It is well established that individuals with severe mental disorders have an impaired ability to work. Consequently, many of them are unemployed or completely out of the labor force. Individuals with schizophrenia or other nonaffective psychotic disorders are often already unemployed years before their first actual hospitalization (

1,

2). This pattern most likely explains the low reported employment rates among individuals with schizophrenia (i.e., the estimates range from 10% to 30%) (

3–

6). Although slightly higher rates of employment, from 40% to 60%, have been documented for individuals with bipolar disorder (

7), a recent study using national hospitalization registry from Israel found that only approximately 25% of all patients with bipolar disorder earned more than the prevailing national minimum wage (

2).

In this study, we examined employment, income, and social income transfer levels before and after a hospitalization for a serious mental disorder (i.e., schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, or bipolar disorder). To conduct a comprehensive and nationwide case-control analysis, we used Finnish longitudinal population cohort register data, which include all admissions to Finnish hospitals.

Methods

Study Population

Using unique personal identifiers, which have been allocated to all Finnish residents beginning in 1969, we linked the Hospital Discharge Register of the National Institute for Health and Welfare, the full Finnish population register (FOLK), and the Finnish Longitudinal Employer-Employee Data (FLEED) register of Statistics Finland to construct the current study population. The Hospital Discharge Register was used to identify all individuals who had been hospitalized for schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, or bipolar disorder. FOLK is constructed from administrative registers, is updated annually, and contains demographic characteristics of the whole Finnish population. FLEED is composed of comprehensive annual panel data that record the entire Finnish working-age population. It is constructed from administrative registers including information on individuals’ labor market status, salaries, and other sources of income extracted from tax and other administrative registers, such as mandatory government-run pension programs. FLEED is available from 1988 onward; for the current study, we used data from 1988 to 2015.

Participants in the Case and Control Groups

Case groups were defined by identifying all individuals who had been hospitalized for schizophrenia (ICD-10, F20), other nonaffective psychosis (ICD-10, F22–29), or bipolar disorder (ICD-10, F30–31) between 1988 and 2015 in Finland. Individuals who were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, or bipolar disorder before age 15 or after age 60 were excluded. Only data from the first such hospitalization and primary diagnoses were used, and thus an individual was categorized only into one diagnostic group (e.g., schizophrenia). Using FOLK data, we randomly selected five participants who did not have a diagnosis of a severe mental disorder as the control group for each case participant. As matching criteria, we used sex as well as birth year and month. The control participant had to be alive and live in Finland during the year when the case participant was diagnosed. Thus, the differences observed between participants in the case and control groups represent differences between individuals with a severe mental disorder and a random population-based sample. Participants in the case and control groups were followed over the same observation period.

Ethical Permission

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the National Institutes of Health and Welfare. Data were linked with the permission of the National Institutes of Health and Welfare and Statistics Finland.

Socioeconomic Measures

Annual employment status was measured as the employment status during the last week of each calendar year. Individuals who were working or self-employed were defined as employed. All others were classified as not employed. Personal income was measured annually, and the following three different measures of income were used: taxable income, earnings, and income transfer payments. Taxable income is a broad income measure. It includes annual wage and salary earnings, self-employment income, capital income (dividends and capital gains), social security benefits (e.g., parental leave and unemployment benefits), and income transfers (e.g., child allowance). Earnings were measured as the average of annual wage and salary earnings and self-employed income for each year. Income transfer payments consist of social security benefits and income transfers, including permanent and temporary pensions. To allow for the comparability of income measures over the observation period, all measures were adjusted to the base year 2015 by using the official consumer price index maintained by Statistics Finland.

Statistical Analyses

Data were constructed such that the time point zero represented the year when the first hospitalization for schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, or bipolar disorder occurred for each case participant. If an individual did not have data for a certain year, the corresponding case or control participant was not included in the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics of the proportions of individuals who were employed as well as the mean and median (rounded to the nearest 10th) earnings, income transfer payments, and total income levels were reported for three diagnostic groups (schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, and bipolar disorder) and three corresponding control groups. Differences between group means in total income were examined using nonparametric bootstrap analysis (

11) because statistical assumptions for parametric tests (i.e., normal distribution and homogeneity of variance) were violated. Stata, version 15.1, was used in all statistical analyses.

Results

Altogether, 50,551 individuals with severe mental disorders were identified during the study period. For 6,939 individuals, the first inpatient diagnosis was schizophrenia; for 34,565 individuals, the first inpatient diagnosis was other nonaffective psychosis; and for 9,047 individuals, the first inpatient diagnosis was bipolar disorder. The number of participants in the three diagnosis categories and their matched control groups per measurement year are shown in

Table 1.

