Female veterans, like their male counterparts, are at risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and substance use disorders (

1,

2). This heightened risk may be at least partially explained by the fact that female veterans have increased exposure to combat in recent military conflicts (

3) and are at risk of experiencing military sexual trauma and intimate partner violence (

4,

5), both of which are known to increase the likelihood of mental health problems (

6,

7). These trauma exposures and related mental health problems are also strongly associated with suicide risk, a major public health concern for both female and male veterans (

8).

However, like men, many female veterans who would benefit from care do not access mental health services (

9–

11). Several unique barriers to women’s use of health care services have been identified, including lack of sensitivity to gender-specific needs on the part of some providers (

12) and lack of knowledge or misperceptions among some female veterans regarding their eligibility for, and access to, health care (

13,

14). However, one of the most significant barriers to mental health treatment is stigma.

Mental health stigma is multidimensional, and it includes mechanisms such as anticipated, internalized, and experienced stigma (

15–

18). Mental health stigma can also be broken down into stigma related to mental health problems and stigma related to treatment seeking. Prior studies that have examined veterans’ internalization of treatment-seeking stigma have revealed some notable gender differences (

19,

20), underscoring the importance of addressing stigma’s impact on outcomes separately for female veterans (e.g.,

19). The importance of examining female veterans’ experiences of stigma, and the consequences of stigma, separately from those of male veterans is further highlighted by the possibility that military cultural norms that promote masculinity and devalue femininity (

21), as well as concerns about being perceived as less deserving of care for not being “real combat” veterans (

16), may complicate female veterans’ service use.

Although several studies have documented the negative impact of treatment-seeking stigma on treatment seeking among female veterans (

17,

19,

22), the mechanisms that explain how treatment-seeking stigma affects help seeking in female veterans remain poorly characterized, in part because of the lack of longitudinal research on these relationships (

15,

18). One potential mechanism through which treatment-seeking stigma is theorized to affect service use is through its impact on perceived need for mental health care. The health beliefs model (

23), which has been used to guide research on a range of stigmatized conditions such as HIV-AIDS (

24) and mental health problems, introduced the concept and importance of perceived need for care in understanding the decision to seek care. This model posits that an individual’s beliefs about disease severity, need for care, and benefits of treatment predict health care behavior (

25).

Perceived need for care is a potentially powerful mechanism that may link treatment-seeking stigma and service use given that lack of perceived need is one of the reasons veterans cite most frequently for not seeking care. In a study of Canadian Armed Forces members, between 84% and 96% of respondents reported that they did not seek care because they did not perceive their mental health problems to be severe enough (

26). In a national sample of U.S. service members, lower perceived need for mental health care was associated with lower use of mental health services. Although perceived need may be affected by treatment-seeking stigma, it has received limited attention in the broader literature on veterans’ treatment-seeking stigma and even less in the literature related to female veterans’ treatment seeking.

Another factor that may be relevant to the relationship between treatment-seeking stigma and service use is mental health literacy. Mental health literacy refers to the extent to which individuals are knowledgeable about mental health problems and their treatment (

27). Stigma-reduction theory posits that mental health stigma can be reduced through increased knowledge of and contact with people experiencing mental health problems and seeking treatment (

28,

29). Consistent with this theory, research on civilian samples has found that individuals with higher mental health literacy have more positive perceptions about treatment and exhibit reduced social distance stigma (

30). Initial evidence also has supported the relationship between mental health literacy and perceived need for care in civilian samples because individuals with higher mental health literacy have been better able to identify mental health problems, and this ability has been hypothesized as the first step in the treatment-seeking process (

31–

34). However, research on how mental health literacy affects female veterans’ treatment seeking remains extremely limited.

Although treatment-seeking stigma, perceived need for care, and mental health literacy have all been shown to affect treatment seeking, to our knowledge, no study has examined relationships among these factors in a longitudinal sample of military veterans or female veterans specifically. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine associations among these variables in a study of female veterans that included multiple assessments.

