Despite growth in the use of telemedicine (

1) for treating mental and substance use disorders in rural areas, studies of associated improvement in access to treatment are limited to coverage by private insurance or Medicare. Medicaid is the primary payer for mental health services in the United States and covers more than one-fifth of substance use disorder spending (

2). In addition, Medicaid beneficiaries use telemedicine primarily for behavioral health disorders (

3). However, studies have not addressed whether telemedicine expands access to behavioral health care for Medicaid beneficiaries in rural areas, compared with nonrural areas.

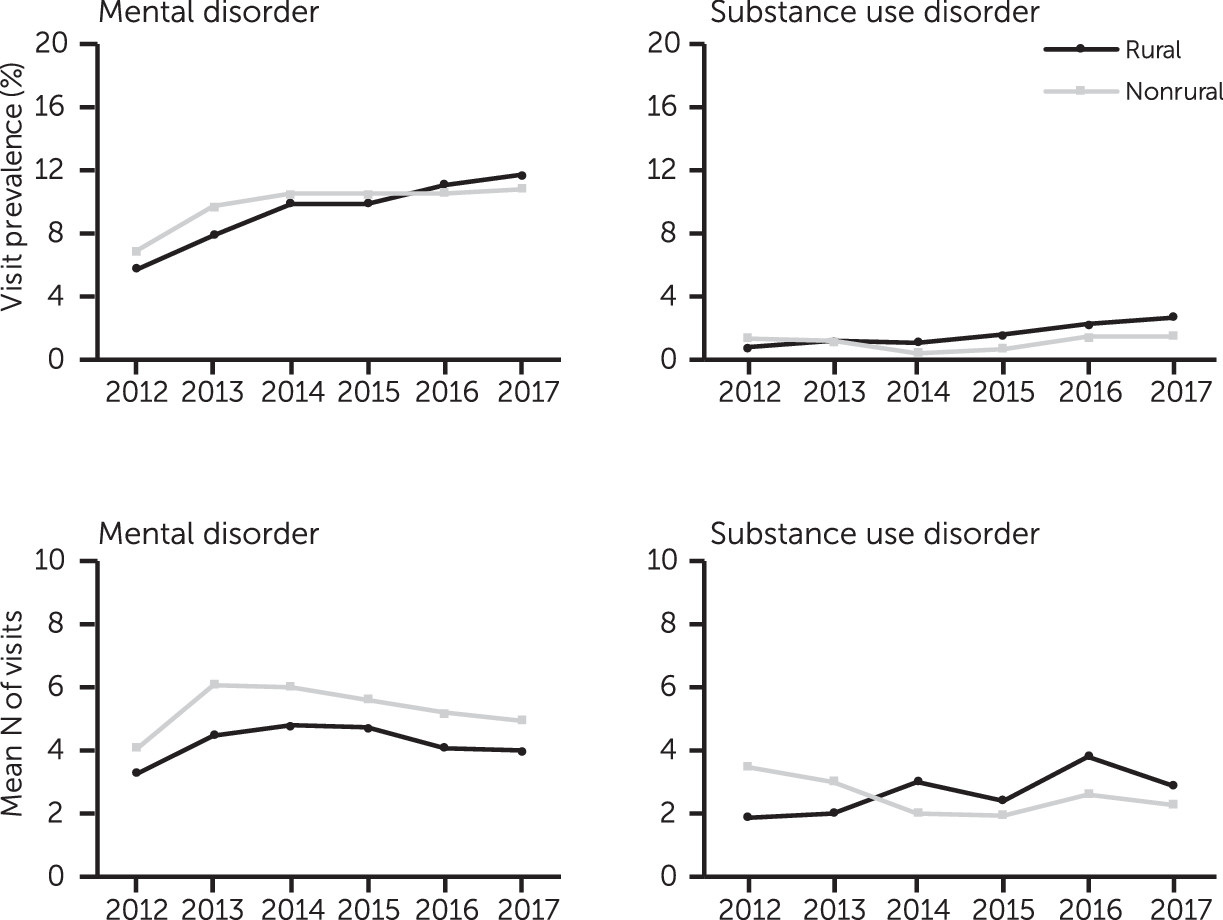

In this study, we examined the prevalence and amount of mental and substance use disorder telemedicine use among Medicaid beneficiaries as reflected by 2012–2017 claims data. We also assessed whether patterns of telemedicine use varied between rural and nonrural areas and by diagnosis.

Methods

Data

We analyzed 2012–2017 claims data from the IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database, which contains deidentified claims from millions of Medicaid beneficiaries in geographically diverse states. We limited our analysis to states that continuously contributed data throughout the study period. Data use agreements preclude identification of the states. We restricted our analysis to beneficiaries ages 18–64 years who were not enrolled in Medicare, had a Medicaid plan that included mental and substance use disorder and pharmacy coverage, were continuously enrolled in Medicaid for at least 1 full calendar year during the study period, and had at least one claim with a primary mental or substance use disorder diagnosis. We identified diagnoses by using ICD-9 codes (codes 290–316) and ICD-10 codes (codes F01–F99). We used ICD-9 codes for 2012–2014 and the first three quarters of 2015 and ICD-10 codes for the last quarter of 2015 and 2016–2017. (A table listing the codes is included in an online supplement to this article.)

