In 2015, an estimated 921,580 U.S. youths ages 18 and younger were arrested (

1), and more than 31 million were under juvenile court jurisdiction (

2). Justice-involved youths have significantly greater health problems, compared with youths not involved with the justice system, including psychiatric disorders (i.e., mental and substance use disorders) (

3–

7). Between 50% and 70% of justice-involved youths meet

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders (

4,

8), a rate three to four times higher than rates in general population samples.

Despite experiencing higher rates of psychiatric disorders than youths in the general population, justice-involved youths are less likely to receive treatment (

9). Approximately 25% to 30% of justice-involved youths receive treatment while in detention (

10,

11). Even fewer receive treatment after being released (8.0%−16.4%) (

10,

12,

13). Untreated disorders increase the likelihood of adverse outcomes, including suicidality (

14) and continued contact with the justice system (

15,

16). Untreated disorders can also prevent justice-involved youths from responding to interventions to decrease criminal behavior (

17) while also increasing their risk of engaging in illicit behaviors, such as substance use (

18), which in turn increases youths’ propensity for future criminal behavior (

19).

These findings highlight the importance of early detection and linkage to psychiatric (including substance use) services for justice-involved youths. Multiple youth, caregiver, family, and system-level factors have been found to be associated with psychiatric service use among detained adolescents (

10,

13). Teplin and colleagues (

10) found lower rates of mental health service use among juvenile detainees who were from racial-ethnic minority groups, male, and over age 14. Rawal and colleagues (

20) found that black justice-involved youths had greater mental health needs, compared with white justice-involved youths, but were less likely to receive mental health treatment. Few studies have examined how caregiver factors affect justice-involved youths’ use of services; however, one study of first-time juvenile offenders reported an association between higher levels of family communication problems and mental health service use (

21). In a general sample of adolescents, significant predictors of mental health treatment engagement were family poverty, caregiver and family stress, effectiveness of parental discipline, and family cohesion (

22).

Little is known about the prevalence and determinants of psychiatric service use among justice-involved youths who are community supervised. This knowledge is important given that 75% of delinquent juveniles are diverted from detention and supervised in the community (

2). Understanding the determinants of psychiatric service use by this subgroup of justice-involved youths, particularly first-time offenders, could inform efforts to ensure identification of mental health needs and linkage to appropriate services at one of the earliest points of justice involvement.

The purpose of this study was to identify psychiatric treatment need among community-supervised youths who were first-time offenders, the prevalence and determinants of psychiatric service use, and barriers to service use. On the basis of prior studies among justice-involved youths and youths in the general population, we hypothesized that the following factors would be associated with lower rates of psychiatric service use: characteristics of youths, caregivers, and families, such as racial-ethnic minority status; greater psychiatric symptoms (of youths or caregivers); and worse family functioning.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This cross-sectional study used baseline data collected from 2014 to 2016 as part of Project EPICC (Epidemiological Project Involving Children in the Court), a two-year longitudinal study of 423 community-supervised youth-caregiver dyads. As detailed elsewhere, youth-caregiver dyads were recruited from a large, northeastern juvenile court (

23). The sampling frame included all youths ages 12 to 18 with a first-time offense. Girls with a delinquent first-time offense were oversampled to ensure sufficient power to conduct sex-based subgroup analyses.

Caregivers were notified about the study through a letter sent prior to the first court-related appointment. Prospective youths and families were approached in the court by a trained research assistant, and those who expressed interest in participating were screened for eligibility. Eligible youths were between the ages of 12 and 18 at the time of initial court contact and had an involved caregiver willing to participate in the study. After informed consent and assent, youth-caregiver dyads completed baseline assessments via an audio computer-assisted self-interview. All participants received a $50 gift card for their participation. Study protocols were approved by the principal investigator’s university and collaborating sites’ institutional review boards.

