Disparities among racial-ethnic groups are apparent across multiple diagnoses and treatments (

1–

5). In particular, patients from racial-ethnic minority groups adhere to both psychotherapy and medication for depression less than non-Hispanic white patients do (

4). Although inequalities could result from interactions with different levels of the health system (

6), disparities that may result from providers have received substantial attention (

5,

7).

Many initiatives for addressing disparities (

8) operate on the belief that disparities are, in part, a provider-specific problem (

7,

9–

14). However, no clear evidence has been found that disparities can be localized to specific providers. Determining whether some providers have larger disparities in their caseloads than others is an important step in understanding how levels of the health system affect the health of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups and in developing targeted quality improvement efforts that will reduce disparities.

Methods

Mental Health Research Network

Data were obtained from a subsample of electronic medical records from health systems in Southern California and Washington State in the Mental Health Research Network’s (MHRN’s) Virtual Data Warehouse (VDW) (

4,

16,

28) and are subject to an ongoing approved institutional review board to the MHRN. The sample was limited to patients with depression who were age 18 or older and who began treatment with psychotherapy between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2013 (N=275,095), and/or began treatment with antidepressants between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013 (N=331,776). Data regarding how patients were assigned to providers were not available.

To ensure adequate representation of non-Hispanic white patients and patients from racial-ethnic minority groups within caseloads, we restricted the sample to providers who saw at least 10 patients, at least one of whom self-identified with a racial-ethnic minority group. A total of 4,821 providers offered antidepressant treatment, and 4,794 offered psychotherapy. Antidepressant treatment was offered by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physicians, and “others,” whereas psychotherapy was offered by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physicians, psychiatric associates, psychologists, social workers, and “others.” The mean±SD number of patient visits within providers’ caseloads was 255.7±312.3, ranging from 10 to 1,811.

Measures

Race-ethnicity.

Self-reported race-ethnicity was obtained from the VDW. Patients were asked to complete a self-report form that included separate questions about race-ethnicity. The recoding of race-ethnicity followed national recommendations for mutually exclusive race-ethnicity categories (

29). Our final analyses used a binary race-ethnicity variable, which was coded as racial-ethnic minority (52.8%) or non-Hispanic white (47.1%). We used this binary variable because our prior work with MHRN data showed lower adherence rates among patients from all racial-ethnic minority groups compared with non-Hispanic white patients (

4).

Early antidepressant adherence.

We defined early adherence to antidepressant medication as any antidepressant refill of at least 90 days’ supply within 180 days of first filling a prescription. We identified medical records and insurance claims with filled antidepressant prescriptions after the index date visit. Eligible antidepressant treatment included all drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of major depression, excluding trazodone (often prescribed for insomnia). This definition of adherence is consistent with prior work and Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set benchmarks (

30–

32).

Early psychotherapy adherence.

We defined adherence to psychotherapy as attending at least one psychotherapy session within 90 days after the diagnostic interview (

16). We defined an episode of psychotherapy with the Current Procedural Terminology codes (diagnostic interview and assessment, individual psychotherapy, insight-oriented, etc.). We excluded codes that captured visits of less than 30 minutes or that were designated for medication management only.

Covariates.

To control for differences in case mix across providers, we used measures of a patient’s prior mental health visits, prior prescription for antidepressants in the 5 years prior to the new episode, and neighborhood income. We used census data to measure the patient’s neighborhood income. We defined lower income as a neighborhood median income lower than $40,000.

