Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder of childhood (

1), with 9.4% of children in the United States having received an ADHD diagnosis, including approximately 388,000 children ages 2 to 5 (

2). ADHD is characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity, with symptom onset before age 12 and associated functional impairment (

3). Children with ADHD are more likely to experience negative outcomes such as injury, emergency room visits, peer problems, and dropping out of high school, compared with peers who do not have ADHD (

4–

8).

In 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published updated clinical practice guidelines for ADHD with treatment recommendations by age group (

9). Behavior therapy is recommended as the first-line treatment for preschool-age children diagnosed as having ADHD, with medication prescribed only if moderate or severe functional impairment remains. Parent-based behavior therapy interventions have been shown to reduce disruptive behavior in young children, and therapeutic effects persist after treatment completion (

10). Similar treatment recommendations are also included in clinical guidance for child psychiatrists (

11), with an emphasis on monitoring for effectiveness and adverse events when medication is prescribed for young children (

12). In addition, a recent study has shown that sequencing a behavioral intervention before initiating medication can lead to better outcomes than if medication is administered first (

13).

Despite this evidence and clinical recommendations, administrative claims data indicated that during 2008–2011, approximately 78% to 79% of preschool-age children who were enrolled in Medicaid and were receiving clinical care for ADHD received prescriptions for ADHD medication, while only about one-half received psychological treatment services (

14). However, that study took a cross-sectional approach and did not examine sequencing of treatment, specifically how many children received behavioral treatment before medication. Previous research has used Medicaid claims data to define treatment trajectories for children with mental disorders (

15,

16) but has not focused on whether treatment patterns for young children with ADHD conform to clinical guidelines.

The objective of this study was to describe longitudinal utilization of outpatient care among Medicaid-enrolled children between ages 2 to 5 with ADHD in seven southeastern states with respect to clinical recommendations. We also examined demographic and ecological factors that were associated with membership in the utilization profiles most consistent with clinical practice guidelines. States from the southeastern part of the United States were selected for analysis because this region has been shown to have a higher estimated prevalence of diagnosed ADHD than at least two other regions (

2,

17); however, previous work has shown considerable variation in estimates of ADHD treatment across states, even among states located within the same geographic region (

14,

18). The analyses presented in this study are stratified by state, informing state-level policies and programs related to young children with ADHD.

Results

This study included 53,460 children ages 2 to 5 (

Table 1). The state-level per-patient-per-year rate for treatment events varied from 12.35 (Mississippi) to 0.26 (Louisiana) for psychological services visits and from 6.50 (North Carolina) to 3.61 (Mississippi) for medication (re)fills. [Information about the distribution of children in the study population by demographic characteristics is provided in the

online supplement.]

Patient-Level Utilization Behaviors

Three utilization profiles were identified for six states, while only two unique utilization profiles were identified for North Carolina.

The identified profiles were characterized qualitatively relative to other utilization profiles in each state by using two main descriptors. High psychological services (HPS) or low psychological services (LPS) describes utilization profiles with overall high or low probability of transition into psychological service visits. Profiles without a labeled HPS or LPS designation had no transitions into psychological services with a probability of greater than 5%. High medication (HRX) or low medication (LRX) describes utilization profiles with overall high or low probability of transition into medication. For each profile, additional descriptors show event types (MHF, PO, ER, or OP) from which transitions to psychological services or medication originated with a probability of higher than 10%.

In

Table 2, the profiles for each state were grouped into four profile types by using these descriptors: group 1, HPS/LRX; group 2, LPS/LRX; group 3, LPS/HRX; group 4, HRX.