Variables

Anderson’s behavioral model of health services utilization guided the selection of factors potentially associated with use of psychiatric services by community-supervised youths, the dependent variable in this study (

24,

25). Although not specific to justice-involved populations, this model includes the broadest range of individual and systems-level factors potentially associated with health service use. Factors are categorized as predisposing (e.g., demographic factors and health beliefs), enabling (e.g., income, insurance coverage, and availability of and access to health services), and need based (e.g., psychiatric symptoms). A recently developed model that is specific to justice-involved youths is the Juvenile Justice Behavioral Health Services Cascade (

26); however, this model focuses only on substance use treatment services and does not incorporate individual or family factors (only organizational and systems-level factors).

Data for all study variables were from caregiver self-report.

Youth Characteristics

Variables for youths included age, sex, race (white; black, African American, Haitian; Asian; American Indian; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; other; or multiracial), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latinx), father or mother figure in the house, insurance coverage, primary care provider, and academic functioning (special education classes and Individualized Education Plan). Consistent with prior research (

27), race and ethnicity were combined to create a single variable with the following categories: non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic other (included Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or other nonspecified race), non-Hispanic multiracial, and Hispanic.

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed with the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition, Parent Rating Scale–Adolescent (BASC-2 PRS-A) (

28), a standardized tool for assessing risk of behavioral and emotional problems among youths ages 12 to 17. T scores are provided for nine clinical and six adaptive scales (median α=0.85; range 0.72–0.88). The BASC-2 PRS-A also includes composite scales for externalizing problems (hyperactivity, aggression, and conduct problems) and internalizing problems (anxiety, depression, and somatization). For these scales, T scores of 20–60 suggest a normal level of risk, scores of 61–70 suggest an elevated level, and scores of ≥71 suggest an extremely elevated or clinically significant level (

29). For this study, T scores of ≥71 on the externalizing or internalizing problems scale indicated clinically significant psychiatric symptoms.

Caregiver Characteristics

Variables for caregivers included age, sex, education level, marital status, employment status, disability status, receipt of public assistance, country of birth, race (same categories as for youths), and Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity. As described for youths, race and ethnicity variables were combined to create a single variable with the following categories: non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic other, non-Hispanic multiracial, and Hispanic.

Caregiver history of a psychiatric diagnosis was assessed with the following items: Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have a psychiatric diagnosis? Have you ever received treatment for drug or alcohol problems?

Caregiver-adolescent communication was assessed with the 25-item Parent-Adolescent General Communication Scale (PAC) (

30). The PAC consists of two subscales: positive aspects and negative aspects of communication. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher positive aspects scores indicate more positive communication, and higher negative aspects scores indicate more negative communication. In the study sample, each subscale demonstrated moderate internal consistency (negative aspects, α=0.76; positive aspects, α=0.81).

Family Characteristics

Variables for families included annual household income, family size, and family functioning. Caregivers’ perception of family functioning was assessed with the general family functioning scale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) (

31). This scale consists of 12 items about family communication and support. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, with responses ranging from 1, strongly agree, to 4, strongly disagree. Higher mean scores indicate better family functioning. Adequate reliability (α=0.88) has been established in prior studies of community-supervised justice-involved youths (

32). For the sample in this study, internal consistency for the FAD general functioning scale was α=0.90.

Use of Psychiatric Services by Youths

The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA) is used to assess use of psychiatric services by youths ages 8 to 18 (

33). Using criteria established by Burke et al. (

21), use of psychiatric services included endorsement of any of the following items in the past 4 months: use of psychiatric medications or receipt of care from any of the following settings and providers: psychiatric inpatient unit, inpatient alcohol or drug treatment unit or detoxification unit, day hospital or partial hospitalization, outpatient drug or alcohol clinic, mental health center for psychiatric or mental health problems, private professional help from a psychiatrist or psychologist, or private professional help from a social worker or psychiatric nurse.

