Treatment guidelines recommend antipsychotic monotherapy as the standard of care for patients with schizophrenia and suggest that the concomitant use of two or more antipsychotics, or antipsychotic polypharmacy, be used only for patients with treatment-resistant illness after multiple trials of antipsychotics, including clozapine (

1–

3). Antipsychotic polypharmacy is considered acceptable only as a last resort because of limited evidence to support its use (

4) and concerns about an elevated risk of adverse side effects, such as extrapyramidal symptoms and cognitive impairment (

5–

7), overmedication (

8,

9), long-term safety (for example, risk of diabetes and metabolic syndromes) (

10,

11), and increased mortality (

12,

13). Additional concerns include high costs of antipsychotics, especially second-generation antipsychotics, and the negative impact of complicated drug regimens on treatment adherence (

14,

15).

Despite safety concerns and the paucity of evidence of the efficacy of antipsychotic polypharmacy, the practice is common in real-world clinical settings, with prevalence ranging from 10% to 30%, depending on definition, treatment setting, and patient population (

4). Moreover, some evidence suggests that prevalence rates may be increasing. For example, Gilmer and colleagues (

16) analyzed 1999–2004 data from Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia (N=15,962) in San Diego County and found that the yearly proportion of beneficiaries receiving second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy increased from 3.3% in 1999 to 13.7% in 2004. Clark and colleagues (

17) examined data from a cohort of 836 Medicaid enrollees with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in New Hampshire and found that antipsychotic polypharmacy increased from 5.7% in 1995 to 24.3% in 1999. Ganguly and colleagues (

18) examined trends in antipsychotic polypharmacy among outpatient Medicaid recipients in Georgia and California and found that antipsychotic polypharmacy increased from 32% in 1998 to 41% in 2000.

To the best of our knowledge no recent studies have examined trends in long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy in a Medicaid population. The few prior studies that have examined trends in antipsychotic polypharmacy have focused on short-term polypharmacy (for example, overlaps of seven, 14, or 30 days), which could reflect cross-titration (transitioning from one antipsychotic to another) rather than deliberate, long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy. Consequently, the proportion of patients receiving persistent, long-term polypharmacy is unknown. The objective of this study was to examine trends, patterns, and predictors of long-term of antipsychotic polypharmacy for a statewide Medicaid population of individuals with a schizophrenic disorder (

ICD-9-CM code 295.xx), a cluster of diagnoses that includes paranoid schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and unspecified schizophrenia. As in previous research (

19,

20), we used a conservative operational definition of polypharmacy (≥90 days) to identify the persistent long-term use of antipsychotic combinations.

Methods

Data Source

This study used Medicaid fee-for-service claims and managed care encounter data obtained from the Ohio Department of Medicaid. The database included demographic and clinical information, inpatient and outpatient utilization data, and outpatient prescription data for Medicaid enrollees. Eligibility files included information on monthly enrollment status, eligibility category (for example, covered families and children or disabled), and demographic characteristics of enrollees. Pharmacy files provided information on prescriptions filled by outpatient pharmacies, including dispense dates, generic name and code, national drug code, dosage, days’ supply, and quantity. Antipsychotic medications were identified from pharmacy files by using the dispense date and the generic name codes. The institutional and professional files provided information on service claims for inpatient hospitalizations, physician visits, and other outpatient services and included dates of service, CPT/HCPCS procedure codes, and up to seven ICD-9-CM diagnoses. All procedures were approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board.

Study Design and Sample

This observational study employed a retrospective cohort design with administrative claims data. Eligibility for inclusion in the sample was defined by two or more claims for a schizophrenic disorder (ICD-9-CM code 295.xx) between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2014, and ages 18–64. Inclusion in each yearly rate was defined by continuous enrollment in Medicaid during the year and at least one prescription for antipsychotic medication during the year. The final analytic working database included 25,062 unique individuals (N=9,211 in 2008 and N=11,500 in 2014) with 70,993 observations. [A table in an online supplement to this article provides data on the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample in 2008 and 2014.] In 2014, the mean±SD age was 45.5±12.3, and the sample included 5,987 (52.1%) males. The same year, a total of 6,746 (58.7%) individuals were white, 10,292 (89.5%) were eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability, and 6,510 (56.6%) had a diagnosis of a specific schizophrenic disorder (for example, schizophreniform disorder, disorganized schizophrenia, or paranoid schizophrenia) or unspecified schizophrenia rather than schizoaffective disorder (that is, a schizophrenic disorder with a prominent mood component).

Antipsychotic Polypharmacy

Antipsychotic polypharmacy was defined as two or more antipsychotic medications overlapping for ≥90 days at any time during the study period, with an allowable 14-day gap between prescription fills. Antipsychotics were classified as first-generation, second-generation, and clozapine. The first-generation antipsychotic medications included chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, loxapine, molindone, perphenazine, pimozide, prochlorperazine, thioridazine, thiothixene, and trifluoperazine. The second-generation antipsychotics included aripiprazole, asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Clozapine was considered to be a unique agent given that it is typically used for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Predictors of Long-Term Polypharmacy

Participants were selected for these analyses on the basis of the following criteria: long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy or antipsychotic monotherapy for ≥90 days between 2008 and 2014; continuous Medicaid enrollment for six months prior to the index prescription date of antipsychotic polypharmacy or monotherapy (referred to hereafter as the preindex period); and at least one claim for a schizophrenic disorder during the preindex period.

