Inpatient psychiatric hospital services as they currently exist have little to no evidence base, and research has not clearly shown that hospitalization is more effective than alternative treatment methods (

1). There is evidence that endorsement of suicidal and violent ideation decreases with hospitalization, but it is unclear whether this is simply the natural course of these impulses, whether hospitalization specifically mediates this outcome, or if other primary driving factor are at play (

2).

Heterogeneity is the norm across the United States, and wide differences in inpatient psychiatric practices exist between states as well as within states. There is no professional consensus on best practice for unit treatment programming, outcome measures are not consistently used, and protocols for adaptation of evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions to the inpatient setting have been neither widely researched nor adequately disseminated. Furthermore, the impact of inpatient length of stay on outcome is largely unexplored at the patient level, existing data are not diagnosis specific, and site of care (for example, an academic medical center, rural community hospital, or for-profit system) dramatically affects lengths of stay, interventions received, and care experiences for both patients and their families.

A number of concerns are present and widely acknowledged in the field. For example, admission criteria for hospitalization are primarily guided by legal hold criteria, liability concerns, and insurance algorithms rather than by optimal care needs. Average lengths of stay have shortened because of financial pressures of the current payment model rather than evidence-based decision making, and step-down outpatient programs (which are needed for continuity of care following inpatient admission) are few and far between. Patients with repeated emergency room presentations—a fact which alone could be considered an indicator of both severity of illness and lack of care alternatives—are often paradoxically restricted from access to inpatient care because of loss of hope that available services could be of benefit. The stark reality of this can be seen in cities across the county where many severely mentally ill patients are caught in a revolving door between emergency departments and jails (

3). A root cause analysis in a recent observational study at a top-tier academic psychiatric inpatient unit revealed that admitted patients’ top three concerns included not knowing their diagnosis, not understanding how treatment recommendations/activities offered on the unit were relevant to their specific needs or treatment trajectory, and not knowing what their next care step was or how to be discharged (unpublished data, Clarke A, Sanborn K, Foad S, 2018).

Coming face-to-face with the shortcomings of the prevailing approach to inpatient mental health care and the resultant overwhelming lack of patient satisfaction across institutions, we posit that the entire approach to inpatient hospitalization is in need of a fresh approach.

A New Model: What Needs to Happen to Achieve Continuous, Integrative Behavioral Health Care

In an Open Forum previously published in this journal, Glick and colleagues (

4) focused on the need to reform inpatient psychiatric care and outlined a model based on “rapid formulation of diagnosis, goals, and treatment.” The model articulated three phases—assessment, implementation, and resolution—and detailed the associated requisite changes in staffing and system structure. Unfortunately, in the absence of adequate funding, among other issues, very few changes have occurred to the state of the prevailing treatment model of inpatient behavioral health care in the United States.

Deficits in the current system represent a critical missed opportunity to improve patients’ lives and, to rise to this calling, we believe the modern inpatient model must make a fundamental shift in the way it thinks about its patients and itself. A clear need has emerged for a new vision for the 21

st-century acute inpatient psychiatric hospital that is evidence-based and that incorporates distinct, measurable goals tied to a comprehensive treatment plan tailored to address a patient’s lifetime course of illness. A systematic, measurement-based protocol would not only ensure quality of care but also would allow for rigorous testing of numerous aspects of hospital-based mental health care. As such, we strongly agree with similar approaches to structural revision of psychiatric hospitalization, such as the recently outlined “333” model of acute mental health care delivery (

5).

What Needs to Happen in Hospitals to Achieve Continuous, Integrative Behavioral Health Care

We take the view that a patient’s admission to an inpatient psychiatric unit is and must be treated as a sentinel event signaling the need for generation of a robust action plan and initiating a cascade of collaboration across the care continuum and social continuum. This moment of de facto severity calls us to help change the course of patients’ illness by intervening not only as individual healers, but as system thinkers. Similar to medical-surgical units, which serve limited but important functions, inpatient units must embrace and emphasize their unique capabilities as a specific and targeted contributor to a larger continuous system of care in the community, not as a catch-all setting for a failed continuum.