Barriers to Use of Psychiatric Services by Youths

Barriers to use of psychiatric services by youths were assessed with items from the CASA (

33). Caregivers were asked about 12 different barriers to obtaining services for their child in the past 4 months, ranging from stigma (e.g., anticipation of negative reaction by family, friends, or others); concerns about cost, transportation, or language and agency hurdles. Agency hurdles included obstacles such as bureaucratic delay (waiting lists and paperwork), refusal to treat, or unavailability of the desired treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics, including means and percentages, were used to describe youth, caregiver, and family characteristics for the total sample. Bivariate analyses, including t tests and chi-square tests, were conducted to compare these characteristics among youths with and without psychiatric service use in the past 4 months. The relationship between service use and characteristics was assessed by using multivariable logistic regression. Characteristics that were significantly associated (p<0.05) with service use in the bivariate analyses and not highly correlated (p<0.5) with other characteristics were included in the multivariable model. All analyses were conducted by using Stata, version 15.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 423 youth-caregiver dyads. As shown in

Table 1, slightly more than half of youths were male (53%), and the mean age was 14.6. Thirty percent were non-Hispanic white, 8% were non-Hispanic black, 4% were non-Hispanic other, 15% were non-Hispanic multiracial, and 43% were Hispanic. Most (94%) were insured (Medicaid) and had a primary care provider (91%). In the past 4 months, nearly half of youths (49%) experienced clinically significant psychiatric symptoms.

Caregivers were predominantly female (87%), with a mean age of 41.1. Forty-two percent were non-Hispanic white, and 35% were Hispanic. Forty-five percent had three or more children, 65% were receiving public assistance, and 71% completed at least high school. Almost one-third (32%) reported a history of a psychiatric diagnosis.

Prevalence and Determinants of Youths’ Use of Psychiatric Services

Table 2 displays rates of psychiatric service use by youth, caregiver, and family characteristic. In the past 4 months, 36% of youths had received psychiatric services. A significantly higher proportion of youths with psychiatric symptoms used services, compared with those without symptoms (54% versus 18%, p<0.001). Youths whose caregiver reported a history of a psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to use services, compared with youths whose caregiver did not report such a history (59% versus 25%, p<0.001). Caregiver race-ethnicity of Non-Hispanic black and of non-Hispanic other were associated with the lowest rates of service use (14% and 12%, respectively); however, the number of caregivers from these racial-ethnic groups was small (N=5 and N=3, respectively). A higher percentage of youths from families with one child used services, compared with youths from larger families. Youths from families with lower family functioning (mean score <3; possible total scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating better functioning) were significantly more likely to use services, compared with youths from higher-functioning families. Poor caregiver-adolescent communication (i.e., higher negative communication and lower positive communication subscale scores) was associated with greater service use.

Table 3 presents data on the multivariable associations between youths’ psychiatric service use and sample characteristics. Youths’ psychiatric symptoms were positively associated with the odds of service use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=3.79), as was caregiver history of psychiatric diagnosis (AOR=3.40). Youths of caregivers who identified as non-Hispanic other were significantly less likely to have used services, compared with youths of non-Hispanic white caregivers (AOR=0.22). None of the other caregiver race-ethnicity categories were associated with youths’ service use. Neither caregiver-adolescent communication nor general family functioning scores were significantly associated with the odds of youths’ service use after adjustment for potential confounders.

