Making effective health care more widely available in routine practice is a challenge across all areas of health care (

1), including mental health (

2). Fidelity assessments are an important strategy for monitoring implementation of an intervention in relation to the guidelines or standards that define it (

3). Fidelity feedback can guide new practice implementation and ongoing improvement. Applied across a system of care, it can play an important role in reducing practice variation and supporting more consistent delivery of high-quality care. However, measuring fidelity can be challenging, especially for psychosocial treatments in which performance criteria may not be defined and relevant data may not be available (

4).

Early psychosis intervention (EPI) is a comprehensive, team-based model of care that combines pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions to support client recovery from a first episode of psychosis. International research over the past 2 decades has demonstrated the benefits of EPI (

5), including the recent RAISE-ETP trial (Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode–Early Treatment Program) that compared coordinated specialty care and usual care for first-episode psychosis in 34 clinics across the United States (

6). Despite broad evidence of effectiveness, implementation has been variable owing to a variety of factors, including lack of program standards and lack of routine strategies and data for monitoring implementation (

7,

8).

The First Episode Psychosis Services Fidelity Scale (FEPS-FS) assesses fidelity to the essential components of first-episode psychosis services (

9). Development of the scale was based on systematic reviews, a rating of evidence, and an expert consensus process; therefore, the scale is based not on a specific model but rather on internationally defined elements of EPI (

10). The scale offers an opportunity to systematically assess implementation of EPI services.

In Ontario, Canada, capacity in EPI has expanded from five programs in 2004 to 45 programs currently, which are located throughout the province. Many programs participate in a government-funded Early Psychosis Intervention Ontario Network (EPION) and work collaboratively to improve the quality of care. In 2011, the Ontario government released EPI program standards to guide more consistent delivery of high-quality care in the province (

11). After consultation with its members, EPION undertook a study to implement fidelity reviews by using the FEPS-FS and to assess feasibility and value for sector improvement work. The objectives of the study reported here were to assess the degree to which early intervention programs in Ontario meet international evidence-based standards and to assess the utility of FEPS-FS for informing quality improvement in relation to program standards. A second study of the acceptability and feasibility of the fidelity review model is under way.

Methods

This cross-sectional cohort study conducted fidelity assessments in a volunteer sample of Ontario EPI programs by using the validated FEPS-FS. Assessments occurred during February to June 2017. The study protocol was approved by the research ethics boards of two of the authors’ (JD and CC) home institutions.

The FEPS-FS assesses 31 components of care, including individual treatments received by program clients and team practices to deliver care. Each component is rated on a 5-point scale, from 1, not implemented, to 5, fully implemented. Rating criteria are item specific and measure both content and coverage (e.g., number of clients receiving the component of care). An initial evaluation provided support for the interrater reliability and face and content validity of the scale. On the basis of the evaluation results, a rating of 4 was proposed as indicating satisfactory performance (

9). One scale item (percentage of incident cases of persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorder served in the catchment area) was not rated. Because persons with mood and bipolar disorders are also eligible for service in Ontario EPI programs (

11), it was decided that this item as currently defined was not relevant to Ontario practice. Thus only 30 items were rated.

Assessments were conducted by using a volunteer, peer assessor model that included EPI program staff and evaluation specialists. After attending a 2-day training session, teams of three assessors (two EPI staff and one evaluator) were formed to conduct the fidelity reviews. Each included a 2-day site visit during which the team interviewed staff, clients, and families; reviewed client charts; observed a team meeting; and examined program documents (e.g., policies, educational handouts, and manuals) and administrative data (e.g., caseload, annual admissions, and length of stay). After the visit, the assessors developed preliminary fidelity ratings for the 30 FEPS-FS items, which were finalized at a subsequent consensus meeting with a fidelity expert. These ratings were reported back to programs, along with a narrative on program strengths, weaknesses, and improvement suggestions.