Currently, despite the expense of inpatient hospitalization, the precise role that it should play has yet to be cohesively defended. Though the setting provides the ability to implement aggressive interventions while closely interacting with and monitoring patients 24 hours a day, several domains of intervention that could highly benefit admitted patients remain underutilized in the course of a standard inpatient stay today. In order to leverage the strengths of an inpatient stay, we believe that the stay should be a supportive yet immersive experience built on intensive, structured interventions matched to a clearly articulated list of requisite goals. Such goals should principally involve meeting the patients’ needs for safety, diagnostic clarification, psychoeducation, treatment planning, detailed connection and collaboration with subsequent levels of care, and initiation of treatment for acute needs until transition can safely occur. Successful delivery of each of these domains during an inpatient stay will require an intentionally designed and highly choreographed experience for both patient and treatment team. Facilitation of this process would be greatly enhanced through the use of mental health–specific measurement and planning tools usable by both patients and their care team.

With goals of inpatient hospitalization agreed upon, each institution could then begin to establish processes by which those goals can be achieved on a given inpatient unit during the course of an admitted patient’s stay. Delineating these roles for the acute inpatient unit will allow clinicians, researchers, and payers to more adequately identify which patients will benefit most from which services and when and could lead to the development of a relevant set of level-of-care admission criteria based on the given setting’s strengths and limitations, patient characteristics, and services.

