Early intervention services aim to provide high-quality treatment to young people in the early stages of psychosis (

1). These services have been shown to yield superior outcomes compared with regular care (

2). Although early intervention services focus on keeping patients engaged in services to facilitate clinical and functional recovery (

1,

3), disengagement from early intervention services (rates of 20%−40%) remains a concern (

4–

8). Known predictors of disengagement include racial-ethnic minority status, lack of family involvement, poor medication adherence, and substance abuse (

5,

9,

10).

Given their concern with engagement, early intervention service providers would do well to examine how they serve youths who are already disengaged from the major social systems of education and work (

11). These individuals, who are not in education, employment, or training (NEET), represent 14% of the youth population in Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries (

12) and have been a source of growing concern over the past two decades (

13–

15). Being NEET, or vocationally inactive, is associated with numerous social and economic costs, along with feeling excluded, discouraged, and disempowered (

16). The relationships between mental illness and vocational inactivity may be circular, with each increasing the risk of the other (

17–

20).

Poorer functional outcomes following treatment have been associated with higher rates of disengagement from early intervention services (

5). Individuals who are vocationally inactive are already disengaged from social systems and are economically and socially marginalized (

21,

22), which may drive their disengagement from services. This raises the yet unexplored question of whether young individuals who are vocationally inactive at entry into mental health services are more likely to disengage from treatment.

Our objective was therefore to determine if young people who were vocationally inactive (NEET) at entry into an early intervention psychosis service were likelier to disengage from treatment than their vocationally active counterparts. To understand whether prolonged periods of functional inactivity impede engagement, we also investigated the impact on future service engagement of remaining vocationally inactive following treatment. Thus, an additional objective was to examine whether those individuals who remained vocationally inactive after a year of treatment were more likely to disengage from services during the second year of treatment compared with those who started work or school during the first year of treatment.

Discussion

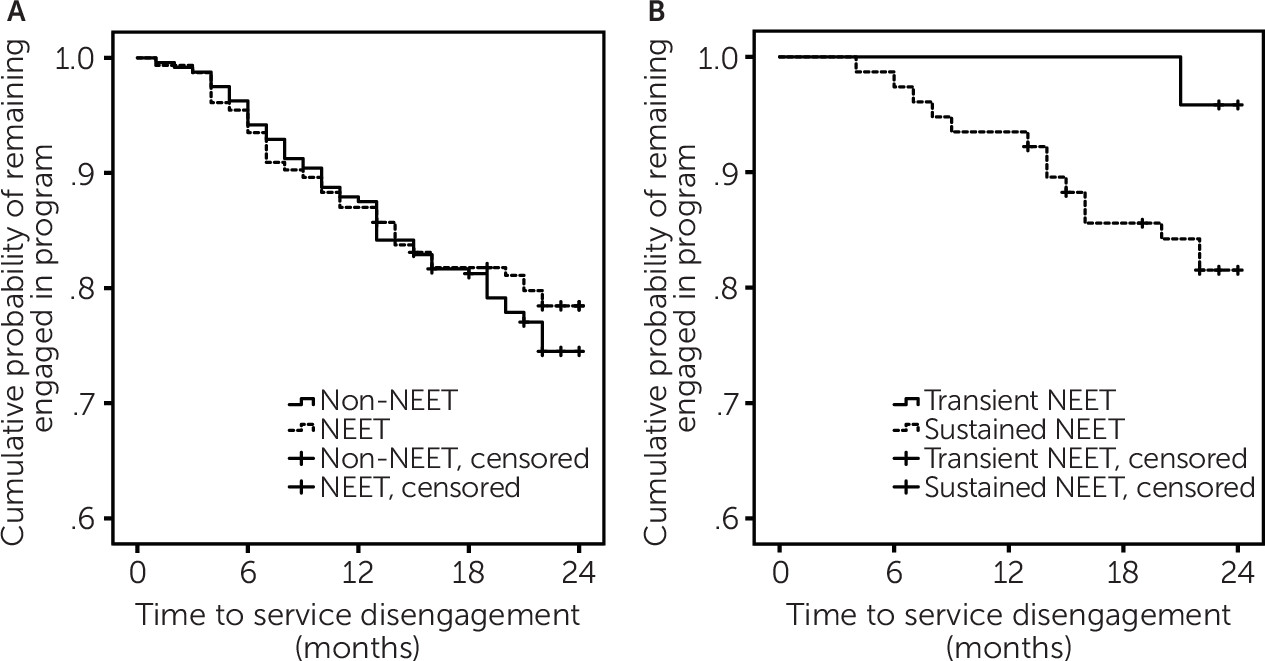

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between vocational activity status and disengagement from an early intervention service for psychosis. We found that individuals who were vocationally inactive (NEET) at baseline were at no higher risk of service disengagement over the subsequent 24 months than those who were vocationally active at baseline. However, those who remained vocationally inactive (NEET) throughout their first year in treatment had an eightfold higher risk of disengaging during the second year than those who were vocationally inactive only at baseline. Notably, all those who were vocationally inactive at month 12 were not at a higher risk for service disengagement than all those who were vocationally active at that time point.