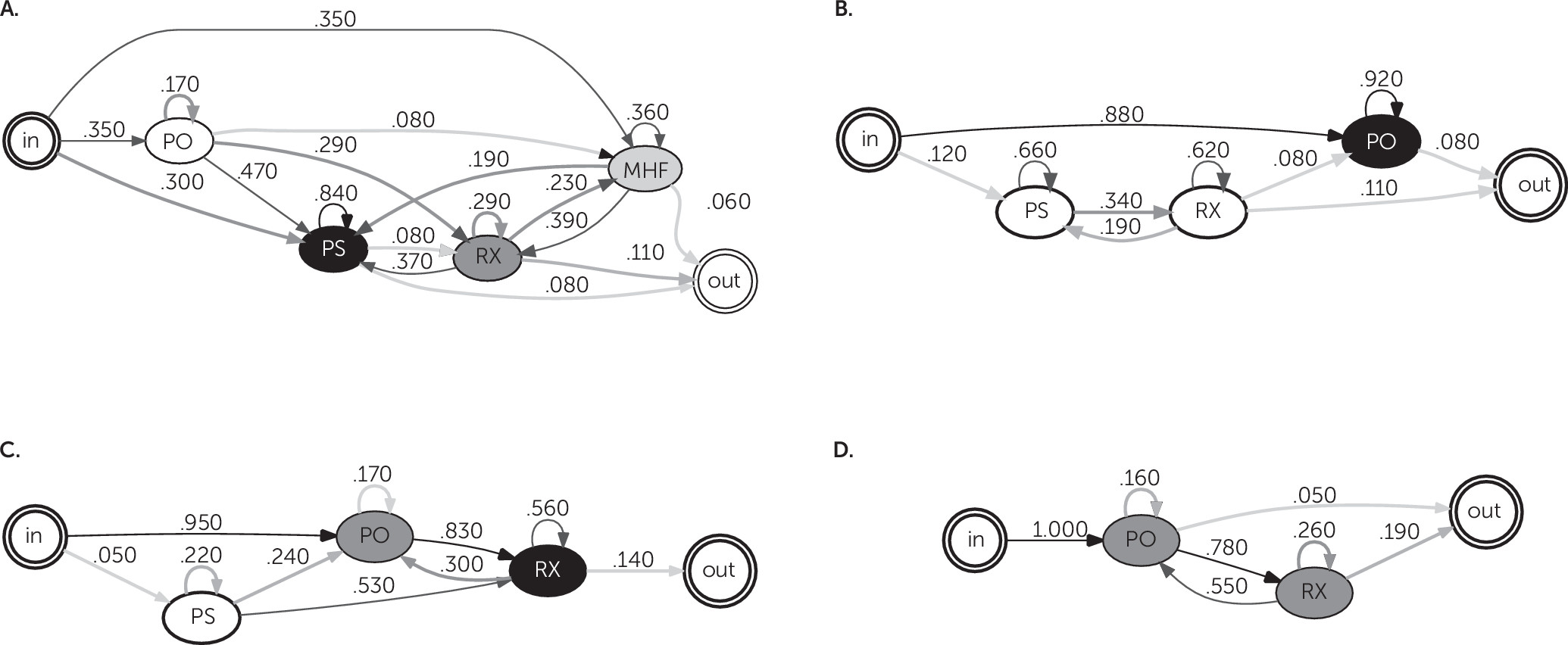

Figure 1 shows a set of four utilization profiles as examples (labeled by state and profile group number) to illustrate a profile from each group.

Table 3 presents a summary of profile characteristics for all profiles [see

online supplement for a description of all utilization profiles for each state].

The first group of profiles had a high probability of transitioning into psychological services and a low probability of medication usage (HPS/LRX); five states had a profile with this description. These profiles represented 10% (N=586) (Alabama) to 30% (N=1,169) (Mississippi) of each state-level study population and 15.5% (N=8,294) of the total study population. In these profiles, more than one-half of the children transitioned into psychological services either directly or indirectly (that is, following another ADHD-related event). Of the sequences that included psychological services in these profiles, the highest probabilities were associated with sequences in which psychological services were received before medication, consistent with AAP guidelines. These profiles also generally had a high probability of continued psychological service receipt; the probability of having additional psychological services claims after the first psychological service event more than 0.80 for each state’s profile except for South Carolina’s (0.53). The probability of children in these utilization profiles receiving ADHD medications ranged from 0.02 (Mississippi) to 0.29 (Georgia).

The second group of profiles had comparatively lower probabilities of transitions to both psychological services and medication (LPS/LRX); five states had a profile in this group, representing between 0.20 (N=2,015) (North Carolina) and 0.31 (N=1,735) (Alabama) of the study populations in those states. In those profiles, the probability of transitioning into psychological services was between 0.12 (Florida) and 0.51 (Mississippi), and the probability of transitioning into medication was between 0.04 (Florida) and 0.53(Alabama).

The remaining profile groups were characterized by relatively high probabilities of medication treatment. The third profile group had a relatively low probability of transition to psychological service utilization (between 0.02 and 0.31) and contained profiles from five states, while each profile in the fourth group had a less than 5% transition probability from any single node to any psychological services events. Each profile in these two groups had a probability of a transition to medication treatment of more than 50%. Among those that transitioned to medication, none of the profiles had a probability greater than 0.05 of then transitioning to a psychological services event, except for the South Carolina profile (0.19). These profiles represented the largest proportion of the study population overall (0.65, N=34,866) and in each state.

Variations Across Utilization Profiles

The profile with the highest probability of a transition to psychological services was selected for each state (group 1 profiles indicated in

Table 2) as the outcome of interest for the logistic regression models. Louisiana and North Carolina were excluded from the logistic regression analyses because neither had a profile with a high probability of transition to psychological services receipt.

Table 4 presents logistic regression results for each state comparing membership in the profile with the highest probability of transition to psychological services with membership in the other profiles.

In Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina, black race was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of being in a profile with a high probability of psychological services. In Florida and South Carolina, children living in areas with higher rates of poverty and higher percentages of adults with a bachelor’s degree were more likely to be in a high psychological services profile, whereas in Georgia, the percentage of adults with a bachelor’s degree was inversely associated with likelihood of being in a high psychological services profile. Children living in a rural or small urban setting in Georgia and Mississippi and children living in a rural setting in Alabama were more likely to be in a high psychological services profile than children living in a large urban setting in the same state, whereas in South Carolina, children living in a rural setting were less likely than children in large urban settings to be in a high psychological services profile.