In addition to the training, assessors received a detailed manual of item definitions; instructions on how to summarize data from the various sources to make the ratings; and data collection tools, including interview guides, a chart abstraction template, and a report template. These supports, along with the consensus meetings, were intended to enhance consistency of ratings across the diverse assessor teams.

Program recruitment occurred through an e-mail invitation to members of the provincial EPION. Among the programs that volunteered to have a review, purposive sampling was used to capture variation in program size (clinical staffing) and location.

Mean fidelity ratings were computed per program (mean rating across the 30 items) and per item (mean rating across the nine programs). Per program, the percentage of ratings with values of 4 or 5 was calculated. Descriptive statistics were compiled to report the mean fidelity ratings and range at program and item level.

Results

The sample included nine EPI programs [see the online supplement]. These were located throughout the province. Five were housed in hospitals and four in community organizations. Program size, based on total clinical staff per program, ranged from small (fewer than three full-time-equivalent [FTE] clinical staff) to large (more than eight FTEs). Although total program caseloads varied, individual caseloads did not exceed 20 clients per clinical FTE.

Across the 30 items, the mean fidelity scores per program ranged from 3.1 to 4.4 [see online supplement]. Five of the nine programs had a mean fidelity score exceeding 4 (satisfactory performance). Across the programs, the percentage of the 30 items rated as 4 or 5 (satisfactory or exemplary) ranged from 47% to 80%.