Statistical Analyses

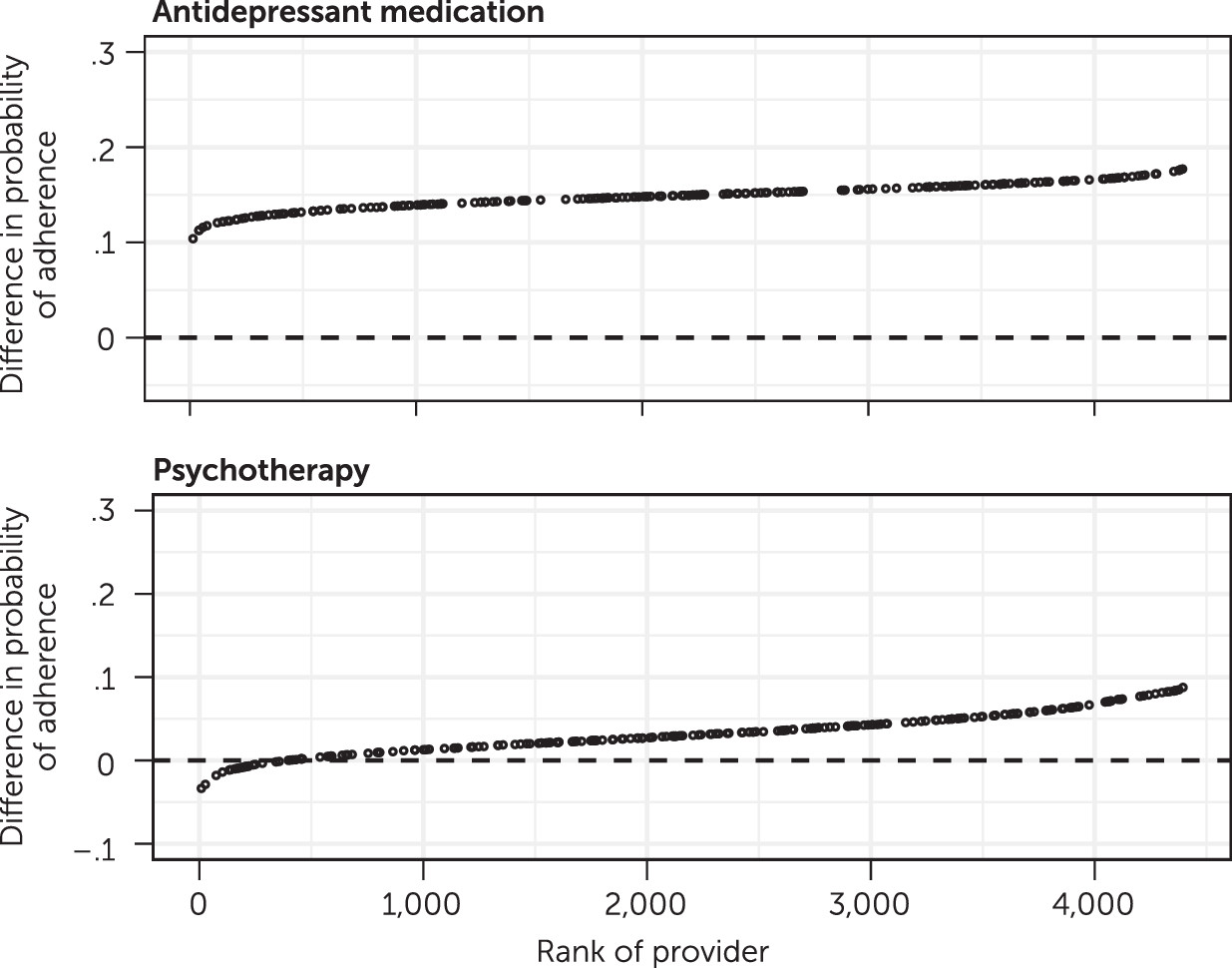

We used Bayesian logistic mixed-effects models to estimate provider-specific disparities in adherence (

33). Each model included identification with a racial-ethnic minority group, neighborhood income, grand-mean–centered prior mental health visits, and grand-mean centered prior antidepressant prescription as fixed effects. Random effects were at the provider level and included a random intercept and a random slope for racial-ethnic minority status. The random slope for racial-ethnic minority status estimated a provider-specific difference in adherence among patients from racial-ethnic minority groups and non-Hispanic white patients. Negative-value provider-specific differences indicated that a specific provider’s patients from racial-ethnic minority groups had a lower probability of adhering to treatment than did non-Hispanic white patients. The variance component of the random slope provided the test of our main hypothesis, ascertaining how much disparities in adherence between patients from racial-ethnic minority groups and non-Hispanic white patients varied across providers. Model 1 included a correlation between the random effect for the intercept and the random slope of the racial-ethnic status effect, which tested whether the adherence rate among a provider’s non-Hispanic white patients was related to disparity in adherence between the two racial-ethnic groups (i.e., the difference in adherence between patients from racial-ethnic minority groups and non-Hispanic white patients in a provider’s caseload).