We excluded states with no Medicaid telemedicine claims for mental and substance use disorders during the study period. The unit of analysis was the beneficiary-year, and each unique beneficiary could contribute multiple beneficiary-years to the sample. Our final analytic sample of beneficiaries with primary mental disorder diagnoses was 2,654,339 beneficiary-years from 1,335,138 unique beneficiaries. The final analytic sample of beneficiaries with primary substance use disorder diagnoses was 663,068 beneficiary-years from 420,305 unique beneficiaries. Because some beneficiaries had both mental and substance use disorders, the total sample was 1,603,066 unique beneficiaries contributing 2,986,100 beneficiary-years of data.

Behavioral Health Telemedicine and Outpatient Visits

We measured telemedicine claims and in-person outpatient claims with a primary diagnosis of a mental disorder and, separately, with a primary diagnosis of a substance use disorder. We used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services definition of telemedicine for Medicaid policy. The definition specifies that telemedicine involves real-time communication between the patient and a provider at a distant site using interactive telecommunications equipment with audio and video capabilities. This excluded telephone, e-mail, online portal, and other electronic services. We included telemedicine sessions that occurred in outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department settings.

We created two types of outcome measures—a binary indicator of any mental or substance use disorder telemedicine (or outpatient) treatment and a continuous indicator of the number of such visits. To address skewness caused by outliers at the high end of the visit distribution, we used a maximum value of 52 (i.e., an average of one visit per week), a value above the 99th percentile.

Beneficiary Characteristics

We defined beneficiaries as residing in rural or nonrural areas on the basis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s metropolitan statistical area (MSA) associated with their five-digit zip code (

11). We classified beneficiaries who did not live in an MSA as rural and those who lived in an MSA as nonrural.

Other beneficiary characteristics examined included age, sex, race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), Medicaid health plan type (fee for service or managed care), year in which the beneficiary-year was observed, and number of years that the beneficiary was continuously enrolled in Medicaid (number of beneficiary-years). For mental disorders, we identified attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (schizophrenia), posttraumatic stress disorder, and other mental disorders. For substance use disorders, we identified alcohol use disorder, opioid use disorder, and others.

Statistical Analysis

We compared unadjusted rural and nonrural trends in the prevalence and mean number of mental and substance use disorder telemedicine visits per beneficiary-year. We made unadjusted comparisons between rural and nonrural beneficiaries on beneficiary-level characteristics. Next, we used multivariate regression models to estimate adjusted rural-nonrural differences in the prevalence and amount of mental and substance use disorder telemedicine received per beneficiary-year, controlling for all other characteristics. To test whether there were differences by diagnosis in telemedicine utilization and whether the variation depended on rurality, we extended these models with interaction terms between mental and substance use disorder diagnosis and rurality. We used an interaction between rurality and receipt of any mental and substance use disorder telemedicine to test whether telemedicine use was associated with more or less outpatient treatment and whether that relationship varied by rurality.

For models of the prevalence of telemedicine or outpatient visits, we used logistic regression. For models of the number of such visits, we used generalized linear models with gamma distributions and log links. To aid interpretation, we present the primary estimates of interest from the regression analyses as predictive margins and contrasts (

12–

14) (see

online supplement for the full output for each model).

In all stages of the analysis, we used listwise deletion to address missing values and clustered standard errors to account for the sampling of multiple beneficiary-years from unique beneficiaries.

The MarketScan data used in this study were statistically deidentified and have been certified to satisfy the applicable conditions of HIPAA. Thus this study was exempt from Department of Health and Human Services regulations requiring institutional review board approval, and patient consent was not required.

Discussion

In this study of 2012–17 Medicaid claims data, we found low overall telemedicine use for behavioral health treatment among rural and nonrural beneficiaries alike. Telemedicine use for substance use disorder services was particularly low, consistent with recent findings for Medicare beneficiaries and commercially insured individuals (

9,

15). Over the study period, the prevalence of telemedicine visits for mental disorder treatment increased more than for substance use disorder treatment, especially in rural areas. In contrast, we found that among rural beneficiaries receiving any telemedicine treatment for mental or substance use disorders, the amount of telemedicine visits for substance use disorder treatment increased more than for mental disorders. Although we cannot infer a causal relationship, this finding could reflect a response to increasing need for opioid use disorder treatment amid the opioid crisis (

16).

We also found that after adjustment for individual characteristics, rural Medicaid beneficiaries with diagnoses of behavioral health disorders were more likely than nonrural beneficiaries to receive telemedicine treatment for those disorders. This result was consistent with recently published findings on behavioral health telemedicine treatment in other samples of Medicaid beneficiaries (

3), Medicare beneficiaries (

8,

9), and commercial insurance enrollees (

15). In addition, in our study, the average number of behavioral health telemedicine visits among those receiving any visits was higher for rural than for nonrural beneficiaries.

