Sites, Participant Selection, and Treatment Allocation

We conducted our study from 2015 to 2018 at three midwestern U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers and two of their associated outpatient clinics. The study received VA institutional review board approval from all three centers. We identified participants with a new diagnosis of depression and current depression symptoms by querying the electronic medical records database each week to return all patients diagnosed as having depression at a primary care encounter who had not received a depression diagnosis (in any VA setting) or specialty mental health treatment in the prior 4 months and did not have any diagnosis of bipolar disorder, primary psychotic disorder, or dementia in the prior 12 months. From this sample, we manually confirmed primary care documentation of active depression symptoms and excluded those with referrals to specialty mental health care and those who were receiving substance use disorder treatment. Individuals in the resulting sample were then screened by phone, and those eligible for the study had a score of ≥10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9), had basic skills for Internet and computer use (e.g., e-mail and online banking or shopping), and had no specialty mental health treatment outside the VA in the prior 4 months (

15). Receipt of integrated primary care mental health treatment was not exclusionary.

Participants were randomly assigned by using a minimization algorithm designed to balance the two study arms with respect to number of participants, study site, participant gender, age ≥55, use of antidepressant medication, and initial PHQ-9 score of ≥15 (

16).

Interventions

PS-cCBT participants continued to receive their usual primary or integrated care, which could include antidepressant medications or in-person psychotherapy. In addition, PS-cCBT participants received access to the online cCBT program Beating the Blues (BtB) for 3 months. BtB consists of eight CBT modules for depression and anxiety and includes video vignettes of program users, interactive assignments, and symptom self-monitoring with the PHQ-9.

Participants in the PS-cCBT arm also completed an initial in-person meeting (or a phone meeting if in person was not possible) with a peer support specialist. After this meeting, peers were expected to conduct approximately weekly phone calls and occasional in-person visits with participants to discuss progress and barriers to completing cCBT modules and to provide general peer support for managing depression. The peer specialists training consisted of a week-long certification training through the State of Michigan; the BtB program; and a 1-day study-specific training that addressed sharing one’s story related to depression, principles of motivational interviewing, and protocols for managing suicide risk. Peer specialists received weekly supervision by a clinical psychologist with prior experience supervising peers and had a peer-led monthly group consultation call (

17).

Participants randomly assigned to EUC received

The Depression Helpbook, a self-help depression workbook, in addition to their usual care (

18). Participants randomly assigned to PS-cCBT also received this workbook.

Measures

Our primary study outcomes included depression symptoms, general mental health status, quality of life, and mental health recovery. Participants completed measures at baseline and at 3 months and 6 months postrandomization. Measures were collected by using Web-based surveys that participants self-administered via a tablet or through an e-mail link to the survey. In rare cases, the measures were administered verbally over the phone or by mailing hard copies. Study staff were not blinded to study arm. For each of the primary and secondary measures described below, higher scores indicate greater levels of the measured construct.

We measured depression symptoms with the Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology–Self Report (QIDS-SR) (possible scores range from 0 to 27) (

19,

20) and general mental health status with the mental health component subscale (MCS) of the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12) (

21,

22) (scores are standardized to a mean of 50). We measured quality of life by using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (Q-LES-Q-SF) (possible scores range from 14 to 70) (

23) and recovery by using the Recovery Assessment Scale Short Form (RAS-SF) (possible scores range from 20 to 100) (

24).

Secondary outcomes included CBT skills, which were measured by the 16-item Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Skills Questionnaire (CBTSQ) (

25) (possible scores range from 16 to 80). Anxiety was measured with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder seven-item scale (GAD-7) (

26) (possible scores range from 0 to 21). Hope was measured with the six-item State Hope Scale (SHS) (

27) (possible scores range from 6 to 48).