Predictor variables were selected on the basis of previous studies of correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy (

21). Patient characteristics included age (18–35, 36–50, and 51–64), race (white, black, and other), sex, area of residence (urban or rural), and Medicaid eligibility based on disability status (yes versus no). Clinical characteristics were identified during the six-month preindex period and included a diagnosis of schizophrenia (rather than schizoaffective disorder) (

ICD-9-CM code 295), substance use disorder (

ICD-9-CM codes 304 and 305), any psychiatric comorbidities (all other

ICD-9-CM codes 290–319), and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (

22). Also included were the number of psychotropic medication classes and outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department mental health visits during the preindex period.

Statistical Methods

Trends in demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants are described with frequencies and percentages for 2008 and 2014 [see online supplement]. Patterns of specific antipsychotic use are described by using frequencies and percentages for each year of the study. Patients could appear in the study any number of times (between one and seven times) between 2008 and 2014. Thus a generalized estimating equation (GEE) population-averaged logistic regression model was used to generate the odds of antipsychotic polypharmacy for ≥90 days for a particular year compared with the prior year. The method of fractional polynomials indicated that the relationship between antipsychotic polypharmacy for ≥90 days and continuous study year was linear. Consequently, the odds ratio (OR) between any two consecutive years is the same. Both the unadjusted and an adjusted OR (AOR) are presented, where the a priori adjustment variables in the GEE logistic regression model are age, gender, race, disabled status, type of primary schizophrenia, any substance abuse, any psychiatric comorbidity, rural versus urban, number of drug classes in the participant’s history, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, count of outpatient visits, count of inpatient visits, and count of emergency department visits. When the adjusted GEE model was run, the ORs for the categorical adjustment variables are also presented. In addition, because of the large number of observations over the seven years of the study, statistical significance was set at .01 and 99% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. All analyses were run with Stata 14.1.

Discussion

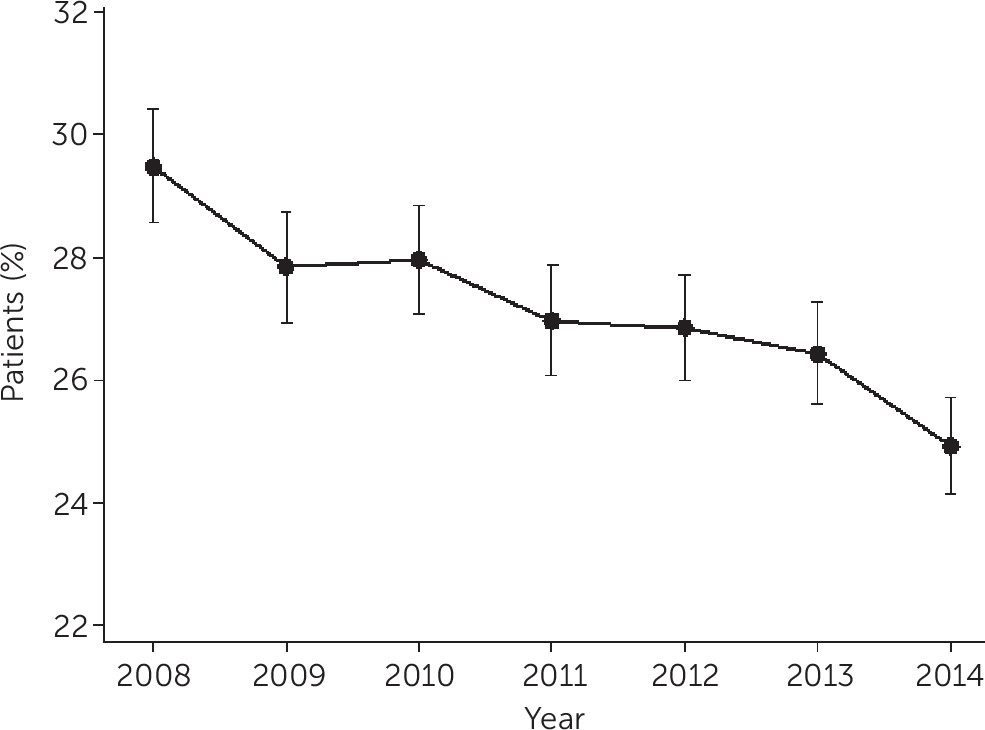

The study findings can be viewed as both encouraging and discouraging from a public health perspective. The observed significant reduction in rates of antipsychotic polypharmacy among Ohio Medicaid patients from 30% in 2008 to 25% in 2014 is encouraging, particularly because studies completed in the 1990s and early 2000s found increasing rates (

16,

18). This apparent reversal in trend suggests that the reductions in antipsychotic polypharmacy over the study period are likely a result of quality improvement efforts, such as those initiated in 2008 by the Joint Commission in cooperation with the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) and the NASMHPD Research institute. These efforts specifically targeted patients being discharged from inpatient psychiatric facilities who were receiving more than one scheduled antipsychotic (

23,

24). Growing awareness of the lack of proven effectiveness of antipsychotic polypharmacy and education to that effect may also have had some impact, although there were no formal statewide initiatives in Ohio directed toward reducing antipsychotic polypharmacy.