Our findings complement a 2018 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) report on a broader set of telehealth services for all health conditions, in which receipt of telehealth services for all causes was more common for urban than for rural individuals (

17). The USDA study relied on 2015 census data, and the sample was not limited to Medicaid patients. Our results demonstrate that Medicaid populations with behavioral health treatment needs have unique telemedicine utilization patterns and emphasize the importance of considering differences in specific patterns across rural and nonrural populations.

Given overall higher rates of unmet need for behavioral health services and lack of behavioral health provider capacity in rural areas (

5), we might expect to see greater uptake and a larger rural-nonrural difference in use of behavioral health telemedicine. However, issues related to insufficient infrastructure supporting telemedicine in rural areas, as well as patient and provider attitudes toward telemedicine use, may need to be addressed to expand telemedicine availability for rural beneficiaries (

18–

20). The growth of behavioral health telemedicine in rural settings also may be affected by disparities in provider reimbursement rates, the extent to which behavioral health providers accept insurance, the extent to which substance use disorder treatment is financed with block grants and other public funding sources, and broadband–high-capacity Internet access (

21–

24). In addition, although many patients seem open to using telemedicine, some may face bandwidth or other technological barriers or simply prefer in-person visits (

25,

26).

Our findings suggest that there is opportunity to broaden the use of telemedicine, but further research is needed to support specific policy implications. Of particular interest may be future research on the use of waivers to convert Medicaid funding to block grants and how these block grants may affect the use of telemedicine. Finally, additional research is needed on how specific populations can best utilize telemedicine services, including individuals excluded from this study because of noncontinuous Medicaid enrollment.

We observed the greatest difference between rural and nonrural beneficiaries in amount of telemedicine for opioid use disorder (versus telemedicine for alcohol use disorder), with rural beneficiaries having more telemedicine visits on average. Telemedicine for medication-assisted treatment has been shown to be effective (

6) but underutilized (

3). These findings suggest possible inroads for opioid use disorder telemedicine in rural areas. However, providers may be apprehensive about prescribing because of the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which requires providers to conduct an in-person visit before prescribing a controlled substance, such as buprenorphine. Recent Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) guidance, however, exempts practitioners from this requirement if the practitioner is engaged in telemedicine and meets specific DEA requirements (

27). The 2018 SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act also seeks to expand the use of telemedicine visits for substance use disorder by addressing statutory requirements for telehealth services.

Particularly in rural areas, telemedicine was associated with greater use of in-person outpatient services. This may indicate that telemedicine’s role in improving access has been limited and that people who are already engaged in in-person treatment are the most likely to receive telemedicine. Alternatively, telemedicine may help retain people in treatment and allow them to receive more in-person treatment than they would have otherwise. Given the cross-sectional design of this study, we cannot identify the causal mechanism underlying this association, but future work should investigate this relationship further to inform how telemedicine can be harnessed to best serve Medicaid beneficiaries with behavioral health treatment needs.

State Medicaid policies related to behavioral health treatment and telemedicine coverage vary, and some policies may discourage the expansion of telehealth (

10,

28). For example, some states limit the types of providers that may deliver services via telemedicine, limit locations that can be originating or distant sites, or do not reimburse originating site facility or transmission fees (

28). States with robust Medicaid telemedicine coverage also may have greater availability of behavioral health providers who accept Medicaid. Future work should consider this state-to-state variability and the extent to which other government programs provide behavioral health telemedicine (

29), possibly filling in apparent treatment gaps.

Policy makers have multiple avenues for addressing underutilization of telemedicine for providing behavioral health services. An initial step for states may be revisiting policies that limit the ability of originating sites to recoup expenses or that greatly restrict provider and location types. Policies that enhance broadband access and other infrastructure components would expand the reach of telemedicine, as would clarifying reimbursement and regulatory requirements.

This study had some limitations. Because it relied on Medicaid claims data, we did not include beneficiaries who had behavioral health conditions but who received no behavioral health treatment for which Medicaid was billed during the study period. Thus we could not estimate the prevalence of telemedicine use for behavioral health treatment among all Medicaid beneficiaries or compare beneficiaries who received and did not receive such services. These data also did not capture telephone or online portal contacts that may have occurred in addition to—and that may reinforce—in-person outpatient visits. In addition, although our large sample yielded significant results, in some instances the differences were small.

Our study period included the October 2015 transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 diagnosis coding. Therefore, our measures of mental and substance use disorders are not consistent for the whole study period, and beneficiaries added to our sample in 2016 and 2017 could be systematically different from those identified between 2012 and 2015.

Finally, our study sampled a limited subset of Medicaid programs. Although the states represented are geographically diverse, our results cannot be used to make nationally representative inferences about rural and nonrural use of telemedicine among all Medicaid beneficiaries. Furthermore, we limited the sample to those continuously enrolled for at least 1 year, which may omit a high-risk subgroup.