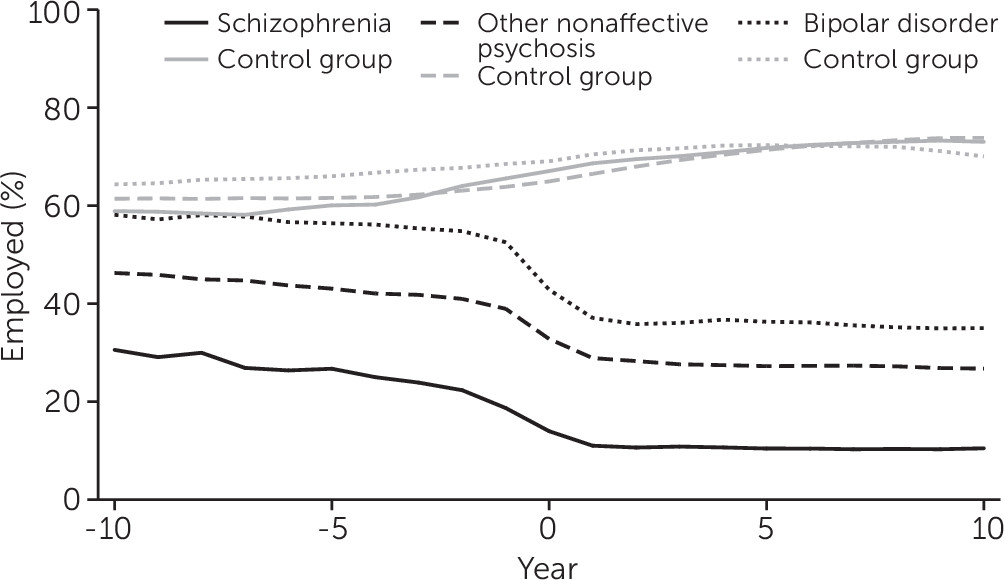

Figure 1 reports the average employment status for case and control groups. In all years, the average employment status was clearly lowest among individuals with schizophrenia and highest among individuals with bipolar disorder compared with the control groups. At the end of the year when the first inpatient diagnosis was given, on average, 14% (N=968) of individuals with schizophrenia, 33% (N=11,335) of individuals with other nonaffective psychosis, and 43% (N=3,875) of individuals with bipolar disorder were employed. In comparison, between 65% (N=112,259) and 69% (N=31,242) of the participants in the control groups were employed. There was a clear decreasing trend in the average employment status during the years before the first inpatient diagnosis was given, and after that the average employment status remained relatively stable.

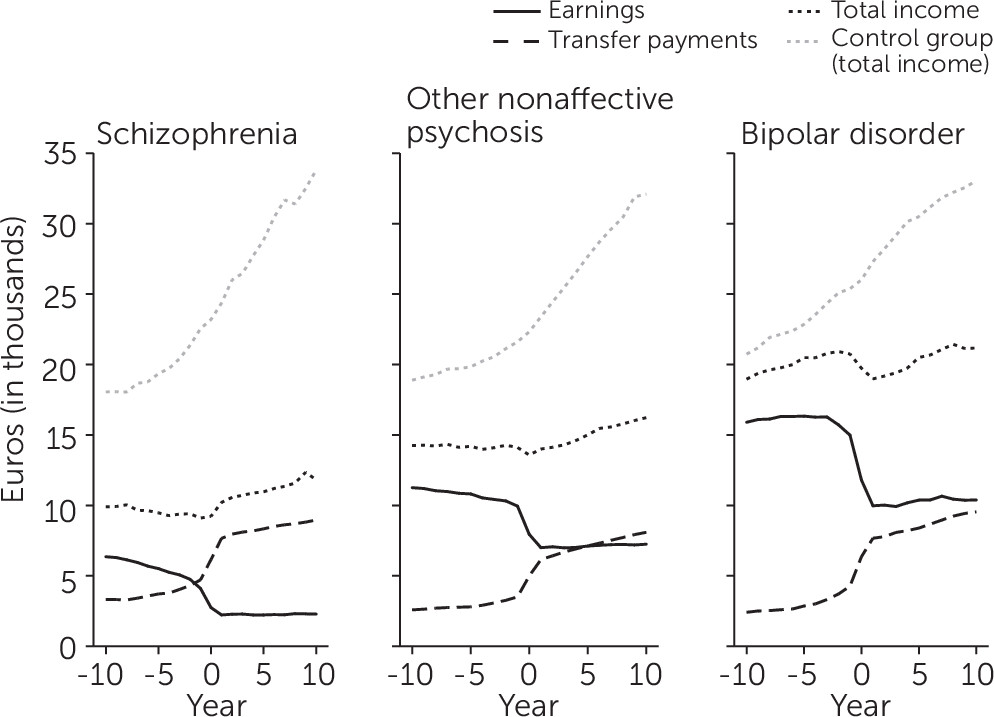

Average yearly earnings, income transfer payments, and total taxable income for participants in the case and control groups are shown in

Figure 2. The average total taxable income was approximately two times higher for individuals with bipolar disorder and around 1.5 times higher for individuals with other nonaffective psychosis compared with individuals with schizophrenia. The differences in the average total income between individuals with schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, or bipolar disorder and their matched control groups were all statistically significant (p<0.001).