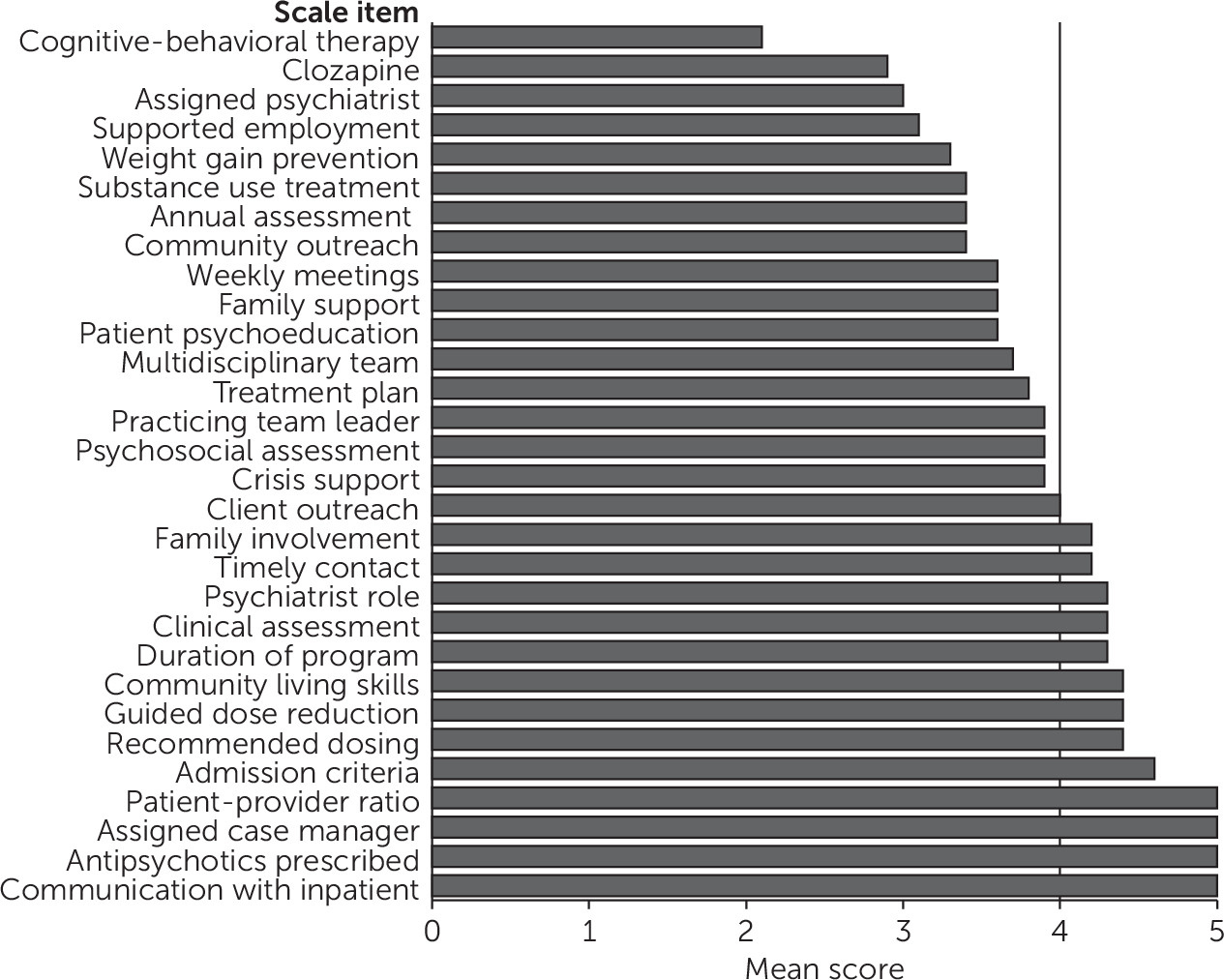

Figure 1 reports the mean fidelity rating per item across the nine programs. Ratings ranged from 2.1 to 5.0, and for most items, ratings spanned the full range of values (1 to 5). Items assessing structural components of the model (e.g., patient-provider ratio and assigned a case manager) and prescribing practices (e.g., antipsychotics prescribed) were among the highest rated, and items assessing psychosocial treatments (i.e., provision of cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], supported employment, weight gain prevention, and substance use treatment) were among the lowest. Ratings for clozapine treatment and assigned a psychiatrist were also low.

The program mean fidelity scores were lower for smaller programs. At the item level, smaller programs received lower ratings for some team practice items (e.g., weekly meetings and multidisciplinary team) and psychosocial care items (family support, CBT, weight gain prevention).

Discussion

Fidelity is a key ingredient for the systematic implementation of evidence-based interventions in community settings (

3). In Ontario, EPI is an established model of care, but systematic monitoring of quality is lacking. This study provided an opportunity to use the FEPS-FS to assess adherence to EPI standards in Ontario EPI programs. In addition, this is the first study we are aware of to describe the use of peer raters to assess fidelity to first-episode psychosis services.

The results showed satisfactory or exemplary performance for many EPI model components, but they also highlighted areas with lower adherence. In general, performance was higher for structural model components and lower for psychosocial interventions. Other research has also found higher adherence to structural components, compared with process components of care, which can be more complex to deliver and often involve multiple staff (

12).

Two common problems affected delivery of the psychosocial components. One was lack of consistency and standardization in delivery, which was partly attributed to a lack of manuals and protocols. The other was inconsistent documentation about client contacts, which limited assessor ability to judge the quality and frequency of program delivery. In the recent RAISE initiative in the United States to implement and evaluate delivery of coordinated specialty care for first-episode psychosis, great care was taken by project teams to develop implementation resources (manuals and documentation templates) (

6,

13), and wider implementation of the model using these resources is under way (

14). In Ontario, the EPION network is exploring implementation of protocols and tools for metabolic monitoring and care transitions.

Although only nine programs were as-sessed in this study, the FEPS-FS was able to capture variation in implementation, both within and across programs. While the results aligned with previous sector key informant surveys on standards adherence (

15), having a structured review process that was conducted by trained external assessors enhanced the credibility of findings. The results have stimulated reflection among program personnel about current practice, and a number have expressed plans to use the data to guide quality improvement.

A benefit of using the fidelity assessment across programs was that common implementation challenges were identified in which a sector response could be considered. For example, adherence to CBT delivery was low for nearly all programs. This reflects in part the difficulty (cost and accessibility) of obtaining CBT certification in the Ontario system and has raised the question of whether and how to make certification more accessible. A similar issue pertains to supported employment delivery, in which low adherence was attributable, in part, to lack of access to supported employment specialists in Ontario.

