Rates of prescribing antipsychotic medications to children and adolescents remain high (

1,

2), despite guidelines against their use for behavioral symptoms of childhood mental disorders in the absence of approved indications (

3). Most antipsychotic use in youths is for nonpsychotic conditions (e.g., attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, disruptive behavior) (

2,

4). Side effects can be severe and affect patients differently (

5,

6). Lack of timely access to evidence-based psychotherapies leads to substitution with medication. For example, less than half of youths initiating an antipsychotic medication received psychosocial treatment in the previous 90 days (

7). We need to improve the quality of prescribing and care received by youths.

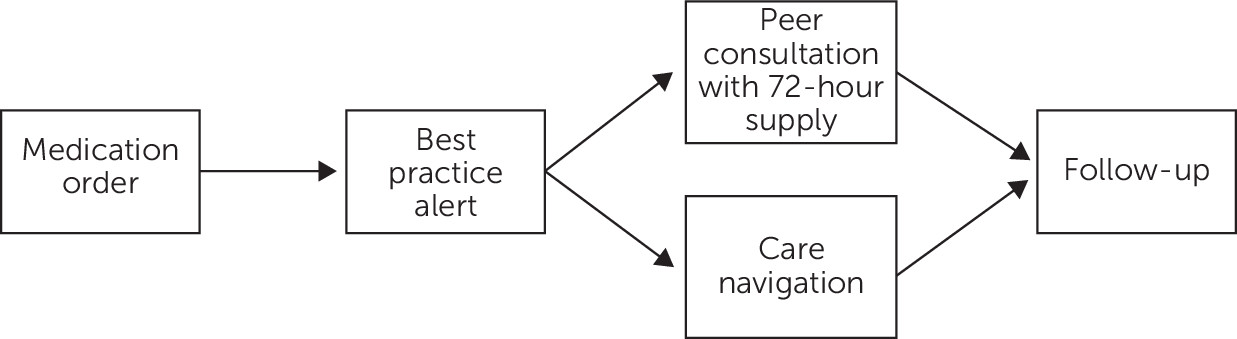

To enhance guideline-based prescribing for youths, the Safer Use of Antipsychotics in Youth (SUAY) project is testing an algorithm-based workflow in a multisite pragmatic effectiveness trial. Developed by a national consensus panel of child and adolescent psychiatrists and developmental pediatricians, the proposed SUAY workflow (

Figure 1) triggers peer consultation and care navigation, with expedited psychotherapy access for youths who have antipsychotic medication orders for nonpsychotic disorders. A related program in Washington requiring mandatory prescription review reduced antipsychotic use by half (

8). However, the program’s “hard stops” on pharmacy refills is cumbersome for clinicians. SUAY seeks to streamline this workflow.

Although technology can guide evidence-based prescribing (

9), best practices for designing effective decision support are limited (

10). Without meeting the needs of users, technology risks poor adoption, limited clinical integration and effectiveness, and unintended healthcare consequences (

11). To optimize the proposed workflow, we engaged providers in human-centered design for input on guideline-based prescribing. Human-centered design is an informatics framework for optimizing information systems and services with formative input from health care stakeholders to produce useful technology that engenders adoption (

12). SUAY “users” are prescribing providers who will incorporate the proposed workflow in their future practice.

Methods

We interviewed pediatric and adolescent providers to assess fit of the proposed workflow with their prescribing needs and practices. We recruited primary care providers, developmental behavioral pediatricians, advanced registered nurse practitioners, and psychiatrists with experience prescribing antipsychotics from Kaiser Permanente Washington and Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Kaiser Permanente Washington’s integrated health care system treats approximately 56,000 youths with behavioral health services. Nationwide Children’s Hospital treats approximately 31,000 youths annually with inpatient and outpatient behavioral health services. Both sites use the EpicCare electronic health record.

We conducted 1-hour audio-recorded interviews following a three-part guide: prescribing needs and barriers, elicited through critical incidents (

13) by recounting prior prescribing experiences; design preferences for the proposed workflow, visually depicted with a storyboard (

14) that we walked through using vignettes of fictitious patients for feedback across various clinical scenarios; and a demographic survey (see Appendix 1, which is available as an

online supplement to this report). Institutional review board approval deemed study procedures exempt. Participants received $100.

We analyzed survey data with descriptive statistics and used thematic analysis (

15) to qualitatively code interview recordings for themes about workflow barriers and design opportunities. Following Braun and Clarke (

15), we first explored patterns across interviews. Subsequent coding focused on workflow reactions to alert-guided prescribing, considerations for peer consultation (e.g., timing), and characteristics of care navigation, from which themes emerged.

Results

Fifteen participants completed interviews, including six providers from Kaiser Permanente Washington and nine providers from Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Appendix 2 (see online supplement) summarizes participant characteristics.