We measured usual care treatment from baseline to 6 months by using electronic medical records, examining any antidepressant medication prescription. Among antidepressant users, we measured antidepressant medication possession ratios (MPRs), which were defined as the number of days of antidepressant medication on hand divided by the 6-month observation period. We also measured receipt of any psychotherapy and number of psychotherapy sessions completed among psychotherapy recipients.

Patient characteristics measured at baseline via survey items included age, gender, race-ethnicity, marital status, income, education, employment, number of lifetime depressive episodes, age at first onset of depression, social support (via the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List [

28]), and physical health (via the physical component subscale of the RAND VR-12) (

21).

Participation in BtB was measured by the number of modules completed from the administrative dashboard of the computer program. The number of peer sessions completed was measured by peer documentation in participants’ medical records.

Analyses

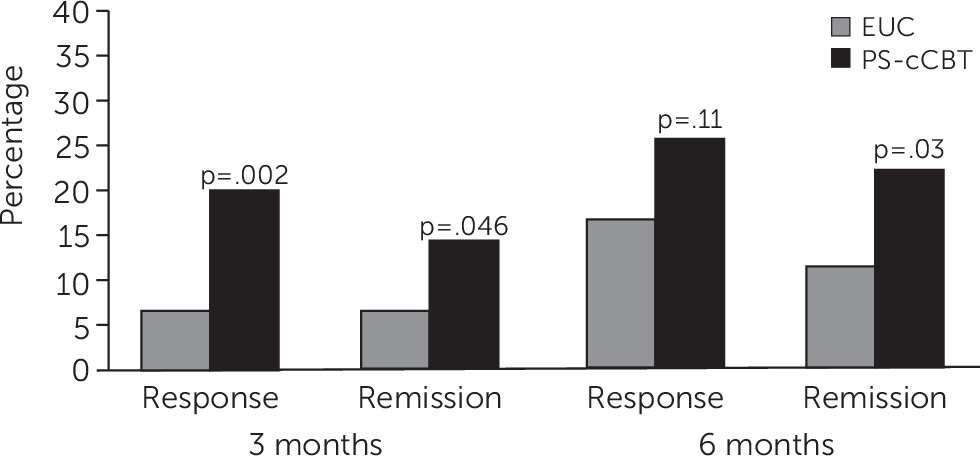

To assess balance between treatment arms, we evaluated participants’ baseline characteristics, including the primary outcomes, by arm. We used an intent-to-treat approach and included all participants in their randomly assigned group, regardless of patient adherence to the intervention components. We conducted unadjusted comparisons between treatment arms for the primary and secondary outcomes at 3 and 6 months. We also dichotomized depression symptom improvement as both response, defined as a 50% reduction in QIDS-SR score from baseline to follow-up, and remission, defined as a QIDS-SR score of ≤5 at follow-up. We then compared response and remission rates by arm at 3 and 6 months by using chi-square tests and calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) for significant differences (

29).

Our analytic goal was to estimate intervention effects at 3 and 6 months. For the primary outcomes, main analyses consisted of longitudinal linear mixed-effects models with the outcomes data at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months as response variables and with participants as random intercepts. For each outcome model, primary predictors were treatment arm, treatment site, and categorical indicators for 3 and 6 months. We used interaction terms of study arm × 3-month time and study arm × 6-month time to estimate the between-group mean differences at 3 and at 6 months, respectively. The following baseline characteristics found to be associated with follow-up completion or depression at 3 months were also included as covariates: gender, race-ethnicity, education, social support, physical health, lifetime number of depressive episodes, and age at first onset of depression.

For participants assigned to the intervention arm, we used simple regression models to assess whether number of peer specialist encounters or number of BtB modules completed predicted improvement in the primary outcomes at 3 and 6 months. We similarly evaluated the association between peer encounters and cCBT modules completed and the association between cCBT modules completed and CBT skills at 3 and 6 months. We also compared primary outcomes among those who completed five or more cCBT modules (our threshold for adequate treatment) versus those who completed fewer than five. Analyses used SAS software, version 9.4, and SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.15.