Barriers to Use of Psychiatric Services

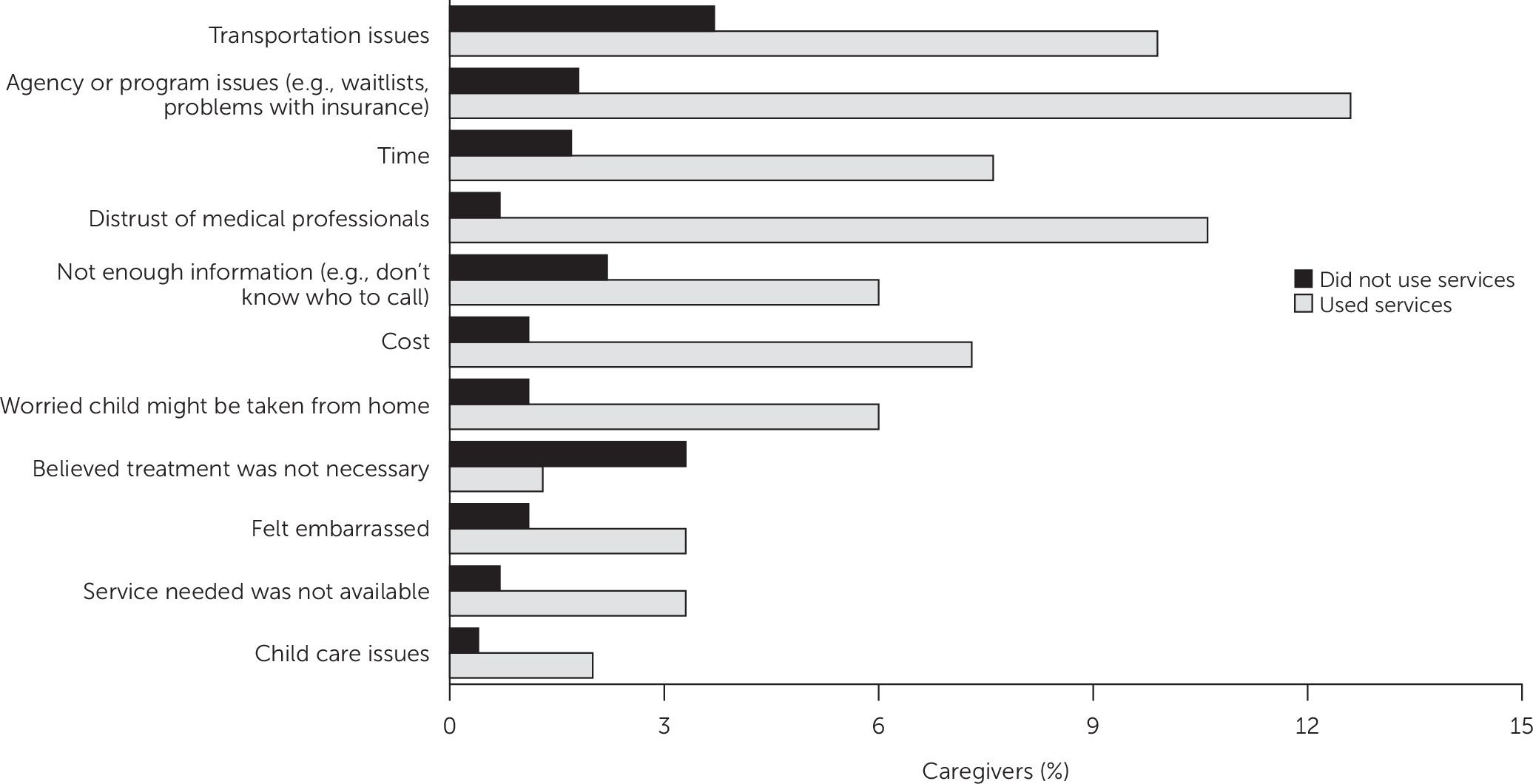

Twenty-one percent (N=87) of caregivers encountered one or more barriers to accessing services for their adolescent, and each individual barrier was endorsed by less than 10% of the total sample. (A table in an online supplement to this article presents detailed data on barriers reported by caregivers.) The most commonly reported barrier was transportation issues (6%, N=25), followed by agency or program issues (6%, N=24), time (4%, N=18), and distrust of professionals (4%, N=18). Caregivers of youths who had received psychiatric services were significantly more likely to experience barriers, compared with caregivers of youths who had not received services (35% versus 13%, p<0.001).

Figure 1 shows barriers encountered by caregivers while trying to access psychiatric services for youths. The frequency with which each barrier was reported differed according to whether the youths did (N=151) or did not (N=272) receive services. The most common barriers reported by caregivers of youths who had received services were agency or program issues (13%, N=19) and distrust of professionals (11%, N=16). Among youths who had not received services, the top barriers were transportation issues (4%, N=10) and a belief that treatment was not necessary (3%, N=9).