Fidelity results tended to be lower for the smaller programs, but there was variability. In a prior provincial survey of EPI programs (

15), smaller programs similarly reported more delivery challenges, but they also described strategies to enhance capacity. These included belonging to a local or regional EPI program network that shared policies, training, and specialty staff and forming service partnerships with local providers (e.g., for substance use treatment). Fidelity assessments provide a mechanism to learn more about how these and other practices enable small programs to deliver the full model. If combined with outcome data, the benefit for clients can be assessed. This work is important in Ontario, where about 45% of EPI is delivered by program sites with two or fewer clinical FTEs (

15).

An important characteristic of fidelity scales is that they articulate the core components of an intervention. The Ontario EPI program standards were released in 2011, but they were packaged in a narrative document that was not easily translated into actionable components of care. The FEPS-FS has articulated a core set of EPI model components that can guide program implementation in Ontario. However, because the scale is based on an international evidence base, it has also appropriately generated discussion about expectations for EPI practice in the Ontario system. For example, the Ontario standards include items that are not currently in the FEPS-FS, such as peer support, and the FEPS-FS includes items, such as clozapine use and supported employment delivered by a specialist, that are not currently part of the Ontario EPI standards. The rate of incident cases of persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorder served was not rated. Given the importance of assessing EPI delivery in relation to population need, the decision to not rate this item needs more discussion. Overall, a systematic assessment of the content validity of the scale for the Ontario context would be important.

Although this initial use of the FEPS-FS demonstrated its value, further validation is needed. A longitudinal study is under way in Ontario to evaluate whether implementation of coordinated specialty care improves program fidelity to the EPI model. This study will provide an opportunity to assess the predictive validity of the FEPS-FS and its sensitivity to practice change. In addition, fidelity assessments are continuing within EPION programs, and collection of common outcome data is being explored. As the cohort of assessed programs grows, narrative on the characteristics of higher- and lower-performing programs can inform discussions about whether ratings of 4 or 5 are useful indicators of satisfactory or exemplary care. If common outcome data are collected, predictive validity of the scale can be examined, including whether some components have more influence on outcomes than others. Finally, future work is planned to learn whether and how assessed programs are using the data for quality improvement.

Each program review required an average of 53 hours of assessor time (with three assessors per review), including travel. Training time was additional. Although the assessors were enthusiastic, turnover has already occurred. Sustainability strategies for this model (e.g., assessor screening and reimbursement) are being discussed, as well as the utility of less labor-intensive fidelity assessment approaches (e.g., via administrative data and telephone interviewing) (

3).

A number of study limitations should be noted. The sample was small and recruited from interested programs. The results for this early-adopter group may not reflect the broader EPI sector. As programs continue to volunteer to be assessed, a broader view of sector performance will emerge. Although efforts were made to enhance rating consistency, interrater reliability was not assessed. Use of fidelity ratings for accountability would require formal monitoring of interrater reliability. The use of 4 as a cutoff for satisfactory care was based on Addington and colleagues’ (

9) study and requires further validation. Finally, Ontario is a unique health care system, and scale validity for assessing quality of practice in other settings needs further testing. Despite these limitations, this study represents a first step in helping to build a common international framework and set of processes.

Conclusions

The FEPS-FS proved to be a useful measure for assessing the degree of EPI implementation in Ontario programs, in relation to both provincial and international standards. Adherence was satisfactory or exemplary for a number of components, but areas of challenge were also identified. Component scores showed a good spread, suggesting that the scale was able to capture variance in program quality, identify areas for improvement and provide a baseline from which to measure change. Additions to the scale are planned in order to address components of the Ontario standards that are not covered by the FEPS-FS. Building a sector improvement strategy that includes routine fidelity assessments is a larger challenge that is being explored. Beyond the Ontario context, this study reported the first use of peer raters for fidelity assessment, and the results may contribute to building a common international framework and set of processes.