Non-Hispanic blacks are five times more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be given a diagnosis of schizophrenia and are also at a higher risk of being misdiagnosed with schizophrenia (

1–

6). In addition, compared with non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks and other racial and ethnic minority groups (for example, Hispanics) with psychotic disorders have higher rates of involuntary hospitalizations and interactions with law enforcement and are less likely to be enrolled in outpatient mental health services and adhere to treatment (

7,

8). Although the causes of these disparities are unclear, racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have limited access to care, to lack insurance coverage, and to experience implicit bias (

9,

10). Individuals from minority groups are also more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have negative opinions about mental health care and mistrust of providers (

10–

12).

Each year, an estimated 115,000 individuals experience first-episode psychosis (FEP), and 70% of FEPs occur before age 25 (

13,

14). FEP is a critical point in the initiation of mental health care for individuals, and the support of their family members is essential in the prevention of poor short- and long-term outcomes (that is, lifelong disability) associated with schizophrenia (

15). FEP interventions have been developed and tested throughout the world (

16–

18). Although these interventions differ in terms of their components, all include a combination of evidence-based interventions for psychosis, such as antipsychotic medications, case management, psychotherapy, vocational rehabilitation, and family psychoeducation. In the United States, the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode, Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP), a large multisite randomized controlled trial, investigated the efficacy of a coordinated specialty care intervention called NAVIGATE that incorporates shared decision making in family psychoeducation, individual therapy, medication management, and supported employment and education (

19,

20).

The RAISE-ETP (N=404) demonstrated that NAVIGATE participants had significantly higher quality of life and treatment retention, as well as less severe psychiatric symptoms, compared with persons with schizophrenia in treatment as usual (

20). Previous secondary analyses of data from this trial found that at study entry, non-Hispanic blacks had higher levels of disorganized thoughts and lower functioning, compared with non-Hispanic whites (

21). At treatment entry, non-Hispanic blacks were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive first-generation antipsychotic medications (for example, haloperidol) rather than second-generation antipsychotics, and Hispanics were also more likely to be prescribed risperidone (

22). These findings highlight further need to characterize and understand racial and ethnic differences among individuals with FEP.

Although these studies described racial and ethnic differences at study entry, no published research has described racial and ethnic differences in psychiatric symptoms, functioning, and use of evidenced-based interventions, such as family psychoeducation, individual therapy, and medication management, during the course of treatment. The primary purpose of this secondary data analysis was to examine racial and ethnic differences in psychiatric symptoms and service use among individuals in RAISE-ETP treatment conditions (usual community care and NAVIGATE) across a 24-month treatment period, accounting for baseline symptoms, duration of untreated psychosis, and insurance type.

Methods

Participants

This secondary data analysis used the RAISE-ETP data set obtained from the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive. The intent-to-treat sample included 404 individuals (usual community care, N=181; NAVIGATE, N=223) with diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, or psychotic or brief psychotic disorders assessed by using the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-4 Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID) (

23). Patients were recruited from community health agencies nationwide. Additional eligibility criteria included experiencing only one episode of psychosis and lifetime receipt of antipsychotic medications for six or fewer months. Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, psychotic depression, or substance-induced psychotic disorder; a current psychotic disorder caused by a medical condition; or a diagnosis of a neurological disorder, head injury, or other general medical condition that would impede treatment.

For the total sample, the mean±SD age was 23.61±5.06, and 72% (N=293) were male. Forty-three percent (N=173) were non-Hispanic white, 34% (N=139) were non-Hispanic black, 3% (N=12) were Asian, 5% (N=21) were Alaska Native/Native American, and <1% (N=1) identified as Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Eleven percent (N=45) identified as Hispanic white, 3% (N=13) identified as Hispanic black, 4% (N=15) identified as Hispanic other. Informed consent was obtained from participants over age 17, and informed assent and parental consent was provided for participants ages 15–17.

Study Intervention

NAVIGATE is a coordinated specialty care intervention comprising key services, such as medication management, family psychoeducation, and individual therapy (

20). Usual community care (the control condition) was determined by clinicians and available services at the designated site (

19). Participants completed a baseline assessment, followed by treatment provided across a 24-month study period. All assessments were performed by nonblinded research assistants or site-based personnel or blinded remote personnel with clinical experience to perform diagnostic interviews to evaluate symptoms and quality of life. Additional study details have been published elsewhere (

19,

24).