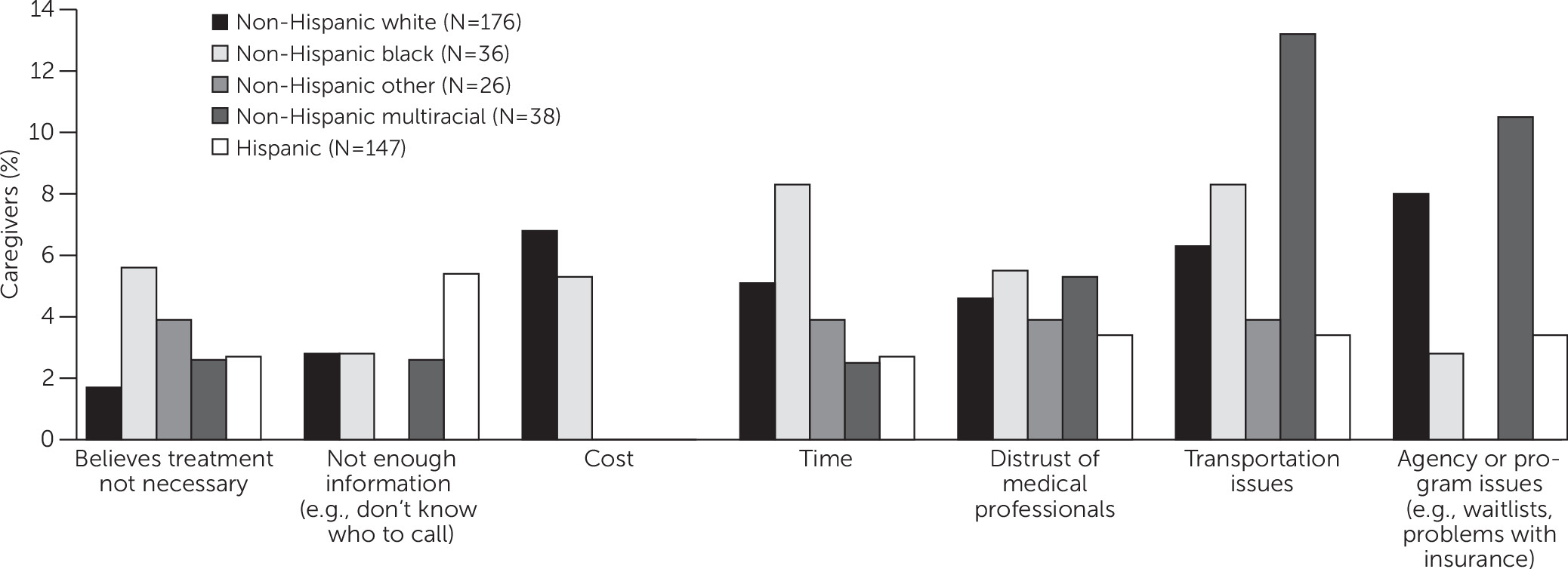

Barriers to youths’ psychiatric services were not significantly related to caregiver race-ethnicity. However, racial-ethnic group differences were observed in the frequency with which each barrier was reported. As shown in

Figure 2, the most frequently endorsed barrier among non-Hispanic white caregivers (N=176) was agency or program issues (8%, N=14). Among non-Hispanic black caregivers (N=36), the most frequently endorsed issues were transportation and time (8% for both, N=3). Among Hispanic/Latinx caregivers (N=147), the most frequently endorsed was “not enough information” (5%, N=15).

Discussion

Previous psychiatric services research among justice-involved youths has focused predominantly on detained adolescents. This study adds to the literature examining the prevalence and correlates of psychiatric service use in a large sample of community-supervised youths (N=423). The rate of service use was low (36%) in this population, despite a high prevalence of clinically significant psychiatric symptoms (49%). These results are consistent with those of a prior study showing that 74% of first-time juvenile offenders had a psychiatric disorder, yet only 20% had received mental health services (

21). A study of mental health treatment rates among previously detained adolescents showed that 82% needed treatment, but only 16% received it after community reentry (

13).