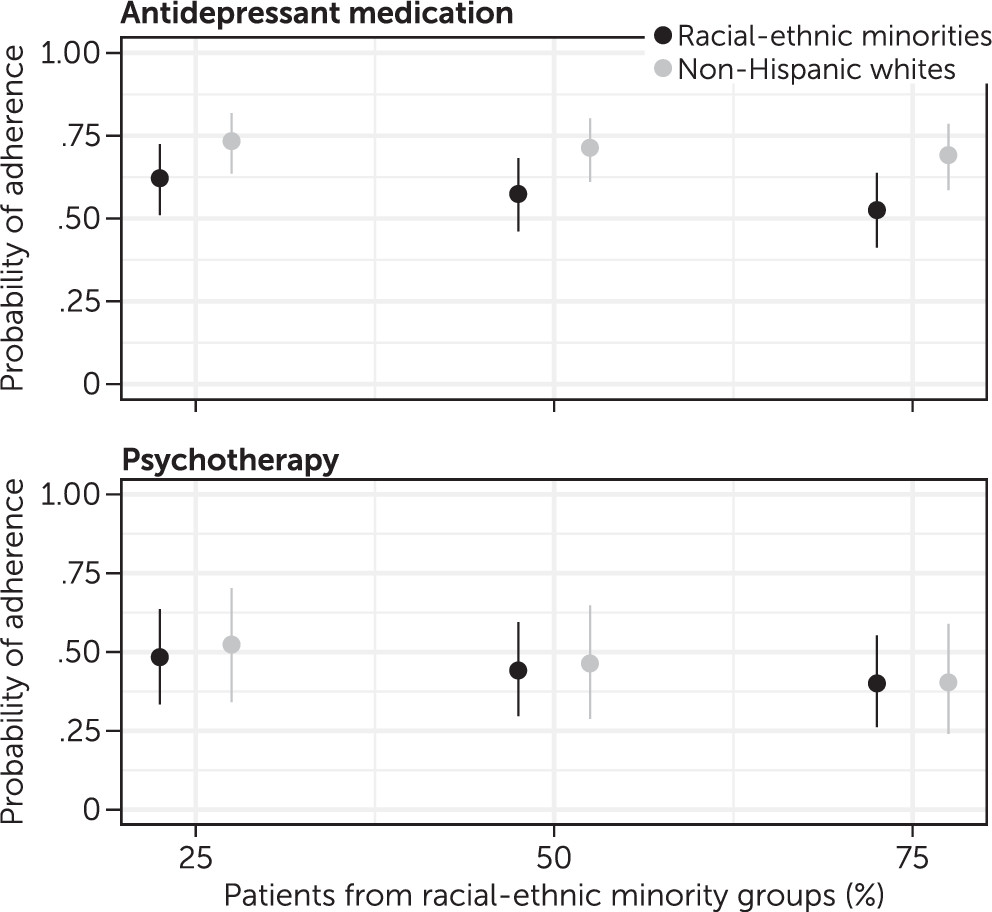

Model 2 was identical to model 1 except that it also examined whether the proportion of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups in providers’ caseloads was associated with patients’ adherence to treatment overall. Model 2 also included an interaction between the proportion of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups within a provider’s caseload and patient racial-ethnic minority status. This interaction tested whether the racial-ethnic diversity of a provider’s caseload moderated the size of the difference in adherence to treatment between non-Hispanic white patients and patients from racial-ethnic minority groups in a caseload.

Weakly informative prior distributions included: a normal distribution with a mean of 0±2 for fixed effects, a half-Cauchy with a location of 0 and scale of 1 for the standard deviation of the random effects, and LKJ prior with a shape parameter of 2 for the correlation between random effects (

33,

34).

Discussion

Consistent with prior work (

18,

20–

23), this study found that the extent of disparities in treatment outcomes partially depended on the provider. In psychotherapy, some providers overcame adherence disparities entirely; their non-Hispanic white patients and their patients from racial-ethnic minority groups adhered to treatment at equal rates. For some providers of antidepressant medication, the disparity was half of the overall main effect. Psychotherapy providers (but not antidepressant providers) whose non-Hispanic white patients adhered to treatment at higher rates had relatively larger disparities among all patients in their caseload. This finding points to the possible distinction between a provider’s ability to encourage patients from majority groups to adhere to treatment and his or her ability to work with patients from racial-ethnic minority groups in psychotherapy (

35).