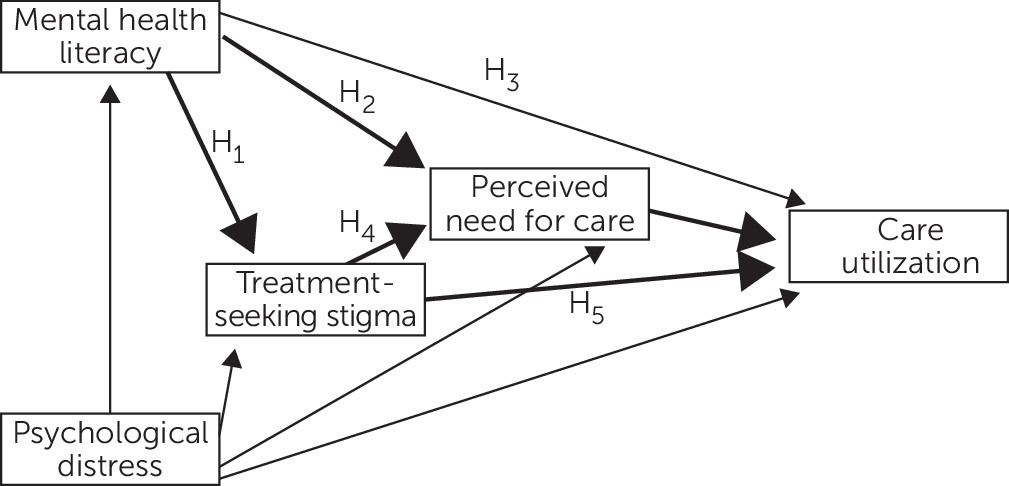

Figure 1 depicts a visualization of our hypothesized model. We hypothesized that when accounting for the role of psychological distress, women who demonstrated higher mental health literacy would report less treatment-seeking stigma (path H

1), higher perceived need for care (path H

2), and higher likelihood of mental health service use (path H

3).

In addition, we expected that women who reported more treatment-seeking stigma would report lower perceived need for care (path H4) and lower likelihood of mental health service use (path H5). Finally, we hypothesized that perceived need for care would mediate the effect of mental health literacy and treatment-seeking stigma on mental health service use, such that those who reported higher mental health literacy and lower treatment-seeking stigma would perceive greater need for care, which, in turn, would be associated with increased service use. Darker paths depict mediation by perceived need for care on care utilization. Nonhypothesized pathways are included to demonstrate how psychological distress was controlled for in the model.

Methods

Sample

Data were drawn from a larger, three-wave prospective national survey of female veterans conducted between November 5, 2014, and January 8, 2017. Participants were recruited through KnowledgePanel, a probability-based, nonvolunteer access survey panel of 55,000 U.S. adults that is representative of approximately 97% of U.S. households (

35). Among 548 female veterans in the sampling frame, 411 participated at time 1 (baseline). Of these participants, 171 completed the latter two timepoints (time 2, 18 months postbaseline; time 3, 24 months postbaseline).

For the purpose of this study, which required collection of measures of distress, mental health literacy, and treatment-seeking stigma at time 2 and service use at time 3, we relied on time 2 and time 3 data from these 171 participants. Demographic comparisons between responders and nonresponders at both timepoints were nonsignificant. Institutional review board approval was obtained. Participants completed Web-based surveys at time 1, time 2, and time 3. For more details about recruitment processes, see Iverson et al. (

36).

Measures

Psychological distress.

A summed composite of standardized scores on the anxiety subscale of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (

37); the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (

38); and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (

39) was created to represent general psychological distress. Each measure contributing to the composite score demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.94–0.95). The composite measure was also reliable (Cronbach’s α=0.91). These data were measured at time 2.

Treatment-seeking stigma.

To measure treatment-seeking stigma, we used the negative beliefs about treatment seeking subscale of the Endorsed and Anticipated Stigma Inventory (

40). The scale consists of eight items that assess the degree to which individuals endorse stigmatizing beliefs about mental health treatment seeking (e.g., “I would think less of myself if I were to seek mental health treatment”; “Seeing a mental health provider would make me feel weak”) on a Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. This scale demonstrated structural, convergent, and discriminant validity in veteran samples as well as good reliability (

40). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s α=0.90). These data were measured at time 2.