The dynamics of the relationship between earnings and income transfers were rather similar in the three case groups. First, the average earnings decreased rapidly between 1 and 3 years before the diagnosis, and then the earnings remained rather stable. By contrast, the average income transfers increased during the year when the first inpatient diagnosis was given, and this increasing trend continued during the following years. On average, during the year when the first inpatient diagnosis was given, individuals with schizophrenia earned 40% of the total income earned by the control group, compared with 61% among individuals with other nonaffective psychosis and 76% among individuals with bipolar disorder. Five years later, the same proportions were 39%, 54%, and 67%, respectively; 10 years later, they were 37%, 51%, and 66%, respectively.

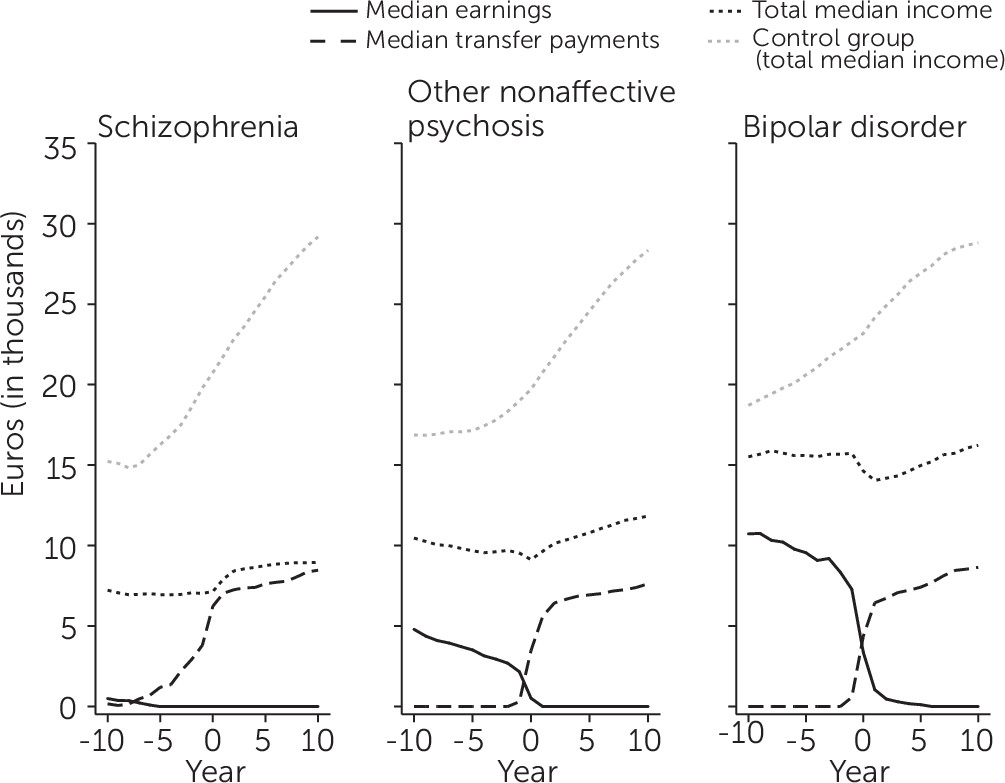

Median earnings, median social income payments, and the median total taxable income for participants in the case and control groups are shown in

Figure 3. Already years before the first inpatient diagnosis, the median earnings were zero among individuals with schizophrenia. Higher median earnings were found for individuals with other nonaffective psychosis (around 3,000 euros 3 years before diagnosis) or bipolar disorder (around 9,000 euros 3 years before diagnosis). However, in these two groups, the median earnings dropped to zero after the year when the diagnosis had been given. The median income transfers were rather equal across the three groups.

Discussion

Using comprehensive register data of individuals hospitalized with a severe mental disorder in Finland, in this study we have demonstrated that individuals with a serious mental disorder had a notably low level of participation in the labor market before and especially after their first inpatient diagnosis. There was a clear gradient between incomes of the case groups and the control groups, with disorders of greater alleged severity associated with larger income gaps; individuals with schizophrenia had 40% of the total income earned by their matched control group, compared with 61% for individuals with other nonaffective psychosis and 76% for individuals with bipolar disorder. Among individuals with schizophrenia, most of the total income consisted of income transfer payments, and in the two other groups (i.e., other nonaffective psychosis and bipolar disorder), income transfers increased consistently after the diagnosis was given.