Phases of Psychiatry Hospitalization and Goals of Care: The S.E.T.U.P. Model

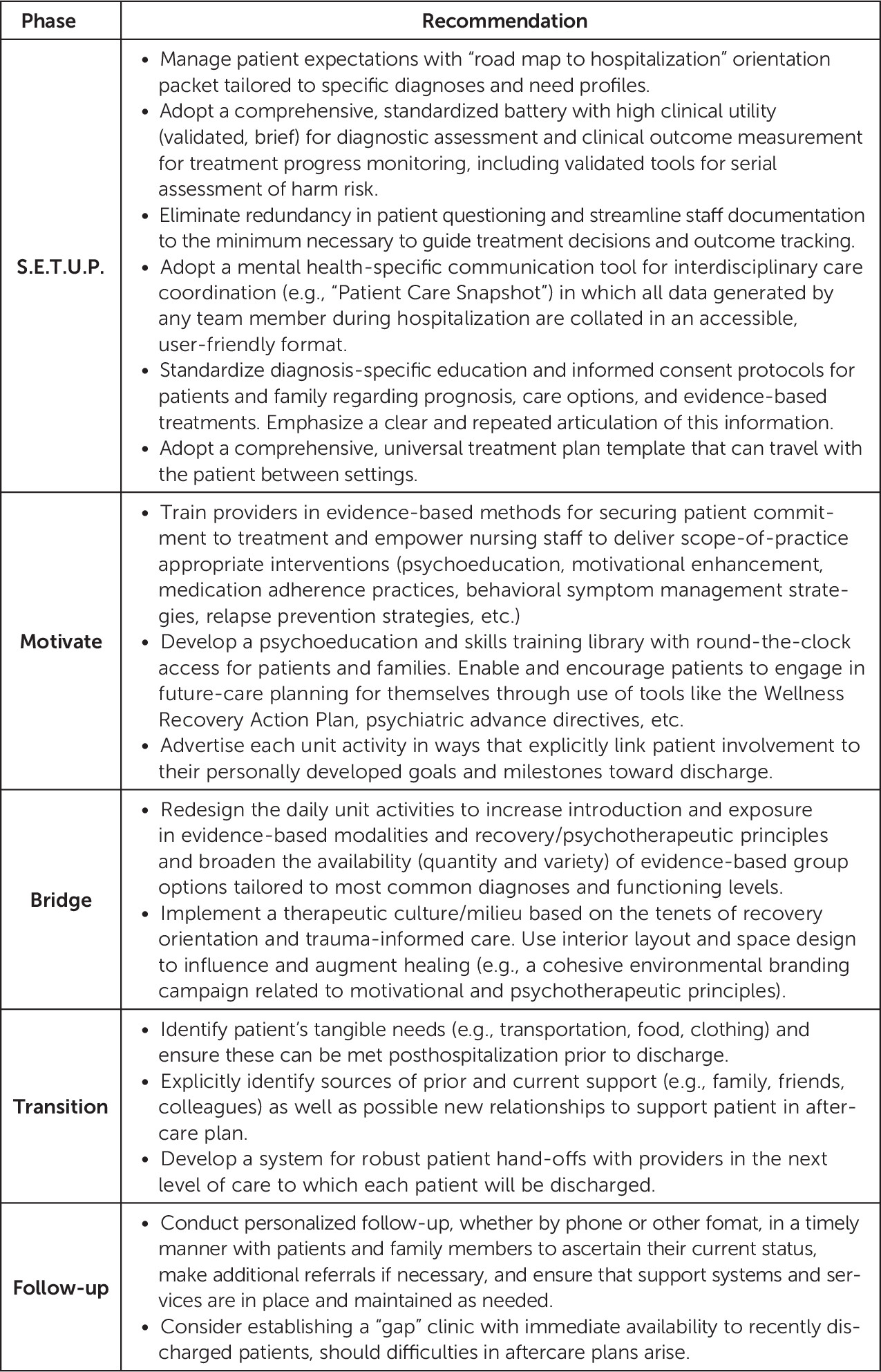

Hospitalization should aim to change the trajectory of the patient’s illness, and an explicit understanding of what led to the need for hospitalization must be uncovered and linked with what must change to mitigate the risk of rehospitalization. Based on its specific role in a patient’s care lifecycle, the inpatient setting is uniquely positioned to meet four key needs: setting the patient up for success, motivating the patient to engage in care now and going forward, providing bridging treatment, and ensuring successful transition to follow-up care. To move the field forward, we describe a new model for inpatient practices aimed at organizing the inpatient experience around these needs and integrating inpatient and outpatient care planning and delivery. Key elements of the model include evidence-based care of the acutely ill patient and an integrated treatment plan that follows the patient throughout various levels of care.

Named after its first steps, the S.E.T.U.P. model is structured to refocus the emphasis of inpatient psychiatric care. The proposed structure lays the groundwork for a standardized inpatient psychiatric hospitalization protocol for which a specific measurement-based platform could be built and studied for efficacy. An electronic tool to guide evaluation, patient measurement (including patient-centered goals, care-relevant metrics, and longitudinal outcome tracking), clinical decision making, care team coordination, and disposition planning has the potential to contribute dramatically to the field.

S.E.T.U.P.

Stabilization.

All intervention for psychiatric crisis must begin with stabilization for safety and adequate evaluation to be possible. Traditionally, this has been the strength of inpatient psychiatric care, but we recommend a significant strengthening in intensity of other care domains.

Evaluation.

Diagnostic evaluation follows stabilization in order to determine care needs (symptoms, diagnosis, functional impairments, clinical and psychosocial needs) and identify future level and scope of the treatment/services and referrals that are required. Incorrect diagnoses often end up being carried forward, leading to ineffective treatments. Comprehensive diagnostic formulation should be prioritized, and we recommend standardized evaluation, measurement, and progress tracking with validated clinical tools and scales that consider acute symptoms in the context of the patient’s chronic illness history and establish a baseline clinical snapshot and are repeated regularly to track response to interventions. Psychiatrically, evaluations should emphasize formulations inclusive of several conceptual lenses (biological, psychological, behavioral, social, cultural, etc.). Medically, the inpatient setting has the capacity to play a major role in reversing the vast amount of undiagnosed and untreated physical illness among patients with mental illness by emphasizing diagnosis, treatment initiation, and connection to outpatient follow-up (

6).

Teaching.

Because the patient and/or their significant others should be considered the most important members of the treatment team, teaching (or psychoeducation) is given its own step in the model; not only is the patient the primary decision maker, but ultimately she or he must act as the quarterback in carrying out all treatment recommendations. Rather than feeling “in the driver’s seat,” many patients currently find themselves feeling uninformed, confused, and without a guide at discharge. Given that patient knowledge is the cornerstone of collaborative goal setting and shared decision-making, teaching should be robust and systematized.

Universal planning.

In addition to identifying and addressing immediately solvable problems, a universal treatment plan should focus on function, independence, and quality of life and aim to address nonurgent, more complex problems with efforts initiated during the hospitalization and further carried out in outpatient settings. Because emotional, physical, and psychosocial needs are functionally linked and can significantly affect one’s ability to achieve a successful treatment outcome, a true treatment plan should be a comprehensive, integrated plan, not just for a given hospitalization but for a broader course of illness and life cycle of treatment.

Motivate

Durable treatment planning is predicated on the formation of a strong alliance between treatment team and patient, and patients’ autonomy and agency are paramount. Without addressing patient resistances, the likelihood that plans will function beyond a given setting is limited at best, so all planning should include a heavy emphasis on agenda setting and motivational assessment/enhancement.

Bridge

Beyond stabilization and treatment planning, all hospital-based psychiatric treatment should be considered bridging treatment. While focus should be ameliorating the symptoms responsible for this specific hospitalization, bridging care must also ensure that successful transition to continuation of care is available in subsequent settings.