One important caveat is that providers (of both medication and psychotherapy) who achieved high adherence rates with non-Hispanic white patients also had higher average adherence rates among patients from racial-ethnic minority groups. That is, even though they had higher disparities, providers with the highest adherence rates among white patients obtained better rates of treatment adherence among patients from racial-ethnic minority groups. These findings suggest that both patients from racial-ethnic minority groups and non-Hispanic white patients are more likely to adhere to treatment in consultation with some providers, but patients from minority groups do not match the gains that non-Hispanic white patients experience. This experience might mirror the ways some members of racial-ethnic minority groups experience other social domains (e.g., restaurants, education systems) (

36–

41). These individuals might have specific negative experiences in these settings that are unique to their racial-ethnic identification (e.g., low expectations, not feeling welcomed, microaggressions).

The source of provider-specific disparities cannot be determined from these data. It is possible that patients experience biased messages from their providers (

42) or have other negative experiences associated with the provider during their visit (e.g., check-in staff). Disparities might result from processes beyond the control of the health system (i.e., discriminatory experiences during transit in a predominantly white area). Because no providers of antidepressants had higher adherence rates among patients from racial-ethnic minority groups than among non-Hispanic white patients, provider variability seems constrained by factors that are not unique to specific providers. The behavioral process of attending psychotherapy sessions is more complex than is adhering to antidepressant medication (e.g., travel to multiple offices visits) and could be subject to additional factors that are beyond a provider’s control, such as a patient’s flexibility in work schedule and child care options. Alternatively, it is possible that disparities were smaller for providers with patients who generally adhered to treatment at lower rates than did patients of other providers because of a floor effect, such that some providers simply provide poor care indiscriminately. Racial-ethnic disparities may still exist among these providers but might be masked by more general problems with engaging patients. Future research should target providers and settings with overall good performance but where disparities remain.

We also found that patients with a provider who treated a higher proportion of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups had lower adherence regardless of the patient’s own race-ethnicity. Providers and patients in practices with more patients from racial-ethnic minority groups may face challenges different from those of providers delivering care in practices where a majority of patients are non-Hispanic white.

Accordingly, the proportion of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups in a provider’s caseload may be a proxy for other clinic or neighborhood characteristics affecting adherence (

25,

43–

45). Caseloads that have more patients from minority groups could be a marker for practicing in a more segregated and/or disadvantaged area, which might affect white patients in the same geographic region. It is possible that these provider-specific disparities also interact with patient and clinical factors, in that patients from racial-ethnic minority groups who visit providers in practices with mostly non-Hispanic white patients may engage with medical care on the basis of other individual factors (e.g., increased English fluency, socioeconomic status, generational status).

The proportion of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups had opposite effects on disparities for psychotherapy and for antidepressants. For psychotherapy, disparity decreased as the proportion of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups increased. Alternatively, for antidepressants, the disparity was larger for providers with caseloads that were more diverse. The difference in the proportion effect between treatment modalities could be associated with increased use of different therapeutic skills when delivering psychotherapy as opposed to medication management or with a general difference in how academic training on delivering psychotherapy and on delivering medication incorporates multicultural perspectives.

There were several limitations of this study. First, patients were not randomly assigned to providers. Thus, it is possible that some differences among providers were the result of differences among patients. We raised this possibility above when noting that non-Hispanic white patients seen by providers with more patients from racial-ethnic minority groups may be different from white patients seen by providers with mostly white patients. Our findings are consistent with those from smaller samples in clinical trials, where bias in assignment is likely to be even smaller (

18). Second, we were not able to model clinic location along with provider. Thus, some of the provider differences in this study may have been due to the clinics in which those providers practiced.

Third, it is possible that provider variability in the systems we studied was relatively low compared with other systems because of the implementation of best-practice guidelines (

46). One of the guidelines to maximize medication adherence involved an automated refill ordering process via online patient portals or a telephone system. To that end, we might observe greater provider variability in medication adherence in less structured settings. Fourth, it is possible that prior treatment and income adjustments did not fully account for differences in patient case mix across providers. Fifth, it is possible that different racial-ethnic minority groups experience varying degrees of provider-specific disparities (see the

online supplement for similar results comparing non-Hispanic white and Hispanic groups).