Mental health literacy.

We developed the seven-item Mental Health Literacy scale because there was no established measure of mental health literacy that met the needs of our study. This measure assesses the extent to which individuals have knowledge about the etiology of mental health problems (e.g., “I am knowledgeable about the types of military experiences that can cause mental health problems”), knowledge of symptom identification (e.g., “I am familiar with the symptoms of PTSD”), and knowledge of effective treatment options (“I would know how to get mental health treatment if I needed help”) on a Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. This scale demonstrated good internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s α=0.89). A sum score of the seven items was used for hypothesis testing. These data were measured at time 2.

Perceived need for mental health treatment.

To assess perceived need for mental health treatment in the past 6 months (time 3), we used a single dichotomous item: “Have you had an emotional problem that required health care?”

Health care utilization.

A dichotomous variable was created to assess any mental health service use—including urgent care, inpatient treatment, outpatient psychotherapy, and medication use—for PTSD, depression, anxiety, or other mental health problems, including alcohol or drug use, or attending a support group for a mental health problem in the past 6 months in VA or civilian health care settings. These data were measured at time 3.

Analytic Plan

Bivariate associations between predictor and outcome variables were examined by using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 20 (

41). Hypotheses were tested via path analysis in Mplus, version 7.11 (

42). Weighted least squares was used for model estimation to better account for dichotomous mediator and outcome variables (i.e., perceived need for mental health care and service use;

43). Bias-corrected bootstrapping was used to test mediation (

44). Confidence intervals (CIs) of the indirect effects that did not contain zero were used as evidence of significant mediation.

Results

Full demographic information is presented in

Table 1. Study data were screened before data analysis to test the assumptions related to path analysis (e.g., normality and multicollinearity), and no violations were found. Mean±SD scores for study variables and correlations between variables are presented in

Table 2.