Participants found value in standardizing antipsychotic prescribing. Several have unfettered access to expert consultants through call services, curbside meetings, preceptors, and other informal channels, so the proposed workflow was seen as potentially duplicative. However, the workflow was considered beneficial for formalizing consultative practices in the electronic health record. Most participants recognized added benefits of care navigation but felt it was not appropriate for every case. Despite these positive reactions, providers expressed two major barriers of the proposed workflow: potential disruptions to clinical practice and threats to professional autonomy.

First, real-time consultation, hard stops, and other features of the proposed workflow led to a concern about disrupting clinical practice by reducing care quality and causing delays and safety risks. Most participants were concerned about limited time to “squeeze” real-time consultation into packed schedules. Real-time consultation was not found practical nor necessary. Some felt that rushing the consultation could provide a “disservice” by limiting time for information gathering and thoughtful discussion. A couple of participants described alternative emergency services already in place for real-time consultation. There was consensus that a thorough and thoughtful consultation, which might require time outside of patient visits, was more important than efficiency.

Enforcing a hard stop for every antipsychotic order until documentation of the consultation also raised concern about care delays and safety, such as for immediate or emergency access to antipsychotics. As one participant commented, “So my concern would be, here I am I have done a thorough evaluation and this is well within my area of expertise and my only choice is an emergency prescription and I can’t reorder it until I consult with someone and document that was done—it’s extra steps, it’s extra time and it could be a delay in treatment.”

Others described needing to start or wean patients off antipsychotics to “bridge care” while waiting for therapy or specialty care. Although participants agreed emergency prescriptions help, they found 72 hours insufficient without override options when wait times are weeks to months. Consultation with a 14-day emergency prescription was seen as reasonable, depending on the urgency of the case and consultant availability.

We identified threats to professional autonomy as the second major barrier. Behavioral health providers with extensive prescribing experience shared concern about a blanket requirement for peer consultation, describing it as “aggravating,” “scrutinizing,” or even “offensive.” They saw little value in consultation for what was perceived as reasonable prescribing by experts with training in psychiatry and pediatrics. In contrast, primary care providers considered peer consultation “reassuring,” a “safety net” for inexperienced prescribers, and a resource rather than a barrier. As one participant noted, “Nobody likes to be told what to do, but everyone likes to be offered help!” A couple of primary care providers felt the workflow implicitly encouraged them to manage complex cases they would otherwise “punt” to psychiatry. Some felt the proposed workflow should provide a “happy medium” between monitoring and guiding practice given diversity in provider experience and patient cases. Rather than treating all providers the same (i.e., alert fires for all medication orders irrespective of clinical context), some participants suggested targeting peer consultation to those who most need it.

To address these barriers, participants suggested improvements, including training, information flows, and checklists to guide prescribing. One participant suggested design improvements to reduce disruptions, saying, “What if the workflow helped guide providers to consultation by making it easy to do the right thing, such as embedding the [consultation] referral in the alert and having a place for me to enter my phone number and best times for the consultant to call me?”

Another participant recommended prereview to flag only orders outside of guideline that require consultation: “Have the prescriber write up the plan. The consultant reviews and ok’s without needing a phone discussion except for the questionable cases.” Encouraging autonomy was also suggested: “[Design it] On the honor system, for people who don’t have that expertise, to encourage them to seek a consultation, especially if it is something they have not dealt with before and particularly if it is a behavioral health issue and they are not a behavioral health provider.”

Documentation from the consultant was valued for more than only a “yes” or “no” judgment, but rather a plan for management, expectations, next steps, and patient education. Given participants’ input, we identified three consistent design opportunities to optimize SUAY workflow: provide à la carte order sets in the alert to tailor available resources to varied needs, facilitate passive review of orders to minimize disruptions and target behavior change, and encourage self-acknowledgment of completed consultation to preserve professional autonomy (Appendix 3 in the online supplement).

Discussion

Using human-centered design, we solicited provider input to optimize SUAY workflow. Interviews identified two major barriers—clinical practice disruptions and threats to professional autonomy—that can be addressed through design improvements that providers recommended: à la carte orders, passive review, and self-acknowledgment of completed consultations. Because they are grounded in the needs and practices of future intervention users, these optimizations could improve adoption and effective use. We implemented these improvements for our multisite pragmatic trial.

Findings, based on interviews with a small number of providers focused on a specific prescribing scenario, have limited generalizability and may not fully translate to other clinical settings. Although we engaged prescribers from two health care systems, findings could reflect selection bias. Future work should further compare needs of behavioral health and primary care providers. Successful adoption of workflow optimization technology requires additional research to align system design with input from a larger sample of providers, staff, and patients. Despite these limitations, findings provide insight into complex clinical workflows and professional autonomy, which are valuable for implementing SUAY and guiding development of similar interventions.

Human-centered design offers an innovative approach to improve guideline-based prescribing. Providers’ input, which reflects the needs and preferences of future users, helped us arrive at a more acceptable solution with increased likelihood of adoption. Our work illustrates a structured process for negotiating difficult design choices in which systemwide charges and individual priorities may conflict. Human-centered design helped us engage providers in the formative design of our future system that will positively impact their work.