Transition

A visible care continuum can be very containing for a patient struggling with mental illness, and we feel that establishing a strong connection and collaboration with the follow-up care settings is a critical change for improving patient outcomes. As the highest level of care, inpatient mental health must begin to serve as a supportive and integrated entry point to a containing, collaborative continuum of care, both psychiatric and medical. Teams must make a special effort to explore and elucidate barriers to obtaining subsequent care and thoroughly address these prior to transition. A smooth hand-off between care stations in the care continuum is central, including communication of a comprehensive treatment plan and discussion of nuances with the subsequent providers. Support and guidance should be provided to providers in the subsequent level of care, and while the patient is hospitalized, work should begin to strengthen his or her connection to his or her social support network and/or social programs, which can support individual’s continued engagement in treatment after hospital discharge (

7).

Follow-up

Follow-up should be as personalized as possible, aimed at directly connecting with patient and significant others when possible, including contact by the discharging unit, meetings with case manager, or visits by a mobile crisis team (

8,

9). We see a role for a “gap” clinic, specifically designed to assist with the care transition process, which can receive patients within the first visit within a few days of discharge to help coordinate care transition, aid in troubleshooting difficulties that have arisen, and keep patients engaged in the plan generated during hospitalization.

Implications of the New Approach

We anticipate several beneficial impacts of implementing these recommended changes, including increased patient engagement, knowledge, and empowerment with decreased confusion; reduction in diagnostic oversights or errors; enhanced treatment team coordination; improved consistency in delivery of quality patient experience across providers and care teams; reduced burnout from decreased documentation burden and more available time with patients leading to increased retention of experienced staff; improved assessment of treatment efficacy; facilitation of treatment and services research; and increased continuity of patient care plan, treatment delivery, and outcomes between settings and providers with related reductions in “loss to follow-up” or rehospitalization. Particular design thinking and attention should be paid to each of these five steps to improve adoption and ultimately patient outcomes. We recommend that inpatient services implement the changes listed in

Figure 1.

This comprehensive structure makes psychiatric hospitalization a more specific and directed experience. First, the new approach requires easier access to a comprehensive review of patients’ past diagnostic evaluations and treatments. This comprehensive review would be accomplished most easily with a documentation and tracking tool that the patient is able to keep and that could be accessed across care settings. The development of new tools for making the electronic medical record accessible and usable by both patients and providers can facilitate increased access to longitudinal information.

Second, a strong team practice with close coordination between multidisciplinary personnel is essential. As a result, increased staffing or changes in staffing roles with adequate resources and experience to succeed in these tasks will be required. To operate effectively and efficiently, this model may include unit administrators who have inpatient and outpatient and financial expertise, physicians and nurses with experience in treating the very impaired population most frequently hospitalized, and social workers with advanced experience and skill in facilitating communications and coordination between patients, families or significant others, and other mental health providers and amongst diverse systems of care. Third, aligning process procedures with these new hospitalization goals will require a systematic integration of both organizational and functional changes—not only within the inpatient units but also in how they connect to all levels of outpatient services (

10). A significant increase in detailed communication with and collaboration with outpatient providers and programs will be required. A comprehensive database of outpatient programs and resources available after discharge to patients and partnerships with key programs to facilitate discharge planning must be developed.

Because for many settings, implementation may require significant changes, resistance is to be expected. The financial incentives of the current system do not facilitate significant shifts in system changes and hospital administrators often argue, “Why change our approach if we are getting by as is?” A lack of appropriate, outcome-relevant measures—such as measures for symptom burden, functioning, care engagement, and quality of life—continues to inhibit clinicians’ ability to effectively assess care quality or advocate for change. We are also reminded that for every acute psychiatric hospital seeking to provide top-quality patient care, there is an urgent need to replace underfunded, inadequate continuums of care with truly integrated care continuums.

Fortunately, this model of inpatient reorganization and documentation will justify services in the new financial realities, such as alternative funding plans, the Affordable Care Act, implementation of assisted outpatient treatment regimens, a bundled-payment system, or a volume-driven pricing adjustment system. This evidence-based approach will generate an ongoing database of information to effectively reorganize inpatient psychiatric care within the context of the larger health care system without losing benefit to patients. The exploration of these and additional innovations would substantially improve the utility and value of inpatient psychiatric care (

11–

15) and has the potential to vastly improve patient experience and healing in their journey for mental health care, though all of this hinges on recognition of the need for tightly defined goals for inpatient care and for effective evaluation and measurement of symptom burden, treatment progress, and clinical outcomes.