These findings are in accordance with previous studies in which low employment rates were reported among individuals with schizophrenia (

2–

4), other nonaffective psychoses (

2), bipolar disorder (

7), or other severe mental disorders (

12). However, most of the earlier studies did not examine average income over several years or used incomplete and coarse income measures, such as the Israeli study in which at the time of the first diagnosis, 8% of patients with schizophrenia, 12% of patients with other nonaffective psychosis, and 21% of patients with bipolar disorder earned more than the prevailing national minimum wage (

2). Moreover, to our knowledge, this study is one of the first to examine the interplay between wage or salary income with a comprehensive measure of income transfer payments.

Our results show that whereas salary income decreased significantly years before the first diagnosis, income transfers increased rapidly during and after the year of the diagnosis. For individuals with schizophrenia, on average, the income transfers constituted approximately 76% of the total taxable income, and even for individuals with bipolar disorder, the share was around 40%. The reported median income transfers increased steadily after the diagnosis of a mental disorder. However, whereas more than half of individuals with other nonaffective psychosis or bipolar disorder had some earnings before the diagnosis, the median earnings were zero among individuals with other nonaffective psychosis after the diagnosis, and they also approached zero among individuals with bipolar disorder. These findings indicate that after an onset of a severe mental disorder, income transfers are the main source of income for most individuals with a severe mental disorder, and their long-term economic well-being depends largely on income transfer payments.

Although not examined in this study, there are several plausible mechanisms that likely explain why individuals with a serious mental disorder have difficulties in getting and maintaining jobs. From the psychosocial factors, for example, poor neurocognitive functioning, problems with intrapersonal or social functioning, current or residual symptoms such as paranoia or anhedonia, untypical behavior, and poor motivation are likely important (

8,

13–

15). In addition to these factors, poor educational attainment, absenteeism due to time spent in hospital care, and stigmatization further limit the possibilities of finding and maintaining stable employment (

16,

17).

Employment is often regarded as a recovery goal among individuals with a severe mental disorder. Supported employment and the individual placement and support (IPS) model have been shown to be at least two times more effective than alternative services in placing individuals with a severe mental disorder in competitive employment (

18,

19). Randomized controlled trials from Sweden (

20) and Norway (

21) have shown that even in a comprehensive welfare system with strong job security, the IPS model has achieved better results than normal care. In addition, there is some evidence that after gaining employment, individuals with a severe mental disorder have lower probability of experiencing psychiatric hospitalization (

22). Because the rate of clinical and functional recovery has not been very high among individuals with a severe mental disorder (

8), and remarkably low among individuals with schizophrenia (

10), it is important to prioritize employment models such as IPS that could enhance the opportunities for individuals with a severe mental disorder to gain stable employment.

In addition to highlighting the importance of proper intervention mechanisms, our findings emphasize the importance of predicting as early as possible whether an individual could possibly develop a serious mental disorder later in life. Targeting employment services for young adults with early-stage mental health problems could also increase the likelihood of getting them employed after an onset of a serious mental disorder (

23). This type of service would be especially important because serious mental disorders with an onset in early adulthood have been associated with low levels of employment and educational achievement over the work-life course (

24). It could also prevent young adults from falling into the “disability trap,” which refers to a situation in which a person receiving disability benefits is very rarely able to leave disability status because that would threaten his or her benefits. The avoidance of “disability trap” is a major policy concern in many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (

25). From the public policy perspective, maximizing the labor force participation of individuals with a serious mental disorder would be crucial.

The main strength of this study was the use of high-quality register data that enabled us to combine information of all hospitalizations with accurate employment and income data before and after an individual was diagnosed as having a severe mental disorder. The main limitations were also related to the use of register data, which were originally not designed for research purposes.

First, although the diagnostic validity of schizophrenia (

26) and type I bipolar disorder (

27) diagnoses has been reported to be good, the diagnostic validity of other nonaffective psychoses and type II bipolar disorder has not been evaluated. However, the diagnoses are often based on clinical observations made during a hospitalization of several weeks, and in typical cases, several diagnostic procedures have been used by a number of psychiatrists, which likely increase the reliability of the diagnoses.

Second, this study included only individuals who were treated in a hospital because of their mental disorder. Individuals who received treatment in primary care or in outpatient clinics, or who did not seek treatment at all, were not included. Thus, our findings may not be applicable to less severe or better-managed serious mental disorders.

Last, our findings, which relate to the dynamics of the relationship between earnings and income transfers, are likely generalizable only to institutional settings where similar welfare systems and income transfer payments exist. Although similar disability policy reforms, ranging from passive income maintenance to active employment encouragement, have been recently conducted in most OECD countries (

28), the diversity in disability policies between countries remains substantial (

29).