Measures

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score and scores on five PANSS subscales (negative symptoms, positive symptoms, uncontrolled hostility, disorganized thoughts, and anxiety and depression) were collected at baseline and months 6, 12, 18, and 24 to measure psychiatric symptoms during the treatment period (

25). The self-report Service User and Resource Form, collected at baseline and monthly during the 24-month treatment period, was used to assess the delivery of key services, such as medication management, family psychoeducation, and individual therapy (

20,

26,

27). Medication management was assessed by asking participants, “Were you asked to record your symptoms and side effects with your psychiatrist or nurse practitioner?” This measure was dichotomized into yes or no; responses of “don’t know” and “not prescribed medication” were classified as no. To assess individual therapy, participants answered yes or no to the following question: “Have you had individual sessions with a mental health provider who helps you work on your goals and look positively toward the future?” Family psychoeducation was assessed by an answer of yes or no to the following question: “Has your family met with a mental health provider to help them understand and address your situation?”

Control variables.

Prior to treatment entry, the duration of untreated psychosis was defined as the time between the onset of symptoms and receipt of initial treatment, assessed in weeks. At baseline, participants were asked whether they possessed private insurance, public insurance, or were uninsured/did not know, and this variable was used in the analyses as a proxy for socioeconomic status. Baseline PANSS subscale scores were used in each analysis.

Race and ethnicity.

Race was self-reported and categorized as white, black, and other (that is, Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American). Ethnicity was self-reported and dichotomized as either Hispanic or Latino (that is, Hispanic white, Hispanic black, or Hispanic other,) and non-Hispanic or non-Latino. Race and ethnicity were merged and characterized as non-Hispanic white (N=173), non-Hispanic black (N=139), Hispanic (N=73), and other (N=19).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for the intent-to-treat sample (N=404). Two separate generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used—the first among those who received usual community care and the second among those who received NAVIGATE—to examine racial and ethnic differences (non-Hispanic whites [reference group], non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and others) on the PANSS total score and subscale scores and use of medication management, individual therapy, and family psychoeducation services across the 24-month treatment period, controlling for duration of untreated psychosis, insurance type, and—for PANSS scores—the corresponding baseline PANSS subscale score. All analyses were replicated without the control variables to represent unadjusted analyses. [Tables and figures in an online supplement to this article report results of unadjusted analyses.] In both analyses, GEE used all available pairs to account for possible missing data. All analyses were conducted with SPSS 24.0, and statistical significance was set at p<.05. For continuous outcomes, unstandardized regression coefficients, means and standard deviations are presented, and odds ratios (ORs) are presented for binary outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Data on participant characteristics at baseline by treatment condition are presented in

Table 1.

Among participants who received usual community care, non-Hispanic blacks had significantly higher scores on the positive symptoms (for example, hallucinations and delusion) subscale of the PANSS (β=2.15, p=.010), the disorganized thoughts subscale (β=1.15, p=.033), and the uncontrolled hostility subscale (β=.74, p=.027), compared with non-Hispanic whites (

Table 2). Non-Hispanic black participants also had significantly lower scores than non-Hispanic white participants on the anxiety and depression symptoms subscale (β=–1.09, p=.042). For all PANSS scales, participants categorized as other had significantly higher scores on the positive symptoms subscale (β=4.56, p=.002), compared with non-Hispanic white participants. In the usual care condition, no significant differences between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white participants were found on any of the PANSS scales. Among NAVIGATE participants, no differences were found between non-Hispanic white participants and racial and ethnic minority groups on the PANSS total or subscale scores.

Table 3 presents the mean PANSS scores for usual community care and NAVIGATE treatment conditions by race and ethnicity across the 24-month treatment period. The findings were similar to those in the unadjusted model, which did not include baseline control variables (that is, duration of untreated psychosis, insurance type, and baseline PANSS scores) [see

online supplement for results of unadjusted analyses].

