Over 10% of youths in the United States are diagnosed as having attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (

1). It has two well-established treatments: medications (predominantly central nervous system [CNS] stimulants) and behavioral therapies. Medication is the most common treatment across ages and produces the largest and quickest reduction in symptoms (

2–

5). Behavioral therapy is the recommended initial treatment for young children (

5) and significantly reduces symptoms and improves functioning in school-age youths (

2,

6,

7). Medication is the recommended initial treatment for adolescents because of the larger evidence base, but there is emerging evidence that behavioral therapy is efficacious (

5,

8). Adding behavioral therapy to medication optimizes functioning, reduces the dose of medication needed (

2,

9–

11), and may improve how desirable parents rate treatment (

12). Despite these benefits, rates of behavioral therapy use are low. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly three-quarters of children with ADHD use medication, but less than half received any behavioral therapy in the past year, leading to calls for identifying barriers to behavioral therapy (

3,

13).

One of the primary theorized reasons for poor behavioral therapy uptake is limited availability; patients must access specialty centers to receive it, whereas medication is widely available in primary care (

13–

15). However, rates vary widely in areas with similar provider densities (

16). There has been a nationwide trend toward integrating pediatric behavioral health services into primary care (

17) and developing statewide care coordination to link families with resources (

18,

19), which should increase behavioral therapy uptake. However, recent studies show little change, with under a third of patients with ADHD currently receiving any behavioral therapy (

3), while rates of ADHD diagnosis and medication treatment have increased (

1,

20,

21). Therefore, it appears that simply increasing access may not resolve the problem. Patient and provider factors have been identified as possible barriers but have not been systematically explored (

4,

22).

Methods

Procedures and Measures

We completed a retrospective review of insurance claims from 2008–2014 by using the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database (IBM Truven Health Analytics). The study was not classified as human subjects research and was exempted by the governing institutional review board. MarketScan consists of reimbursed health care claims from a selection of large employers and commercial health plans. It has claims information from more than 50 million employees and family members per year, ages 0–64. Claims are identified by a unique enrollee identifier containing information on inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug use, plus patient age, gender, geographic location, and type of insurance. The family identifier, a unique one- to nine-digit number, groups families in the data. Medical diagnoses were coded by ICD-9 and medical procedures by Current Procedural Terminology, 4th edition, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System.

Medication use was defined as filling at least one prescription during the assessment period. We included all Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved ADHD medications plus clonidine and guanfacine because they are commonly prescribed for ADHD (

29). Other off-label medications commonly used for indications besides ADHD, such as bupropion, were not included. Receipt of behavioral therapy was measured by review of billing codes for any individual, family, or group counseling and defined as at least one code for a billable service during the 7-year span. Codes included 90804–90809, 90816–90819, 90821, 90822, 90846, 90847, 90849, 90853, G0410, G0411, H0035–H0037, H2012, H2013, H2017–H2020, S9480, and T1027.

Study Population

Included cases were patients ages 0–17 during any of the seven annual cohorts (2008–2014) with at least two documented visits with an ADHD billing code and at least 1 year of enrollment in the database. One year of enrollment was required to ensure that families had reasonable time to access treatment after receipt of an ADHD diagnosis. ICD-9 codes for ADHD included 314.00, 314.01, and 314.9.