Discussion

This study evaluated the health care utilization patterns of Medicaid-enrolled children ages 2 to 5 following a new diagnosis of ADHD and compared these utilization patterns to clinical guidance. Only about 16% of young children in Medicaid in the southeastern United States had utilization consistent with a high probability of receipt of psychological services before medication and a high probability of repeated psychological service visits after diagnosis with ADHD. This finding indicates a major gap in treatment, because clinical guidance recommends behavior therapy as the first-line treatment for ADHD in young children (

9,

11). Although these results are largely from the period before the 2011 release of the AAP guidelines, guidance for child psychiatrists reflecting the preference for behavior therapy before medication for young children with ADHD had been published earlier (2007), suggesting that treatment of young children with ADHD in the community was not always consistent with recommended best practices.

These analyses revealed state-level variation in utilization profiles for ADHD-related health care. Five states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina) had one utilization profile with a high probability of transitioning into psychological services that seemed to be consistent with pediatric clinical practice guidelines (

9,

11). Most young children receiving care for ADHD (65%) were in utilization profiles characterized by low or no probability of psychological services and high probability of receiving ADHD medication. These results are consistent with previous research that showed that less than one-half of young children received any psychosocial treatment before being treated with antipsychotic medications (

15). The variation in treatment receipt across these seven states is also consistent with previous studies showing differences in state-level estimates of medication and behavioral treatment among children with ADHD (

14,

18). We also found variation by race in the probability of being in a utilization profile most consistent with clinical guidelines. In three states, nonwhite children were more likely to be in profiles with a high probability of psychological services utilization, which corresponds with findings that nonwhite school-aged children with ADHD are more likely to have treatment initiated with psychosocial interventions than with medication alone (

28) and have less consistent utilization of medication treatment (

29). These results show that treatment for ADHD among young children varies across states and by subpopulations.

The misalignment between clinical guidance and utilization could be the result of a number of factors. Provider availability may be a key driver, because few trained professionals are available to deliver evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children (

15). There may be differences by physician type in care of children with ADHD (

30). Physicians may prescribe medication while families are placed on waiting lists for psychological services (

15,

31,

32). Providers may also be influenced by other considerations in the clinical decision-making process for initiating ADHD treatment, such as physical safety and educational concerns (

32). Although previous research found that nearly all child psychiatrists reported recommending parent training in behavior management as treatment for ADHD in preschoolers, it is unclear how many waited to prescribe medication until after parental training implementation (

33).

From the family perspective, lack of parental awareness of the availability of psychosocial treatments for ADHD can be a barrier (

32,

34). Parent preferences and beliefs may also affect the uptake of psychosocial treatment. These beliefs may include perceptions of parental self-confidence and self-efficacy to engage in these treatments, ability and commitment to prioritizing attendance at psychosocial treatment visits (

32,

34), varying levels of willingness to have their young child take psychotropic medications (

35), and level of motivation to engage in psychosocial treatments after medication treatment has been initiated (

13).

Although the profiles presented in this study provide a snapshot of ADHD-related health care utilization for young children in Medicaid in seven states, the results are subject to limitations. Because this was a longitudinal utilization study of claims data, we assessed only how often reimbursed care aligned with published guidelines. Another limitation was reliance on claims data to infer utilization. First, the MAX files only included claims that were submitted for reimbursement and did not include information on services that had no cost or were paid for outside of the Medicaid system. Second, these analyses only included children who had Medicaid claims with an indication of an ADHD diagnosis and did not include children who met the criteria for ADHD but did not have an indication of ADHD on submitted claims. Therefore, estimates of health care utilization may not be representative for subgroups susceptible to low access to care (

36,

37).

Moreover, MAX files have data quality issues (for example, missing diagnosis or procedure codes on claims, incomplete submission of claims), especially for states with large populations receiving managed care (

38). Variability in eligibility, coverage, and behavioral health carve-outs within state Medicaid programs may add to the potential differences among states; such variations are challenging to capture. Another limitation is the lack of procedure codes that specifically identify evidence-based behavior therapy for ADHD. Instead, claims related to any psychological services served as a proxy for these types of treatments. Further, this analysis did not include any behavioral interventions that were administered in primary care if an associated procedure code was not included on the outpatient claim and did not include interventions in other settings (such as preschool educational settings, parent training classes) if Medicaid was not billed for reimbursement. An additional limitation was that this analysis did not account for co-occurring conditions that may affect utilization of either type of treatment, nor did this analysis address duration of time between treatment events. The statistical regression model assumed independence among the children with a diagnosis of ADHD; however, there may be geographic dependencies that could have led to less reliable confidence intervals for the regression coefficients. Finally, the study population may not be representative of service utilization elsewhere in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julie Swann, Ph.D., and Susanna Visser, Dr.P.H., M.S., for their contributions to the initial development of this project and Matt Sanders, Richard Starr, and Paul Dietrich for assistance with data safeguards and access and the information technology infrastructure.