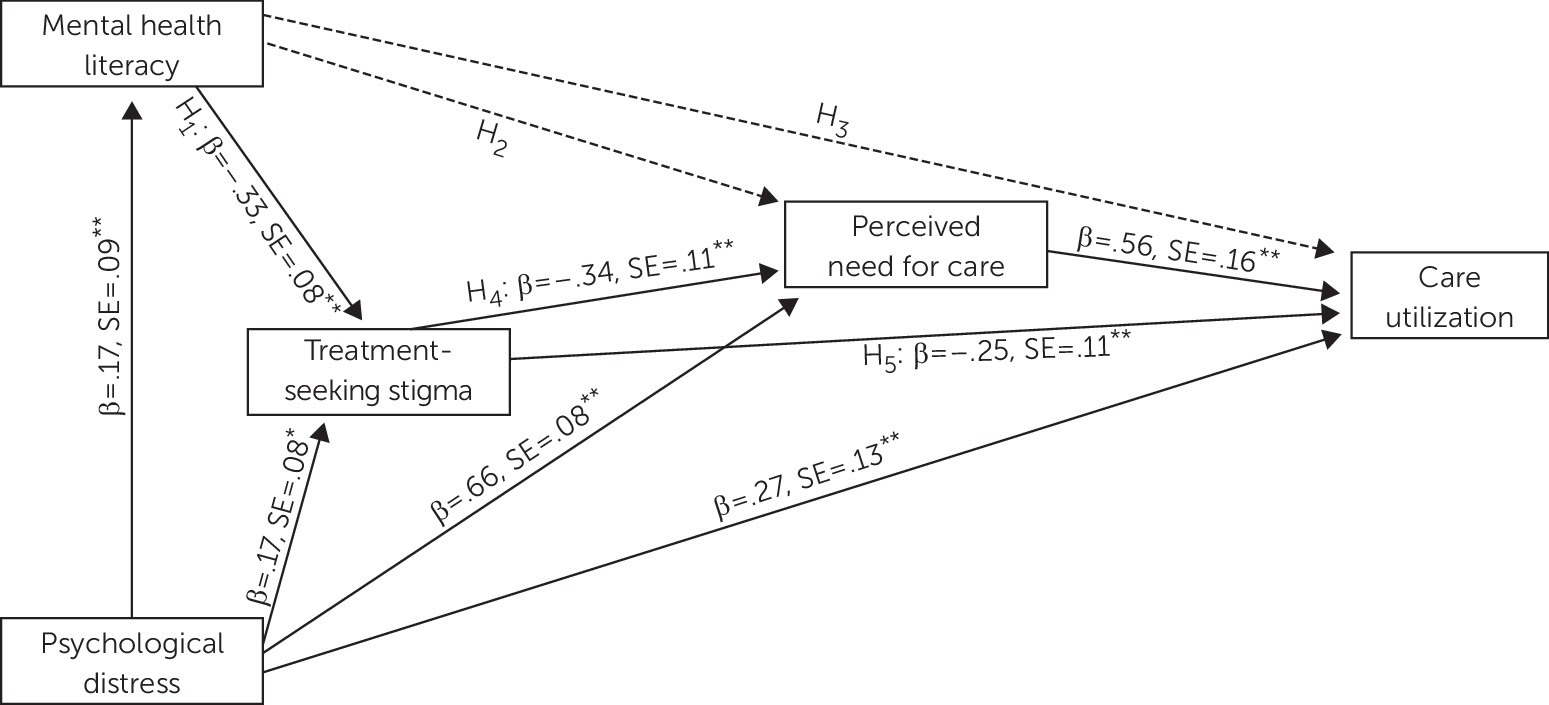

Results confirmed our hypothesis that after the analyses accounted for the role of psychological distress, women who reported higher mental health literacy endorsed less negative beliefs about treatment seeking (

Figure 2; pathway H

1; β=−0.33, SE=0.08, p<0.001). However, we did not find support for the proposed positive relationship between mental health literacy and perceived need for care (

Figure 2; pathway H

2) or between mental health literacy and mental health care utilization (

Figure 2; pathway H

3). However, results supported our hypotheses that women who endorsed more negative beliefs about treatment seeking also reported lower perceived need for care (

Figure 2; pathway H

4; β=−0.34, SE=0.11, p=0.003) and lower likelihood of health care utilization (

Figure 2; pathway H

5; β=−0.25, SE=0.11, p=0.02).

We found partial support for the hypothesis that after the analyses accounted for the role of psychological distress in the model, perceived need for care would mediate the effect of both mental health literacy and treatment-seeking stigma on mental health care use (

Figure 1). Perceived need for care mediated the relationship between treatment-seeking stigma and use (β=−0.19, SE=0.08, 95% CI=−0.39 to −0.09) to indicate that those who reported higher mental health literacy and lower treatment-seeking stigma perceived greater need for care and were therefore more likely to report service use.

However, perceived need for care did not mediate the association between mental health literacy and service use (β=0.11, SE=0.08, 95% CI=–0.05 to 0.09) because mental health literacy did not have a significant direct effect on perceived need for care and the CI for the indirect effect contained zero. Perceived need for care mediated the relationship between psychological distress and care utilization because the CI for the indirect effect did not contain zero (β=0.37, SE=0.12, 95% CI=0.18 to 0.57). Finally, mental health literacy had a significant indirect effect on service use through treatment-seeking stigma (β=0.08, SE=0.04, 95% CI=0.02 to 0.17).

Discussion

This study extends current knowledge on the role of mental health literacy, treatment-seeking stigma, and perceived need for care in female veterans’ service use within a longitudinal study. We demonstrated that mental health literacy reduces treatment-seeking stigma, and it indirectly increases female veterans’ likelihood of service use through its impact on treatment-seeking stigma. We also demonstrated that perceived need for care mediates the relationship between treatment-seeking stigma and service use among female veterans. Our findings extend stigma reduction theory by elucidating a mechanism in the relationship between treatment-seeking stigma reduction and increased health care use, suggesting that mental health literacy leads to reduced treatment-seeking stigma, which, in turn, is associated with increased perceived need for care, leading to increased likelihood of service use among female veterans.