Covariates

The pool of ADHD patients was stratified by age (<6, 6–12, and ≥13), gender, geographic region (West, South, Northeast, North-Central, and unknown), type of medical provider seen (primary care only versus psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse practitioner [psychiatric provider]), treatment year, presence of any comorbid psychiatric disorder (all ICD-9 behavioral health codes), presence of a disruptive behavior disorder (codes 312.8, conduct disorder; 313.81, oppositional defiant disorder; and 312.9, disruptive behavior disorder not otherwise specified), and severity of behavioral health disorder. Severe presentations were defined as receipt of behavioral health care in an emergency room or inpatient setting for any behavioral health condition. We also examined the impact of use of behavioral therapy and ADHD medication use by older siblings with ADHD and psychiatric disorders of parents, defined as having at least one diagnostic code for any psychiatric disorder.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were used for exploring cohort demographic factors and distributions of variables. Univariate associations between each factor of interest and the outcome variable were examined by using chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. Multivariable analysis was performed by using logistic regression. A model was computed to examine rates of behavioral therapy use among medication users versus nonmedication users while adjusting for effects of covariates. To examine the association of medication use on future behavioral therapy use, we reran the analyses excluding patients who had received any billable behavioral therapy service before medication. A lookback period was not employed in the primary analyses, but sensitivity analyses were run that limited the cohort to those with no ADHD codes or ADHD medications for 6 months prior to the assessment period. All analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.4. All statistical tests were two-sided, with p values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Multiple variables were associated with increased behavioral therapy uptake, including age, geographic region, gender, prescriber type, severity of presentation, and psychiatric comorbidity. Children prescribed medication were 2.5 times less likely to use behavioral therapy than those not prescribed medication. Medication was associated with a fourfold reduction in future behavioral therapy uptake, even among preschoolers. This association held after the analysis adjusted for multiple covariates affecting behavioral therapy uptake. Results parallel what was observed in an RCT, in which despite robust medication effects, use of behavioral therapy before medication produced better outcomes at lower costs than the reverse sequence, partly because of poor uptake of behavioral therapy by participants who were initially prescribed medication (

23,

24). Because over 6% of U.S. school-age youths are treated with CNS stimulants (

1) and because medications are the most common initial ADHD treatment (

30), the potential impact of these findings is appreciable. To the extent that combined treatments enhance long-term functioning over unimodal treatments (

31,

32), the negative association of use of one treatment with use of the other could partly explain why medication alone produces limited long-term benefits even when adherence is strong (

33,

34).

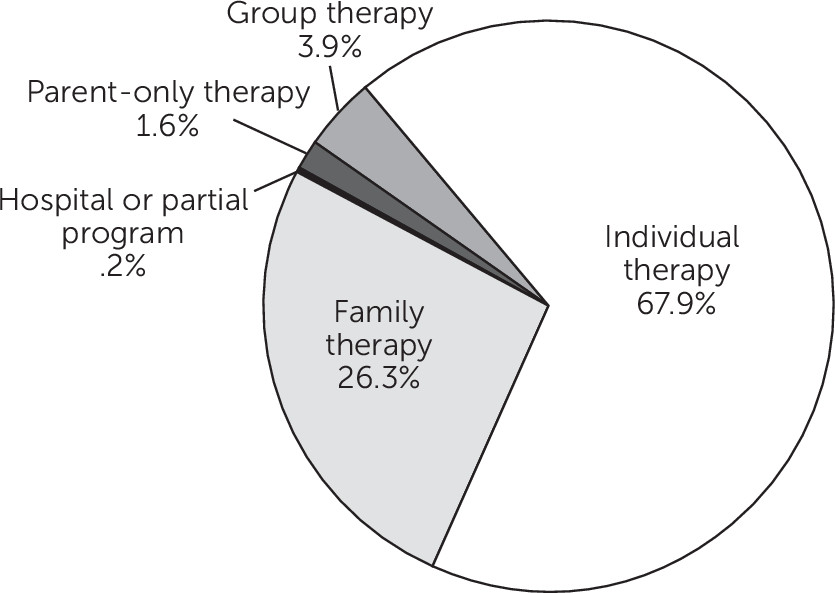

The rate of use of any behavioral therapy approached 50%, comparable to rates in past studies (

3,

13,

35). However, it appears that the rate of receipt of potentially efficacious behavioral therapy was far lower than 50%. The number of therapy sessions attended affects outcomes (

36,

37). In any 4-month span, barely 50% of youths attended at least four sessions, which is half the duration of the shortest evidence-based programs (

38). Under 2% of therapy codes were for parent-only sessions, one of the most well-supported formats for ADHD treatment (

6). Individual therapy accounted for most sessions, and many forms of this modality are not evidence based for ADHD (

5,

10). Hence, both the dose and format of received therapy services may often be suboptimal.