Our finding that rates of antipsychotic polypharmacy remained quite high is nevertheless quite discouraging; one of four pharmacologically treated patients with a schizophrenic disorder met criteria for receiving antipsychotic polypharmacy. This is troubling on several levels. First, treatment guidelines that emphasize the preferability of antipsychotic monotherapy are routinely not followed, despite considerable efforts to raise clinician awareness. Second, this finding calls attention to the reality that standard pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia are often clinically disappointing and that best practices such as clozapine monotherapy are often underutilized. Clozapine is the drug of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia because of its greater efficacy and effectiveness compared with other antipsychotics (

25–

28). Clozapine is also the only antipsychotic recommended for the management of recurrent suicidal behavior (

2,

29), which affects up to 50% of patients with schizophrenia (

30,

31). Study findings underscore the importance of efforts to optimize clozapine use among Medicaid-insured patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, given that rates of clozapine use remain low in the United States, ranging from 2% to 10% (

32).

Consistent with prior research, this study found that the likelihood of antipsychotic polypharmacy was associated with patient, illness, and treatment variables that appear related to greater illness severity (

21). This finding suggests that antipsychotic polypharmacy may be related, at least in part, to clinician and patient disappointment with standard antipsychotic monotherapy. Individuals who were younger, male, and disabled and living in rural areas were more likely to receive antipsychotic polypharmacy. Younger age and male sex may influence prescribing behaviors by virtue of their being associated with greater illness severity, poorer outcomes (

21), greater concerns about violence, and a perceived greater ability to tolerate medication-related side effects (

33). The observed positive association between antipsychotic polypharmacy and disability status is consistent with prior studies (

18,

19) and likely a proxy for severity of illness. The positive association of rural residence with antipsychotic polypharmacy is consistent with prior research suggesting that adults with serious mental illness in nonmetropolitan areas are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care and regular visits than their metropolitan counterparts (

34). Illness characteristics and treatment variables also point toward an association of antipsychotic polypharmacy with greater illness severity; polypharmacy was positively associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia rather than schizoaffective disorder; a greater number of general medical comorbidities; and use of more psychotropic medication classes, outpatient mental health treatment, and emergency room visits.

Factors associated with lower rates of antipsychotic polypharmacy included a greater number of inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, which may offer an opportunity to promote treatment guidelines advocating antipsychotic monotherapy; consolidate antipsychotic treatment; and initiate other interventions, such as clozapine or long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication. The presence of a substance abuse disorder was also associated with a lower risk of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Physicians may be less likely to prescribe a second antipsychotic to patients with substance abuse disorders because of an impression that the patient’s substance use may be contributing to the psychotic disorder and thus warrants greater attention than antipsychotic prescribing. In addition, substance abuse has been found to be associated with higher rates of medication nonadherence (

35). African Americans and persons from other racial minority groups were also less likely to receive antipsychotic polypharmacy in this study, a finding consistent with some previous investigations (

19,

36) but not others (

37). The impact of race and ethnicity on antipsychotic polypharmacy is difficult to interpret, with some studies reporting higher antipsychotic polypharmacy among white non-Latino patients (

38,

39), others finding both higher (

37) and lower rates among African Americans (

19,

36), and still others finding no significant differences across racial and ethnic groups (

33). The reason for the observed negative association between antipsychotic polypharmacy and African-American and other minority status is unclear, but it may be related to disparities in health service delivery or different cultural beliefs, perceptions, and preferences about psychiatric medications and treatments in these communities (

40). Additional research on the relationship between race-ethnicity and antipsychotic polypharmacy is warranted (

41,

42).

The strengths of this study included a large study sample, examination of long-term polypharmacy versus short-term polypharmacy, longitudinal analysis of antipsychotic polypharmacy use over time, and a wide range of predictor variables. However, several limitations need to be considered. First, because the data are from a single state Medicaid population, findings may not be generalizable to other state programs or to non-Medicaid populations. Second, our use of administrative data precluded an examination of other patient characteristics (for example, positive and negative symptoms and a history of violence) and provider characteristics (for example, specialty and clinical setting) that may be associated with polypharmacy. Third, the comparison between schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder may be biased by the change in criteria for schizoaffective disorder in DSM-5. Finally, absent more reliable diagnostic information than is available in claims data and information about treatment plans and outcomes, it was not possible to gauge the appropriateness of antipsychotic polypharmacy.