It was not initial vocational activity status but the trajectory of work and school functioning early in treatment that was associated with eventual service engagement or disengagement. Our findings suggest that youths who remain in the “NEET trap” are doubly disadvantaged not only in suffering socioeconomic exclusion but also in missing out on the potential benefits of early intervention.

This implies that by assertively connecting young people who are not vocationally active when they enter services to meaningful education, training, or work opportunities within the first year of treatment, we could decrease their risk of service disengagement and simultaneously improve their outcomes. A relatively small proportion of patients (30%) in our service receive individual placement and support, for which there is a long waiting list.

Additionally, we had access only to data regarding the number of patients receiving individual placement and support from 2013 onwards, whereas our study cohort goes back to 2003. We were thus unable to examine if receiving this evidence-based supported employment intervention would have positively affected functioning (i.e., fewer individuals remaining vocationally inactive at 12 months) or service engagement trajectories. Nonetheless, given the strength of evidence for individual placement and support (

23,

29–

31), we recommend that it be offered as a core intervention in early psychosis services. This is also congruent with patients’ views that engagement in early psychosis services hinges on receiving help with goal setting and interventions like supported employment (

32).

At baseline, youths who were vocationally inactive (NEET) were less likely to have completed high school than those who were vocationally active. Over 60% of those who were vocationally inactive at baseline did not start work or school during the first year of treatment. Notably, those who remained vocationally inactive at 12 months were also less likely to have completed high school than those who were vocationally inactive only at baseline. Their low high school completion rates suggest that those with sustained vocational inactivity may represent a subgroup of patients whose preonset course is characterized by functional decline.

Our earlier work (

33) in this same sample indicated that compared with individuals who were vocationally active (not NEET) upon entry, those who were vocationally inactive (NEET) had longer DUPs and longer prodromes and were more likely to remain symptomatic during the period between first psychiatric change and the onset of psychosis. Both these groups had similar educational and social premorbid adjustment scores in childhood and early adolescence. In late adolescence, however, adjustment scores were significantly worse for vocationally inactive youths. Starting in late adolescence, the vocationally inactive group (NEET) thus seems to follow a distinct trajectory of persistent symptoms and functional decline leading up to a psychotic disorder, which, unfortunately, also tends to get detected much later.

Taken together, our earlier work and the present results highlight the need for earlier, broader-spectrum interventions that address youths’ educational and occupational concerns along with their mental health needs, potentially reducing the persistence of both mental health symptoms and functional decline, and for educational and occupational supports within early intervention services for psychosis to help individuals emerge from the “NEET trap” and foster their service engagement.

We cannot discount the possibility that those who have persistent difficulty engaging in school or work may in fact be the ones who also have difficulty engaging in mental health care. In other words, vocational activity status may be an indicator reflecting an intersection of other factors. For instance, at baseline, those who were vocationally inactive were likelier to be male, have poorer educational attainment, have a longer DUP, have more negative symptoms, and have a substance use disorder diagnosis. We found that some factors that underpin vocationally inactive status (gender, substance use disorder, DUP, and negative symptoms) did not contribute to service disengagement. Yet, it is likely that other factors such as childhood or social adversity that we did not assess comprehensively may drive the persistence of both vocational inactivity and service disengagement.

Given our relatively modest sample size, we focused primarily on the functioning and service engagement trajectories of those who entered our service as vocationally inactive. We did not conduct multiple comparisons (e.g., comparing persons who were vocationally inactive only at baseline, only at month 12, and at both time points) or additional follow-up analyses to examine reasons (e.g., response to treatment) for our findings. These may be critical avenues for future research with larger sample sizes. Despite this limitation, our study’s strength was that it used a previously unexplored lens—vocational trajectory while in treatment as a predictor of future engagement with services—to further the argument that some patients in early intervention services for psychosis may need vocational services and intensive case management (

34).

An additional strength was our conservative approach to classifying individuals as being vocationally inactive. We classified as vocationally inactive at baseline only those who had been out of work or school for 6 months or longer in the year before entering treatment. Thus, our study used a longer timeframe than is commonly used in the NEET literature (

15,

20,

35) to include only those facing more persistent vocational problems and not those who were vocationally inactive only immediately prior to entering treatment. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that a limitation of our study was that we are unable to describe the exact causes and onset of vocational inactivity prior to baseline. Our vocationally inactive group (NEET) at baseline may thus include those who had been vocationally inactive for a longer duration, even years, and those who were vocationally inactive for only 6 months or a year prior to entering our service.

Similarly, we classified individuals as being vocationally inactive on a sustained basis at 12 months only if they had not been in work or school for at least 6 months before entering treatment and during the first 12 months of treatment. Thus our group with sustained vocational inactivity did not include individuals who were temporarily out of work or school (e.g., taking a short break). This is in contrast to existing literature that often relies on assessments of vocational functioning at only one point in time (

12,

15,

20,

35).