Systems, parent, and provider factors have been identified as barriers (

4,

22,

27,

39). Offering services in easily accessible settings and using engagement interventions to increase motivation for care increase uptake of therapy (

40–

43). In a prior RCT, engagement techniques were employed while free and accessible therapy was offered in the same setting as medication. Yet, use of medication was still significantly associated with lower behavioral therapy uptake (

23). Therefore, a multimethod approach targeting patients, parents, and providers may be needed to meaningfully increase rates of use of behavioral therapy.

What drives this negative association of medication use with behavioral therapy uptake could not be ascertained in this analysis. One possibility is that medication alleviates any need for additional treatment. We adjusted for severity, and this relationship persisted, although our severity threshold was coarsely limited to use of emergency or inpatient services. Medication effects on use of behavioral therapy were also robust in a federally funded study in which only children manifesting objectively verified impairment after 8 weeks of systematic medication treatment were randomly assigned to receive additional treatment (

23). Availability of therapy providers is limited, and they are often not located in the same setting as medication prescribers. However, low uptake occurs even when access is readily available, such as in integrated primary care practices (

16,

41,

44). Combined treatments may be too burdensome for families, but previous studies have not found that use of behavioral therapy inhibits use of medication (

23,

44,

45).

We theorize that the immediate and visible reduction in ADHD symptoms produced by medication (

2,

46) reduces parental and possibly provider motivation to seek more intensive treatments because time commitments are a barrier to use of behavioral therapy (

47). Symptom changes are easily observed, but acute symptomatic improvement and sustained functional improvements are poorly correlated because impairment often persists when symptoms remit (

48–

50). This disconnect makes it challenging to predict long-term outcomes based on initial response. Therefore, increased dissemination efforts focusing on ADHD as a chronic condition (

5), emphasizing functional remission over acute symptomatic improvement, and using impairment versus symptoms as the metric for titrating treatment may improve behavioral therapy uptake.

Children under 6 (versus those 6–12), those with more severe clinical courses, and those with comorbid psychiatric disorders were more likely to receive behavioral therapy. These findings are consistent with prior work (

3,

13,

22,

44) and treatment guidelines in which behavioral therapy is the recommended first-line treatment for young children (

5,

46,

51,

52). For school-age youths, medication is recommended as a core component of ADHD treatment (

5,

46). Combining behavioral therapy with medication can optimize long-term functioning at lower medication dosages; therefore, it would be reasonable to consider behavioral therapy as an adjunctive treatment for medicated youths of all ages (

9,

11). However, the sequence of medication followed by behavioral therapy is less efficacious and cost-effective than the sequence that starts with behavioral therapy (

23,

24). Yet medication first is the most common pattern according to these results and other naturalistic studies (

30,

45). Therefore, it does not seem advisable to refer patients for behavioral therapy only when impairment persists after medication treatment. Delaying behavioral therapy until after medication use may be one reason why it has been challenging to find evidence of improved long-term outcomes for youths with ADHD despite large increases in health care spending for this disorder over the past 2 decades (

34,

53).

The primary limitation of this study was the exclusion of children with public health insurance. Past work has found higher rates of use of behavioral therapy among youths covered by Medicaid (

3,

13,

22,

35,

45,

54). It is possible that the impact of medication use on behavioral therapy use may be lower in this population. Therefore, replication of results in a nationwide pool of publicly insured youths is advised. However, even when publicly insured youths are included, rates of use of behavioral therapy remain well below rates of medication use regardless of patient age (

4,

13,

25,

30). Because of limitations of the data set, we could not measure the impact of race or ethnicity, verify family relationships, or determine whether patients exiting and returning to insurance coverage were counted as the same or distinct cases. Our analyses would miss unbilled services, such as those provided through schools. However, past studies that included school-based supports found similar predictors of use of behavioral therapy (

3,

13,

22). We were not able to verify the diagnosis of ADHD but we required that an ADHD diagnostic code be present for at least two separate visits. Unlike other behavioral health conditions, ADHD is not thought to be underreported (

55). Rates of comorbid behavior disorders were low for an ADHD sample (

56) but consistent with those in past studies of claims data (

57), which was likely attributable to providers preferentially billing for ADHD because it is the only disruptive behavior disorder with FDA-approved medications.