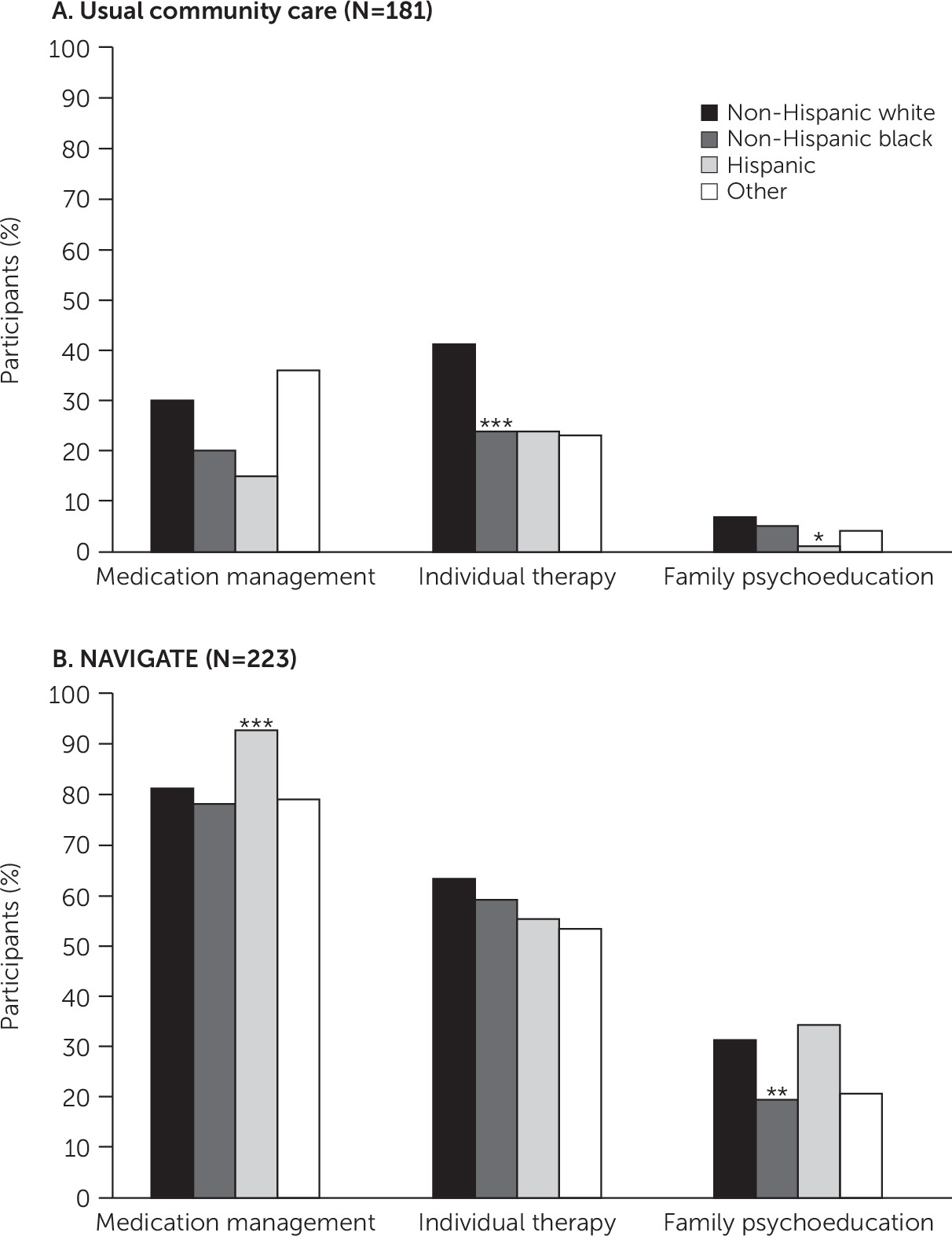

Figure 1 shows the percentages of individuals by treatment condition who received key services. Among those in usual community care, non-Hispanic blacks were significantly less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive individual therapy (OR=.45, CI=.45–.28, p=.001), and Hispanic participants and their family members were significantly less likely than non-Hispanic white participants and their families to receive family psychoeducation (OR=.20, CI=.06–.75, p=.01).

Among NAVIGATE participants, non-Hispanic blacks and their family members were significantly less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive family psychoeducation (OR=.53, CI=.32–.85, p=.009), and Hispanic participants were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic white participants to receive medication management (OR=2.93, CI=1.72–5.01, p=.001). There were no significant differences in service utilization between participants in the category of other ethnic-racial group and non-Hispanic white participants and no racial or ethnic differences at all in utilization of individual therapy.

Discussion

Among participants who received usual community care, non-Hispanic black participants experiencing FEP had significantly higher scores than non-Hispanic whites throughout the 24-month treatment period on subscales measuring positive symptoms, disorganized thoughts, and uncontrolled hostility. During treatment, participants in the category of other also had significantly higher scores on the positive symptoms subscale, compared with non-Hispanic whites. In the NAVIGATE treatment condition, no differences between racial and ethnic groups in psychiatric symptoms were noted during the treatment period. Furthermore, previous studies have suggested that the combination of components found in NAVIGATE, such as multidisciplinary teams, shared decision making, individual and family therapy, skill-based training, and modular-based treatment plans, reduces disparities that affect minority populations (

28). Although the covariates were not the focus of this study, duration of untreated psychosis was significantly associated with PANSS scores throughout the 24-month treatment period in the NAVIGATE treatment condition, which is consistent with the findings of Kane and colleagues (

20). Differences in psychiatric symptoms might not have been present in the NAVIGATE treatment condition because providers were required to implement fidelity measures, thereby standardizing treatment and ensuring consistency of treatment delivery.