Altogether, these results suggest that one way to reduce treatment-seeking stigma among female veterans is to target mental health literacy. Mental health literacy interventions such as Mental Health First Aid and beyondblue are designed to increase mental health knowledge, decrease stigma related to mental health problems and treatments, and increase willingness to refer to treatment (

45–

47). Findings reinforce the importance of these efforts and extend current knowledge by documenting that the impact of mental health literacy on service use is indirect, through reduced treatment-seeking stigma.

These findings also highlight perceived need for care as a key mechanism explaining the relationship between treatment-seeking stigma and service use among female veterans. Although treatment-seeking stigma has been identified as a key barrier to mental health care among both female and male veterans, few studies have examined exactly how any type of stigma affects treatment seeking. Our findings suggest that the extent to which female veterans endorse treatment-seeking stigma affects the extent to which they feel that they need mental health care, which, in turn, affects whether they seek mental health care. Future research examining other stigma mechanisms (e.g., anticipated stigma, internalized stigma) and cultural values (e.g., self-reliance) and their relationship with perceived need and service use is also important given recent research highlighting the potential contribution of cultural values to veterans’ endorsement of treatment-seeking stigma (

20).

This study has several limitations. We did not include additional variables that may be particularly relevant for female veterans, such as their perceived level of comfort within the Veterans Affairs care setting (

48,

49), or assess other cultural values that may influence health care behavior, such as exaggerated self-reliance. We also did not examine the role of logistical barriers to care in the associations between variables in this study. In addition, the health care use measure addressed whether veterans used any mental health care rather than the frequency, nature, or outcomes of their service use. Therefore, this study cannot determine whether mental health literacy, treatment-seeking stigma, or perceived need for care are predictive of retention in treatment or clinical outcomes. Furthermore, it is possible that individuals may underreport their frequency of health care use, a limitation of relying on self-reports.

In addition, this study examined the impact of mental health literacy on treatment-seeking stigma, but it is important to note that mental health stigma is complex and multidimensional, composed of different stigma mechanisms that may differentially affect outcomes for people experiencing mental health problems (

15). It may be the case that other stigma mechanisms, such as anticipated and experienced stigma, also play a role in the relationship among mental health literacy, perceived need, and treatment seeking. Future research on how different stigma mechanisms operate together (or in process) is needed to optimize antistigma interventions to reduce stigma and increase treatment-seeking rates among civilians and veterans experiencing mental health problems. Finally, in our models, we statistically controlled for psychological distress, which is an important predictor of service use (

50). However, it is also important to consider other predictors, such as functional impairment (

51,

52).

There are several other valuable directions for future research. Specifically, it will be important to examine whether results generalize to female civilians as well as male veterans and civilian samples. Prior research suggests that treatment-seeking stigma may affect female and male veterans’ treatment seeking similarly (

19); however, no research to our knowledge has examined the possibility of gender differences in the impact of mental health literacy on veterans’ experiences of stigma and treatment seeking. Future research should also examine whether findings vary on the basis of the nature and severity of diagnosis (

15,

19) and as a function of race-ethnicity and related cultural values (

53).

Another important next step will be to examine whether there are differences in the effectiveness of mental health literacy interventions at increasing perceived need for personal mental health care versus care for another person. Future studies should also assess treatment expectancy to distinguish the unique impact of mental health literacy (

54). Given recent empirical research suggesting that framing mental health problems as treatable reduces social distance stigma and increases positive expectations about treatment (

55), further research should test empirical methods to frame mental health concerns to reduce treatment-seeking stigma.

Conclusions

This study takes an important step in better understanding the relationship between treatment-seeking stigma and health care use among female veterans. Findings suggest that it is important to examine and develop targeted interventions that address the multiple and unique pathways toward treatment seeking among female veterans.