The strongest predictors of psychiatric service use were youths’ psychiatric symptoms, as assessed by the BASC-2 PRS-A, and caregivers’ history of a psychiatric diagnosis. Findings are consistent with those of previous research demonstrating that symptom severity (

34,

35) and meeting diagnostic threshold criteria (

36) were the most significant predictors of psychiatric service use among adolescents. Caregivers’ psychopathology may also positively influence youths’ use of mental health services (

37,

38). Caregivers who have personally experienced a mental disorder or who have used mental health services may be more likely to bring their children for treatment (

38,

39).

The quality of caregiver-adolescent communication and family functioning was not associated with youths’ service use, even though some research has demonstrated that youths from families with poor relationship dynamics were more likely to seek out mental health treatment (

22,

40). However, prior studies are few, and findings are inconsistent (

41,

42). Given that youths’ access to psychiatric services is often dependent on caregivers’ support and involvement (e.g., health insurance and transportation), future research should elucidate how family factors positively or negatively affect youths’ engagement in services.

Results suggest that youths whose caregiver identified as being from a racial-ethnic minority group may be less likely to receive psychiatric services, compared with youths whose caregiver identified as non-Hispanic white. More research is needed among community-supervised youths and families to understand how caregivers’ race-ethnicity influences youths’ service use in the presence of other factors. Potential explanations are that caregivers from racial-ethnic minority groups are less likely than white caregivers to identify when their child’s problem requires treatment and to initiate treatment once a problem is identified (

43,

44); uncertainty about treatment benefits (

45); less knowledge about treatment options (

44); and other perceived barriers, such as cost, lack of choices in types of services offered, and having to travel too far (

46).

Barriers to youths’ service use differed according to whether youths had received services. More caregivers of youths who used services reported barriers, compared with caregivers of youths who had not used services, primarily because of higher endorsement of barriers related to the services themselves. Such service-related barriers (e.g., agency problems) were more common among youths who had received services, whereas barriers to engagement (e.g., perceived need for treatment and transportation difficulties) were more common among youths who had not received services. These findings suggest that interventions to reduce barriers should be tailored to the stage of service use, such as help seeking or treatment engagement (

26).

Several limitations are worth noting. Data were cross-sectional and thus preclude any causal inferences. The study was also not designed to gather in-depth information about barriers to service use and thus may have missed additional important barriers. The focus on caregivers’ self-report data may have missed certain factors specific to youths’ perceptions. However, research suggests that caregivers may be better able than youths to discern psychiatric symptoms and severity (

47,

48), and caregivers’ recognition of symptoms and perceived need for treatment have been shown to be correlated with youths’ service use (

21,

49,

50). In addition, caregiver-perceived burden is known to play a significant role in youths’ ability to access health services, because youths are often reliant on their parents to take them to appointments and remain engaged in treatment (

22,

51,

52). Caregivers’ own psychological state at the time of reporting (i.e., during the youths’ first justice involvement) may have influenced their perception of their adolescent’s psychiatric symptoms; however, the rate of psychiatric symptoms in this sample is comparable to those in other studies of justice-involved youths. The low rates of use of substance use services also precluded separate analysis from mental health service use. Finally, generalizability to other community-supervised youths and families may be limited because the study was conducted in a single state, females were overrepresented, and most of the sample had public insurance. Also, the participation rate was low (28%), and potential differences between participants and those who declined were unmeasurable. Despite low participation, the study’s sampling approach likely resulted in a sample that is larger and more representative than samples in other services-related studies that included youths who were first-time offenders (fewer than 100 participants) (

21,

53).

Conclusions

There is a critical need to better understand the factors that influence use of psychiatric services by community-supervised youths, given the high rate of unmet treatment need, particularly among youths from racially and ethnically diverse families. Study findings also highlight the importance of considering caregiver factors when designing interventions to improve engagement of community-supervised youths in psychiatric services, including caregivers’ perspectives on barriers to accessing these services for their children. Obtaining this information during initial assessment for treatment needs may help the justice system connect youths to services that match their needs and preferences.