The findings of our study build on previous research suggesting that non-Hispanic black patients with FEP begin treatment with more severe symptoms and a level of impairment that may limit the treatment benefit for racial and ethnic minority populations (

21). This disparity among non-Hispanic black participants, along with our findings regarding positive symptoms, disorganized thoughts, and uncontrolled hostility throughout treatment, may be influenced by various other factors, such as lack of culturally tailored treatment delivery plans and materials, limited engagement and use of mental health care, low health literacy, cultural mistrust leading to negative perceptions of the mental health care system, or misdiagnoses of symptoms (

10–

12,

29,

30). In contrast to our findings for the NAVIGATE treatment condition, non-Hispanic blacks and persons in the category of other in the usual care condition were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive evidence-based interventions, which likely contributed to racial-ethnic differences in psychiatric outcomes. This disparity could be the result of inconsistencies in quality of care and type of services received in the usual care condition. These differences also indicate the need for additional focus on addressing racial disparities in FEP treatment outcomes and the potential influence of cultural mistrust in the community mental health care setting.

Participation in NAVIGATE has been shown to be associated with improved outcomes and engagement in or receipt of key services (

20,

31). However, previous analyses of NAVIGATE data did not assess participation in key NAVIGATE services by racial-ethnic minority groups. In both the adjusted and unadjusted findings, this secondary data analysis revealed that among NAVIGATE participants, non-Hispanic blacks and those in the group categorized as other were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to engage in family psychoeducation during the 24-month treatment period. These findings suggest that family psychoeducation may not appeal, may not be consistently offered, or may not be appropriately tailored for non-Hispanic blacks and other racial and ethnic minority groups. Lower levels of family engagement are associated with poorer long-term outcomes (

32–

35). Although a considerable amount of literature has examined barriers to family engagement and family experiences among non-Hispanic blacks (

36–

42), less research has focused on understanding the benefits of culturally tailored family psychoeducation and enhancements to existing engagement strategies to address these barriers.

Although statistically significant racial and ethnic differences in psychiatric symptoms were found in the usual care condition, caution should be taken when attributing clinical significance to differences in PANSS scores throughout treatment. First, the generalizability of our findings among participants categorized as other should be considered when interpreting the differences on the positive symptoms subscale because of the small sample (N=19). Second, among non-Hispanic blacks in NAVIGATE, total PANSS scores improved by roughly 20% during treatment (adjusting for baseline scores, duration of untreated psychosis, and insurance type), which does not meet the clinically significant cutoff of 50% improvement (

43). However, previous research has found that NAVIGATE led to clinically meaningful findings overall (

20). Findings in this secondary data analysis indicated low rates (<50%) of service use in the usual care condition, and low rates of use of family psychoeducation in the NAVIAGTE condition. Although several findings were significant, it is also unclear whether the lower rates of service use over time in the usual care condition was a result of the services not being available or not being offered to participants or whether participants simply did not engage in services that were available.

For the entire sample, the attrition rate over the 24-month treatment period was approximately 50%, leading to a substantial amount of missing data. However, our choice of statistical analyses (GEE) accounted for any missing data over time by using all available pairs in the GEE analyses. It is also important to note that the attrition rate for the RAISE-ETP study is consistent with previous studies conducted among similar populations with serious mental illness (major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders) (

44,

45). Another limitation, which may be addressed in subsequent research, was the lack of a direct measure of income or class; insurance type was the best proxy for income and class available in the deidentified NAVIGATE data set.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our secondary data analyses highlight the effectiveness of NAVIGATE, compared with usual community care, as a coordinated specialty care program for improving functioning and symptoms for individuals from racial-ethnic minority groups experiencing FEP. However, the findings also highlight racial-ethnic disparities in the NAVIGATE condition in participation in family psychoeducation, resulting in lower rates of family engagement among non-Hispanic blacks and individuals from other racial and ethnic minority groups. These findings raise the possibility that standardization and consistency of care may reduce racial and ethnic disparities. Findings also suggest that among non-Hispanic blacks and individuals from other racial-ethnic minority groups, improvements are needed for culturally sensitive engagement, additional support networks, and outreach strategies targeted at families in both coordinated specialty care programs and community care settings. Identification of barriers or challenges to treatment engagement that are specific to individuals and families experiencing FEP can inform the development of culturally tailored engagement plans that will increase participation in evidence-based family psychoeducation interventions.