chronic pain, and, as a result, they may have received a greater days’ supply. However, the study excluded those with cancer diagnoses. Guidelines have recently discouraged opioid prescribing for chronic pain because other forms of pain relief can be more effective and have less risk of addiction (

9). During the study time frame, however, prescribers were just beginning to weigh the risk of addiction with the benefits of opioid prescribing. Another limitation was that we could not disclose the specific states included in the Medicaid analysis to maintain client confidentiality. Examining the association between state policies restricting opioid prescribing and its impact on prescribing broadly or on specific days’ supply categories might be an important avenue for future studies.

Conclusions

The finding that the days’ supply of opioids was increasing among adolescents through 2016 is a cause of concern. The small increase in one-day fills in 2016 is promising and might be an important avenue for future studies to investigate as more recent data becomes available. Legislative policies and other public health initiatives, such as prescription drug monitoring programs, pill mill laws, and state prescribing guidelines, might continue to drive momentum toward less intense opioid prescribing practices, and future studies should directly evaluate the impact of these policy initiatives on opioid days’ supply prescribed to adolescents.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Nils Nordstrand for programming assistance.